THE ANTONY-FRESNES-BERNY TRIANGLE

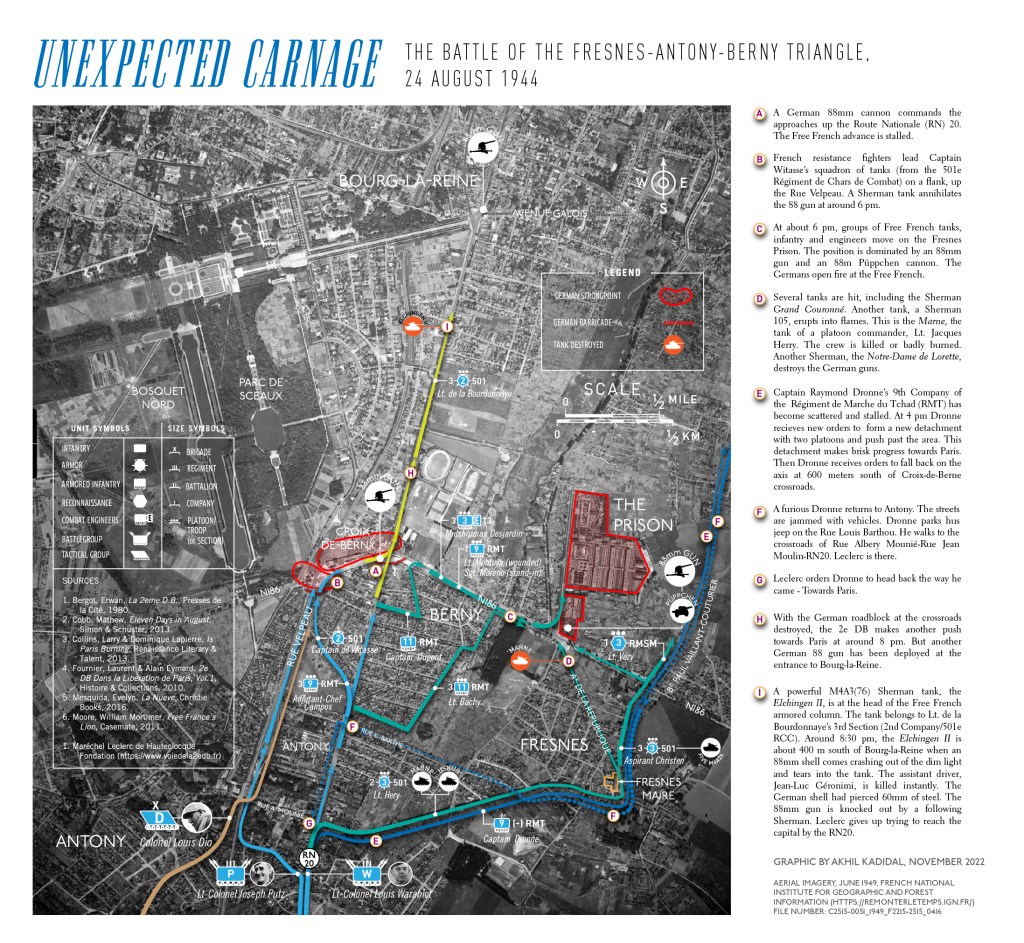

Putz’s battlegroup began to encounter serious resistance as it approached the industrial town of Antony, a suburb of Paris. The Germans had focused their defense into a small triangle running from Antony to the massive hulk of the Fresnes prison to the crossroads at Croix de Berny.

Antony was liberated quickly enough by one column of Free French driving up the Route Nationale 20 (RN20). A second column emerged from the old Chartres Road.

But then an 88mm cannon strategically positioned at the Berny crossroads turned its barrel on the arriving Free French.

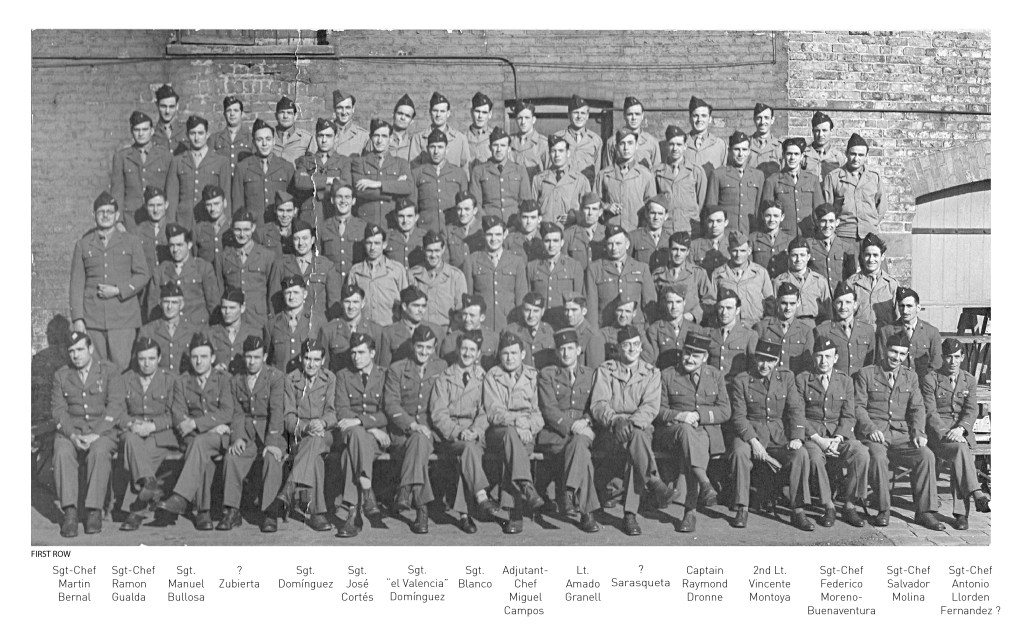

The 1st Platoon of the 9th Company of the Régiment de marche du Tchad (RMT) under a Spaniard, 2nd Lt. Vincente Montoya (just 21 years old), arrived in front of a butcher’s shop on the right side of the highway. Montoya, a former infantry officer in the old Spanish Republican Army, had distinguished himself in Normandy. He had already won the French Croix de Guerre medal with the silver star for heroics.

Known as the “Nueve,” the 9th Company was a unique unit. Some 146 of its 164 troops were Spanish or of Spanish extraction (at least four were Spaniards born in Morocco). The company’s halftracks carried the names of the long-lost battlefields of the Spanish Civil War: Guadalajara, Teruel, Ebro, Santander, Brunete, Guernica … Other halftracks carried French nicknames, such Resistance, Nous Voilà, Cap Serrat and Rescousse. Dronne’s own Jeep carried the French phrase: Mort aux Cons (Death to Cunts). (Mesquida, loc.1993, 40%)

The company had disembarked on the hallowed ground of France at Magdalena Beach, near Sainte-Mère-l’Église on 4 August. This area has been “Utah Beach” on D-Day. The disembarkation operation was slow. The men had sung the “La Cucaracha” in derision.

Nearly all of the sergeants and lieutenants in the company were Spanish. Second-in-command was Lt. Amado Granell, a 45-year-old Valencian and a former member of the Spanish foreign legion.

Having joined the legion as a minor without the consent of his parents, Granell had left the army in 1922 with the rank of sergeant. After settling in Alicante as a cycle shop owner, he began participating in labor union movements in the interwar period.

When the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936, Granell joined the Levante battalion in which he eventually became a Captain. By December 1938, he was the commander of a brigade. But with the opposing Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco on the verge of victory in 1939, Granell left Spain. He found passage on the Stanbrook, the last English merchant ship to leave Alicante before the nationalists arrived. All Granell had were a few possessions and his machine gun, Dronne recalled in 1964.

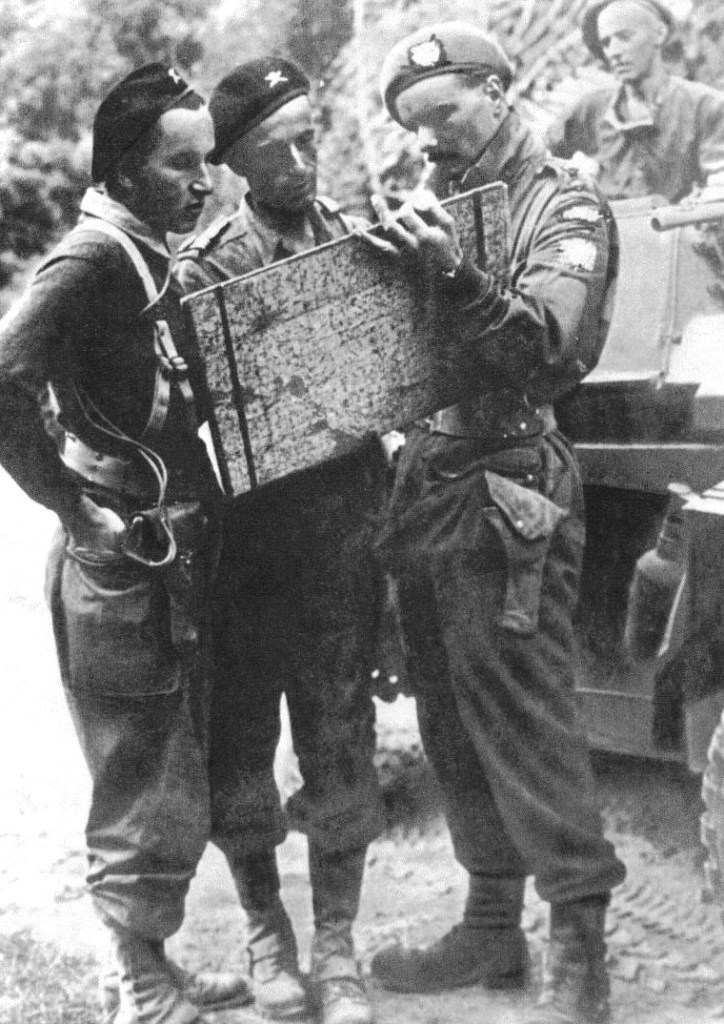

When the Stanbrook arrived in Oran, Granell (like nearly all Spanish exiles) was shunted by the French into a disciplinary camp. After the Allies landed in Morocco, he was able to join the Corps Francs d’Afrique in December 1942. During the Tunisian campaign, he met Major Joseph Putz who offered him the opportunity to join the 2e DB under the command of General Leclerc. In this way, he had come to join the Nueve. Such experiences were not alien to many others in the company. (https://www.24-aout-1944.org/La-journee-du-24-Aout-1944/)

The 18 non-Spaniards in the company comprised one Brazilian, one Mexican, two Portuguese, six Frenchmen, one Italian anti-fascist, one Argentine, one Romanian and three German anti-Nazis (including Staff Sergeant Johann “Juanito” Reiter, the scion of an officer in the Kaiser’s army who the Nazis had murdered). (Data compiled by author & Dronne, A Spanish Company in the Battle for France and Germany, loc. 107, 15%) Reiter had been a cadet in Munich during the Weimar Republic. He had subsequently seen action in the Spanish Civil War as part of the General Staff of the Lenin Column. (Antonio San Román Sevillano, August 24-25, 1944: The liberation of Paris) This column was made up mostly of individuals from the Catalonian Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) – the same group that the British writer, George Orwell, had served with.

Rounding out the non-Spaniards were two Armenians, including Private Bedros Krikor Pirlian, a tailor from Istanbul, who had become Dronne’s aide). Some two or three of the group were stateless individuals, according to Dronne. (Data compiled by author & Dronne, A Spanish Company in the Battle for France and Germany, loc. 107, 15%)

The company was a novelty to those those had been in Spain during the war. During the advance from Rambouillet, the famed war photographer, Robert Capa, had been among those who had hitched a ride with company. Capa, who had photographed the Spanish Civil War, had talked his way aboard the halftrack Teruel by declaring his civil war antecedents: “Y yo soy uno de vosotros” (‘And I am one of you’). (Rankin, loc. 439.4, Ch. 12, 63%)

Meanwhile, back at Antony, Dronne and the rest of the “Nueve” were still down the road. Montoya’s platoon deployed their 57mm cannon road, facing it up the road towards the crossroads.

The owner of the butcher shop set up a table on trestles in front of his shop and began to distribute snacks to the soldiers. The war appeared to be far away. (Fournier & Eymard, 2e DB dans la Liberation de Paris Vol. 1, 125)

A distant boom sounded. A split second later, an 88mm shell burst tore into the front end of the shop. Lt. Montoya was hit by shrapnel. He fell bleeding. His second-in-command, Chief Sgt. Federico Moreno-Buenaventura, scrambled to assume command. (ibid)

Other Free French units on the street also began to take fire. For several hours, Battlegroup Putz was pinned until a decision was taken to attack the 88mm gun from the left flank. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/antony/) Captain Dronne ordered his 3rd Section under a giant of a Canarian, Chief Warrant Officer Miguel Campos, to support the attack by disabling a German flak battery which was firing on the detachment.

Campos and his men destroyed four 20 mm flak cannons and several machine gun teams and took 25 prisoners. But they had suffered one fatality – one of the company’s two Armenians – Private Ernest Hernozian-Luis.

Meanwhile, Captain Jacques de Witasse, commander of the 2nd Company (501e RCC) ordered Lt. Jean Lacoste’s 2nd Section to travel over the Rue A. Mounié on the left and then up the Rue Velpeau to RN186. The intersection of RN186 with RN20 formed the Croix de Berny. Resistance fighters under the command of the local head, Henri Lasson, guided the Free French towards the target. (Ibid.)

Lacoste’s Sherman tank, the Friedland, roared onto the RN186. The crew of the 88mm gun frantically swiveled the barrel of their gun towards the Sherman. At this range of less than 200 meters, an 88m could skewer a Sherman like a hot chisel through butter.

But the Friedland’s gunner, Branko Okretic, was faster than the Germans. His first 75mm round smashed through the 88mm gun, a tractor and then an ammunition depot, killing 15 Germans. It was about 6 pm. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/) On the other side of RN20, members of the local resistance entered a metro station to cut off the Germans at the crossroads from the German redoubt nearby – Fresnes prison.

By now, Dronne’s 9th Company of the RMT managed to slip past the battle-area with their halftracks – minus Lt. Montoya’s First Platoon which was pinned down by machine gun fire from the prison.

Captain Dronne had received the flanking order at around 1 pm. He had sent Campos to a level crossing east of the prison. The road led to Paris. Meanwhile, the 9th Company’s 2nd Platoon, under Second Lieutenant Michel Elias (a native Parisien) was ordered to cover the area between the eastern face of the prison and the level crossing. (Fournier & Eymard, 2e DB dans la Liberation de Paris Vol. 1, 125)

Leaving the fighting behind at Croix de Berny and the prison, Campos and Dronne traversed past Fresnes. Within hours, they could see the distant outlines of the Eiffel Tower. Then, the platoon began to take fire from German 20mm anti-aircraft cannons.

Meanwhile, on the right of Battlegroup Putz, Battlegroup Warabiot had become stalled at Morangins, south of Orly. Here two tanks were lost. Warabiot would experience more losses at Fresnes.

The Fresnes prison had become a major problem. Some 350 Germans of the 132nd Infantry Regiment and assorted smaller units held the complex. A battery of anti-tank guns covered the highway, including one 88mm gun and an 88mm Puppchen rocket-launcher. The guns commanded the entrances to three of the five streets leading to the prison. (Collins & Lapierre, 246)

Warabiot and Putz ordered elements of their command to attack the prison from four directions: the east, south and west and the north.

A detachment of Shermans (comprising Lt. Jacques Héry’s 2nd Section (3rd Company, 501e RCC) and Aspirant Marcel Christen’s 3rd Section (of the same company), plus infantry from Captain Emmanuel Dupont’s 11th Company of the RMT and resistance fighters advanced towards the Fresnes town hall (maire). From here, they could attack the prison from the south and the west.

Other supporting units included the infantry of Lt. Bachy’s 3rd Platoon (11th Company, RMT) with five halftracks, the 3rd Platoon of the 3rd company (13th Engineers) with one jeep and three halftracks and M8 Greyhound armored cars under under Lt. Vezy’s 1st Combat Platoon of the 3rd Squadron of the Regiment de Marche de Spahis Morocians (RMSM) and M8 Scotts of the 3rd RMT battalion’s howitzer platoon commanded by Lt. Antoine Ettori.

Meanwhile, a detachment of tanks under Lt. Albert Benard (1st Section, 3rd Company, 501e RCC), tried to approach the prison from the north. The Sherman Montfaucon destroyed a blockhouse on the Haÿ les Roses road. But the road to Choisy which ran along the perimeter wall of the prison, was dominated by German fire. Benard’s force pulled back.

Back in the south, several German soldiers under the command of Lt. Alspeter were hiding behind mounds of earth near the Fresnes town hall. Seeing the French force arriving, they opened fire. A French engineer, Dubouloz, ran up one of the mounds and was hit by three bullets. He was rushed to the Longjumeau field hospital but died.

Héry, just 22 years old, pushed on towards the prison with the rest of his unit on the Avenue de la République. In the lead was Héry’s M4A3 Sherman (the La Marne). The tank was armed with a 105mm gun. Trailing behind were the Shermans Uskub and Douaumont. In support were Lt. Bachy’s mechanized infantry. Incredibly, here too were some Spaniards. The detachment was commanded by Staff Sergeant Salvador Molina of Barcelona. The leader of the mortar group was Sergeant Le Jan Alfred, who was assisted by Master Corporal Chita. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

The Shermans headed for the prison’s main gate. The 3/11th RMT halftracks (including Staff Sgt. Molina’s 14 July 89, 8 November 42 and 18 June 4) fell further west to accompany Christen’s force. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

Héry and his men could see the looming prison up ahead. It was about 7.00 pm. A French guide leading the tanks was in a state of euphoria. Standing behind the turret, he began singing Mourir pour la patrie (“To die for my country”). Héry was unimpressed. “[The guide’s] agitation inspired no confidence in me,” he said. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

Héry was right to be cautious. His tank had come into the sights of an 88mm gun positioned at the prison. When the Sherman was within 60 meters of the gun, the German gunner, Private Willy Wagenknecht, fired. The cannon boomed.

A split second later, the monstrous 88mm shell had punched into the La Marne, bucking it slightly above the ground.

The tank’s assistant driver, Private First Class Georges Landrieux, was killed instantly, his chest blown away. Just moments before, Landrieux had been full of life, pointing out to his comrades the square bell tower of the Fresnes Church where he had been married before the war. The tank erupted into flames.

Nearby, Captain Dupont and Aspirant Christen watched in horror as one of the La Marne’s crew, his legs blown off, hoisted himself out of the burning tank and rolled on the ground. Another man, his clothes on fire, tumbled out of the turret and ran for cover. This was Lt. Héry.

Brought out from the line of fire, his skin peeling off in strips, Héry identified the amputated crewman as his gunner, 18-year-old Geoffroy de Laroche. Pulled to safety and placed on an ambulance, de Laroche would say with a smile to his compatriots: “You say goodbye to my friends for me — if I am not fortunate to be crippled at my age”. He was dead moments later. (Maurice Boverat, Du Cotentin a Colmar, 1947 (http://www.chars-francais.net/2015/index.php/classement-individuel/m-4-sherman?task=view&id=927)

Another member of the crew was the driver, Corporal Pierre Sarre, a Frenchman from Mexico. He had escaped the tank through the front cupola, his clothes on fire. German bullets smashed into his arm as he jumped from the tank. He fell hard onto the ground. As he rolled to smother the flames, he was ashen to see German infantry running towards him. He struggled for his pistol. His hands, moist with blood, found it. He pulled the gun from its holster and aimed at the Germans. To his horror, the trigger did not work. The safety was on. His clumsy fingers could not release the safety. Holding the pistol between his knees, he finally flicked the safety off.

At this exact moment, a French machine gun unloaded heavy fire into the approaching Germans. The bullets screamed just above Sarre. Tracer rounds grazed his overalls, setting his clothes on fire again. Sarre rolled again to extinguish the flames. Soon, he was being pulled by friendly hands — the infantry of the RMT. They placed him against a wall on the other side of the street before returning to the battle.

To Sarre’s bad luck, a shell tore into a house next to where he had been placed. Flaming wooden beams and rafters crashed nearby, setting him afire for a third time. Despite this, Sarre managed to survive. (Boverat)

From where his tank was, Christen said he could not see the 88mm gun because of a small brick wall at the end of the street, between the trees and the prison wall. One of Christen’s tanks, the Grand Couronné, lurched forward towards the prison. It was followed by Christen in his tank, named after the WWI battlefield Hartmannswillerkopf.

The Grand Couronné had not moved two or three meters ahead when two German shells came out of the ether and slapped onto its frontal armor before ricocheting away in a flash of sparks. The shells had impacted the tank’s sloped armor where it was the thicket. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

“It was a true miracle [that the armor was not breached] as the tank lifted from the ground with each hit,” Christen said later.

The driver of the Grand Couronné, Georges Imhoff, deftly reversed the tank. Despite this, Imhoff (a native Alsatian) recalled that the tank was hit five more times by “enemy anti-tank shells…from the main entrance to the prison… The Grand Couronné was hit four times on the front glacis and once on the body, at the rear, in the engine compartment, but without damaging the latter. From my driver’s seat, inside, I saw the armor redden under the repetitive blows of 88. I immediately turned right to save the crew and the tank. The fifth shell hit the rear of my tank.” (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

Meanwhile Christen’s Hartmannswillerkopf, began to pummel the prison gate. A shot from the tank’s gunner, Pierre Chauvet, tore into an ammunition truck foolishly placed just behind the 88mm gun. The massive explosion tore the area around the 88m gun.

The French saw their opportunity and roared forward. Barely 50 meters from the gate, a German soldier, his uniform ragged and blackened by fire, rose from the detritus of the 88m gun position and fired a submachine burst in the direction of the Hartmannswillerkopf. Christen heard a cry beside the tank and saw Captain Dupont of the RMT collapse with a bullet hole in the head.

The 88mm gun began firing at another Sherman, the Notre Dame de Lorette. “The first shell cut a tree that fell close to the tank; a second cut the tank’s antenna as it went over a bump,” recalled the tank commander, Sgt. Freudiger.

The third shell cut the tank’s tow cable. A fourth shell ricocheted off the front glacis and brushed lightly against Freudiger’s face.

“A mad rage took hold of me…,” Freudiger said. “I told Leduc (our driver) to rush towards the prison, which he did after having turned to the right, smashing through the perimeter wall (thereby covering me with dust and covering the tank with bricks).”

The Notre Dame turned left and found itself in the main alley of the prison. The tank turned right and the French tank crew saw the 88mm gun behind them. Freudiger told Leduc to back up on the Germans.

Wagenknecht and his compatriots panicked. They fled, abandoning the 88mm gun. The Notre Dame crashed into the gun. The tank then set off up the alley towards the prison, crushing all vehicles in its path. A garage door appeared at the end of a driveway. The tank smashed through it. Inside, was a bus full of Germans. The Germans opened fire, their bullets ricocheting off the tank harmless. Freudiger’s Corporal Debaume, fired his 75mm gun, blowing the bus and its occupants to bits.

The Free French crew continued to drive on until they found themselves plunging into the Bièvre river which ran along the western side of the prison. Freudiger opened the turret hatch and pushed himself out. Bullets again ricocheted off the tank. Freudiger realized he was being shot at by German soldiers on the heights of the Croix de Berny. Crawling along on the ground, Freudiger sought out his platoon commander.

The noise of a car trying to start up reached him. Following the sound, Freudiger came upon a German officer trying to start a civilian car. Seeing the Frenchman, the German took off running. Freudiger gave chase. Soon, both men were out of breath. Freudiger and German walked towards the main group of Free French accumulating in front of the prison. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

The RMT infantry swept into the prison, guns blazing. German resistance began to collapse. (Collins & Lapierre, 248) At about 8 pm, Montoya’s First Platoon (9 RMT) made contact with Christen’s platoon at the prison.

By now, Lt. Vézy’s platoon of Spahis was holding the area east of the prison, on boulevard Paul Vaillant-Couturier (today the Avenue de Stalingrad). Gunfire from the prison’s water tower tore into the area around the Spahis. The reconnaissance troops retaliated by unleashing heavy return fire from their 37mm cannons and 12.5mm heavy machine guns. The German fire ceased after five minutes.

Moments later, civilians reported that a group of German soldiers had left the prison and were fleeing northwards. Vézy was ordered to cut them off. He dispatched two armored cars to intercept the Germans. The cars found the Germans near the Rue Calmette (today Rue Gallieni). In the heavy combat that followed, the German party was wiped out. The Spahis would count nine German bodies, including a lieutenant. (https://www.voiedela2edb.fr/fresnes-94/)

The dead were buried at 9.30 pm — near the scene of their demise.

Meanwhile, the prison attack had resulted in deaths of several men from the RMT’s 11th Company. Aside from Captain Dupont, the death list included Staff Sgt. Molina, Privates First Class Gaston Doux, François Mamo and Roger Lamotte, Private 2nd Class Fernand Meunier and Private Henri Charmette. Another 19 men from the 11th Company were wounded.

Lerclec was fuming at the lethargy of the advance — his anxiety heightened by a message from Jacques Chaban-Delmas which again harkened of an image of Paris resembling gutted Warsaw. The message had been delivered via an officer of the resistance, Lt. Jacques Petit Le Roy, 28-years-old. Before the war, Le Roy had been the No 4 golfer in France.

Leclerc drafted a response intended for von Choltitz. In the letter, Leclerc said he would hold von Choltitz personally responsible for any damage to Paris or its monuments. Petit Le Roy would die trying to get the message to Paris.

Anxious to avoid Fresnes which still contained German forces, Petit Le Roy and his companions (two members of the 2e DB), had driven through Rungis in a divisional jeep. Here, a civilian joined the party as a guide. As the jeep went into Chevilly-Larue, where Petit Le Roy had hidden a bicycle he had used to travel out of Paris, they stumbled upon a group of German soldiers exiting a café. The Germans opened fire. Petit Le Roy and one of the 2e DB soldiers managed to kill one of the Germans before they were riddled with gunfire.

The civilian and the driver of the jeep escaped the exchange of gunfire. In hiding, they watched the Germans rifle through Petit Le Roy’s body and discover the letter. Remarkably, Leclerc’s warning was delivered to Choltitz.

(https://www.golfdesaintcloud.com/en/the-jacques-petit-leroy-cup) After the war, von Choltitz would tell Alain de Boissieu, the hawk-faced commander of Leclerc’s Headquarters Protection Squadron, that this was the first time he truly feared being treated as a war criminal. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 690.2, Ch. 7, 68%)

From Leclerc’s perspective, the day wore on with little hope of a breakthrough past the Antony-Fresnes-St Croix triangle. Leclerc’s mind turned to the call they had received earlier from Charles Luizet at the Prefecture of Police.

A message would be sent to the resistance to give them hope their ordeal was almost at an end. The division operated six Piper Cubs for artillery spotting. Now, one was sent to the prefecture to drop a message.

At the controls was Pilot Captain Jean Callet, 28 years old. Also in the aircraft was Callet’s observer, Lt. Etienne Mantoux, who held a musette bag containing the message. The bag had been weighted using a piece of lead.

Callet flew the Cub low over the city, crossing over Hôtel de Invalides. As he approached Notre-Dame, he saw three German tanks on the square in front of the church. The tank turrets blinked repeatedly – machine gun fire. All at once, Callet could see German troops running. Then, time appeared to slow, he saw a couple embracing each other along the Seine. German gunfire flashed past his aircraft. On rooftops, Frenchmen and women waved handkerchiefs at them.

Callet put the Piper Cub into a steep dive over the prefecture, as if hit. The fragile aircraft dove towards the earth. The open courtyard of the prefecture filled the windshield. Mantoux threw out the bag. Callet pulled up and the Cub climbed like a swallow, its engines roaring. Mantoux’s message fell into the street outside, but the resistants managed to seize it before the Germans could.

“Tenez bon,” the message read. “Nous arrivons.” (Hold on. We are coming). It was about 5 pm.

Meanwhile nearby, at the Ile Saint-Louis apartment of his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter and their daughter Maya, another Spanish exile, the artist Pablo Picasso was working on a watercolor-gouache version of the ink version of Nicolas Poussin’s 1635 masterpiece, The Triumph of Pan, which depicted an orgy in the countryside. Originally, upon taking up temporary residence at Walter’s apartment, Picasso had started two portraits of his daughter. But when the fighting in the city worsened, Picasso had turned to Poussin. (Patrick O’Brian, Picasso: A Biography, loc. 809.2, Ch. 17, 72%)

Picasso had likely chosen this project (part of his sudden interest to reinterpret historical masterpieces) to divert his attention from the battle raging outside. As it was, he had nearly been killed by a bullet when he stole a glance through a window outside at the fighting. (O’Brian, loc, 809.2, Ch. 17, 72%)

But the sounds of battle appeared to move through walls to reach him. The windows rattled with each explosion nearby. Ronald Penrose, a close friend, wrote later that Picasso began to paint The Triumph with whatever materials he had at hand — watercolors, gauche. As the noises of war continued, Picasso began to sing at “top of his voice,” to drown out the crash of guns. (O’Brian, loc, 809.2, Ch. 17, 72%)

Subconsciously perhaps, the colors of the French tricolor began to appear in the painting, reflected in the clothes of the subjects. In Picasso’s version, the vision of a man helping an inebriated Pan to his feet at the left of Poussin’s drawing was moved to the right of the piece and appears to be a man helping a wounded figure, as a helmeted figure stands above them, shielding them. (Cobb, 262)

Note: Picasso started the "Triumph of Pan" at Walter’s apartment but completed it on 28 August at his studio. It stayed with him until he died. A lithograph of the painting was made in the 1950s and this is at the National Gallery of Australia. Its current whereabouts are unknown.

Meanwhile, Choltitz was in despair. At around 6.45 pm, he informed General Blumentritt that the “the situation in Paris never ceases to deteriorate hourly.”

Choltitz added: “It is foreseeable that we will not be able to hold Paris in the face of violent attacks from both the west and south and actions by the Resistance.”

Leclerc ordered Tactical Group ‘D,’ commanded by Colonel Louis Dio, to reinforce Billotte. German resistance at Antony collapsed at 4 pm. But further attempts at advance were stymied by shortages of fuel. At about 7 pm, Billotte halted his advance.

An attempt by Putz to push on to the Bourg-la-Reine was rewarded with more death. Yet another German 88mm gun deployed on the intersection of the RN20 and the Avenue Galois hit and destroyed the leading Sherman tank. This was a powerful M4A3(76) nicknamed the Elchingen II which belonged to Lt. Geoffrey de la Bourdonnaye’s 3rd Platoon (2nd Company, 501e RCC). The assistant driver, Private First Class Jean Luc Géronimi, was killed.

It was later discovered that the shell had punched through 60mm of armor. The Elchingen II did not burn but was abandoned. Another Sherman knocked out the 88mm gun. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 1, 124) Putz pulled back his forces.

Moments later a volley of German rocket artillery crashed into the highway. A member of the Resistance information network told the 2e DB that the German battery was located 8,300 meters from Croix de Berny, in the Bois de Meudon. Battlegroup Massu was in that area and was redirected to the site of the firing. The artillery salvos ceased. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 1, 124)

The battle for the Antony-Fresnes-Berny triangle was over. Free French losses were three killed in Antony. Overall losses were eight Free French killed and 42 wounded. Some 70 Germans had been captured.