INTO THE BREACH

By now, Captain Dronne and his 9th Company of Spaniards had pushed on alone, deeper towards Paris. The jubilant population hindered the pace of their progress more than the scattered German forces did.

“One skirmish followed another against a strangely festive backdrop,” Dronne later said. “An enthusiastic crowd flooding in from all sides surrounded our tanks and brought them to a standstill.” (Dronne, loc. 145, 25%)

Then again, the frightful thing happened. German gunfire and mortar blasts tore into the crowd. “I can still see a grinning young girl covered in blood and slumped across one tank… She had taken a burst in the face,” Drone said. “It was an odd battle: when the shooting stopped, the crowds flooded back, only to vanish as the gunfire resumed. Who knows who many of those hotheads paid with their lives for their demented rejoicing.” (Dronne, loc.145-159, 27-32%)

Moments later, Dronne received new orders over the radio: he was to pull back, 600 m south of La Croix de Berny axis. He was enraged. The order “was nonsense,” he said later. “The thing to do was to slip and bypass [the axis].” (Dronne, ibid.) The order likely emanated from Putz’s headquarters and was not reversed despite Dronne’s protests.

Leclerc was south of the Croix de Berny junction, when he saw the returning 9th Company. He recognized it through the recognition of a single man, Private Jose Ortega (alias German Arrúe), who had given him a haircut when the division was in Yorkshire.

“Where’s Dronne?” Leclerc asked Ortega.

Ortega pointed towards his fellow Spaniards returning along the road. Leclerc called over to Dronne’s deputy, Lt. Amado Granell. “Where’s your chief?” he asked.

“El Capitan?—Just back there,” Granell said.

Dronne saw Leclerc standing in the middle of the road with a group of divisional officers. Leclerc was impatiently tapping his cane on the ground. Never a good sign, Dronne knew.

“Dronne, what have you done?” Leclerc said.

Dronne informed the general that had found a gap in the lines but that he had been ordered to pull back. He was now going south to prevent adding to the traffic jam building up at the junction.

“Stupid orders need not be complied with,” Leclerc said. He added: “Make a bee-line for Paris, Get through however you can and strike for the heart of Paris and tell the Parisiens to keep up their morale. Tell them the entire division will be in Paris by tomorrow evening.” (Dronne, loc. 159-172, 32-36% & Mesquida, loc.189)

As the writer William Mortimer Moore said: Only fate could have decided that a Catholic nobleman would hand a bourgeois intellectual and his company of Spanish atheists one of the most important missions of the war. (Moore, Paris ’44)

NIGHT ADVANCE

Dronne recalled that it was just after 7 pm when this interaction happened. He needed an hour to prepare. It was not possible to extract Lt. Vincente Montoya’s section (the equivalent of a US Army platoon) from the fighting at the Croix de Berny junction. The section was left behind.

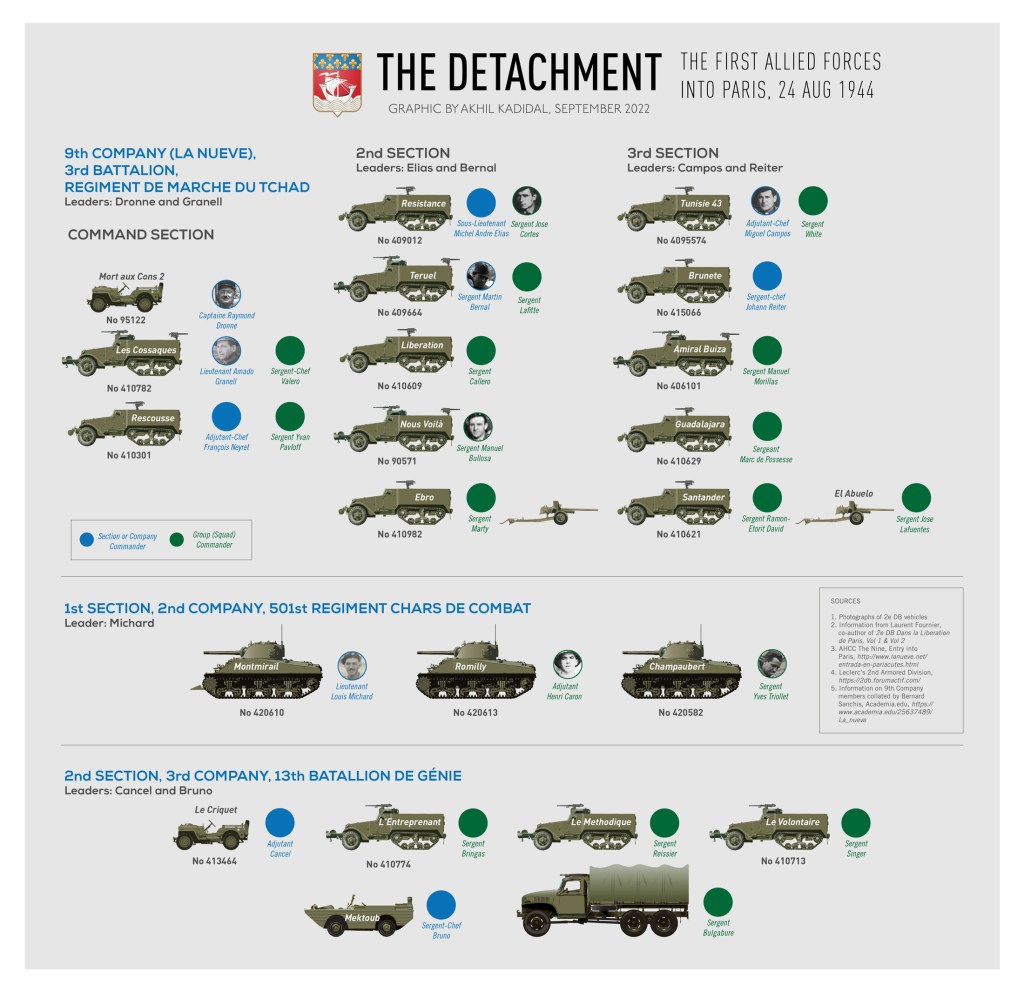

All Dronne had were two sections of his company (the 2nd and the 3rd, comprising about 116 troops and 12 halftracks). To this was added a section of three Sherman tanks (15 men from the 2nd Section, 2nd Company, 501e RCC) under Lt. Louis Michard, a seminarian before the war. Dronne also wrangled the participation of a section of 41 combat engineers (2nd Section/3rd Company) under Chief Warrant Officer Cancel. All together, the task force had about 172 men and 20 vehicles. (Association August 24, 1944 – La Nueve https://www.24-aout-1944.org/la-nueve-en-bref/)

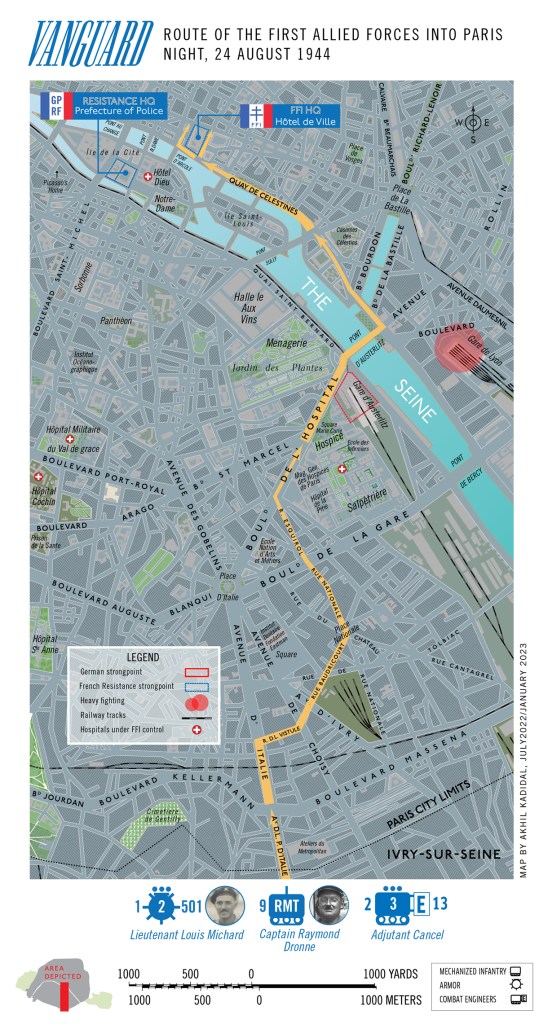

It was about 8 pm. Dronne’s mission was to simply reach Paris. Inwardly, however, he decided that he would make for the Hôtel de Ville, which had been occupied by Rol’s forces. Guided by Georges Chevallier, a Antony native, the unit drove through the side roads of the villages and suburbs of Paris: Haÿ-les-Rosas, Cachan and Arceuil, past the fort of Bicêtre towards the city.

“Everywhere the population rushes our way and gives us an enthusiastic welcome,” Dronne said. “ For us, Free French, whom the official France of Vichy had condemned, this reception of the people of Paris was both our reward and our justification. We didn’t want to show it, but we were moved to tears.” (https://www.24-aout-1944.org/La-journee-du-24-Aout-1944/)

From Bicêtre, it took them nearly half an hour to reach Porte d’Italie, which represented one of the capital’s ancient border posts. It was about 8.45 pm. The city was dark and strangely quiet. The capital had no electricity in the hours of darkness during the occupation.

“Paname!” Dronne exclaimed, recalling the old nickname of Paris. His company erupted into cheers.

Parisiens who heard the column and the cheers and saw the unfamiliar vehicles, the strange shapes of the helmets of the soldiers, first thought the men were Germans.

“The crowd looked at us in astonishment,” Dronne recalled. “A few shouts rang out: ‘The Germans, the German tanks!’ The crowd, worried, backed away and began to disperse and flee. Then other cries were heard: ‘The Americans, they are the Americans!’ The crowd halted their retreat and cautiously began to advance to get a closer look at these strange vehicles and uniforms they did not know.” (https://www.24-aout-1944.org/La-journee-du-24-Aout-1944/)

The surprise turned to euphoria when the crowd learned the detachment was the vanguard of a Free French armored division.

A human swarm covered the task force. “About 30 meters away I can see a tank, immobile, covered in people,” said journalist René Dunan who was at the scene. “In an effort to hold on, people are grasping each other, limbs are intertwined, heads close together. The crowd around the tank wave their arms, scream their lungs out, use any means they can to show their elation. The young soldiers, in khaki uniforms, their American helmets tipped back on their heads, their faces tanned, deep rings around their eyes, are stunned and astonished by the welcome.”

The driver of one of the three Shermans, Sergeant Gaston Eve of the Montmirail, found he and his crew being “kissed on our faces and on our berets as so many people were totally overwhelmed by the madness of the moment. Our blackened faces were soon smeared with lipstick. People were giving us bottles of wine and these were put away in the tank safely. We gave away packets of biscuits, little bits of our survival rations of chocolate and of course we returned the kisses being given us and hugged the people we were fighting for.”

His commander, Lt. Michard, ordered his crew to sound off the tank’s siren, to clear the way.

“I started to tell those on and around the tank that they must get off and those roundabout started pushing and shouting ‘Get off!’ That proved effective and we started to see clearly ahead of us. We departed behind [the tank] Romilly very slowly because the way through was very narrow. Everybody was shouting I don’t know what and waving us goodbye with their hands. We responded and waved away like gladiators going into the arena. What a moment for a soldier to have lived. Such moments live on in the soul ever more, believe me!” Gaston said. (Cobb, 270)

Dronne asked for directions to the Hôtel de Ville. The crowd began to shout out contradictory directions. Dronne’s eye fell on a strange-looking youth sitting on a moped and wearing clothing replete with patches. The youth wore wooden-soled shoes.

The youth shouted out, asking him where Dronne wanted to go. When asked who he was, the young man introduced himself as Lorenian Dikran, an Armenian member of the French resistance. This was full of symbolism for Dronne who recalled the loss of one of his two Armenian soldiers earlier that day: Private Hernozian-Luis.

Dikran agreed to guide the detachment to the Hôtel de Ville. Dronne’s relief was interrupted by the sound of breaking glass. His jeep windshield, which had been folded down on the hood, had cracked – broken by a large girl sitting upon it.

Dronne was stupefied. The girl beamed at him. Dressed in the traditional Alsatian costume of red skirt, black-aproned white blouse and black head-dress, she introduced herself as Jeanne Borchert. She also refused to move.

When the column drove off, it was with Borchert sitting on the hood of the jeep, resembling an elaborate hood ornament. The column moved rapidly along the Avenue d’Italie before turning into smaller streets such as the Rue de la Vistule, Rue Baudricourt, the Rue Nationale, and the Rue Esquirol. The column turned into the boulevard de l’Hôpital, heading towards the Seine.

As the detachment raced by the Gare d’Austerlitz, German forces in the train station opened fire. Ignoring this, the liberators kept going, over the Pont D’Austerlitz. Borchert leapt from the jeep when the column crossed over at the north bank. There was no time for farewells. The column encountered no resistance as it threaded over the Quai Henri IV and the Quai des Celestins towards the Hôtel de Ville.

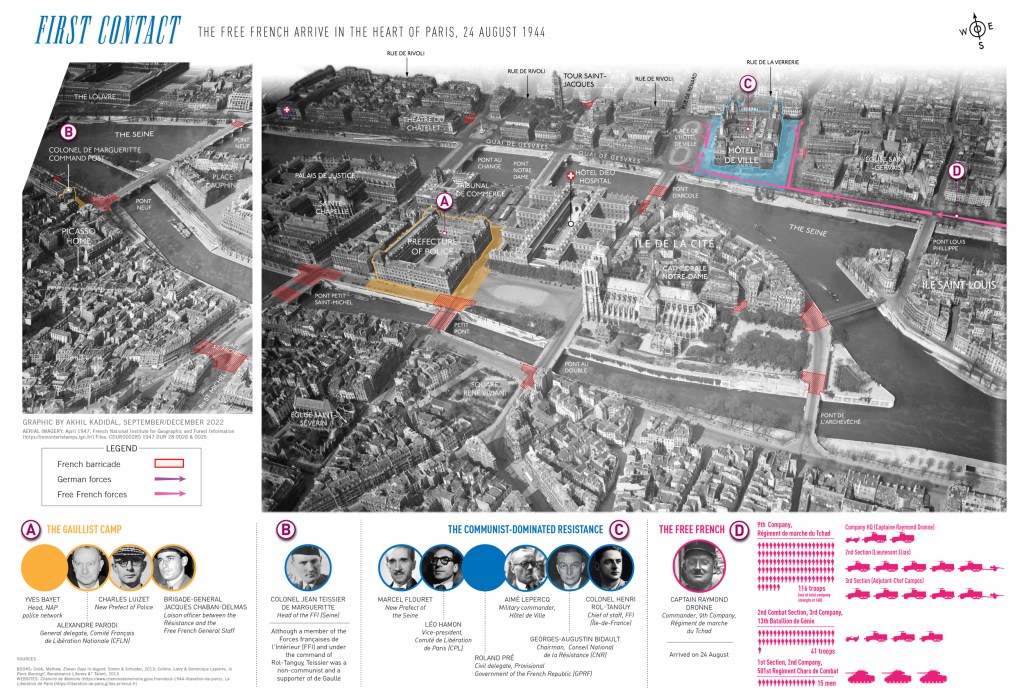

By one account, a team led by Dronne’s deputy, Lieutenant Amado Granell reached city hall several minutes earlier by taking a slightly shorter route. However, the details of this route are unavailable (see Mesquida). Granell was apparently met by Georges Bidault, chairman of the CNR and therefore political head of the French resistance.

Bidault was no wallflower. He had assumed chairmanship of the CNR after Jean Pierre Moulin (the legendary first leader of the French resistance) was captured and killed by the Germans. Bidault had since led the resistance from the turbulent period of the summer of 1943, walking a fine line of approval from the communist diehards of the resistance to the non-communist de Gaulle in Algiers.

Note: Bidault would later become a controversial figure after the war because of his staunch defense of French colonialism. He would emerge as a French patriot who had claimed the right to resist German imperialism but could not then fathom that the colonized peoples of other lands should have a qualm with French imperialism. (see Memories of a Disappointed Man, Stanley Hoffman, The New York Review https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1968/02/01/memoirs-of-a-disappointed-man/)

Bidault was apparently taken aback that the first liberator of Paris was not a Frenchman but a Spaniard.

Some of the late summer light still lingered when Dronne’s detachment reached city hall. Officially, the first halftrack to roar into the plaza was the Guadalajara, comprising a crew made up largely of Extremadurans from the land of Hernando Cortés, Francisco Pizarro and the conquistadors. Next was the halftrack Ebro. Dronne looked up at the Hôtel de Ville’s great clock. It was 9.22 pm.

The column formed a protective circle around the building. A 57 mm anti-tank cannon known as El Abuelo (The Grandfather), was set up on the street near Lt. Michard’s Shermans to deal with German armor.

Out of the thin light, a crowd of joyful Parisiens descended on the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville. Soon the detachment was overwhelmed again by civilians. The French were astonished to hear many of the soldiers speaking French in a Spanish accent. To one Parisian, the sight of the armored halftracks and the three Sherman tanks was “a hundred times more moving than the solemn victory parade of 1919.” (Neiberg, loc. 464.8, Ch. 8, 76%)

Among the onlookers was a young resistant who had spent the last few days fighting at the Prefecture of Police. Jean Dutuord, 24, whose nom de guerre was Commandant Arthur, in homage to the late boy-genius poet, Arthur Rimbaud. Dutuord had run to the Hôtel de Ville from the prefecture after hearing that French tanks had arrived.

He observed that Dronne “was welcomed like a prince, like Napoleon arriving from the island of Elba. He was more than a soldier; he was a symbol. In his person, La France Combattante joined hands with La France Résistante: Free France with slave France. From that moment on, there were no longer two Frances, but a single nation that was in the process of being reborn, that once again was going to be indivisible.” (Richard D.E. Burton, Blood in the City: Violence and Revolution in Paris, 1789–1945, 239)

The crowd swirled around Dronne not to see him, but to touch him, as if to prove to themselves that he was real and not a phantom. Dutourd observed that Dronne never smiled once. His focus on the task appeared total. He and his men stood like minor Gods in comparison to the Zapatista-like FFI, with their ammunition bandoliers slung crosswise across their upper torsos, their battledress, consisting of a mishmash of civilian clothing, “their shirts nearly open to the waist”. (Burton, ibid)

The ovation for Dronne and his men was so shrill that it felt to a journalist from the resistance newspaper, Action, that the windows at the Hôtel de Ville must burst. (Neiberg, ibid) The crowd erupted into the Marseillaise. Together with Granell and his aide, the small, wry Krikor Pirlian, Dronne mounted the stairs towards the entrance of the Hôtel de Ville to meet the political high command of the French resistance.

A radio reporter latched on to Pirlian. “I have in front of me a French soldier,” the reporter said, “a brave guy who has just got here. Tell us, where are you from? Where were you born?”

“Constantinople,” Pirlian said. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, 62%)

Radio journalist Pierre Crénesse, who had spent much of the Prefecture of Police, also appeared at the Hôtel de Ville to check up on a radio set up by his team. That was when he first saw the US-made halftracks and Shermans.

Sprinting into the building, he found a telephone and called his studio. Patch me in live, he said and then made the following report:

Tomorrow morning will be the dawn of a new day for the capital. Tomorrow morning, Paris will be liberated, Paris will have finally rediscovered its true face. Four years of struggle, four years that have been, for many people, years of prison, years of pain, of torture and, for many more, a slow death in the Nazi concentration camps, murder; but that’s all over… For several hours, here in the centre of Paris, in the Cité, we have been living unforgettable moments. …These soldiers of the Leclerc Division and their comrades of the FFI on the place de Hôtel de Ville, machine guns over their shoulders, automatic weapons in their arms, revolvers in their hands, renewing an old acquaintance, seemed to me to symbolise the resurrection of France, the union of the fighting external armies and those of the Interior who have been hunting the Hun for the last five days and who have already liberated the main public buildings in the city, and taken the main strategic points in the city. The vanguard of the Allied army of liberation tells us that, in a few hours, the bulk of the British, American and French troops will be on this place de l’Hôtel de Ville, right in the middle of Paris, and that we will able to hail them, and the last Huns will have been chased from the capital! (Crénesse (1944), p. 29–30)

It is not known if Victoria Kent Siano, a Spanish exile and lawyer, and defender of the lost Second Spanish Republic heard Crénesse or another reporter, for at 9.26 pm the radio in her apartment announced that: “The vehicles of the Leclerc division are arriving, with Spaniards at the wheel.” (Mesquida, loc. 2359, 49%).

Kent, who had lived in Paris since the loss of the Republican Spanish government in 1939, was stunned. In October 1943, she had been sentenced in absentia to 30 years in prison by the ruling Francisco Franco government in Madrid. She had since gone into hiding from the Gestapo under the assumed name of Madam Duval. The last ten months of her life had been spent in an apartment in Boulogne given to her by the Red Cross. Now, she was free.

Words escaped Kent. She buried her face in her hands and cried in disbelief: “Spaniards! Spaniards!” (Mesquida, ibid)

Inside the Hôtel de Ville, Dronne and his companions climbed the main staircase to the grand salon. The captain saw that the central chandelier in the salon was at maximum light. He thought this was “reckless.” (Dronne, loc.193, 51%)

Bidault stood with several lieutenants of the resistance: Marcel Flouret, Lecompte-Boinet (a member of the CNR), Joseph Lainiel (also of the CNR), Georges Marrane of the CPL….

Dronne became self-conscious. When he had started out on his journey towards Paris over two days ago, he had shaved and worn a fresh uniform to look smart for the city. Now, sweat had made his battledress unkempt, his hands and face were stained with vehicle and gun grease. A fine carpet of facial scruff added to his dishevelment. His képi was no longer round at the top as it should be. He had not slept in 48 hours.

The resistance members appeared to be struck by the presence of the soldiers in their US Army-supplied olive drabs. Georges Bidault tried to make a speech but his voice choked up with emotion. He moved to embrace Dronne. The captain protested: “But I’m so dirty, so filthy – it’s been such a long drive!” (Cobb, 271)

Bidault pulled Dronne towards him and said: “My dear captain, in the name of the ununiformed soldiers of France, I embrace you as the first uniformed soldier of France to enter Paris!” (Yvonne Féron, Délivrance de Paris (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1945), 51)

A moment later, a burst of German machine gun fire tore through the big, open windows and smashed into the chandelier. Everyone dove for cover as glass shattered into mist. The troops outside swung into action. A hail of return fire burst from the guns of the halftrack Tunisie, commanded by Chief Warrant Officer Campos.

The crowd in the square had scattered, melting into the darkness. Crénesse and many of the other journalists lingered on as the rest of the Spanish and the French vehicles joined in raking the German position.

When the shooting died down, Rol-Tanguy appeared and sought to elevate the sacrifices of the FFI to that of the army of de Gaulle. Speaking into Crénesse’s handset, he said: “The capital has largely been liberated thanks to the guerrilla tactics carried out by the FFI. Open the road to Paris for the Allied armies, hunt down and destroy the remnants of the German divisions, link up with the Leclerc Division in a common victory – that is the mission that is being accomplished by the FFI of the Ile-de-France and of Paris, simmering with a sacred hatred and patriotism,” he said. (Crénesse (1944), 33-34)

By the time Dronne emerged from the Hôtel, the square was largely devoid of civilians. Aspirant Gaston Cascaye (aka Bacave), a Pied Noir from Algeria who was on Dronne’s headquarters staff, had radioed 2nd Division’s headquarters with the message: “We are at the Hôtel de Ville!”

Two policemen turned up and asked Dronne to accompany them to the Préfecture. Leaving Lt. Granell in command, Dronne and Pirlian drove to the prefecture where the Gaullist resistance awaited: Luizet, Chaban-Delmas and de Gaulle’s representative in the city, Alexandre Parodi. When Luizet asked Dronne if he wanted anything, he answered: “A bath.” (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 658.9, Ch. 10, 62%)

The 13-ton grand bell in the south tower of Notre-Dame which had not run in four years, began to toll. The rings were taken up by the 17-ton “Savoyarde” at the Sacre-Coeur church in distant Montmartre. Soon 150 church bells were ringing across the city.

At the Hotel Meurice, Choltitz and his staff heard them as they ate dinner.

“So, they are here!” Colonel Jay exclaimed.

Seeing the glum looks on the faces of the other members of his staff, von Choltitz said angrily, “What else did you expect? You’ve been sitting here in your little dream world for years. You see nothing but your own pleasant life in Paris… Germany has lost this war, and we have lost it with her.” (Collins & Lapierre, 268)

Von Choltitz went into his office, picked up the telephone and spoke to his superior Speidel and General Walter Model. He held the telephone out of the window.

“Can you hear that?” he asked.

“Yes, I can hear bells,” Speidel replied.

“That’s right. The Franco-American Army has entered Paris,” Choltitz said.

“Ah,” Speidel sighed.

After a short silence, von Choltitz asked for orders. There were none.

“In that case, my dear Speidel, there remains nothing for me to do except to bid you adieu. Take care of my wife, and of my children,’ Choltitz said.

“We will do that, General. We promise you,” Speidel said. (Cobb, 275)

Almost on cue, the electricity flashed on in the city. People turned on every light in their homes and the yellow-white glow swept onto the streets. Dronne left the prefecture and returned to his men at the Hôtel de Ville. Turning down offers of a room, Dronne bedded down in the street outside the Hôtel at around 2 am.

He went to sleep to the sounds of his men singing an old song of the lost army of the Ebro from the Spanish Civil War. (Mesquida, loc.2398, 50%).

¡Ay, Carmela! Ay Carmela!

The Army of the Ebro

Rumba la rumba la rum bam bam!

One night the river passed,

Oh, Carmela, oh, Carmela!

And to the invading troops

Rumba la rumba la rum bam bam!

He gave them a good beating,

Oh, Carmela, oh, Carmela!

PLAN OF ACTION

Back at Croix-de-Berny, Leclerc too was sleeping in the open. Having pulled into a sleep bag set up under a tree by his batman, Sergeant Loustalot, Leclerc tossed and turned.

His thoughts always turned to Dronne and the 9th Company at the Hôtel de Ville, and of de Langlade at the Pont de Sèvres, and of Massu. It had been a difficult day for the division. Seventy-one troops had been killed, 225 were wounded and 21 were missing. Thirty-five divisional tanks, six self-propelled guns and 111 vehicles had been destroyed. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 614) These heavy losses were hardly indicative of procrastination by the division as Gerow and Bradley believed.

As Leclerc tossed, Model was sending a message to Berlin, intended for Hitler: “Given the evolution of the situation” pull out all troops west of Paris to form a new defensive line to the east of the capital. (Cobb, 278) It was not yet apparent to the Germans that the east was being compromised by advancing US army units.

Meanwhile, in the west, at the Sèvres bridgehead, a fracas erupted when a withdrawing German flak unit came upon Massu’s column. At about 1.15 am, an RMT officer, Lt. Postaire, stationed with his platoon on the Avenue Bellevue, about 200 meters north of the bridgehead, heard engine noises.

Several Germans trucks and jeeps, driving without headlights, blundered directly into the Free French position. Fighting erupted at extreme close-quarters. The battle was so confusing that one Moroccan soldier, seeing men preparing a light cannon for operation, prepared to help them — until he realized that they were Germans. (Bergot, loc. 286.7, Ch. 16, 43%)

The battle raged for half an hour, before the German withdrew, leaving behind three vans, three 20mm Flak cannons and several bicycles. Also strewn on the road were 40 dead Germans. Twenty-one other German prisoners were being led off to the rear. (Bergot, ibid)

De Langlade would say that when dawn came “the last 500 meters of the Versailles road on the approach to the Pont de Sèvres were covered in vehicles and dead bodies. (Cobb, ibid)

At around 4 am, Leclerc got up from his bed and went to have a shave in a local barbershop in Antony. The shop was open. A mass of civilians who had stayed beside the troops that night also roused from their sleep. They gathered around Leclerc as he sat in his White Scout car in awe. Orders for the day were issued at 4.30 am.

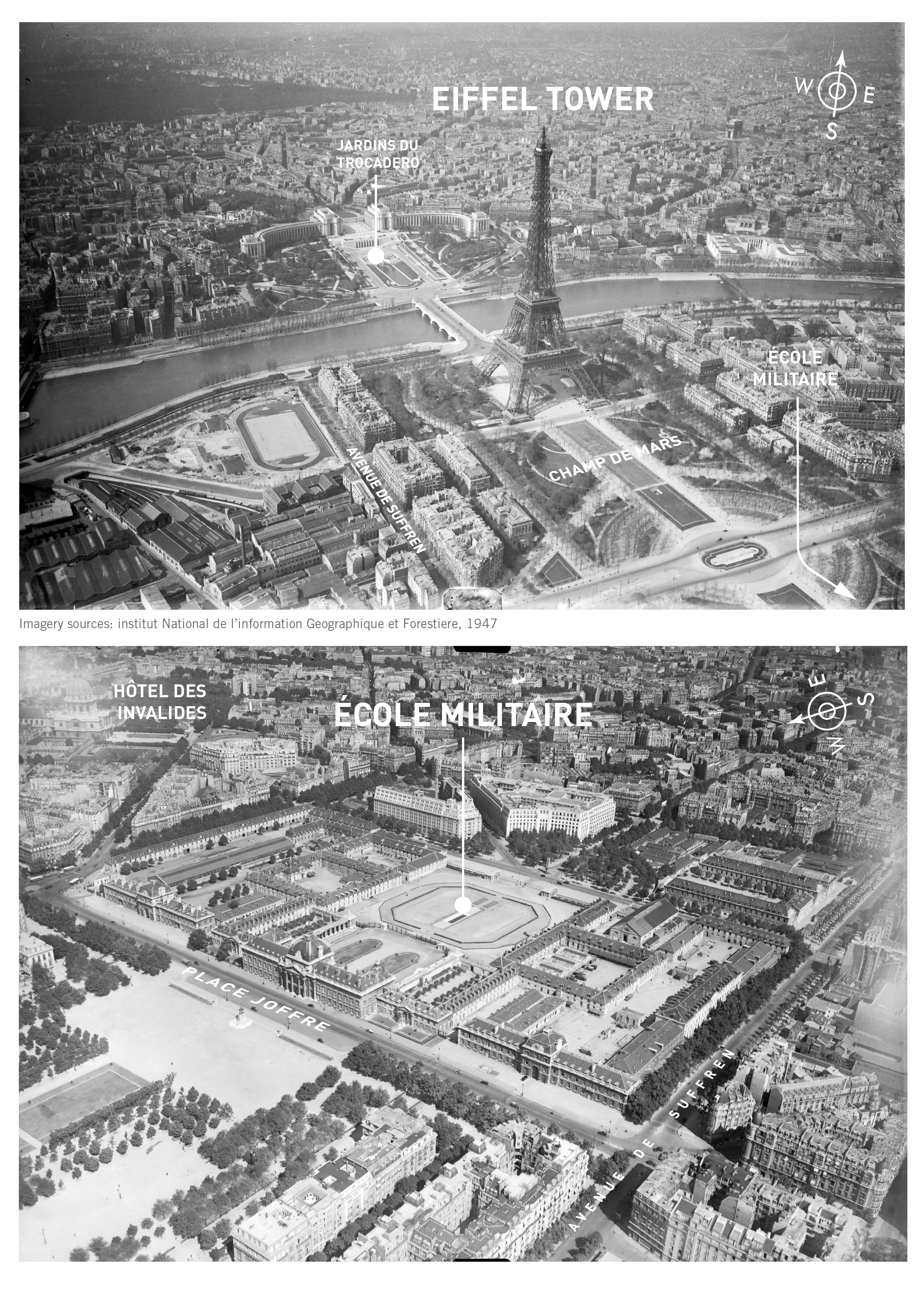

Leclerc’s plan was to attack in four coordinated prongs. The division would secure four key areas: the Place de l’Étoile, the area around the Place de la Concorde, the École Militaire and the Senate building in the Jardin du Luxembourg.

Battlegroups Warabiot and Putz (from Tactical Group ‘V’) had the primary role of securing the heart of Paris: the latin quarter and the primary four arrondissements.

Three of Warabiot’s units: Captain Jacques Branet’s 3rd Company (501e RCC) with 10 Shermans), a detachment of five tanks under Lt. Yves Bricard from the 1st Company (501e RCC) and the mechanized infantry of Captain Marcel Sanmarecelli’s 3rd Company (RMT) were issued orders to secure Paris’ most prestigious road — the Rue de Rivoli where the Hôtel Meurice stood with von Choltitz inside. This detachment also had orders to secure the Place de la Concorde, the Quai du Louvre and the Jardin de Tuileries.

Meanwhile Battlegroup Putz had orders to reach the Seine along the Avenue des Gobelins, the Rue Monge, the Boulevard Saint Germain and the Boulevard Saint Michel. Putz had two detachments for this task: Captain Jacques de Witasse’s 2nd Company (501e RCC) with nearly 17 Sherman tanks and the mechanized infantry of Captain Maurice Sarazac’s 10th Company (RMT). This unit also had orders to clear the Quai des Grands Augustins and the Rue de Seine of German forces.

Putz was to be supported by Leclerc’s Headquarters Protection Squadron under Captain Alain de Boissieu who had one platoon of M3 Stuart light tanks and two platoons of M8 Scott self-propelled howitzers — In all, about 15-16 light tanks. De Boissieu had orders to secure the Boulevard Saint Michel and the Rue de Vaugirard.

Meanwhile, in western Paris, Tactical Group ‘L’ under Colonel de Langlade was to converge on the Place de la Concorde from the Arc de Triomphe at the Étoile and along the Champs Élysées. The advance was to be led by Massu’s battlegroup, followed by Lt-Colonel Minjonnet’s battlegroup.

Meanwhile, Tactical Group ‘D’, until Colonel Louis Dio, was to split into battlegroups commanded by Lt-Colonels Rouvillois and Noiret.

Noiret’s forces were to enter the city from the Porte de Orleans and run along the Boulevard Victor and the Rue Balard. From there, the unit was to seize control of the Seine bridges between the Porte de Versailles and the École Militaire before occupying the Champs de Mars and the Eiffel Tower.

Rouvillois’ forces were to advance along the Avenue du Maine, past La Gare Montparnasse, and through the Boulevard des Invalides, the Palais Bourbon and the Quai d’Orsay.

The divisional reserve, Tactical Group ‘R’, under Colonel Rémy, with reconnaissance troops and tank destroyers was to move around the divisional flanks to mop-up German forces at Trappes and Versailles. Once these areas had been secured, Rémy had orders to rush through the Pont de Sèvres route into Paris to secure the north bank of the Seine to harass Germans retreating through the city.

US forces from the 4th Division, notably Colonel James Luckett’s 12th Infantry Regiment, plus B Company of 4th Combat Engineers Regiment and a company from the 12th Anti-Tank Battalion, were to secure the east bank of the Seine and the city.

Joining the 4,200-odd US Army GIs which comprised this force was a tall, slender New Yorker named Jerome D “Jerry” Salinger.

As a later biographer, Shane Salerno, would write: “Salinger was a privileged, sheltered twenty-five-year-old from Park Avenue who thought war would be an adventure – glamorous, romantic. He imagined himself the protagonist of a Jack London novel and hoped military service would explode the bubble in which he was raised.” (Shields, David & Shane Salerno, Salinger, loc. 24.9, Ch 1, 2%)

Salinger saw war as a means to give himself the pain that he thought was vital to be a writer. Having landed on D-Day with his intelligence unit (the 4th Counter Intelligence Corps), he carried six chapters in his pack of what would become his post-war magnum opus, The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger was on his way to Paris and a fateful meeting with his idol, Ernest Hemingway.

Officially, there was no British military presence in the liberation — except for a unit of Royal Marine commandos. This was ‘X’ Troop from No 30 Commando (also known as No 30 Assault Unit (AU)).

Although a Royal Marine troop was the equivalent of an army infantry platoon (30 men), “Woolforce” as the detachment was called, comprised 75 men with halftracks and two to four armored cars, all under the battalion commander, Lt-Colonel Arthur Woolley. Their mission was to secure key U-boat related intelligence from German Kriegsmarine headquarters and offices in the city.

That night, resistance radio read out an urgent announcement in German: “Achtung! This is the staff of Colonel Rol, commander of the FFI in the Ile-de-France. We have learnt that the German commander in Colombes is going to shoot 10 French hostages. If he carries out his plan, we will shoot 10 German Army soldiers, 10 members of the SS and 10 German women auxiliaries.” (Crénesse, 38)

On the eve of the liberation of the capital, it was clear to the Germans that the French resistance, that army of the shadows, had lost all fear of Nazi oppression. But the imminent arrival of the 2nd Division also meant that it would be the Gaullist uniformed forces that would finally liberate the city and not the resistance as Rol-Tanguy had so desperately had hoped.

THE BATTLE BEGINS

As dawn fell on Paris on 25 August, the 2nd Armored Division, poised at the gateways into the capital, prepared to move out. Violence was almost immediate.

In the west, de Langlade’s Tactical Group ‘L’ prepared to depart the Porte de Sévres area at 7 am, but left behind a detachment to clear out the Renault factory in the area.

A column of Germans tried to break out of the factory. A truck that raced out of the factory was blown to pieces by an M8 Scott. Other trucks appeared out of the smoke – and were raked by Free French fire. Some Germans jumped into the Seine to escape the French but were fished out by the French divisional combat engineers. By the time the fracas ended, the 6th Company of the RMT had 200 prisoners, 15 light vehicles and 20 trucks with supplies. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 705.7, Ch. 7, 70%)

At the same time, in the center, Putz’s battlegroup moved into the Porte de Gentilly and entered the city. The gateway was thick with Parisiens, singing the Marseillaise and throwing flowers. As Billotte stood in his scout car, an apple came flying out towards him. He caught it with both hands. In Sherman No 40 (Douaumont) of the 3rd Company, 501e RCC, Sgt. Marcel Bizien, 23, originally from Brittany, found himself hugging a beautiful brunette. A hail of German bullets smashed into the crowd. The girl slumped in Bizien’s arms. Blood poured from three bullet wounds in her back. (Moore, Paris ‘44, ibid)

At about 7.30 am, Warabiot’s battlegroup entered the city from Porte d’Italie.They were followed by the US 12th Infantry Regiment, led by elements of the US 102nd Cavalry Group. The Americans, being based further south of the city, had started out the day at 6.20 am.

Also, at about 7.30 am, Tactical Group ‘D’ began to advance towards Porte d’Orleans. It would cross the gates a little after 8.30 am. The murky clouds of the 24th were giving way to bright skies. The 25th of August was the feast of Saint Louis, patron saint of France. The French hoped this was an omen of good hope.

A Parisien journalist, Jean Galtier-Boissière, was amazed to see the 2nd Division driving past his front door on Rue Saint-Jacques. “An excited crowd surrounded the French tanks, which were covered in flags and bouquets,” Galtier-Boissière said. “On each tank, on each armoured [sic] car, next to each khaki-clad, red-capped soldier, there were girls, women, kids, and armband-wearing ‘Fifis’. The people on either side applauded, blew kisses, shook hands and shouted to the victors their joy in liberation!” (Cobb, 280)

Leclerc himself entered the city at 9.30 am, to the chorus of World War I veterans singing the victory songs of 1918. (Neiberg, loc. 471.3 ch. 9, 77% & Cobb, 285).

Accompanied by Chaban-Delmas, Leclerc headed for the Gare Montparnasse train station, which he had decided would be his headquarters. He had originally intended to set up his headquarters at Hôtel Crillon but German resistance within Paris had scrapped that plan.

At the Hôtel de Ville, the crowds were back to see the 9th Company. To Dronne’s annoyance, somebody stole the pennant from his jeep’s radio antenna. Meanwhile, gung-ho FFI members tried to convince the 9th Company to attack several German strongpoints which Dronne did not have the manpower to tackle.

However, when two civilians arrived with news that German engineers were planting explosives at the Central Telephone Exchange on the nearby Rue des Archives, Dronne and Granell roused their men for combat. The telephone exchange was a vital communications nexus for the resistance and the Free French across Paris. That would stop if the building was blown up.

Dronne and Granell dispatched the 2nd Section under 2nd Lt Michel Elias to secure the exchange, supported by Michard’s Shermans and Cancel’s engineers.

Two columns are formed: one under Elias and supported by Warrant Officer Henri Caron’s Sherman Romilly. This unit advanced along Rue de Temple. The second column, under Lt. Michard of the Sherman Montmiral, together with Sgt Yves Triolet’s Sherman Champaubert, were backed by a platoon of FFI militia. This second force advanced along the parallel Rue de Archives.

Lt. Elias’s group approached the building. A group of Germans and civilian sympathizers opened fire from a house located on the far side of the exchange. Bullets plunged into Elias’ chest. Sergeant Jose Cortes, who was standing near Elias, was also hit. Both men would pull through after spending months in the hospital.

A fierce firefight erupted. Some two platoons of Germans were holding the exchange and it took French-Spanish over an hour (until 11 am) to secure the building. About a dozen German engineers were killed but 30 surrendered, including their commander, a hulking lieutenant.

Dronne, who had arrived, demanded that the Germans remove the explosives that they had planted. The German lieutenant said that this was against the rules of war. Dronne replied in German that such rules did not apply to non-military installations. The Spanish-French troops watched with growing anger.

When the officer still refused to yield, the irate troops moved to pummel their prisoners. This broke German intransigence. They set to work removing the explosives. Dronne was astonished to see that explosives had been planted everywhere: under the main equipment, behind doors, tables and even on chairs. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 712.3, ch. 7, 71%) In all, about 100 kgs of high explosives were removed. (Cobb, 285). Most of Dronne’s command returned to the Hôtel de Ville after this engagement.

However, one detachment proceeded northwards towards the Place de la République to assist FFI forces holding positions against the Prinz Eugene barracks. Originally built by Napoleon III, the Place de la République had been built over a maze of narrow streets once famous for theaters and anti-government sentiment during the revolutions of 1830 and 1848. The barracks were built to house over 3,000 troops. Its location was intended to facilitate the rapid deployment of troops in the working class neighborhoods of the area.

Now, the barracks held nearly 1,200 German troops, including SS forces and several tanks, including at least two tanks classified as “heavy,” which suggest Tigers. The façade of the barracks was protected by two 75 mm cannons, six 37 mm guns, and an armored car. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 106-8)

FFI militiamen from the Compagnie Saint-Just group, together with two FTP units, had kept the garrison pinned with constant fire but did not have heavy weapons to overrun the barracks. (Cobb, 303). The Compagnie Saint-Just group hailed from the 20th arrondissement and was commanded by the liberal poet, Madeleine Riffaud, who had turned 20 two days before. During the occupation, the group had caused havoc in the city with train sabotage and shootings of German soldiers. (Paula Schwartz, “Partisanes and Gender Politics in Vichy France,” French Historical Studies, Vol 16, No 1 (Spring 1989), 129). The FTP units were led by a 25-year-old medical student named Darcourt.

However, the group’s lack of heavy weapons allowed the Germans to gradually marshall their strength. That previous afternoon, several hundred German troops had counterattacked FFI’s positions across the square, dislodging the militia from several locations.

Warrant Officer Caron climbed out of his tank to help a group of FFI fighters moving towards the place de la République, when a German machine-gun nest hidden in the entrance to the Temple Métro station opened fire. Bullets punched into Caron and several FFI soldiers near him.

Three FFI men, Albert Béal, Henry Kayatti and Marcel Bisiaux, all died. Caron died of his injuries on the following day. (Cobb, 285)

In the west, Tactical Group ‘L’ had broken out of the Sevres bridgehead and was racing towards Arc de Triomphe. Major General Hubertus Aulock (newly promoted to that rank) had been responsible for shoring up the defenses of the Boineberg Line after the departure of the venerable Boineberg-Lengsfeld. It was his anti-tank guns that had delayed the advance of the 2e DB. Now, Aulock’s Kampfgruppe (battlegroup) was down to about 200 men in St. Cloud, backed up by a handful of tanks. Aulock’s own headquarters was at an old chateau in the northeast of Paris.

The breakout of Tactical Group ‘L’ from Sevres threw the remnants of Kampfgruppe Aulock into chaos. The Germans decamped from St Cloud and withdrew into the Bois de Boulogne. As the Free French armor and vehicles surged forward, a German anti-tank gun set up in a bunker at the corner of Rue de Longchamp opened fire briefly before it was obliterated by concentrated Free French fire.

No sooner had Massu’s battlegroup begun to move when it became bogged down again. German anti-aircraft batteries located on the high ground west of Paris (between Buzenval and Garches) sprayed the French battlegroup with fire.

Langlade had the column halted and called up Priest 105 self-propelled howitzers of Squadron Chief Henri Mirambeau’s I Group/40th Regiment d’Artillerie du Nord Africain (RANA). Within minutes, the Priests had pummeled the high ground with 1,200 rounds, the sounds of their guns blasting resembling the gongs of an unrelenting bell — to the stunned joy of local Parisians. (Bergot, loc 293.5, Ch 16)

At around 8.30 am, the men of battlegroup Warabiot reached the Île de la Cité. They were soon greeting the policemen defending the prefecture. They were closely followed by elements of the US 12th Infantry. Much of the US force, however, swept east towards the Place de la Nation and the outlying suburb of Vincennes.

On the western side of Paris, Lt-Colonel Noiret’s battlegroup of 12e Cuirassiers’ Shermans, mechanized infantry from the 2nd Company (RMT) under Captain de Perceval and Spahi armored cars had occupied the Champ de Mars under the Eiffel Tower. Seeing the Nazi swastika flying over the near École Militaire, across the gardens from the Eiffel Tower, a Spahi in an M8 armored car, remarked: “It would only take a 37mm shell to knock that down.”

“Go on, then!” an officer said.

The French were leery of damaging the École Militaire. The defeat of Louis XV in the Seven Years War had interrupted the transition of the École Militaire into the magnificent structure envisaged in the mind of its designer, Ange-Jacques Gabriel.

Gabriel had wanted a structure to outshine the nearby magnificence of the nearby Les Invalides. Still, spread out over a space of 103,552 square meters, the École Militaire represented a formidable defensive point. The Germans, backed by milice collaborators had packed the windows with sandbags and like, at the Fresnes prison, had set up anti-tank guns to cover entry points.

The Spahi fired his puny 37mm cannon. The round missed. Like a roused nest of hornets, the École garrison unleashed their weapons on the Free French detachment.

Soldiers and civilians alike scrambled for cover among the Champ de Mars’ hedge-lined walkways as punishing fire crashed into metal, earth, wood and flesh. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc.716.2, Ch 7. 71%) An attempt by the French to pull back drew more heavy fire. For the next four hours, the Free French here would be pinned by defenders of the École.

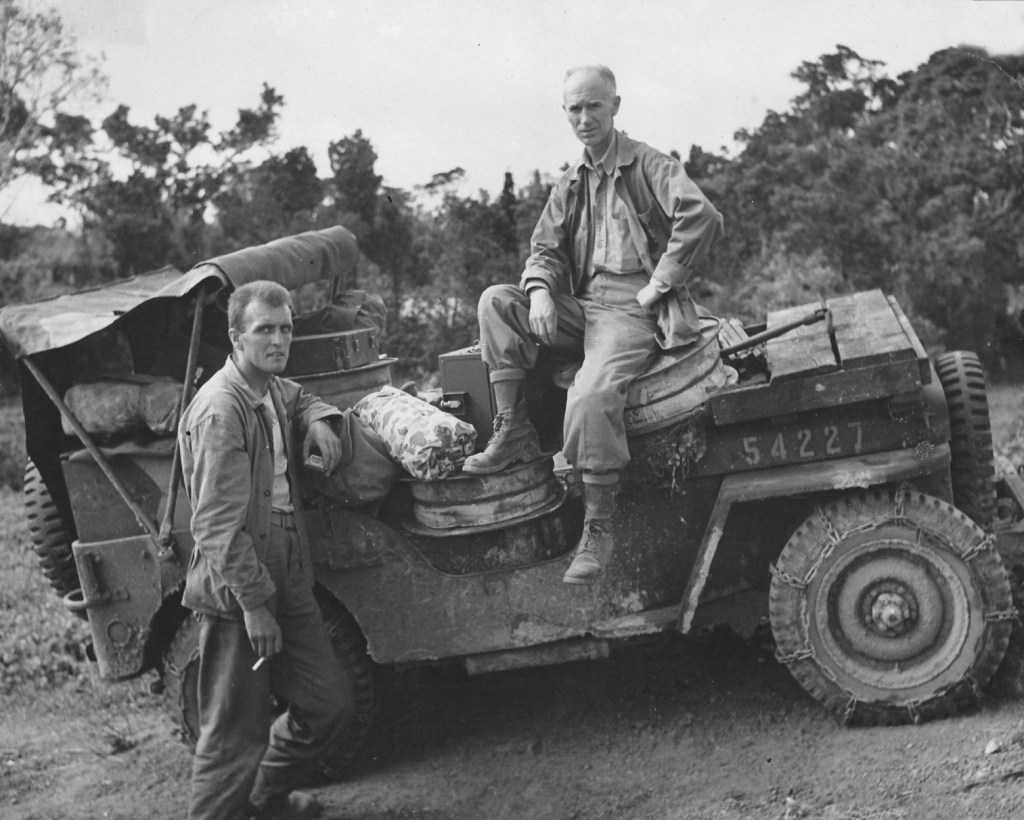

In parts of the city less affected by the fighting and where the citizenry had time and opportunity to exchange news, a rumor spread that de Gaulle would be in the city by midday to assume control of the French government. War correspondents attempted to capture the collective euphoria. For Ernie Pyle, possibly the greatest American correspondent of the war, who had seen the fantastic sights of the D-Day invasion and the gruesome battles inland, the scenes of Paris were so outlandish that he later conceded that he had trouble putting them down in words.

“I was not alone in this feeling, for I heard a dozen other correspondents say the same thing,” Pyle wrote. “It may be that this was because we have been so unused, for so long, to anything bright.” (Pyle, Brave Men, 484).

Free French tanks roared through Parisian streets at high speeds, carrying all manner of flotsam. Then there was the nonchalance of the French population who clogged the streets en masse amid German fire.

“I noticed one tank commander, with goggles, smoking a cigar, and another soldier in a truck playing a flute for his own amusement,” Pyle wrote. “There also were a good many pet dogs riding into the battle on top of tanks and trucks. Amidst this fantastic Paris-ward battle traffic were people pushing baby carriages full of belongings, walking with suitcases, and riding bicycles so heavily loaded with gear that if they were to haul them down they had to have help to lift them upright. And in the midst of it all was a tandem bicycle ridden by a man and a beautiful woman, both in bright blue shorts, just as though they were holidaying, which undoubtedly they were.” (Pyle, 487)

Sergeant J D Salinger wrote that Parisians held their babies up for the Americans to kiss. You stand on the hood of your jeep and “take a leak on it and it wouldn’t matter; it would be okay.” Anything you did was fine. (Shields & Salerno, Loc. 202, Ch 3, 17%)

BBC Correspondent Robert Reid described the scenes of liberation as “one of those emotional experiences which come rarely to any man.”

We were now driving between solid walls of Parisians, a cheering, weeping, waving crowd of men, women and children, the tears coursing down many of their cheeks as they reached up and grabbed our hands and sobbed ‘Merci, merci’, almost pulling us from our seats to hug us and kiss us. Whenever we had to pull up for a moment we were swamped and smothered in embraces and a torrent of French. Small boys hung perilously on to our mudguards, girls tried to scramble up on the hoods of the jeeps; a young mother pressed through the crowd to hold up her newborn baby to me to kiss its head as though asking for blessing. As those good folk wrung our hands and men and women kissed our cheeks, our eyes grew misty and we swallowed hard and couldn’t talk much because of this wave of emotion which engulfed everybody that day of deliverance. No human being could have remained unmoved and I saw many fighting men weep unashamedly that memorable afternoon. (Jeremy A Crang, General De Gaulle Under Sniper Fire In Notre Dame Cathedral, 26 August 1944: Robert Reid’s Bbc Commentary, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television (2007), 27:3, 391–406)

Private Irwin Shaw, a member of the US Army Photo Service with the US 12th Infantry Regiment and a postwar novelist-playwright, would say that August 25 was “the day the war should have ended.” (Blumenson, Liberation, 156). Another American, the historian S L A Marshall, was handed 67 bottles of champagne by joyful Parisians. Jeeps and tanks were covered in flowers. (Neiberg, loc. 471.3, Ch. 9, 77%)

Pyle’s jeep was swamped with human traffic. “ Instantly we were swarmed over and hugged and kissed and torn at. Everybody, even beautiful girls, insisted on kissing you on both cheeks. Somehow I got started kissing babies that were held up by their parents, and for a while I looked like a baby-kissing politician going down the street. The fact that I hadn’t shaved for days, and was gray-bearded as well as bald-headed, made no difference,” Pyle wrote.

“Finally some Frenchman told us there were still snipers shooting, so we put our steel helmets back on. The people certainly looked well fed and well dressed. The streets were lined with green trees and modern buildings. All the stores were closed in holiday. Bicycles were so thick I have an idea there must have been plenty of accidents that day, with tanks and jeeps overrunning the populace.” (Pyle, 483).

One US GI recalled that the city was “fifteen solid miles of cheering, deliriously happy people waiting to shake your hand, to kiss you, to shower you with food and wine.”

But not all was gaiety. Paris remained snared in the cycle of life and death. A battlegroup from the Panzer Lehr Division had been ordered to fight its way to Choltitz. Led by Captain Hennecke, the battlegroup left Le Bourget in the morning.

It found itself being slowed down by barricade after barricade. Finally, it was ambushed by resistance forces. Molotov cocktails turned open-topped halftracks and soft-skinned trucks into death traps. By the early afternoon, Kampfgruppe Hennecke was heading back to Le Bourget, having failed to break through.

A schoolteacher in the suburb of Pantin described the situation: “A German column of about 60 vehicles, including 10 tanks, moves towards Paris; it drives along the side of the school towards the Porte de la Villette. Half an hour later, it turns up again, heading back to Le Bourget. There is gunfire; some bullets hit the front of the school.” (Ritgen (1995), 197-8 & Cobb, 285)

One of the Germans in the detachment was Dr Hans Herrmann, a surgeon. “We were fired upon from windows and we could never see the enemy…The feeling was strange. One would hear a round whistle through the air and not know from where it came.” (Cobb, ibid)

By 10 am, most of the Free French 2nd Division was within the city. At the Hôtel Meurice, von Choltitz went with Colonel Jay on a last jaunt through the Jardin des Tuileries to inspect some defensive positions.

Jay recalled there groups of soldiers moved around, armed with machine guns, crouched behind sandbags or other defenses. Some troops were shooting at FFI fighters on the other side of the Seine. On the opposite bank of the river von Choltitz and Jay saw Allied tanks “driving up and down.” German snipers shot at the tanks without effect. (Cobb, 284)

These were likely tanks from Rouvillois’ battlegroup which had captured the Invalides despite the German strongpoint at the École Militaire. Rouvillois’ smaller detachments move toward the Quai d’Orsay and its ministerial offices.

Also on the move were men of Colonel Billote’s Tactical Group ‘V’, headed toward their vital mission into the heart of the city: capturing von Choltitz’s headquarters at the Hôtel Meurice. At his new headquarters in the billiard room of the Préfecture de Police, Billotte was advised by Parodi and Chaban to first ask von Choltitz to surrender. (Cobb, 288).

It is telling that Billotte did not consult with the communist resistance about this plan of action. In his letter, Billotte gave von Choltitz just thirty minutes to surrender. The most forward troops of Battlegroup Warabiot were already on the Rue de Rivoli, en-route to the Hotel.

“Should you decide to continue a combat that has no military justification, I will pursue that fight until your complete extermination,” Billotte said, signing himself as a “General,” to give the letter gravitas. (Cobb, ibid)

The diminutive Lieutenant-Colonel Jean Fanneau de la Horie was given the job of delivering the letter to Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul general — at his office on Rue d’Anjou — which was behind “enemy lines” in a manner of speaking. Two M8 armored cars, one carrying de la Horie, raced through the streets. They found Rue d’Anjou resplendent with French, British and American flags and with a huge banner, reading “Welcome.”

Nordling, who was recovering from an angina, gave the letter to a trusted associate, a German Abwehr agent named Emil “Bobby” Bender, for delivery to von Choltitz. Bender’s attempt to personally deliver the letter to von Choltitz at the Hotel Meurice was thwarted. He was halted by a patrol of arrogant German sailors on the Rue Saint-Honoré. When Bender explained their mission, a naval officer replied: “In the Kriegsmarine we don’t know what a white flag looks like.”

Bender was allowed to go into the Hôtel Crillon nearby to telephone the Hôtel Meurice. He reached the cold and stiff Lieutenant Count Dankwart von Arnim, the German commander’s 25-year-old Ordnance Officer. Von Arnim said there was no question of the letter being accepted.

Choltitz reportedly told von Arnim, “I don’t accept ultimatums.” (Collins & Lapierre, 294)

According to Dansette (1946), Bender told de la Horie that as long as von Choltitz was allowed to make a symbolic “last stand”, he would surrender without much of a fight (373). Billotte ordered his men to attack the Hôtel Meurice.