Since the finale of the WWII TV show “Masters of the Air” aired weeks ago, hundreds of media articles have emerged, talking about the “true stories” behind the show. Most are incomplete, repetitive. The following piece will try to provide a historical context to the events portrayed in the show, accompanied by the usual raft of custom infographics.

Please be advised that the following contains spoilers.

Some of the greatest war stories ever told are of units on the brink of destruction and among them, in the European theater of war in World War II, is the tale of the American 100th Bomb Group. The group’s story is now the subject of a new TV drama produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks as a follow-on to their critically acclaimed Band of Brothers (1998) and The Pacific (2010), in what could be the final salvo of their World War II trilogy.

Assembled stateside in June 1942 and shipped out to England in February 1943, the 100th Bomb Group was part of a massive military experiment: the first daylight strategic bombing campaign of an adversary.

This placed it dead center in an unforgiving war fought at 25,000 feet, at temperatures of -50 Fahrenheit against a Nazi foe with some of the finest technology and combat veterans that could be mustered. The Nazis had declared “Total War” (Der Totale Krieg) in February 1943, a state of being meant to achieve victory in the war in the shortest time space by enhancing home front activities and combat operations. Facing such an enemy, the 100th, as an ill-disciplined unit with cavalier officers, became ill-fated and subject to such bloodletting that it became known as “The Bloody Hundredth.”

Masters of the Air (2024), supposedly based on the Donald L Miller history of the same name, tries to be a soaring finale to the Spielbergian view of the American WWII experience, the “good war”: decency versus barbarism, can-do initiative versus clumsy totalitarianism.

Origins

The 100th was a core member of the England-based American 8th Air Force (the “Mighty Eighth”) which tried to blast the German war machine off the face of the map. The Eighth’s “ships,” as the men called their Boeing B-17 heavy bombers, represented a view of American masculinity: strong, rugged, resplendent with gleaming Plexiglas, bristling with guns, an extension of the old west, and decorated with all manner of squadron heraldry and artwork, primarily Disney cartoon characters or gaudy pinup girls. In fact, the rule of thumb appeared to be: the gaudier the art, the better.

Some men called their machines, “flying porcupines,” but the US Army Air Force (USAAF) preferred the name, “The Flying Fortress.” The B-17’s raiding partner was the Consolidated B-24 Liberator which gets zero screen time in the TV series.

Across B-17 and B-24 bases, the “ops” always began the same: a fleet of jeeps racing towards planes assigned on the mission, men with anxious faces and shouting voices. A green flare launched from the control tower indicating to men in the cigar-shaped hulks that the moment had come. They were to return once again to the lion’s den where some had gone before and had never lived to tell the tale.

In the spring of 1943, when the 100th appeared on the scene, 8th Air Force was a neophytic army, the US Army Air Force’s (USAAF’s) newest progeny. Its inception on 1 February 1942 had come with a twin caveat: sustain the primary American air effort against Nazi Germany and validate the controversial pre-war concept of strategic bombing.

The Eighth’s leading elements arrived in England shortly after – a scant two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

In comparison to tactical air power, tested on the battlefields of France in the latter part of World War I, strategic air warfare was a new idea. As US historians put it: “Strategic bombing bears the same relationship to tactical bombing as a cow does to the pail of milk. To deny immediate aid and comfort to the enemy, tactical considerations dictate upsetting the bucket. To ensure eventual starvation, the strategic move is to kill the cow.”

The 8th Air Force’s singular objective was to incapacitate Germany by air before the first American troops set foot on occupied Europe. This, it did not achieve, but without the Eighth’s presence, Allied victory over Nazi Germany would have been more costly and less assured. The Eighth’s war was spread across an unprecedented and bloody 39 months, battle-torn and replete with massive losses. The Eighth suffered more deaths than the entire US Marine Corps (USMC) did during the Pacific campaign, Miller writes.

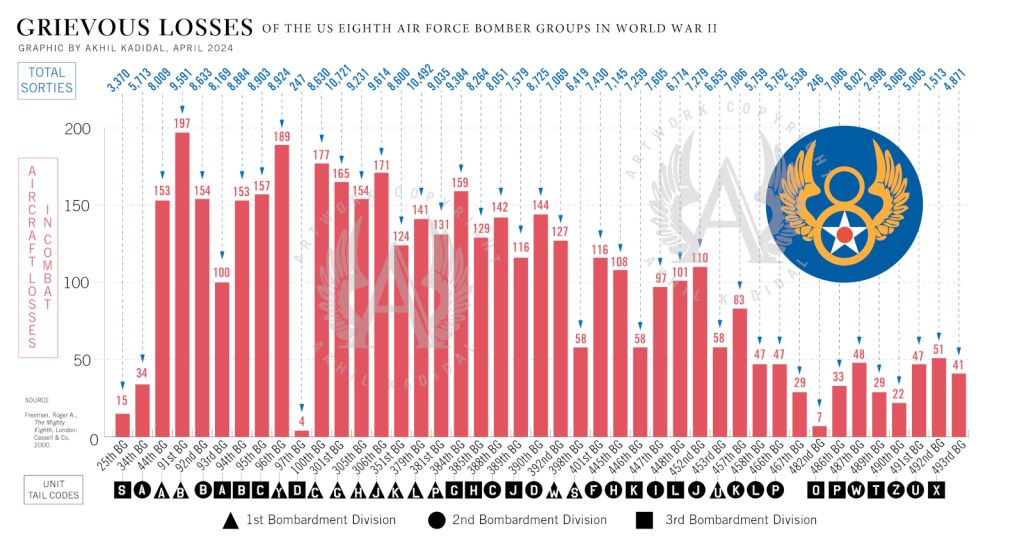

The statistics are sobering. The Eighth lost at least 6,333 aircraft of all kinds in combat during the war, 26,000 men killed in action, 18,000 men wounded and 28,000 men captured. The 100th Bomb Group alone lost 177 bombers in combat and suffered 1,756 casualties. (See Roger Freeman’s 8th Air Force War Diary, Eighth Air Force History & Statistical summary of Eighth Air Force operations European theater, 17 Aug. 1942 – 8 May 1945, HQ Eighth Air Force, June 1945) The USMC’s total fatalities in World War II were between 19,733 and 24,511 personnel. (USMC University/National WWII Museum)

All this makes for gripping drama. Telling this story requires a cast of hundreds of key historical figures. Spielberg and crew cut down the casting numbers by focusing on the 100th.

But even when Masters concentrates on a modest collection of 37 bomber crews, a smattering of American Red Cross girls and English locals, most of the aircrew characters blend into each other, becoming indistinguishable, the effect worsened by a litany of half-mumbled names: Blakley, Brady, Bubbles, Crank, Hambone, Red, Winks… The problem is compounded with how little screen time many characters who could and should be important are given. We get to know nothing about these people; what compels them, what their lives in the pre-war era were, how they were shaped or what they want to shape up to be.

Even the third and fourth wartime commanding officers of the 100th are glossed over so quickly that we are scarcely made aware of what ailed them. The series requires at least two viewings to figure who is who, apart from the central characters of pilots Gale “Buck” Cleven and John “Bucky” Egan, navigator Harry “Croz” Crosby and a maverick B-17 pilot, Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal, who hold the narrative together.

The British actor, Callum Turner, appears to have been cast because he somewhat resembles “Bucky” Egan but the lean Austin Butler (aka Elvis) is no physical match for “Buck” Cleven. A young Orson Welles would have been. Their on-screen charm, however, could match the charisma of the real-life Egan and Cleven, as literature describes them to us:

“They, more than any other of our leaders, had the real Air Corps raunch, their hats cocked on the backs of their heads,” Harry Crosby wrote in his 1993 memoir, A Wing and a Prayer. “Egan’s white fleece-lined jacket is his trademark…. Bucky Cleven and Bucky Egan are like what their men saw in the movie I Wanted Wings…The Two Buckeys [even] talk like Hollywood.”

Crosby, NY: Open Road, p. 40

Unimpressive Start

Much of what happens in Masters of the Air closely follows Crosby’s memories that the series should have been named A Wing and a Prayer, a title perhaps too cliched and straight of ‘80s daytime television to suit 21st century filmmaking. If Masters of the Air tries to avoid anything, it is cliché. Some of it stumbles off the script.

Scenes from the first episode of Masters also appear reminiscent of the 1990 film, Memphis Belle, starring Mathew Modine and a motley young crew of ‘90s B-listers. Memphis Belle, itself replete with clichés, is in many ways a narratively superior work with strong characterizations.

Within the first six minutes of Masters, we are treated to a scene showing “Buck” Egan diving his B-17 Flying Fortress to put out an engine fire, much as Modine and crew do. Twenty minutes later, the landing gear of a B-17 (No 071) in Masters will not lower, forcing the crew to conduct a wheels-up landing. Again, reminiscent of Memphis Belle. But as Crosby narrates in his book, the crash-landing of 071 actually happened. Then after 45 minutes into the episode, Cleven’s B-17 nearly finds itself in collision with other forts in thick clouds – again, vintage Memphis Belle.

Where the series succeeds is in its portrayal of neophytic, gung-ho warriors confronting an enemy at the top of its game. By 25 June 1943, when the 100th flew its first combat mission against Germany (an abortive operation against Nazi submarine pens at Bremen) the German Luftwaffe (air force) was a battle-hardened outfit with 45 months of combat experience.

This superiority in arms manifested itself. During the Bremen mission, the 100th lost three bombers and 30 men from its low-flying squadron in a matter of minutes to a swarm of Luftwaffe fighters. The scene is visceral, even if the CGI is unconvincing: B-17s blowing up with ease to German fighters flying nimble yet haggard, strange.

When, after the slaughter, on the jeep ride to debriefing, an ashen Cleven asks Egan: “Why didn’t you tell me…it was like that?”

Egan suggests that such experiences are beyond description but that everyone “had seen it now” – as though they had gazed upon the darkness of a monstrous creature.

“I don’t know what I saw,” Gale responds after a moment. With that one can begin to fathom the horror that US air crews confronted in that summer of 1943.

Masters’ production values are astonishing. Movie prop makers BGI Supplies Limited supplied two entire B-17 replica aircraft, with the innards of a third reproduced for historical authenticity but reportedly with clever, hidden panels that could be pulled out for camera positioning.

Even the acting is largely stellar, barring some distracting, forced American accents by a majority British-Irish cast. Especially appalling is Barry Keoghan, playing B-17 pilot Lt. Pete Biddick as though he was a Brooklyn thug. In actuality, Biddick was a soft-spoken, even-tempered Wisconsian.

In the first four episodes, the series lives in the moment, without pushing the narrative to examine what everything is leading up to, until it feels like Masters is pulling its punches – unlike Band of Brothers and The Pacific.

There are no discussions about the course of the war, none about battle-fatigue or even the nature of their enemy. There is no certainly no introspection on why the 100th was taking such heavy losses. The answer was sloppy leadership by most of the senior officers in the group, including Cleven and Egan, Crosby suggests in his memoir, while sparing Major Jack Kidd (the group air XO).

Where the aerial combat scenes thrill, the ground sequences fizzle. If the men are not shown guzzling liquor, horsing-around, and chasing women (which undoubtedly happened), they are singing paeans of praise for each other. The downtime dialogue limps. In one episode, while ravenously eyeing an American Red Cross girl in the group’s mess hall, a bombardier says: “They really need to put her into mass production”. (see below)

It is a curious line — ripped straight out of 1946’s The Best Years of Our Lives, a staggeringly honest film about returning WWII servicemen struggling to reintegrate into society.

In that film (an admitted favorite of Steven Spielberg’s), this line is spoken by Captain Fred Derry (also an 8th Air Force bombardier) as honest praise of 28-year-old Peggy Stephenson (played by the late, great Teresa Wright). Peggy is an embodiment of 1940s American womanhood, sassy, whip-smart and a picture of homefront resolve. There is little lecherousness in Derry’s tone.

During the second episode, the 100th’s upper crust unnecessarily picks a fight with their British counterparts about who is fighting the better war. An unconvincing boxing match ensues.

Another cringe-worthy moment is the depiction of a briefing for the 100th’s Mission No 8 (24 July 1943). The new unit commander, Colonel Neil “Chick” Harding (played by James Murray), behaves like a master of ceremonies at a magic show.

When told that their target is submarine pens at Trondheim, Norway, the group officers hoot, holler and hurray – which, coming as it does, not 30 days after the stunning losses over Bremen, is a bit puzzling. According to Crosby, the euphoria actually happened. But by being faithful to Crosby’s memories, the series’ writers closed themselves off to opportunities for more relevant scenes and dialogue to capture reality beyond one man’s memory.

For instance, US bomber crews across southeastern England were by this stage acutely aware that their lifespan could be measured in weeks, if not days. German fighters were taking such a toll on the bombers that two-thirds of crews taking part in a typical raid could expect to be killed, wounded or captured. In June 1943, 86 whole bomber crews were lost across the 8th Air Force – 38.3% of all crews available. (Williamson Murray, Strategy for Defeat, Table XXXIV, pg. 176)

Losses escalated after the Germans understood how to effectively destroy the heavily protected B-17s.

The then-commander of the 8th Air Force, Major General Ira C Eaker (who never appears in Masters, despite his real-life interactions with the 100th) realized that the USAAF had overlooked a critical flaw in the B-17’s defensive arcs of fire. The bomber’s frontal armament was weak. The early model B-17E/F and the Liberator B-24D versions had just a single, forward-firing machine-gun in the Plexiglas nose. In many cases, this gun was removed as it interfered with the operations of the bombardier.

Two junior Luftwaffe pilots, George Peter-Eder and Egon Mayer of III/Jagdgeschwader 2 (translating to Third Group, 2nd Fighter Wing) had noticed this. They evolved the head-on attack – a maneuver in which the German fighter flew head-on towards the bomber, opening fire at the last possible moment before breaking to avoid a collision. If successful, the barrage of gunfire would kill the bomber pilots before tearing through the length of the bomber, cutting to pieces anything in its path.

Experienced Luftwaffe pilots would wait until the bomber filled their gunsights, usually at a distance of 1,000 ft, before firing a short two-second burst with their cannons and rolling over and swooping down in an abschwung (Split-S) to avoid collision and gunner fire.

This is shown in vivid detail midway through the series during a 10 October 1943 attack on the German city of Munster (Mission No 35 for the 100th Bomb Group). By this stage of the war, the group had already lost 32 B-17s in combat and 322 crewmen. They had few illusions about their chances of survival. Massed German fighters attacked the group head-on.

The dangers of collision were terrific. Attacking pilots had to reckon with closing speeds of over 700 feet per second between their aircraft and the quarry. The attackers took up position two miles ahead of the Fortress stream. Initially, the B-17s appeared in their gunsights as small dots, but as the distances closed, the dots grew into lumps, and then gradually formed to give off the first contours of the bomber. The bomber would then begin to grow with alarming alacrity before mushrooming in the front of the entire windshield.

Often the attacker had only a two second interval to open fire before breaking to avoid collision, hoping that he would miss the Fortress’s looming tail fin as he went past.

A bombardier recalled one such attack: “They came in from 10, 12, 2 o’ clock, guns winking, then just a few feet away, would break below, some of the hot-shots actually doing a roll as they went. You could feel the shells hitting the ship, but you were holding formation and apart from a quick burst from the forward guns, there wasn’t a damn thing you could do about it.” (Michael Wright, ed., Reader’s Digest Illustrated History to World War II (London: Readers’ Digest, 1989), 268)

American bomber crews came to dread the so-called “twelve o’clock high” attack.

As losses escalated, tempers were taut across the 8th Air Force. During one briefing on 14 October 1943, the commanding officer of a group attempted to lighten the mood of his men. “It’s a tough job,” he said, “but I know you can do it. Good luck, good hunting and good bombing.”

“And goodbye!” a forlorn gunner added from the rear. (Wright, ed., p. 269-270) Such striking, unexpected exchanges are lacking in Masters.

Change of tone

In episode five, the tone of the show begins to change. After being briefed to attack the German city of Munster, a group pilot, Lt. Charles Cruickshank (played by the British actor, Matt Gavan), broaches the disturbing matter of accidentally bombing civilians: “It’s a Sunday…you saw [during the briefing] how close that cathedral is to the MPI [main point of impact]. We are hitting it right when everyone’s coming out of Mass. There are a lot of people [in that area]”.

“They are all part of it,” retorts a crewman.

Cruikshank attempts to respond but “Bucky” Egan cuts him off. “It’s a war…This won’t end till we hit ‘em where it hurts,” Egan says, suggesting that this covered killing women and children.

When Cruikshank protests that this won’t bring back the men that the group has lost, Egan browbeats him into silence by pulling rank.

If this is a subtle effort by the writers to show Egan’s weaknesses as a leader, it is well couched. Or perhaps, it is simply inspired by the reservations of real-life bomber crewmen.

Munster was a strategically important city. It was a military town, with extensive facilities for infantry, cavalry and artillery units. There was also an ordnance depot, and amongst other things, an army recruiting headquarters, covering the district. The city also had an industrial reputation, with a factory manufacturing light and heavy wing parts for the Messerschmitt aircraft company. (Ian Hawkins, The Munster Raid: Bloody Skies over Germany (Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Aero, 1990). Yet, none of these targets became the specific targets for the bombers.

At the 95th Bomb Group, the briefing officer told his men:

Your target for today, gentlemen, is Munster. It is a vital rail junction between Germany’s northern coastal ports and the heavy industries and munitions plants of the Ruhr Valley. Through these marshaling yards, day and night, roll hundreds of tons of arms and war materials produced in the Ruhr…destined for points North, West and East. However, unlike all previous [raids]… today will be different …very different…because today you will hit the center of the city, the homes of the working population of those marshaling yards. You will disrupt their lives so completely that their morale will be seriously affected and their will to work and fight…substantially reduced.

Hawkings, pg. 83

It was the first time that the USAAF had endorsed an attack that could directly impact the civilian masses. A navigator, Captain Ellis Scripture, was so appalled that he approached his commanding officer (CO) to opt out of the raid.

The CO was livid.

“Look Captain,” the CO said, “this is war… We’re in an all-out fight. The Germans have been killing innocent people all over Europe for years. We’re here to beat the hell out of them…and we’re going to do it.” (Hawkins, pg. 85)

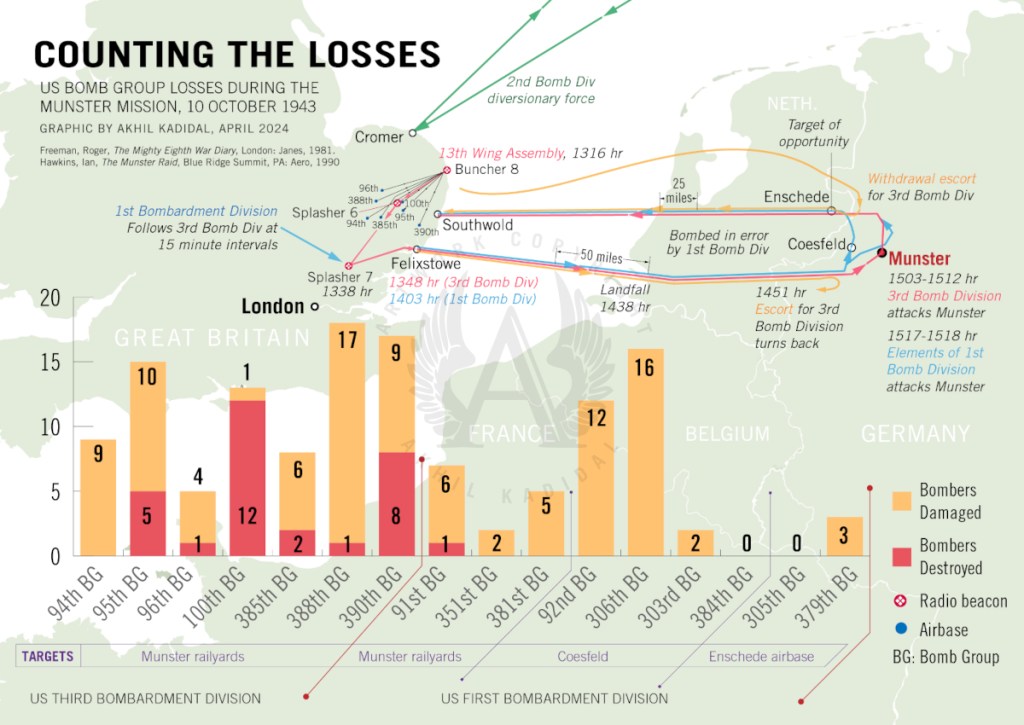

The plan for Munster was to have 133 B-17’s from the 8th Air Force’s 3rd Bombardment Division hit the city. Within the 3rd Division was the 13th Bomb Wing. The wing’s 53 Fortresses from the 95th, 100th and 390th Bomb Groups were to lead the attack on Munster, while 40 bombers apiece from the 45th and the 4th Bomb Wings followed.

A deficit of long-range tanks for American escort fighters at the time meant that the bombers could not be protected along the full length of the mission. The range of Allied fighters at the time was limited.

The British Supermarine Spitfire, used in the early USAAF operations in 1942 was a formidable dogfighter, but was handicapped by a combat radius of 175 miles. The major American fighter of the time; the beefy Republic P-47C Thunderbolt was a good aircraft, but it lacked the turning maneuverability of the German thoroughbreds and also hobbled by a radius of action of 230 miles. If a 108-gallon centerline drop tank was available, it could extend the range to 340-375 km, but the pilots hated them. They reduced performance and had a tendency to blow up when hit.

Another important fighter, the Lockheed P-38G Lightning was in limited service with the US 78th Fighter Group at Duxford, north of London, but the aircraft was unsuited for fighting above 20,000 ft, where the action was. The P-38G/H had a modest range of 475 miles but were not yet ready for operations at the time of the Munster mission.

Despite the limitations of their aircraft, US fighter pilots tried to protect the bombers for as long as they could. In the series, however, US and Allied fighters appear to have little to no role. In one episode, seeing P-47 Thunderbolts heading home after finishing half of their fuel, “Bucky” Egan sardonically comments that the fighters had got the bombers through the English Channel at least. In reality, the Thunderbolts could range up to eastern Holland.

For the Munster mission, a heavy fighter escort of 216 American P-47 Thunderbolts had been arranged, but due to the limited supply of drop tanks, only relay flights of Thunderbolts were possible. One group would escort the bombers only to the initial point (IP), near Dorsten inside the German border, while another group would rendezvous with the returning bombers at a relay point (RP) to provide withdrawal cover back to England. In the large gaps of unprotected airspace to the target and back, the bombers were at the mercy of the Luftwaffe.

The bomber crews watched as the “little friends” took up positions alongside their massed formation, and all was quiet until they reached the IP.

As the Thunderbolts departed, a formidable array of German aircraft appeared. Two hundred and forty German fighters, mostly Messerschmitt Me109s and Focke-Wulf Fw190s but also twin-engined Messerschmitt Me110Gs, Me210s and Junkers Ju88s appeared. Attacking from all sides, the Luftwaffe blazed away for 45 minutes.

Amongst the attackers were 35 Me110 rocket-carriers from Zerstörergeschwader 26 (ZG26, Destroyer Wing 26). Approaching the bombers from behind in formation, the Me110s fired in unison. At least 75 Gr.21 rockets sped towards the Fortresses.

One of the first B-17s to be caught in the salvo was flown by John Winant Jr, son of the US Ambassador to Britain. Winant, a member of the 390th Bomb Group was flying a B-17 in the last element of low flight and had just bombed Münster when a Gr.21 rocket arched towards his B-17 nicknamed “Tech Supply”. The rocket exploded a few feet away, spewing the bomber with its concentrated charge of shrapnel and high-explosive. Six parachutes blossomed in quick succession as the bomber fatally arched earthwards before crashing ten miles northwest of Munster.

Winant, one of the survivors, spent the rest of the war at the infamous Stalag Luft III, a Prisoner of War (POW) camp for aircrews at Sagan in western Poland. (The 390th Bomb Group Memorial Museum Foundation, Marshall B. Shore, “Target Munster,” 10 October 1943)

Another rocket caught a B-17 amidships. Splintered in half, the crippled B-17 collided with another Fortress below. The figure of a man blew out of the flaming mess of bombers, and hurtled down towards Germany, four miles below. He did not have a parachute. (Wright, 268). Part of this scene is depicted in Masters, with the destroyed aircraft ascribed as being with the 100th Group. The show identifies one of the destroyed bombers as “She’s Gonna” (serial no. 42-234423), with Crosby’s best friend, Lt. “Bubbles” Payne, on board.

Payne, the series claimed, was killed in action (KIA) as a consequence. In reality, no such bomber existed. Payne was actually KIA on another mission in April 1944.

Also, the destroyed bombers were actually Miss Fortune, under Lt. Wade Sneed and Miss Behavin, piloted by Lt. George Starnes, both of the 390th Bomb Group. Fifteen crewmen died. The destroyer was likely Major Karl Boehm-Tettelbach, the commander of ZG26. (Hawkins, pgs. 192-193)

The Germans concentrated on the 100th Bomb Group occupying the low flight, and in quick succession ravaged the unit until 12 of its 13 Fortresses were destroyed. The last, a B-17 named “Royal Flush”, flown by Lt. Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal of New York, headed towards Munster nearly alone.

The American actor Nate Mann, plays Rosenthal in the series, in what is a captivating portrayal. The virtually unknown Mann (although that may not be true anymore) is easily the best actor in the series.

The real-life Rosenthal was 25 years old when the Munster attack was mounted. He was a bit older and more mature than the other pilots; more restrained when others preferred to race bicycles indoors, more thoughtful when others were flippant, and more sure of his role in the war when the others saw it as an adventure.

“We have the opportunity and ability to stand up for the things in which we believe; we can help those people – captive in Germany and in occupied countries – who can’t speak and act for themselves,” Rosenthal told a fellow officer in real-life. “A human being must look out for other human beings or else there’s no civilization. We are morally obligated to fight.” (Edward Jablonski, Flying Fortress: The Illustrated History, pg. 198)

In many ways, Rosenthal is akin to Eugene Sledge and Robert Leckie, the erudite, sensitive USMC protagonists of The Pacific. The producers of Masters clearly recognized Rosenthal’s value as the humanistic core of the series, but he remains underused until the last episodes of the series.

Back in October 1943, Munster came into view. Rosenthal handed control of the aircraft to the bombardier using the Automatic Flight Control Equipment (AFCE). After the bombs were dropped, Royal Flush made a sharp left turn, back towards home.

As the aircraft turned westwards from Munster, the crew found the skies horrifyingly empty. This too is depicted in the Masters episode, even if the sequence of events is condensed. What Rosenthal and his crew did not know at the time was that the Germans had disposed of the 100th Group in seven minutes as well having blasted eight B-17s from the 390th Bomb Group and five from the 95th Group out of the sky.

“After the [bomb] drop, the fighters began queueing up [on us]; they seemed to be coming in hordes,” Rosenthal said. “I had the [B-17] all over the sky: chandelles, lazy Esses, every manner of violent evasive action.” (Jablonski, pg. 200)

All this is stunningly depicted in Masters, which indicates that Rosenthal and his crew survived the carnage because they threw “Royal Flush” about the sky like a fighter, allowing the B-17’s gunners to shoot down several German pursuers.

“The fighters eventually became discouraged and left and, losing altitude, I headed home,” the real-life Rosenthal said. (Jablonski, pg. 200)

But one of Royal Flush’s engines had been knocked-out and another seriously damaged. (Hawkins, pgs. 146, 152). Nevertheless, Rosenthal and crew reached the Zuider Zee in the Netherlands. Two crew members had been wounded, but the gunners onboard claimed three Luftwaffe fighters shot down. In actuality, the tail gunner, Staff Sergeant Bill deBlasio (not to be confused with the future mayor of New York City), may have single-handedly shot down six attacking German fighters, although he never submitted claims for these. (100th Bomb Group, Record for William de Blasio)

Down to two working engines, the crew jettisoned unneeded objects to save weight. By the time the bomber began crossing the English Channel, the aircraft was down to just a few hundred feet. As the co-pilot, Lt. Winfred Lewis, later related, only “sheer luck, Lt. Rosenthal’s perseverance, good navigation by Lt. Ronald Bailey [of 83 Vermont Avenue, Hempstead, Long Island*], and various prayers in all faiths, the English coast…came into view…at 1639 hours”.

*I lived near Vermont Ave as a kid, and this discovery of Bailey’s antecedent address is amusing.

Rosenthal and Lewis landed the aircraft at the 100th’s base at Thorpe Abbotts on two engines. Later, the ground crews found an unexploded 20 mm shell in a fuel tank. (Hawkins, pgs. 184, 221, 228-229)

The Munster raid cost the 100th Group 12 bombers and 121 men. This destruction fed rumors that the 100th was cursed. However, the 100th’s losses can be explained by the fact that the group often drew the dreaded “Tail End Charlie” position and were frequently at the outer fringes of the combat box, where they were vulnerable to attack.

In Masters, after their return to base, Rosenthal’s radio operator, Tech Sergeant Michael Boccuzzi (played by Riley Neldham), shouts that the powers that be cannot send him up again on another mission. In fact, it is unsure if Boccuzzi actually said this but one of the crew certainly did: “I’m through flying in these things. That’s enough!” (See Jablonski, pg. 200-201)

In Masters, the outburst elicits no response from the rest of the crew.

When a superior officer asks if there were survivors from the fictional B-17, She’s Gonna, Boccuzzi angrily responds that the plane “blew up”. That the others on his crew are not as enraged by the loss of 121 of their group mates reveals how hesitant the script is to tackle emotion, much less PTSD.

Comparing all this with the emotional wallop of the 1949 Gregory Peck starrer Twelve O’Clock High, about a Brigadier-General who takes command of a hard-luck bomb group and renders them honorable at massive personal cost, shows how tempered the Masters script is.

Even when Rosenthal, sent to a rest camp for rest and relaxation, opens up about his experiences and combat, the dialogue is disingenuous, forcing him to ramble, using Gene Krupa (a 1940s band leader) as a metaphor for his interrupted flying streak. Uncompelling stuff.

Compounding the problem are subplots that lead nowhere, such as a relationship between Crosby and an English female officer who is later sent behind enemy lines to Nazi-Occupied Paris, seemingly as part of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The SOE, a British agency, ran British-Allied intelligence agents throughout Nazi-occupied Europe during the war – including at least 42 women. Sixteen died in Nazi hands. Hollywood and British cinema have barely scratched the surface of their heroic deeds.

According to Crosby, the female officer existed (again the problem of following the source material too closely). Her name was Alexandra M “Landra” Wingate, Crosby wrote. In the series, she becomes “Sandra” Westgate – Why? Who knows? A modicum of creative liberty is acceptable, but Crosby neither mentions hair nor hide of the SOE in his book. No Alexandra M Wingate appears in M R D Foot’s seminal SOE in Europe.

In any case, Wingate/Westgate exits the scene without much ado in the latter half of the series.

a clear analyse about a series that in all honesty didn’t appeal to me.

This was a great read and a good analyse of a series with little ambition,

INTERESTING TO WATCH BUT STILL FAR BELOW BAND OF BROTHERS AND THE PACIFIC REGARDING SUSPENSE ACTION AND EMOTIONAL MIMIC SHOWN BY THE ACTORS !!!!!!

Indeed, the characterizations were unfortunately weak.

Pingback: Aces over Berlin – Achilles the Heel