Not soon after the United States entered World War II and became a core member of the western Alliance, Washington began to consider ways to invade Nazi-occupied Europe, “Fortress Europa.” The pressure was especially high on the Franklin D Roosevelt administration to launch the invasion before the end of 1942.

But two years would pass before an invasion could be launched, with the delay in time being directly commensurate with the scale of the challenge.

Initially, the US military had few troops available to invade the continent. Only in mid-1942 was US Army Chief of Staff, General George C Marshal, able to initiate a buildup of US forces in Britain for the return to Europe. The buildup, codenamed Operation “Bolero” had the twin objective of allowing Marshal to assemble troops in England to justify Washington’s “Germany First” policy while simultaneously silencing the US Navy, which sought greater resources, troops and equipment for the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO).

However, the British, especially Prime Minister Winston Churchill, were apprehensive about a cross-channel invasion in 1942 or even 1943 – a prospect made all the more uneasy by the disastrous Dieppe raid of August 1942.

The Dieppe action was an amphibious operation by commandos that was to be a testbed case for a cross-channel assault and prove to the Russians and Josef Stalin that the western alliance was serious about eventually launching a second front in Europe. (Carlo d’Este, Decision in Normandy, Chapter 2, Section 13, Para 29). Unfortunately, the landing in northwestern France, led to most of the Allied landing forces being killed or captured.

That failure strained the Anglo-American alliance as the Americans were then forced to contribute troops and resources to what they considered as “sideshow operations” in the Mediterranean Theater that were so dear to Churchill’s heart. American involvement in the Mediterranean was also driven by the US army’s comparative combat inexperience in 1942 (when compared to Great Britain), which meant that the United States had to follow England’s lead, and so the US found itself engaged in various landings and campaigns — in Algeria, in Tunisia, in Sicily and finally in mainland Italy.

US resentment was growing, fueled by suspicion that Americans were fighting and dying in campaigns for the benefit of Britain which planned to re-establish its Mediterranean empire after the war. From the British perspective, the Mediterranean campaign was to remind the world that England was not yet out of the war and capable of hitting back at the Third Reich.

Marshall and the United States also could not go their own way. In addition to their inexperience, they were dependent on Britain for its industrial and military support. In 1942-1943, the United States was not yet the industrial powerhouse it was destined to become and the country was reliant on Britain’s factories which churning out ammunition, troop housing, aircraft, plus key landing craft which were required for the invasion.

In addition, nearly all units of the Royal Navy (RN) and the Royal Air Force (RAF) were locked in combat with the Germans, which America at this stage, could only hope to augment.

However, during the Casablanca conference in January 1943, the question of a cross-channel invasion of France was settled. Senior government and military official had decided that the amphibious beach assault would take place sometime after 1 May 1944 and would be codenamed “Neptune.”

Neptune itself fell under Operation “Overlord”, the combined air, sea and land offensive to invade Normandy and western Europe.

D-Day Planning

Two months after the conference, British Lt-General Frederick Morgan was appointed to the role of Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), with with US Brigadier General (soon Major General) R W Barker as his deputy. However, no one had yet been appointed to the position of Supreme Allied Commander.

On the shoulders of Morgan and Barker (and their staff) lay the daunting task of drafting the preliminary plans for the invasion. (History of Cossac, The Historical Sub-Section, Office of Secretary, General Staff, Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force, May 1944 https://history.army.mil/documents/cossac/Cossac.htm)

At their London headquarters in Norfolk House, St James Square, Morgan and his people began to tackle some of the more key problems of a cross-channel invasion.

First, they had to select the landing area. Then they had solve the daunting problems of transport, supply and support.

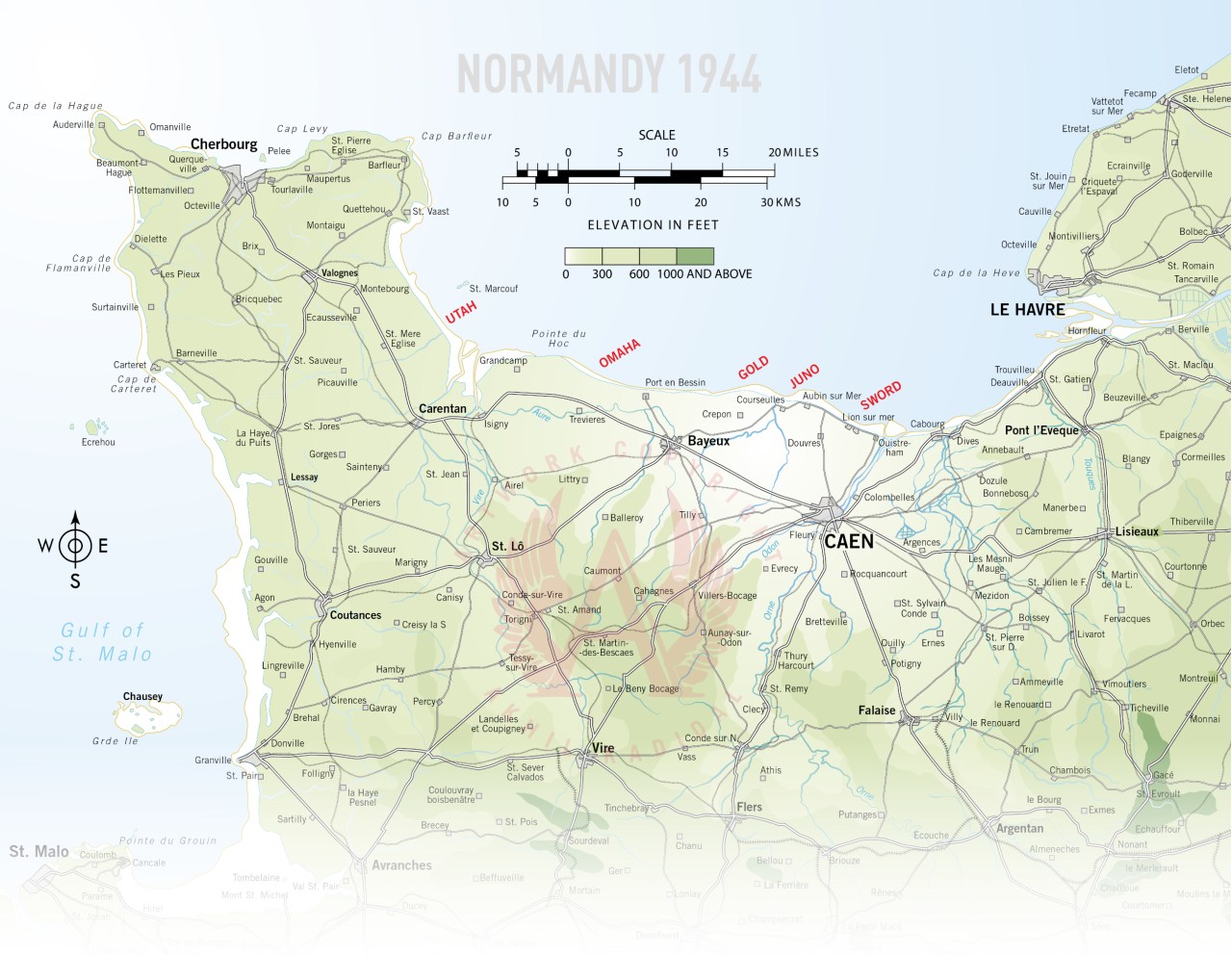

Normandy was chosen because it was well within fighter range and it was less well defended than the much closer Pas de Calais area – the first choice. In addition, if the port city of Cherbourg in the Cotentin peninsula, could be captured early, then the issue of supply could be considerably resolved.

By when the plans were completed by the end of 1943, US General Dwight D Eisenhower was chosen as Supreme Commander. Almost immediately, in January 1944, the planning staff ran into a problem in the form of British General Bernard Montgomery, victor of the North African campaign.

After having returned to England by ship on January 2, fresh off his conquests in the Mediterranean, “Monty” did not have a high opinion of “Ike” as the American supreme commander was known. “Nice chap,” he said. “No general.” (Alistair Horne, The Lonely Leader: Monty 1944-45, pg. 100)

“Ike? Nice chap. No General.”

- Bernard Montgomery

Next, Montgomery stirred up trouble by insisting that Morgan’s plan was flawed. It was not an unfair estimation.

Morgan’s initial plan (drafted in the summer of 1943) called for an invasion force of three divisions to land on three beaches and use the combined firepower of their units to force a breakthrough. An airborne force was to also be dropped on Caen to secure the city. (d’Este, Decision in Normandy, Chapter 3, Section 14, Para 17).

COSSAC thought that an amphibious landing zone ahead of the Sommervieu-Bazenville ridge would allow Allied troop to branch out towards the important Norman cities of Caen and Bayeux. The planners, acting on Allied estimations made on 1 September – which stated that “generally speaking devoid of natural anti-tank localities” would allow Allied armored formation to make rapid strides inland. (Study of Tasks of ‘Overlord’ Assault Divisions, 1 September 1943, LAC RG 24, vol. 10540, file 214A21.014 (D6) & Marc Milner, Stopping the Panzers: The Untold Story of D-Day, Ch 1, 13%)

But Montgomery saw the narrow point of operation as a liability rather than strength. Within three days of his arrival, he was promoting his own of strategy of landing six divisions on five beaches stretching from the seaside town of Ouisterham in the east, to the base of the Cotentin Peninsula in the west, an area that would eventually become “Utah” beach.

Montgomery also wanted a force of three airborne divisions landing at night behind the coast, to protect the flanks, to capture important installations and to sow confusion within the enemy. Finally, Montgomery replaced the entire staff of the British 21st Army Group with his own staff from the British 8th Army, which he had led to victory in North Africa.

Montgomery’s tweaks were sensible. Allied High Command formally accepted Montgomery’s updated plan on 23 January 1944 and by April, the strategy was being polished. The Americans were to land on the western flank, while the British-Canadians landed on the east.

This was logical, for if the Americans captured Cherbourg, Brest and the Loire ports, then replacements and supplies could be shipped directly to the port from the United States without the delays inherent in an England stopover.

Left to right, front row: Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder Deputy Supreme Commander, Expeditionary Force; General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, Expeditionary Force; and General Sir Bernard Montgomery, Commander of the British 21st Army Group.

Back row: Lt-General Omar Bradley, commander US 1st Army; Admiral Sir Bertram H Ramsay, Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief (Expeditionary Force); Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Allied Air Commander in Chief (Allied Expeditionary Air Force), and Lt-General Walter Bedell Smith, Chief of Staff to Eisenhower.

Assembling the Troops

Meantime, forces in England were activated for operations. Two mobile brigade combat groups were placed on standby in Kent and Sussex to deal with German commandos who could potentially land to disrupt the build-up. Not that the Germans could make such an attempt. By now, Britain was an island bulging at the seams with men and equipment crammed into every available base and field.

Since 1942, Marshal had dispatched thousands of US troops to Britain, as well as vast amounts of supplies. The island groaned under the weight of 2,000 camps and airfields populated by 950,000 US troops and 600,000 British, commonwealth and Free Force servicemen organized into 20 US and 16 British, Canadian, and Polish divisions. On top of the thousands of American GIs already in Britain, another 37 US divisions were to slated to arrive in Europe, either to decamp in Britain or land directly in Europe after the invasion.

Whole sweeps of the horizon in the southern England were covered with row upon row of tanks, artillery guns, armored cars, aircraft and tents or Nissen huts housing battalions of men. People driving in the southern counties came upon an airfield every five miles, housing entire groups of bombers or fighters. Farmers’ fields were home to a strange harvest – field guns and howitzers, while half-cylindrical steel containers sheltering piles of ammunition lined the grassy shoulders of the country roads.

A joke went around that only the thousands of barrage balloons floating up in Britain’s skies kept it from sinking beneath the waves. (Michael Wright (ed), The World at Arms, Readers Digest, 1989; pg. 296)

Every formation needed camps in Britain, trains to move them, areas for training and supplies. Each armored division required the equivalent of 40 ships to reach France, almost 386,000 ship tons compared to 270,000 tons for an infantry division.

The initial American landing force would comprise of 130,000 men, with another 1,200,000 men following behind by D+90. With them would also go 137,000 jeeps, trucks and half-tracks, 4,217 tanks and full-tracked vehicles and 3,500 artillery pieces. Some five million tons of supplies were needed to feed and supply these troops. (See: Normandy, US Army Center for Military History, pg. 14, https://www.history.army.mil/brochures/normandy/nor-pam.htm)

Wildcard Hedgerows

Yet, despite their careful attention to detail, Allied planners overlooked one crucial factor: the challenges posed by the French bocage on military operations. That the fighting in Normandy would largely devolve into close-combat style battles dictated by the hedgerow, was improperly investigated, and would create formidable problems later.

US Army engineers of the Office of the Chief of Engineer (OCE) Intelligence Division who had been given the task of preparing 1:25,000 scale battle maps covering 16,000 square miles of northern France, even omitted fine details in their maps such as hedgerows to meet their deadlines for D-Day. In recompense, they included a photomap of the area with each map. (Alfred M Beck, Abe Bortz et al, Corps of engineers: The War Against Germany, US Army Center for Military History, 1985; pg. 296)

More egregiously, allied troops were untrained for the the kind of close-range fighting they would find in Normandy. One example was the British 7th Armored Division, the famed “Desert Rats” who had earned their name in the North African campaign. This division was still training in the flatlands of East Anglia.

Neither the fact that the Germans were masters in defense nor that they had the capacity for fierce resistance, especially in the closed-knit areas of the bocage, was properly considered.

As a senior staff officer later said: “We simply did not expect to remain in the bocage long enough to justify studying it as a major tactical problem.” (Max Hastings, Overlord, Pan, 2010; Chapter 2, Section 1, Para 132)

The Accepted Plan

The final invasion plan called for four Allied corps to land troops on five beaches.

On the far left at “Utah” beach, US VII Corps would send in the US 4th Infantry division. At “Omaha,” US V Corps would be led ashore by the American 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions. At “Gold,” British XXX Corps would send in the 50th British Division.

At “Juno,” British I Corps would be led in by the 3rd Canadian Division, and at “Sword,” by the 3rd British Infantry Division.

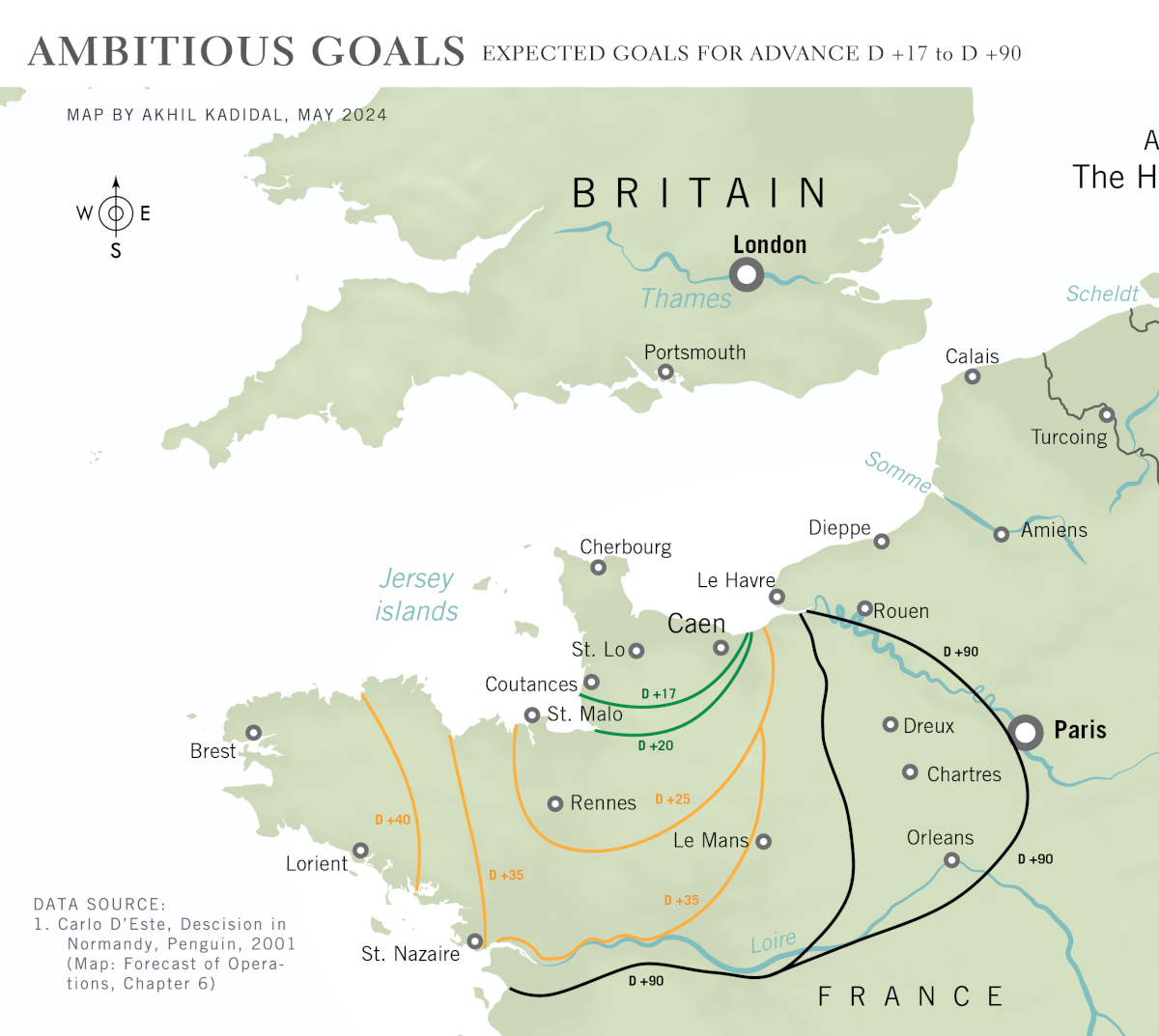

Following the landings, the US 1st Army, comprising the V and VII Corps, had to drive up and capture Cherbourg with minimal delay.

The emphasis was to secure the area north of the Douve River and east of the Merderet River to protect the landing zone.

The US 82nd Airborne Division was to secure the western edge of the peninsular invasion zone, particularly the town of St. Mere-Eglise, while the 101st Airborne Division was to secure the beachhead by seizing four roads leading from the beach across the inundated area.

The US 4th Infantry Division would establish the beachhead at “Utah” and drive on Cherbourg with the US 90th Infantry Division, which was scheduled to land on D+1. However, the 90th’s 359th Regimental Combat Team was attached to the 4th Infantry for D-Day operations.

Meanwhile, the British Second Army, comprising I and XXX Corps, would take Caen to tie down and batter German forces coming from Northern France and the Low Countries. Later, reinforcements, primarily in the form of the US Third Army commanded by the firebrand US Lt-General George S Patton would arrive from England and drive south, clearing Brittany, seizing Nantes and St Nazaire, to cover the southern flank.

“Overlord” was meant to be a masterfully orchestrated assault. But from the outset there were problems, including strident debates and anger about how to best use air power.

Mast image: A contemporary painting by Barnett Freedman. shows the interior of the busy Headquarters Room in Southwick Park, Portsmouth during preparations for the D- Day landings. The wall map encompasses southern England, the English Channel and northern France, with various annotations being added. IWM ART LD 4638