How this research began…

I do not consider myself an expert on the “Battle of the Bulge.” The battle is dense and eventful. But I thought I knew enough about the Ardennes offensive to elevate me above the rank of battle hound. Then I read Alex Kershaw’s “The Longest Winter” and discovered the actions of the Intelligence & Reconnaissance Platoon of the 394th Infantry. As with some of my work, this post is centered around a map of the engagement. During the course of the research, I discovered that two of the GIs (PFC Bill James of White Plains (NY) and PFC Risto Milosevich of Los Angeles (CA) were students of my alma mater, Tarleton State (Texas A&M).

A shortage of manpower in the US military at the twilight of World War II forced the army to transfer some of its best and brightest college-educated draftees who were training to become technical experts and officers to frontline units in 1944 as enlisted personnel.

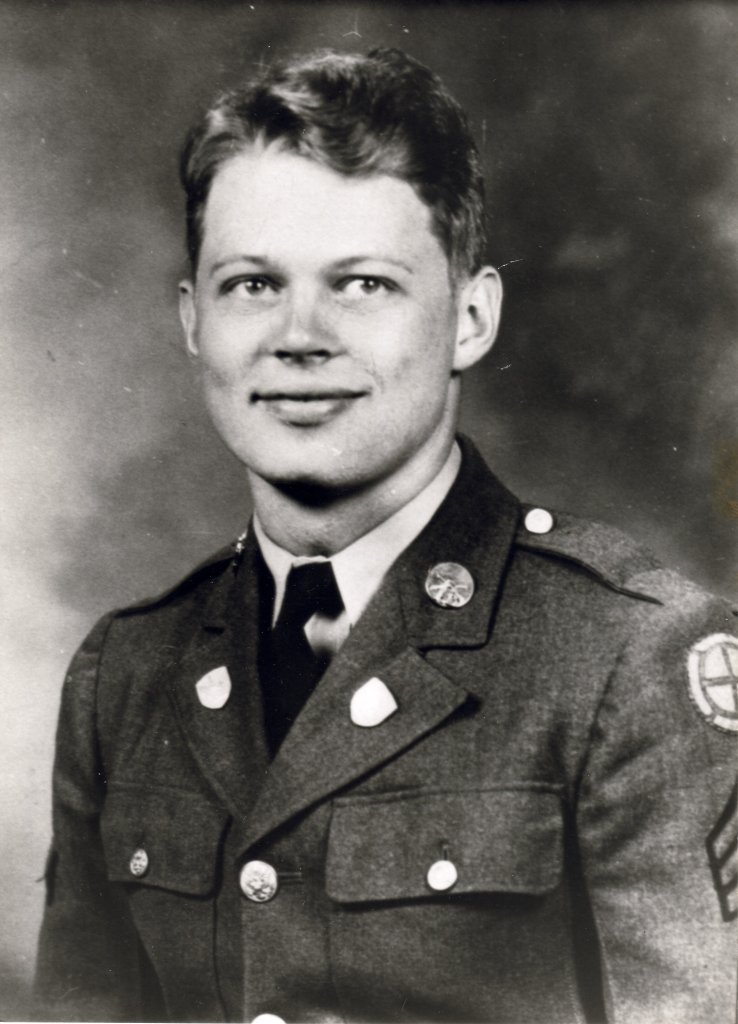

As members of the US Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), the draftees were to be employed as high-grade technicians and specialists. However, on 1 April 1944, many were reassigned to infantry, airborne, or armored units. Eighteen such men found themselves in a so-called Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon of the US 394th Infantry Regiment in the European Theater of Operations, in the winter of 1944.

Isolated, in a forward position in eastern Belgium, amid snowy, near sub-zero conditions , the platoon found itself snarled in a maelstrom of combat during the opening blows of what would become known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

Isolated Location

The 394th Infantry Regiment’s I&R Platoon had been posted to an unremarkable hilltop overlooking the Ardennes village of Lanzerath, a few thousand yards from the German frontier on 10 December 1944. Like in the rest of the Ardennes Forest, the platoon’s deployment was regarded as being in a “quiet sector” with scant presence of the hostile German military.

The core role of I&R Platoons in the US Army was to gather detailed information about enemy forces and the terrain in locations that US Arm rifle companies and battalions could not easily access. But in being posted to Lanzerath, the 394th’s I&R Platoon was also expected to fulfill another, more critical role: plugging a gap in the US lines.

The platoon’s parent unit, the US 99th Infantry Division, was a rookie to the wilds of the western European campaign. Known later as the “Battle Babies”, the division arrived on the continent on 6 November 1944, having missed the Normandy campaign and the subsequent Allied breakout across France. Posted to the Ardennes, the division’s inexperience was exacerbated by the fact that it was forced to string its three infantry regiments (393rd, 394th and 395th) out across a 25-mile front, along forest-covered hills.

US army doctrine stipulated that a infantry battalion could cover 800 yards of a frontline. But the 99th’s nine infantry battalions were each covering between 830-1,000 yards. This made it near impossible for US patrols to cover the gaps.

By 14 November, all of the 99th’s battalions and companies were on the frontline barring the 3d Battalion of the 394th Infantry, which was held in a divisional reserve near the boundary with US V and VIII Corps, near the so-called “Losheim gap”, a particularly thinly held part of the frontline.

With only two battalions under his command, Colonel Don Riley of the 394th Infantry Regiment, tried to plug potential holes in his perimeter with small units. One worry was the village of Lanzerath which commanded a road leading westwards, deeper into American lines. The village was the responsibility of the neighboring US Army units such as VIII Corps and the US 14th Cavalry Group.

However, the 394th Infantry lacked combat troops to occupy the village in force and so Riley employed the I&R platoon to provide advanced warning of a German advance or attack in the area. In command of the 394th’s I&R Platoon was First Lieutenant Lyle Bouck Jr, just 20 years old but not an ASTPer. Instead, he was a pre-war army volunteer who had risen through the ranks to become an officer.

“Our I&R Platoon was ‘temporarily’ moved into the resulting gap with orders to investigate and report any observed enemy activity,” a former platoon member, Private G Vernon Leopold, told US Congress in 1981.

The platoon’s location at Lanzerath occupied a veritable no-man’s land between two US Army Corps.

Lanzerath itself was unremarkable, having fewer than ten houses with wooden framework construction that could not withstand enemy fire. However, the village was situated about 300 yards south of a key road junction that connected Buchholz Station to the town of Losheimergraben. Northwest of Losheimergraben lay a major road network which would become a primary route of advance for the German Sixth Panzer Armee (Tank Army) during Operation “Wacht am Rhein” (The Watch on the Rhine) which would go down in the annals of history as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

The Sixth Panzer Armee was under an old veteran, SS Oberst-Gruppenfuhrer (General) Josef ” Sepp” Dietrich who intended to use the road network to reach the Belgian city of Liége.

As night fell on western Europe on 15 December, neither Lt. Bouck nor his men suspected that they had an engagement with history in the morning.

One of the 105,000 ASTP trainees to be reassigned to combat divisions was the postwar giant of postmodernism, Kurt Vonnegut, who was assigned to the doomed 106th Infantry Division. Like the men of the I&R Platoon in the 394th Regiment, Vonnegut was also an I&R member, of the 423rd Regiment.

The Setting

Lanzerath was problematic. Although Belgian by map, the village was a hotbed of German sympathizers, having been a part of Germany until the Treaty of Versailles in 1918. This appears to have partly frustrated the I&R Platoon’s core role of identifying enemy units in the area.

The army’s Field Manual 7-25 described the main function of the I&R platoon as being the eyes and ears of the regimental commander. Their tasks were to gather information about enemy forces and reconnoiter terrain not readily accessible to infantry units. They were also supposed to provide early warning to the regiment about enemy forces, regain lost contact with adjacent, attached and assigned friendly units and identify the flanks of hostile forces. Another role was to search undefended or captured towns and villages, and inspect captured enemy equipment and positions. (For more information, see: “Headquarters Company, Intelligence and Signal Communication, Rifle Regiment”, US Army Field Manual 7-25, 1942)

I&R platoons were supposed to have men with above average intelligence. Each division in the US army from the mid-1930s to the end of the 1950s had at least one I&R platoon within regimental headquarters companies.

The I&R platoons consisted of a headquarters and three reconnaissance squads. The platoon headquarters had one jeep while each squad had three jeeps, some of which carried radios. The soldiers were all trained as infantrymen but they operated as scouts.

The Table of Organization & Equipment (TO&E) authorized 25 troops by 1944 plus seven ¼-ton vehicles (jeeps). The regimental S-2s (intelligence officers) trained the men further in reconnaissance and information-gathering methods.

The I&R Platoon took over dugouts prepared by the men of the US 2nd Infantry Division, which had exited the area to prepare for an attack on the Roer River dams to the north. The dugouts were located at the edge of a heavily wooded area to the west and north of Lanzerath.

The position was located approximately one-half mile outside the 99th Division’s sector boundary.

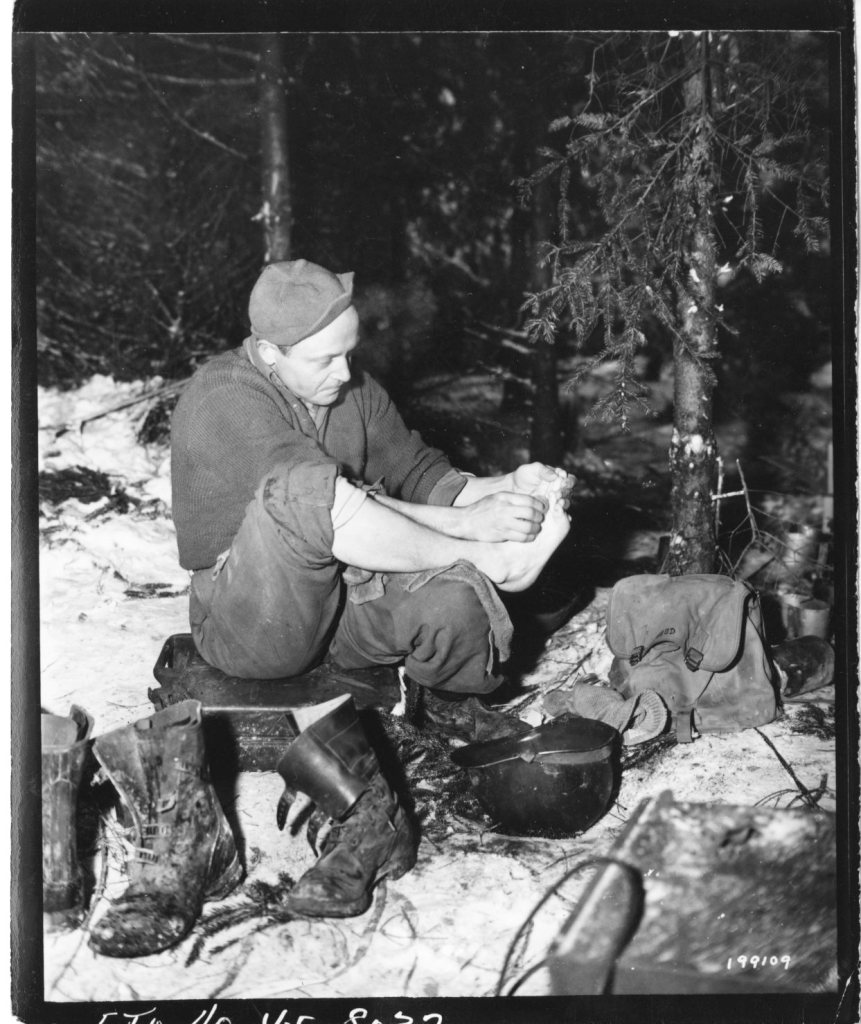

Lanzerath was on sloping terrain, with a draw to its east. The location of the I&R Platoon on the high ground gave it a stellar view of the landscape beyond the village, leading to Germany in the east. However, the platoon was not deployed at full strength. Seven members were at the regimental command post at Hünningen or had been sent back further to the rear after they developed health problems such as trench foot.

Within the village itself, about 400 yards to the right of the platoon along the southern edge of Lanzerath was a 55-man detachment from the 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion and the 14th Cavalry Group. The tank destroyer unit (1st Platoon, A Company), had four towed anti-tank guns, three jeeps and several trucks.

Also in the village was a four-man team of American artillery observers from C Battery, 371st Field Artillery. The team was holed up in a three-story house within Lanzerath, which gave them a view, down the east valley, of the distant town of Losheim.

The closest American combat unit in strength was the 1st Battalion of the 394th Regiment, located nearly 800 to 1,000 yards to the north, at Losheimergraben.

The I&R Platoon had managed to acquire a surplus of unauthorized weaponry beyond their standard complement of 23 M1 Garand semi-automatic rifles and two carbines. These included several Browning automatic rifles (BARs), anti-tank bazookas, a .30-caliber light machine gun and an armored Jeep with a 0.50 caliber heavy machine gun.

The men also had a large number of grenades plus excess ammunition.

Some of the men in the I&R platoon

The men began to reinforce the hilltop position with four or five-inch logs, cemented together with mud and dirt. This allowed them to withstand mortar and small-arms fire. The dugouts were expanded to allow two men to stand on the ground with their line of vision being on level with slit openings created for their weapons.

Bouck and his men created overlapping fields of fire. The Jeep with the machine gun was placed in a defilade position, which allowed it to sweep the field in front of the village.

The fields ahead were bisected by a farm fence about four feet high. It was a natural aiming point. The Americans zeroed their weapons to this fence.

“We were placed into well-concealed positions on a wooded crest of a ridge which overlooked a clear slope down to and beyond a road which connected Lanzerath to our right and immediately south, and Losheim somewhere off to our left and north,” Leopold said.

A cold wind interspersed with periods of snowfall prevailed in the area. A storm had blanketed the area with four to five inches of snow, camouflaging the the American positions.

The platoon set tripwires linked to pebble-filled cans to signal infiltrators. US patrols then went into Lanzerath. Members of the platoon not on guard duty rested in a log cabin built approximately 390 to 400 feet behind the dugouts.

Twice daily, Private Sam Oakley, a platoon member who had been detached to the regimental command post at Hünningen, drove up in a jeep stocked with food, supplies and mail.

The Stage is Set

The sector appeared quiet until the night of 14 December when a spurt of heavy artillery fire manifested to the north. Another platoon from the 99th Division reported hearing the noise of armored vehicles and heavy equipment. This was reported to regimental headquarters.

Bouck as a sergeant in the US Army’s 35th Infantry Division in 1940. He enlisted with the Missouri National Guard in 1936 at 14. The money he made aided his family which had been struck by the great depression. By 16, he was a Supply Sergeant. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he was offered entry to Officer Candidate School (OCS). He graduated in August 1942, in the top 10 of his class.

The morning of December 16 began ordinarily enough. At Lanzerath, Lt. Bouck observed the snow, two to four feet deep, covering the fields, extending for 200 yards from his platoon foxholes to the most peripheral house in the village.

The day was cold, the temperature in the low 30s (Fahrenheit). The wind chill exacerbated a biting wind. Fog rolled out in front of the platoon area.

At 5.25 am, a fierce artillery barrage tore into the American lines across the whole northern front, pummeling the landscape until nearly 7 am. The men of I&R platoon cowered in their dugouts. For the four-man team of American artillery observers, the display of German firepower was a discomfiting demonstration of their own trade.

The team commander, Lt. Warren Springer of the 371st Field Artillery, would say later that while there had been German shelling around Losheim before 16 December, nothing had prepared them for the scale of the enemy barrage on the 16th.

“The area in front of our observation post was blackened by a concentration of artillery shells that had fallen short by about fifty yards. The concentrated pattern made it clear that the enemy knew that the house was used as an observation post,” Springer said.

The memory of a confrontation he had with a local civilian a day before came flooding into his mind. The man had been acting suspiciously. It seemed plausible that the man had betrayed their location to the Germans.

At about this time, German troops of the 9th Regiment, 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division were advancing westwards. Their objective was to clear a series of villages to allow the armor of the elite 1st SS Panzer Division to move on their objective, the distant Meuse river.

The activities of the Fallschirmjägers reflected the leading edge of clear (if not fantastical) orders issued to the German Sixth Panzer Armee. The army was to advance for a hundred miles through the Ardennes to reach the port city of Antwerp. The timetable was rigid.

On the first day, Dietrich was required to shatter the American lines and break out onto the landscape beyond. On the second day, the Sixth Armee had to ensure the advance of its mobiIe units past the restricted terrain present in the 99th Division’s rear. By the evening of the third day, Dietrich had to be at the Meuse River. A bridge had to be secured across the river, to be followed by a crossing on the fourth day.

The schedule was partly inspired by a swift dash achieved by the late Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and the 7th Panzer Division during Germany’s Blitzkrieg (lightning) campaign again western Europe in May 1940. Four years ago, Rommel had reached the Meuse by nightfall on the third day of his advance. But conditions in the winter of 1944 were vastly different from the spring of 1940.

Dietrich did not mince words in private.

“All Hitler wants me to do is to cross a river, capture Brussels, and then go on and take Antwerp! and all this in the worst time of the year through the Ardennes where the snow is waist deep and there isn’t room to deploy four tanks abreast let alone armored divisions! Where it doesn’t get light until eight and it’s dark again at four and with reformed divisions made up chiefly of kids and sick old men and at Christmas!”

The Battle Begins

The German paratroopers at the vanguard of the German advance were elite on paper but their leadership was deficient. Most of the officers in the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division were ex-Luftwaffe (air force) men who had limited experience in directing ground operations.

At the village of Hüllscheid, on the way to Lanzerath, a German paratrooper, Obergefreiter (Private First Class) Rudi Frühbeisser, remembered his battalion encountering and tackling scattered American resistance. “To our right, the road from Losheimergraben is coming down. So forward on our left. By a row of high firs we proceed with caution. Suddenly a heavy machine gun opens up!”

Such minor firefights were sufficient to delay the progress of the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division, as its officers lacked tactical dexterity.

Back at Lanzerath, the shelling died down. It had severed Bouck’s telephone line to the regiment. The sole means of communication was now by SC-300 portable radio.

Contacting the headquarters (HQ) staff using the radio, Bouck asked if the platoon could pull out. However, his commanding officer (CO), Major Robert Kriz (a veteran of the North African campaign), had other ideas. He asked Bouck to send out patrols to determine points of possible German ingress.

As the patrols went out, Bouck and his men were stunned to see vehicles of the 801st Tank Destroyer Battalion hasten out of Lanzerath and go tearing off up the road towards the Buchholz train station, to their rear.

Lt. Springer of the artillery observation team just managed to stop one of the crews, to ask what was going on. Breathless with excitement, the crew shouted that a strong German force was advancing up the road.

Springer immediately called up the divisional fire direction center using his own radio and asked for the road 200 yards south of their observation post to be shelled. The center responded that they were under attack by German infantry and could not execute a fire mission.

A short time later, a jeep carrying two or three GIs raced into the village from the south. The GIs told Springer and his team that they were on their way to a prepared defense position elsewhere. They advised the observation team to join them as the Germans were right on their heels.

Springer and his men jumped into the Jeep and travelled with the men for a short distance north on the Lanzerath road. Upon nearing the positions of the I&R Platoon, the artillerymen disembarked from the jeep and followed a trail which led them straight to the I&R Platoon area.

Elated to see them, the I&R troops directed Sergeant Peter Gacki, Technician Fourth Grade (Sergeant) Willard, and Springer to one of the dugouts. The fourth man, Technician Fifth Grade (Corporal) Billy Queen was directed to another dugout. They were just in time.

The 9th Fallschirmjäger Regiment’s 1st Battalion, 500-men strong, marched into Lanzerath.

An account by a German paratrooper, PFC Rudi Frühbeisser of the 1st Battalion, 9th Fallschirmjäger Regiment who fought at Lanzerarth, was useful in adding a German perspective to the battle. Frühbeisser, however, is not a wholly reliable source. His 1977 book, “Im Rücken der Amerikaner” (Behind the Americans) which detailed cinematic-style actions by his unit during the Battle of the Bulge, was celebrated upon publication. According to Germany’s Spiegel magazine in 1978, Frühbeisser even became an honorary member of the US 99th Infantry Division (against which he had fought during the Battle of the Bulge). However, some of the non-Lanzerath-related events described by Frühbeisser in his book are fanciful and questionable. (Image from Hans Weijers, “The Losheim Gap/Holding the Line, Volume 1”)

Bouck once again called up Major Kriz who ordered the platoon to hold their position and that reinforcements would be sent.

But Bouck was already missing two men. Tech Sergeant Bill Slape and Private John Cregar, had been cut-off in the village. They had been in the top floor of a house in the village when German troops had barged downstairs. Unable to escape, the two men hid. When the Germans left the house, Slape radioed Bouck about their situation.

Bouck sent Corporal Aubrey McGehee, Private James Silvola, and Private First Class (PFC) Jordan Robinson across the road, to divert the Germans from Slape and Creger. The party crossed the road, crept along the ditch to get close to a building located to the left of the village. From here they intended to fire on the Germans.

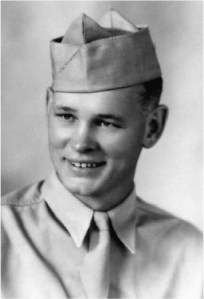

Meanwhile, I&R Platoon member, PFC Bill “Sak” James (nicknamed for his original family name, Taskinakas), monitored the radio with another I&R member, Technician Third Grade (Staff Sergeant) James Fort.

Bouck told his men to hold their fire as some 100 German paratroopers, with their distinctive mottled garb, crossed the platoon ambush point, and walked towards the crossroads at Losheimergraben.

To Bouck’s unease, the German column stopped within the village. Bouck studied them with his binoculars. As he contemplated issuing orders to open fire, a 13-year-old blonde-haired girl ran out of a house at the northern end of the village.

The girl, Tina Thelen-Sholzen, shouted something in German to the troopers and to Bouck gazing through his binoculars, she appeared to point directly at the American positions.

After the war, Thelen-Sholzen told Marcel Vaessen (a Lanzerath-based historian) that the German officer had asked her if she had seen Amis (Americans). She had responded by saying that, “…this morning I saw a few US trucks moving in the direction of Buchholz,” pointing at the road as she spoke, she added.

Vaessen believes that Buock misunderstood this gesture as pointing to his platoon. According to Vaessen, Thelen-Sholzen was unaware of the presence of the I&R Platoon in the low hills beyond the village.1

In any case, a German officer barked orders and the paratroopers dove for cover.

Cursing, Bouck waited for the girl to return to the house before he ordered his platoon to open fire. A hail of American gunfire flashed across the 200 yard meadow towards German paratroopers.2 A bullet grazed the German officer, Captain Schiffke. Nearby, another bullet plunged into a German weapons specialist, PFC Federowski. Simultaneously, a PFC, Bradel, from Vienna, was killed. Seconds later, PFC Willi Kölker cried out and toppled, a bullet wound in his thigh. As the gunfire raged, an explosion erupted near the paratroopers.

Meanwhile, Slape and Creger were on the move. Without waiting for the diversion, the men slipped out of the house they were in and fled into a nearby barn. Crawling under stationary cows, they sprinted towards nearby woods.

At about this time, McGehee, Silvola, and Robinson stumbled upon a group of Germans. A firefight erupted. The three Americans would later say that they wiped out the platoon-sized force of Germans. But they were soon under fire from other Germans, cut off from the rest of the platoon, and harried further north up the road towards Losheimgraben.

In the midst of this carnage, Slape and Creger reappeared in the woods held by the I&R platoon. Slape was ailing. He had fallen while crossing the Lanzerath-Losheimgraben road and had injured several ribs.

German survivors of the 9th Fallschirmjager’s 1st Battalion regrouped with members of the 2nd Battalion for a frontal attack. The renewed German attack went across the open field towards Bouck’s positions. It was a tactical blunder which showed the inexperience of the German regimental commanders.

The German paratroopers made it as far as the barbed-wire fence before they were riddled with gunfire.

The commander of the German 6.Kompanie, Captain Theetz, was hit and fell. The crew of an MG42 crew (Lance Corporal Hoffmann, Private First Class Ollermann and Private Jähring) were wiped out moments later, all felled by expert headshots. A bullet smashed into the shoulder of another man, Sgt. Otto Pleie, who happened to be a platoon commander and a veteran of Normandy. At about the same instance, First Lt. Grau of 4.Kompanie, together with two other soldiers (Sgt. Ilk and PFC Weishäupel) were hit and wounded.

Two more paratroopers who attempted to move forward were hit in the head and killed. One was PFC Klein, the leader of a tank-killer squad. The other was a Private Noak.

Bouck asked Springer if he could bring artillery fire to bear on the Germans.

“I told him I would try, but they were under attack back in the rear area and might not be able to respond,” Springer remembered later. “I did get through on the radio and asked for artillery fire in front of our position. I was told they would try to give us artillery support as soon as possible, but reinforcements were out of the question.”

A short time later some American shells fell ahead of the US positions. Springer corrected to bring the shelling closer to the American dugouts. When he saw German reinforcements and armored vehicles passing the house which they had used as an observation post, he directed shelling against the main road.

“A few more rounds came in, but they were still too far to the right, and I asked for a further correction. Just then there was a loud crash just in back of our dugout and the noise of shattered glass,” Springer said. “At that point my radio went dead. I don’t know if it was a mortar shell or machine-gun fire that hit our jeep, but I knew that was the end of communication with our firing batteries.”

Springer waited for more American artillery to break up the German attack. He thought he heard shelling in the village. He peeked up over the dugout to see where the shells could be landing. Twigs above his head started dropping from an overhanging tree branch.

In horror, Springer realized that bullets were smashing into the tree. “Like a turtle, I quickly pulled back into the dugout,” he said.

No more US artillery arrived. It was likely that the abrupt disruption of radio communications had led the fire direction center to believe that the observation team had been captured.

By now, McGehee, Silvola, and Robinson, having been cut-off from the platoon, were moving north in the hopes of reaching the 394th’s 1st Battalion at Losheimergraben.

They approached a road bridge spanning the railway line which cut through the landscape from Losheim town to Buchholz station. The bridge had been blown. As they climbed down the 30-40-foot railway cut, troops from the German 12th Infantry Regiment appeared, dressed in all-white winter clothing. The Americans opened fire.

Return fire tore into Robinson’s thigh. Silvola was hit in the left elbow. The Americans dropped several Germans but there was no possibility of winning. The three men were captured.

Continued Resistance

Back at Lanzerath, the German 1.Kompanie was pinned down amid an old German minefield at the edge of the tree line. The German 2.Kompanie tried to storm the woods. A hail of fire rushed out to greet them. A platoon commander, 1st Sgt Karl Quator and several men, Corporal Fischer, Privates Rench, Roth and Private Heube, were killed. A second platoon commander was wounded.

Another man, PFC Hans Winter, a veteran of the Russian front and a card-carrying Nazi, was wounded. A one-time orator in the Nazi party, Winter shrugged off his injury and appeared immune to the heavy American fire.

“So, Hans, you with your golden party membership badge, are impervious to more than a scratch?” A trooper called to him.

Unfazed, Winter calmly walked back to the village to have his wounded bandaged by a medic.

At about this time, Captain Woitschek’s 3.Kompanie was pinned down in the left part of the village. The paratroopers, in their mottled garb, stood out in the dizzying white of the landscape, drawing heavy American small-arms fire.

A volley plunged into a group of paratroopers. A platoon commander, Sgt. Major Schiele, stumbled and collapsed. Someone turned him over and called out: ‘Headshot!’ Two other men, Corporals Mayer and Schmidt were wounded.

A medic, Corporal Matthieu, ran over to help the wounded. A bullet plunged into his head and he keeled over. A second medic, Corporal Schmidt, who came over to help, was also hit in the head.

A stalemate set in. The second German attack unfurled in the mid-afternoon which only resulted in more casualties to the paratroopers. Their ineptitude was a boon to the American platoon. The Germans made no attempt to maneuver or call in fire support.

While Bouck was on the radio with an officer back at regimental headquarters (Lt. Bungee), a bullet smashed into the transmitter. Bouck had been fortunate. Private Louis Kalil was less so. As he fired from his fortified dugout, a German rifle-fired grenade came flying through the narrow, 18-inch aperture and struck him on the side of the face. The grenade failed to explode but the impact of the projectile fractured Kalil’s jaw and cheekbone, forcing several teeth into the roof of his mouth.

Private George “Pappy” Redmond bandaged Kalil’s face but the pain became excruciating for Kalil. Meanwhile, some distance away, Tech 5 Billy Queen of the artillery observation team had been killed. He was the only defender to die during the battle.

The Germans asked for a truce. Bouck agreed but in the midst of this ceasefire, PFC Milosevich observed a German medic behaving suspiciously. Mortar fire began landing near his dugout. Convinced this medic was guiding the rounds, Milosevich opened fire, killing the German.

As the fighting resumed, Bouck felt himself to be in an impossible situation. “The communications were out, ammunition was running low, the wounded increasing, and apprehension running high,” he said. “I told ‘Sak’ to get Slape, [Sergeant William] Dustman, and Redmond. Our evaluation was not impressive. We realized heavy fighting was taking place north of us at 1st Battalion and to the northwest where 3rd Battalion was in reserve at Buchholz Station. Later, of course, we learned it was the German 12th Volksgrenadier Division battling the 1st Battalion and the same unit reaching Buchholz Station by way of the railroad cut.”

Realizing they had been cut off from the rest of the division, Bouck told Slape to send Corporal Sam Jenkins and Corporal Robert Preston back to the regiment (or at least to 3rd Battalion), to inform HQ about the platoon’s plight. Both men set off and were never seen again by the platoon during the war.

By the time the two Jenkins and Preston reached the regimental command post at Hünningen on 18 December, the command post had withdrawn to Elsenborn. Out of ammunition, both men hid in a hayloft only to be discovered and taken captive by German troops on the following day.

Meanwhile, back at Lanzerath on the 16th, the Germans attacked the I&R platoon for a third time that afternoon. At about this time, the platoon’s only heavy ordnance, the .50 caliber heavy machine gun gave out. The barrel was so hot that the gun was already firing on its own. Then, the barrel warped. As dusk approached, Bouck and the rest of the survivors contemplated withdrawal.

But it was too late. Suddenly, the German paratroopers were all around them and in-between them. PFC “Sak” James leaned out of his emplacement and unloaded his last clip at two incoming Germans 20 yards away. Return fire ripped into the emplacement as James ducked for cover.

The Germans had also summoned two assault guns for support.

Bouck, who was in the same dug-out with James, saw the barrel of the German automatic weapon probe their emplacement from behind. He instinctively pushed it away and the gun erupted into life, blasting James at close quarters.

James slumped, having taken five to six bullets to the right side of his face. Bouck felt himself being grabbed and pulled upwards by a pair of German hands. Another German shone a flashlight down at James and seeing his mangled face, uttered an oath of horror. The right side of James’ face, from his nose to his right ear, had been torn up. His right eyeball hung from its socket.

With American resistance neutralized, the Germans were finally able to take stock of their dead, the dying and the mauled who lay en masse in the fields. Despite their anguish, the German paratroopers made no attempt to exact vengeance on their captives. The prisoners were herded into a building (the Cafe Palm).

Sgt. Gacki of the artillery observation team later said that he and Wibben were put to work, carrying German wounded from the top of the hill to the Lanzerath. They looked for the last member of their crew: Tech 5 Bill Queen. Only later did they learn that Queen had died.

The body would later be found by members of another forward observer party from C battery in January 1945.

At the cafe, Bouck was preoccupied with the ailing James who was passing in and out of consciousness.

“I removed a picture of his girlfriend (Chloe) from his wallet, placed the picture and the bible on his chest and said a few words of prayer, and told him I pledged that we would see each other back in the States. I told him we were being separated now, and placed the picture back in his wallet and put it and his bible in his field jacket pocket, and said, ‘Good-bye.’ He could not speak, but I am certain he heard me, because he squeezed my hand,” Bouck said.

Effect

At about midnight, a group of SS panzer officers stormed into the café. Among them was an irate 29-year-old German Waffen SS lieutenant colonel, whose job it was to seize the bridges over the Meuse river. The orders that had been issued to this officer, SS Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper, were rigid. As the leading element of the 1st SS Panzer Division, Peiper should have already been on his way past Hünningen. However, the resistance posed by the I&R Platoon had created a massive traffic jam of vehicles and troops leading into Germany.

Peiper’s battlegroup was mobile but cumbersome and especially vulnerable to the vagaries of the road. His unit comprised 30 King Tiger tanks, 72 medium tanks (some of which were equipped with a then-revolutionary infrared night-vision system), 80 half-tracks, and approximately 4,000 troops. By the time Peiper managed to reach the town of Losheim it was already 7.30 pm.

Urbane and ruthless, Peiper had the key job of reaching the Meuse river bridges. An SS fanatic, he was known for the ability to make profound tactical analyses. However, his military prowess started to wane by 1944. In early August, while in Normandy, he suffered a mental breakdown.

Arriving in Lanzerath shortly before midnight (after losing ten vehicles to an old German minefield), Peiper found the 9th Fallschirmjäger Regiment in a demoralized state. To his fury, he discovered that the paratroopers had made no attempt to gauge the depth of American defenses in the Lanzerath area.

Upbraiding Oberst (Colonel) Helmut von Hoffmann (commander of the 9th Fallschirmjäger Regiment) in full view of the paratroopers and the American prisoners, Peiper demanded that the regiment accompany his tanks as they cleared the sector.

Despite witnessing this scene Bouck and his men went into captivity believing that they had achieved little. They did they know at the time that their resistance had disrupted a major avenue of advance for the Germans while simultaneously protecting the southern flank of the US 394th Regiment.

In a 1939 US Army book Infantry in Battle, prepared under the direction of the-then Colonel George C Marshall, the authors wrote that in the process of effecting miracles “resolute action by a few determined men is often decisive.” And so, it was with the I&R Platoon.

The platoon’s resistance meant that the 1st SS Panzer Division which was to seize the Meuse river bridges was delayed for a critical 18 hours. This spelt the failure of the German advance in the north. However, because the I&R Platoon had been cut-off and unable to report on their actions even by radio, this fact escaped the US Army for 22 years.

Postwar historians would attribute hundreds of German casualties to the platoon. The paratroopers of the 1st Battalion were told that their unit had suffered 16 killed, 63 wounded, and 13 missing.

In 1947, Hugh M Cole in his seminal work, The Ardennes: The Battle of the Bulge, briefly mentioned the platoon but did not discuss their pivotal role. Their story was revealed for the first time in John S D Eisenhower’s 1969 book, The Bitter Woods. But even this did not generate greater interest in the battle.

It was only when James, who had survived the war, perished in 1979, that things began to mobilize. James’ wartime injuries had cut his life short. He died days after his 36th operation. The death prompted columnist Jack Anderson to write about the bureaucracy which had denied the platoon its recognition. The pieces attracted the attention of New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner who raised the issue with a friend, House Speaker Thomas P O’Neill (D-Massachusetts).

Three years later, a hearing was held in congress in 1981. Following the support of two Presidents, special legislation was passed that allowed the army to circumvent a regulation that recommendations for awards be made within two years of the deed.

The New York Times reported that on 9 October 1981 James’ widow had accepted a Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) on behalf of her late husband. The award was presented on “national television, during a special ceremony arranged by Steinbrenner at Yankee Stadium before the opening game of the American League championship playoffs,” according to the newspaper.

On 25 October 1981, during a formal ceremony, the remaining 17 combatants of the I&R Platoon were awarded their own medals: three DSCs, five Silver Stars, and ten Bronze Stars with V (for valor) devices. All four men of the artillery observation team, including the late Billy Queen were awarded DSCs. Bouck had already been awarded a Silver Star (in absentia) while a prisoner of war in 1945. He, Slape, and Milosevich were now among those bestowed with DSCs.

The I&R Platoon was also conferred with a Presidential Unit Citation (PUC), the US military’s highest award for extraordinary heroism by a unit in action against an armed enemy.

The platoon had become the most heavily decorated small unit, for a single combat action, in World War II.

SOURCES 1. CAVANAGH, William C C, The Battle of Elsenborn Ridge and the Twin Villages, Pen & Sword, 2004. 2. EISENHOWER, John S D, The Bitter Woods: The Battle of the Bulge, Putnam, 1969. 3. KERSHAW, Alex, The Longest Winter: The Battle of the Bulge and the Epic Story of World War II's Most Decorated Platoon, Penguin, 2015. 4. SPILLER, Roger J. (ed), Combined Arms in Battle since 1939, Chapter 7, Miracles, US Army Command and Staff College Press, 1992. 5. WIJERS, Hans, The Battle of the Bulge: The Losheim Gap/Holding the Line, Volume 1, Stackpole, 2009. 6. GORFAIN, Adam, "The Story of War Hero PFC James. A War Hero Four Decades Later," 8 November 1981, https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/08/nyregion/story-of-pfc-william-james-war-hero-four-decades-later.html (Accessed 1 May 2022)

Normandy, the Bulge, I woulld love to see Akhil put some effort in doing an article on Market-Garden, especially the 82nd. 🙂

Hi Marco, I have never independently researched Market-Garden because there is already some great writing about the campaign – including the masterpiece by Cornelius Ryan.

Ditto for the maps. There are already so many good, localized maps of the battles in the Arnhem, Nijmegen and Eindhoven sectors published by others.

Go Tarleton Texans!

Another outstanding article. Thanks

Great article…and maps are seriously next level. Good to catch Lanzerath Church which is now in a different location to 1944.

The FJR.9 was at 70% strength, 2450 men, 1200 of which were “sturm-einheiten.” (Roppelt, auf der Spur). Better shape than 8 or 5 FJR which were at 30%. Happy to send screen shots, amazing book though I need to use translate, a lot!

Hi Nigel, thanks for your message and your kind comments.

If you could send the scans to my email address (akhil213@yahoo.com), that would be helpful. A translation would be better!

Great article, really! I plan to visit the area later this year. Excellent, superior maps!!

Thanks, Livio. I really appreciate your comments.

Hi Akhil, I’ve found out an info concerning the girl who “gave out” the position of the I&R platoon to the Germans. According to what I found her name is Tina Scholzen (same name of the Cafè!). If the info is confirmed, may be you’ll think about to add it to your story. Here you are the link

http://digitalcapricorn.com/site/lanzerath-ridge/

B/R

Livio

Hi Livio, thanks for this bit of information. I’ll check out the link.

Roger, you’ll find the info in the Companion Book (download).

Congrats for the article!!!

Many thanks. Almost a year’s worth of work.

Pingback: Beer & The Bulge: The Longest Winter – itsabrewtifulworld

In Charles Whiting’s Death of a Division, Whiting confirms the girl who told the Germans about the American’s presence was Tina Scholzen, in 1967 one of the Americans soldiers returned to Lanzeroth and met her, she was then the mother of three children.