CAPTURING CHOLTITZ

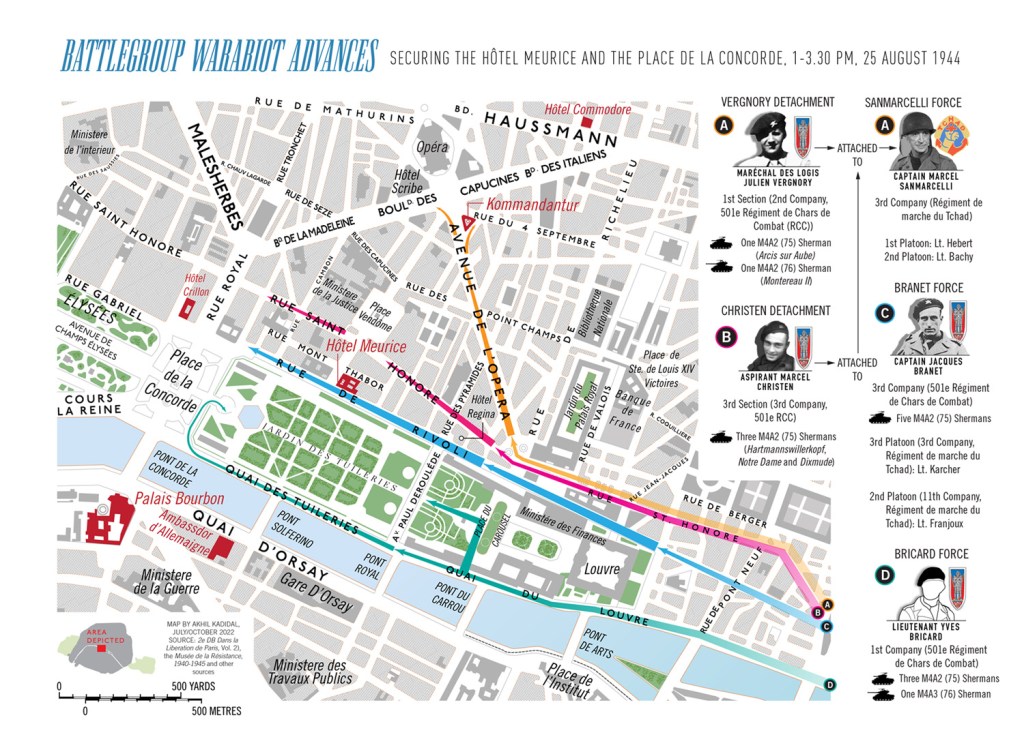

Billotte’s orders were to seize the Hôtel Meurice in the quickest time possible while simultaneously clearing German forces from the Jardin des Tuileries and the Place de la Concorde.

Captain Jacques Branet, commander of the 3rd Company of the 501e RCC was assigned the job. He had two sections (platoons) of infantry from the Régiment de marche du Tchad to storm the hotel in a frontal assault. This included a platoon from the 11th Company under Lt. Jacques Franjoux and a platoon under Lt. Henri Karcher of the 3rd Platoon of Captain Marcel Sanmaracelli’s 3rd Company (RMT). A single platoon of Spahis under Lt. Vézy were also present as were several bands of FFI militia.

Branet’s also had five M4A2 Shermans to cover the infantry. The remaining platoons of Captain Sanmaracelli’s 3rd Company (RMT) were to capture the German Kommandantur (offices of the German military command of occupied France) near the Opera House. Sanmaracelli was reinforced by a detachment of Shermans under Sgt. Julien Vergnory of 1st Platoon (2nd Company, 501e RCC). This tank force would reach the Kommandantur via the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

Meanwhile, three Sherman tanks of Aspirant Marcel Christsen’s 3rd Platoon (of 3/501e RCC) were to secure the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré behind the hotel.

A fourth force of five Sherman tanks under Lt. Bricard of the 1st Company, 501e RCC plus two platoons of infantry from the 3rd Company (RMT) were to destroy German forces in the Jardin des Tuileries and along the north bank of the Seine. Bricard and Branet’s orders also included securing the Place de la Concorde.

Meanwhile, the first Free French units had reached the Arc de Triomphe on the Place de Étoile, nearly 2,000 meters northwest from the Place de la Concorde.

A pillbox on the Rue de Presbourg opened fire on infantry from the 5th Company (RMT). The company was under the temporary command of Lt Paul Gauffre, replacing Captain Langlois who had been wounded in the legs on the previous day. Shermans from the 3rd Section (12e RCA) attacked the pillbox. A Sherman named Perthois fired a high explosive directly into the pillbox’s gun slit. The explosion not only destroyed the pillbox but also the glass front of a novelty shop adjacent to the pillbox. (Bergot, 150. Bergot wrote that the tank responsible was the Bourgogne. However, this Sherman was destroyed on 13 August in Normandy. The tank’s replacement was the Perthois)

Branet, meanwhile, reported starting his mini-campaign at 1.15 pm along the Rue de Rivoli. Lt. Franjoux’s platoon had barely passed the Place des Pyramides when a German machine gun opened fire from on the balcony of a hotel. Four men were hit.

Karcher’s platoon swept up the Rue de Rivoli, clearing all adjacent streets with grenades. Branet ordered his tanks to move ahead of the infantry. As the Shermans thundered towards the hotel, an old 1940-era French Renault R-35 under German command pivoted from a side street onto the Rue de Rivoli and scuttled away from the Free French. At the front of Branet’s force was Sergeant Pierre Laigle’s Sherman Villers-Cotterets. (Bergot, 158)

Sgt. Laigle ordered his gunner to hit the R-35. The Sherman’s cannon barked. The entire street appeared to reverberate as the 75mm shell blazed towards the hapless R-35. The round missed. But moments later, the R-35 blew up. Based on interpretations of the photographs of the tank, the historian Laurent Fournier said it is likely that the tank was destroyed by bazooka-wielding RMT infantry. (Correspondence with author)

The force of the 75mm shell impacting the ground shattered the window panes of the Meurice dining room.

Choltitz, who was at lunch, solemnly finished his meal. He stood up and said: “Gentleman, our last combat has begun. May God protect you all. I hope the survivors may fall into the hands of regular troops and not those of the population.”

This last statement revealed the German horror of a vengeful populace no longer under their control. Already, the incidents of private justice had erupted across the city – with FFI and ordinary citizens conducting acts of reprisal against cut-off German forces and collaborators, even those merely suspected of being complicit with the German regime.

Choltitz began dictating a last letter to his confidant of the last few days, Raoul Nordling. He observed a Sherman gracefully swinging its cannon at the hotel. The head of the tank commander, wearing a black beret, bobbed in the open hatch.

Cholitz wondered if the man was an American or a Frenchman. Whoever he was, he “was not taking this fight very seriously if he was leaving his turret open,” Choltitz thought. (Collins & Lapierre, 301)

A grenade fell onto the Sherman from the roof of a building next to the Hotel – thrown by a contingent of German sailors under Lt-Commander Harry Leithold. It hit the black-bereted head of the tank commander, Lt. Albert Bénard, and slid into the turret. A moment later, a sharp explosion sent shrapnel tearing into Bénard’s body from his waist to his forehead. The stricken tank, ironically named the Mort-Homme (Dead Man), erupted into flames.

The gun-loader, Sgt. Jacques Diot and the gunner, François Campani, were also wounded. Despite their wounds, Diot and Bénard hauled themselves out of the stricken tank and tumbled onto the road. Campani, found himself ejected from the turret by the force of the flames.

Lt-Commander Leithold told his men not to fire on the flaming figures of the Frenchmen rolling on the ground. (Collins & Lapierre, 301)

Campani was pulled to cover by the accompanying French infantry who smothered the flames eating his overalls. He would regain consciousness in a hospital with a bad burn wound on the head. All around him were German wounded in beds while French wounded were propped up against walls. This enraged him. Shoving past a doctor and a nurse trying to sedate him, he pushed over many of the beds with Germans in them. He rushed outside the hospital in shock – and came face-to face with a German officer, a Lüger in his hand.

Seeing a rifle propped up next to a wounded FFI militiaman, Campani grabbed the gun and shot the German officer in the head.

Campani ran to the Rue de Rivoli, convinced that he was the sole survivor of the Mort-Homme. But he wasn’t. All of the crew had survived. Upon seeing that his friends were alive, Campani said that he fell to his knees and started to cry like a “madeleine.”

“So, for me, the liberation of Paris was that. I was 25 years old. I left my hair and my eyebrows there and for a while I was a Yul Brynner look-alike,” he added. (account by his grandson, Jean-François Campani, https://www.chars-francais.net/2015/index.php/classement-individuel/m-4-sherman?task=view&id=987)

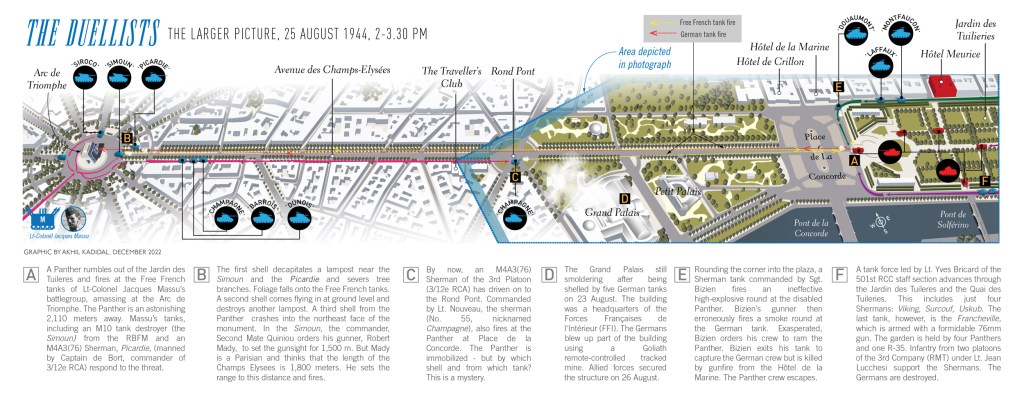

At the other end of the Champs-Elysees, Battlegroup Massu had gathered at the Arc de Triomphe in strength. It was about 2.30 pm. Langlade arrived with Major Mirambeau. The two men approached the Tomb of the unknown soldier. As they saluted, a shell from the Champs-Élysées screamed over their heads, intended for a French tricolor that had just been hoisted. A second round struck the side of Arc, scattering stone fragments near the officers.

Massu and his men scrambled to see where the shooting was coming from. Then they saw it: a single Panther tank rumbling out of the front of the distant Jardin de Tuillers, 2,000 meters away. The Panther took up station on the Place de la Concorde. Massu ran for his field telephone to summon M10 Wolverine tank destroyers.

Meanwhile, back on the Rue de Rivoli, Lt-Commander Leithold was ashen to see the rest of the Shermans moving past the Hôtel Meurice towards the Place de la Concorde, where they would come across the flanks of the Panther.

Leithold tried to signal the Panther’s commander but the tank crew was busy firing at the Free French cloistering around the Arc de Triomphe. (Collins & Lapierrer, 301-302) By now Massu had summoned a tank destroyer from the RBFM named the Simoun. On foot, the RBFM platoon commander, Naval Lt. Durville directed the Simoun to a firing site on the eastern side of the Place de l’Étoile.

German machinegun bullets tore into the low trees above the tank destroyers, bringing down branches onto the Simoun’s open turret and atop a powerful Sherman M4A3 (76) (No 56 Picardie), manned by Captain de Bort, commander of the 3rd Squadron, 12e Régiment de Chasseurs de Afrique (RCA). The Panther fired three more shells which missed their targets and flew towards the Bois de Boulogne. The Simoun began a long-distance duel with the Panther.

A third tank, a M4A3 nicknamed Champagne, commanded by Aspirant Jean-Pierre Nouveau of the 3rd Section (12e RCA), rumbled down towards the Rond Point on the Champs Élysées. Like the Picardie, the Champagne was armed with a formidable 76mm gun. Reaching the Rond Pont, Nouveau prepared to fire.

“Vautravert,” he called to his gunner. “Six hundred meters away, drift 2, an armor-piercing one! Fire!” (Bergot, loc. 305, Ch. 16, 46%)

The Sherman’s powerful cannon boomed. Almost simultaneously, the Simoun also fired. A cannon round struck the Panther, destroying a track and immobilizing the tank. It is unclear which French tank was responsible for the damage.

At the same time, Branet’s tank detachment began to round the corner into the Place de la Concorde. In the vanguard was Sergeant Pierre Laigle’s Villers-Cotterêts and another Sherman (No 40, nicknamed Douaumont), under the command of the red-headed sergeant from Brittany, Marcel Bizien. Despite his youth, Bizien was a hardened veteran of the North African campaign.

Machinegun fire from the Hotel de la Marine ricocheted all over the turret of the Sherman Villers-Cotterêts. Rounds plunged into Sergeant Laigle as he stood in his turret’s open hatch. He slumped forward over the turret, dead.

Bizien’s Douaumont rumbled into the square to find itself confronting the Panther which had taken up station near the Obelisk. The German tank was less than 200 meters away. Bizen ordered his crew to fire. To his consternation, his loader slipped a high-explosive shell into the gun breech. The round smacked into the Panther without causing damage. Alerted to the threat on its right, the Panther’s turret began to swivel in the direction of the Douaumont.

Bizien’s gunner had no armor-piercing rounds and so he loaded an even more ineffective smoke round. By now, the Panther was just 30 yards away. Bizen ordered his driver, Sgt. Jorge Campillo (a Chilean), to ram the Panther. The Douaumont lurched forward with a roar of its Ford V8 engine. It smashed into the Panther’s right flank in a jarring clatter of metal. The Panther was unable to rotate its turret.

Sgt. Bizien clambered out of his turret to take the Germans captive. The smoke swirled around him. To Bizien’s frustration he found the Panther empty. The Germans had fled into Jardin des Tuileries. As Bizien returned to the Douaumont, a German sniper atop the Hotel de Marine opened fire. The bullet plowed into Bizien’s head. He collapsed on the turret, dead.

By a strange coincidence, 10 months later, the crew of the Douaumont II were on the Munich highway in Germany. Their tank had broken down. As they labored to get the tank onto a carrier for transport to the workshop, they called on a German POW passing by to help. The POW was wearing panzer crew overalls.

When they began chatting with the German they were astounded to learn that he had been the driver of the German Panther on the Place de la Concorde. (https://www.chars-francais.net/2015/index.php/classement-individuel/m-4-sherman?task=view&id=845)

In the Jardin des Tuileries and the Quai des Tuileries, Lt. Bricard’s force of four Shermans (Viking, Uskub, Francheville and Surcouf) found themselves in a confrontation with four Panther tanks and one Renault R-35. In the fracas, one Sherman had its rear deck blown apart.

The surviving Shermans destroyed other vehicles on the Rue de Castiglione and parallel streets. The Shermans also raked the windows of the hotels held by the Germans with the fire. The Hôtel Continental (now the Hôtel Westin) was targeted until its facade was disfigured, its windows blown out.

On the Rue de Rivoli, M4A2 Laffaux was among those doing the shooting. Outraged at the destruction of their comrades in the 1st Section, the crew of the Laffaux had gone berserk, firing all but the last 12 of their 90 cannon rounds. The surviving German tanks in the garden had been wiped out but Laffaux was still on a rampage. Branet had to reign in the crew.

“Stop that firing,” Branet snapped over the radio. “You are shooting up the most beautiful square in the world.” (Collins & Lapierre, 305)

Branet and Free French infantry prepared for the final assault on the Meurice. Machine gun fire made the approaches to the hotel entrance dangerous. Lt. Franjoux recalled that the machine gun at the Hôtel de la Marine, some 300 meters beyond the Meurice, was a problem.

“As we crossed the rue de Rivoli; the Tuileries’ side was completely bare and offered no shelter,” Franjoux said. He added that his platoon merged with Lt. Kercher’s unit to become one unit.

“We continue our progress by suffering some losses by grenades thrown from windows of the street. Protected by a man armed with a submachine gun, I arrived with the lieutenant of the 1st Battalion [Lt. Kercher] in front of the hotel door,” Franjoux said in his after-action report. (La Musee de la Resistance)

Among the assaulters was Captain Branet. His exuberance to be at the fore of the advance was perhaps driven by a secondary motive. He was in love with one of Rochambelles, Anne-Marie Davion, one of the group’s prettiest ambulance drivers. Davion was also married – to a member of the resistance. Branet had promised to get her a helmet to serve as the hood ornament of her ambulance. (Hampton, Ch. 4, 41% & Ch. 5, 83%). He appeared to have his sights on a helmet belonging to the German general staff.

The French captain could almost taste the glory of capturing the Gross Paris staff. His dream evaporated when a grenade landed nearby and exploded. Branet saw the world go white. His ears sang. He fell to his knees, blood oozing from wounds in his back and sides. Two infantrymen near him were also wounded.

Branet’s driver called for medics. At that moment, Lt. Franjoux appeared on the scene and looked almost overjoyed to see Branet incapacitated: “Not so clever are you, Captain?” he said, smiling. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 743.2, Ch. 7, 73%) Before Branet was evacuated, he ordered his driver to secure a helmet for Davion. (Hampton, Ch. 4, 41%)

Note: Branet and Davion would marry after the war, in July 1946 – three months after Davion divorced her husband.

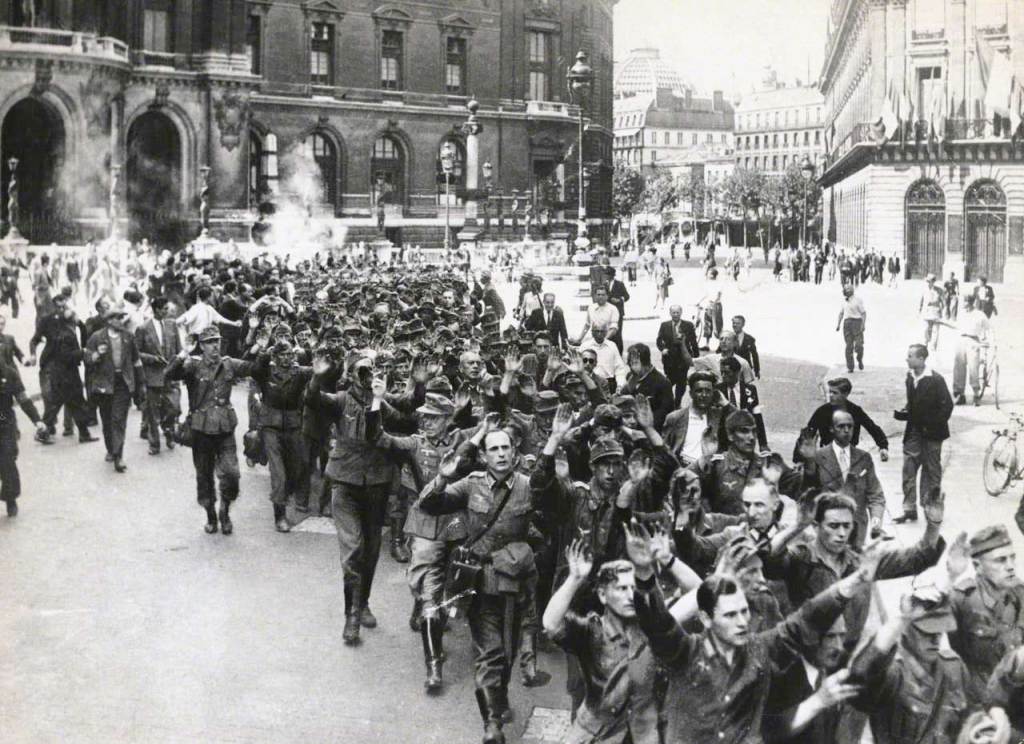

The Free French infantry flooded into the hotel with guns firing. Franjoux was among the first inside. “The hall was dark,” he said. “Private Gutière, from my section, shot down a German on the stairs. Sergeant Brieuce threw a smoke grenade which [hit and] knocked out a German officer with his hands in the air. A soldier from the 1st Battalion who spoke German summoned the officer to call his comrades. About thirty officers and about sixty men come out with raised hands.”

Seeing an official portrait of Hitler on a wall, the Free French infantry riddled it with gunfire.

“Where is the general?” Karcher demanded.

“He is upstairs on the sixth floor,” replied a German officer with his hands raised. Leaving Franjoux in charge of the prisoners, Karcher sprinted upstairs with his men. (La Musee de la Resistance)

In Room 213, General Choltitz was in a state of paralysis. Colonel Jay proposed surrender if the fracas below was caused by Free French troops and not the FFI. Moments later, Lt. Karcher burst into the room.

Von Choltitz found his would-be captor unimpressive – a Frenchman in a donated American uniform combined with French insignia. The General would later describe Karcher as “a haggard and excited looking civilian.”

Behind von Choltitz stood Colonels Unger, Jay and Dr Eckelmann.

Choltitz wrote later that “the civil pointed his weapon at me and asked after several attempts, ‘Sprechen deutsch?’”

“Undoubtedly better than you,” von Choltitz responded. (Dietrich von Choltitz, Brennt Paris? Adolph Hitler (Frankfurt/Main: R. D. Fischer Verlag, 2014), 91)

Moments later, an equally unimpressive-looking character appeared: the diminutive Lt-Colonel de la Horie, with a pistol in his hands. Lt Colonel de la Horie saluted.

Von Choltitz, a little pale, sat upright at his desk, his arms crossed. “I wish that we are treated like soldiers,” he said stiffly. (The Musee de la Resistance)

Lt Colonel de la Horie ignored the statement. “Mon general, are you ready to cease combat?” he asked in French.

“Yes, I am ready,” von Choltitz replied. (Choltitz, 91)

For the French, the elimination of the metaphorical King from the board represented a win. Reality, however, would prove otherwise.

La Horie asked von Choltitz to follow him out of the hotel’s backdoor via a service staircase. Outside, an unruly crowd of civilians had gathered on the narrow Rue du Mont Thabor. It was about 3 pm. Fearing that the crowd would overwhelm the soldiers and their captivates, de la Horie said: “Gentlemen, please keep one step behind me!”

Choltitz could have walked into captivity. Instead, he ambled forward with his hands up. This engorged the rage of the French crowd. The mob began to hurl expletives. When von Choltitz felt his arms dropping, the general’s orderly, Corporal Mayer, whispered to him: “High, higher, General. If you don’t keep them up, they’ll kill you.” (Collins & Lapierre, 311)

Someone in the crowd snatched von Choltitz’s valise which broke, the contents tumbling onto the sidewalk in a ragtag heap. Choltitz watched as his spare pair of general’s breeches, with their distinctive red lampassen down the outside seams, emerged from within the crowd, and progressed deeper into the human masses like some crowdsurfer.

Anticipating problems, Billotte arrived with his White Scout Car, which was more suitable for transporting Choltitz than a jeep. Men shouted and women spat on von Choltitz. To the Prussian general’s astonishment, a woman in a Red Cross uniform appeared and walked alongside him, to shield him from the crowd. Choltitz was moved.

When they reached Billotte’s scout car, von Choltitz embraced the woman. “Madame, comme Jeanne d’Arc (Madam, you are Jean of Arc),” he said. (von Choltitz, 91)

Billotte studied von Choltitz: “He was a large man, around fifty years old, with as sportive and soldierly a demeanor as one could have; although obviously suffering from the heat. … So this was the devil who had fought so vigorously in Normandy,” he thought. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 738.7, Ch. 7, 73%)

Choltitz sat in one of the two seats in the Scout Car, facing the small map table, Billotte recalled. Then, painfully politely, the German general asked if Colonel Jay could also sit in the car. Billotte agreed but added that the only place available was the floor under a table. Both Jay and von Choltitz accepted gratefully. The elegant Jay sat as best he could, with the feets of both Cholitz and Billotte resting on his thighs.

The car drove to Billotte’s headquarters at the Prefecture of Police, where Leclerc was waiting with Major General Barton of the US 4th Infantry Division and Chaban-Delmas.

During the drive, Billotte said to von Choltitz: “I quite understand the reasons why you would have refused my ultimatum. I suppose that you were threatened by the SS. I imagine equally, from what I’ve heard, that your family in Baden-Baden is in a hostage situation and that they would be treated savagely by Hitler if you had not given combat. That said, I quite understand that you could only carry out a baroud d’honneur (gallant last stand). On the other hand, and without yet knowing the number, I know I’ve lost too many of my men. We are therefore placed in the situation envisaged in the second part of my ultimatum, continuing combat until the total destruction of your forces. What can you propose to prevent me from pursuing this course?”

Choltitz became red faced. “Monsieur le Général,” he began, oblivious to the fact that he was talking only to a colonel. “What you say to me is not fair. I have done a lot for Paris. If you knew the orders I had from the Führer–”

“–Right,” said Billotte. “Well, if you think you’ve done so much for Paris, you had best continue in that role and complete your good work by accepting the surrender conditions which will be imposed upon you and by collaborating — it is now your turn — with our officers in seeing that the remaining centers of resistance cease fire immediately.” (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 738.7, ch. 7, 73%)

Choltitz did not respond.

Billotte’s annoyance was not unjustified. Had Boineberg-Lengsfeld or the cadre of anti-Nazi commanders remained in charge of the city, there likely would have been lesser fighting in the capital.

At the Prefecture, von Choltitz was led to the billiards room. Choltitz later recalled that he found himself in a “salle in front of a large number of officers.” (Choltitz, 254) Among the officers were Guillebon, Girard, a Lieutenant de Dampierre, Chaban-Delmas and the gaullist resistance police officer, Charles Luizet. Leclerc was also there, standing solemnly behind a table. An interpreter, Captain Betz, stood nearby.

Choltitz observed that Leclerc wore a waist-length US combat jacket (an “Ike” jacket) with scarcely any insignia. The French general had ‘Francofied’ the uniform by wearing a tie and collar pin. Also present was Major General Raymond Barton, commander of the US 4th Infantry Division.

Barton was in a foul mood. He had wanted to coordinate the actions of his division together with the 2e DB in Paris. But it had taken some effort to find out where Leclerc was. The French general was certainly not his HQ at the Gare Montparnasse. Finally, Barton had been told that his French counterpart was at the Prefecture of Police.

When Barton arrived, Leclerc was having lunch. The Frenchman appeared visibly annoyed at being interrupted. Without inviting Barton to join him for lunch, Leclerc suggested that Barton go to the Montparnasse station.

Barton was hungry, and now he was also annoyed by Leclerc’s standoffish attitude. “’I’m not in Paris because I wanted to be here but because I was ordered to be here,” he snapped to Leclerc.

Leclerc shrugged. “We’re both soldiers,” he said.

When eventually Barton drove to the train station, he found that Gerow had arrived and had set about trying to take over the administration of Paris. Ideally, von Choltitz should have also been driven to the train station for his official surrender. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 617-618)

Choltitz offered Leclerc his hand. Leclerc refused. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 675.2, ch. 10, 64%)

Leclerc asked von Choltitz why he had not accepted his letter.

“I will not accept letters before the fight is over,” Choltitz responded. (Choltitz, 92-93) The two men sat down to inspect the surrender document that had been prepared:

Act of Surrender concluded between the Divisional General Leclerc, commanding the French Forces of Paris and General von Choltitz, Military Commander of the German Forces in the Paris Region.

THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF THE FRENCH REPUBLIC

All the articles here below apply to the units of the Wehrmacht throughout the command of General von Choltitz.

(1) Immediate orders will be issued to the commanders of the strong-points to cease fire and fly the white flag: arms will be collected and troops will be mustered without arms in the open, there to await orders. The arms will be intact.

(2) The order of battle, including mobile units and depots of materials throughout the command, will be handed over. The depots will be handed over intact with their books.

(3) A list of the destruction to works and depots.

(4) As many German staff officers as there are strong-points or garrisons will be sent to General Leclerc’s headquarters.

(5) The conditions in which the personnel of the Wehrmacht will be evacuated will be arranged by General Leclerc’s staff.

(6) Once these articles have been signed and the orders transmitted, members of the Wehrmacht who continue to fight will no longer enjoy the protection of the laws of war.

Paris, 25 August 1944

French accounts of the scene describe von Choltitz becoming visibly uncomfortable. In his memoirs, however, von Choltitz said: “We followed the paragraphs one after the other. Such a document was not, in my view, necessary. It was not as though there would be a capitulation before the end of combat; my headquarters had been taken by the enemy and I was a prisoner along with my staff. This verbiage changed nothing, nor the real situation in so far as it affected myself and my aides. On the other hand the document did address those strongpoints still holding out.” (See Moore, Paris ‘44 and Choltitz, 249)

Choltitz also disagreed with the sixth point of the document. There might be German troops traversing through Paris not subject to his command. It would be ludicrous therefore to expect that they too capitulate.

Leclerc amended the point to: “Nevertheless, the case of any German soldiers in or crossing Paris who are not under the General’s command will be fairly examined.” (Robert Aron, France Reborn: The History of the Liberation (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1964), 291)

As the generals discussed the points of surrender, men, women and children continued to die in the battlezone.