The Air Plan

Air power before “Overlord” was a particularly thorny problem – Not that there was any shortage of men and machines. The Allies had access to seemingly endless echelons of combat squadrons equipped with heavy bombers to light bombers, fighters to fighter-bombers, reconnaissance machines to transports.

Usage was the problem.

For one, wrangling the heavy bombers of the Royal Air Force’s (RAF) Bomber Command had been a prickly proposition as its commander, Air Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris, was intractable. Harris believed that air power alone and the pummeling of cities could bring the Germans to heel. He was therefore loathe to reallocate his command to support ground forces participating in the invasion.

The American 8th Air Force, which was also flying out of Britain under the command of US Lt-General Carl Spaatz, was a different animal but no less slaved to its raison d’etre of attaining air superiority over all other considerations.

A plan was needed to coalesce Allied air power into combined operations by the army and navy against the Germans in Normandy. In February 1944, Montgomery along with Admiral Bertram Ramsay, commander of the Allied expeditionary naval forces, and Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, came up with a joint plan detailing the role of the three services (air, ground, sea) before and during the invasion.

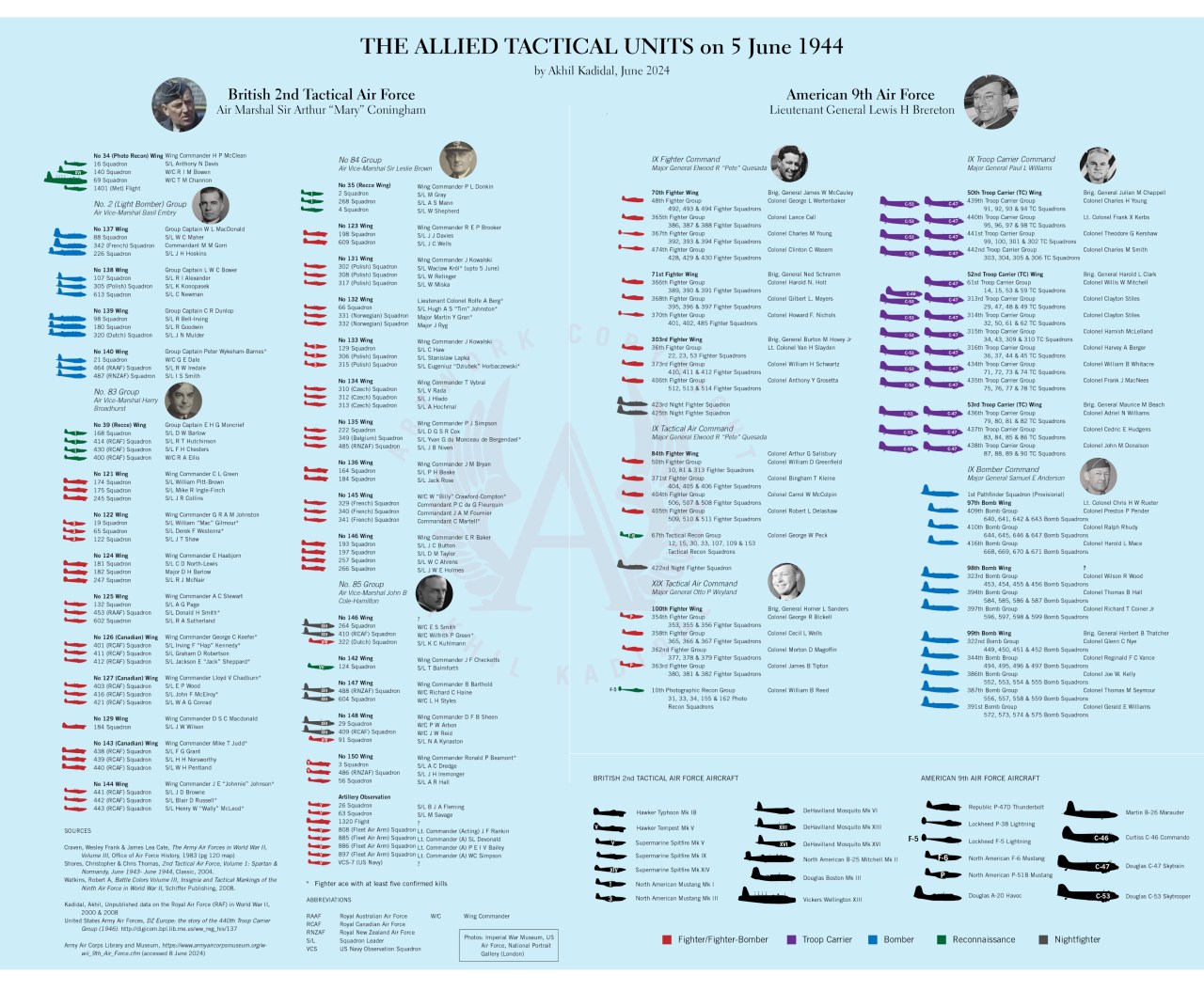

The air component of “Overlord” called for the air forces to knock out the German Luftwaffe (air force) and destroy communication links in France. The Allies had four air forces for this task: Harris’ Bomber Command, the British 2nd Tactical Air Force (2nd TAF), the US 8th Air Force and the US 9th Air Force.

The “Preparatory Phase,” which began from D-90, intensified attacks on vital infrastructure, coastal batteries, command centers, and German air power, including bombing aircraft and aircraft engine factories. (The Effectiveness of Third Phase Tactical Air Operations in the European Theatre, 5 May 1944 to 8 May 1945, Army Air Forces Evaluation Board in the European Theater of Operations, August 1945; pg 45)

Two Phases

Itself divided into two stages, the Preparatory Phase’s first stage called for “concentrated attacks against servicing, repair, maintenance, and other installations, with the intention of reducing the fighting potential of the enemy air forces.”

The second stage was designed to “render unserviceable” all airfields within 210 km (130 miles) of the assault beaches, the purpose being to drive the Luftwaffe back to a distance where it would have lost the advantage of being based near the planned frontline.

The second phase called for isolating the battlefield by interdicting road and rail networks. Once the invasion began, Allied air forces would concentrate on battlefield interdiction and close air support. However, to keep the “Overlord” landing areas secret, deceptions had been planned to encourage the Germans to devote their attention to the Pas de Calais area.

Allied strike planners therefore had to schedule vastly more operations across the range of likely landing sites rather than just at the true sites in Normandy. For example, rocket-armed Typhoon fighter-bombers of the 2nd Tactical Air Force attacked two radar installations outside the planned assault area for every one they attacked within.

In the five months before D-Day, only 38% of 8th Air Force bombs were directed against the Luftwaffe as a result of invasion preparedness. On 14 April 1944 control of all Allied air forces passed to the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), and up to D-Day, selection of all targets was made by SHAEF.

Allied heavy bombers began cratering France and Germany, while the RAF’s fighter-bombers and American B-26 Marauders attacked smaller but important targets: V-1 Flying Bomb launch sites and radar bases in France, Belgium and Holland.

A Free French pilot, Flight Lt Pierre Closterman, recalled one such attack site in April 1944: “Like a fan spread out, all the Spitfires turned on their backs one after the other and dived straight down. This time the flak came up straight away. Clusters of tracers began to come up towards us…Shells burst to the left and right, and just above our heads a ring of fine white puffs from the 20 mm cannons began to form, scarcely visible against streaky cirrus clouds. I had only just begun to get the target in my sights when the first bombs were already exploding on the ground – a quick flash followed by clouds of dust and fragments.” (Pierre Closterman, The Big Show, Paris: Flammarion, 2008, pg. 102)

Beginning in April and continuing with increased vigor in May, allied fighter-bombers went after the Luftwaffe’s airfields and bases in Western Europe, with the aim of neutralizing all airbases within 210 kilometers (130 miles) of the invasion beaches.

From early May 1944, long-range US P-51 Mustangs and P-38 Lightnings were given the task of smashing the French rail network east of Paris, while the region over the landing areas became the hunting ground for squadrons of American P-47 Thunderbolts.

In May, 36 major airfields from Brittany to Holland were hit once or repeatedly, but these were not the only targets open to attack. Locomotives, motorized transports, and even bridges were not safe. (Omaha Beach, US Army Historical Division, Washington, 1994; pg. 3)

Marshalling yards became sponges for medium bomber raids, and between 1 March and D-Day, 36 such assembly yards in Belgium and northern France were hit in 139 attacks. (Ninth Air Force, April to November 1944, AAF Historical Studies No 36; pg. 36) The important yard at Creil, near Paris was hit so severely on May 24, that nearly 60 percent of it lay in shambles. Then in a series of raids in May bizarrely named (but perhaps aptly) “Operation Chattanooga Choo-Choo,” American P-47 Thunderbolts attacked trains, rolling stock, and rail bridges. Rail bridges on the Seine and the Meuse rivers were given first priority.

By 4 June, 10 rail bridges between Rouen and Conflans were knocked out, as were all but one of the 14 road bridges. (Omaha, ibid.)

Rolling stocks were subject to punishing treatment. On 21 May, the most active day for this type of work, some 500 aircraft claimed 46 locomotives as destroyed and another 32 damaged. In addition, a further 30 trains were claimed as damaged. By the end of the month, more than 500 locomotives had been damaged and thousands of passenger cars, boxcars and flat cars lay by the rails, blown to pieces. Rail traffic in France dropped to 35 percent of its March capacity.

The foundation for these types of operations had been built back in November 1943, when the Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF) was formed and took charge of all air forces designated to support the Allied ground invasion.

The stocky Leigh-Mallory was given command of the formation and effectively held overall control of the 2nd TAF and the US 9th Air Forces as well as elements of the US 8th Air Force. Other subordinate units, such as the RAF’s No 38 Group handled the transport of airborne forces, while No 34 (Reconnaissance) Wing, along with Spitfires and Mustangs, flew over the landing areas and the French interior, photographing German defenses.

Meantime, RAF light bombers of No 2 Group were employed in medium-level pattern bombing against radar sites, airfields and rail yards, whereas Mosquitoes concentrated on highly defended vital targets. The US 9th Air Force, alone flew 264,938 sorties from October 1943 to May 1945, excluding medium bomber operations.

The Germans, secure in their bunkers, never expected such a coordinated attack and had no answer for it. There were just too many rail tracks to watch, too many bridges to patrol and too many important locations to defend.

The Allies flew more than 200,000 sorties in the preparatory period, dropping about 200,000 tons of bombs dropped on targets in France and Germany. But the cost was high, and about 2,000 Allied aircraft were shot down with the loss of more than 12,000 fliers, excluding an equal number of French and Belgian civilians – victims of the bombing. (D’Este, Ch. 15, Section 27, Para 21)

That the attacks were effective is beyond doubt. One German report testified on June 3: “Paris has been systematically cut off from long distance traffic, and the most important bridges over the Seine have been destroyed one after the other. It is only by exerting the greatest effort that military traffic… can be kept moving.” (Williamson Murray, Strategy for Defeat, Air University Press, 1983; pg. 271)

Also, by June, the Luftwaffe on the western front (including for homeland defense) had thought to have been reduced to 745 single-seat fighters and only 21 tactical aircraft by D-Day. (Effectiveness of Third Phase Tactical Air Operations in the European Theater; pg. 42) In contrast, the combined strength of the Allied air forces in England was 6,340 aircraft, out of which 2,230 were fighters. (Notes on the Operations of 21 Army Group, 6 June 1944 to 5 May 1945; pg. 4)

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing at Allied high command. Eisenhower and and his deputy, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, discovered that the American public and government were irate that all three important subordinate commands had gone to Englishmen: Sir Bernard Montgomery for land, Sir Bertram Ramsay for sea, and Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory for air.

Within the air realm there was also a clash of personalities that threatened to derail the war effort. Air Marshal Sir Arthur “Maori” Coningham, the commander of the British 2nd TAF was at odds with Montgomery whom he though had stolen all the glory of the victory in North Africa.

In the desert the two men had worked in close harmony, living side by side in caravans and closely coordinating air-ground actions. When Montgomery gained fame and massive publicity for his victory over Rommel, the ambitious Coningham felt slighted and from that time forth relations deteriorated to the point where Montgomery in Normandy would deliberately bypass Coningham; this only intensified their bad relations as the frustrated air marshal constantly criticized Montgomery’s actions.

(D’Este, Ch 7, Section 25, Para 20)

Montgomery compensated bypassing Conningham and dealing directly with Leigh-Mallory on strategic bombing and with Air Vice-Marshal Harry Broadhurst, commander of No 83 Group within the 2nd TAF on tactical matters.

To complicate matters, the Tedder, the deputy commander of SHAEF, also disliked Coningham but respected him. Tedder also disliked Leigh-Mallory and but did not respect him, thinking him unsuited for the role of commander of the AEAF (Arthur Tedder, With Prejudice, pg. 564)

Problematic Mallory

The stout and aggressive Leigh-Mallory was problematic on his own. He had come into the limelight during the Battle of Britain in 1940, while commanding the RAF’s No 12 Group which was in-charge of protecting the area north of London and the midlands.

He advocated controversial massed fighter attacks on German bombers (“Big Wing”), and repeatedly committed large unwieldy air units against the Germans while not achieving favorable results for the effort expended. His reputation was subsequently damaged following his politicized appointments to commands formerly held by Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park and Air Marshal Dowding, two upright officers who were the true victors of the Battle of Britain.

One RAF fighter ace, Alan Deere, later said that Park and Dowding had “won the Battle of Britain but lost the battle of words that followed, with the result that they … were cast aside in their finest hour.” (Patrick Bishop, Fighter Boys, Penguin, 2003; Chapter 18, Para 1)

Now in 1944, Leigh-Mallory was not only unpopular among the British but also among the Americans, who saw him as gloomy, hesitant and conservative.

In late 1943, Brigadier-General James “Jumping Jim” Gavin of the 82nd US Airborne Division, who had returned from airborne operations in Sicily to help plan “Overlord,” was asked by Leigh-Mallory to describe airborne operations.

“Now I want you chaps to tell me how do this airborne business,” Leigh-Mallory had said. But after listening to Gavin and his staff for a while, he then remarked flatly: “I don’t think anybody can do that.”

Gavin exploded: “What do you mean nobody can do that? We just got through doing it in Sicily!” (Hastings, Ch. 2, Section 1, Para 155)

Skepticism

The US 8th Air Force was engaged in a series of prolonged battles with the German Jagdwaffe (Fighter force) over the Reich from March 1944. With the RAF flying fighter sweeps over Normandy and south of the Seine river, and with American P-51 Mustangs prowling over eastern France and Germany, the Luftwaffe began to lose the war of attrition.

However, the claims of destruction meted out to the German Luftwaffe proved so fantastic that many in Allied circles proved unwilling to accept them. This skepticism prompted the broaching of elaborate plans to cover the landings, in anticipation of a huge battle for air supremacy over the beachheads.

One SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) estimate assumed that between 300 and 400 German fighter aircraft would contest the landings.