It is on the beaches that the fate of the invasion

will be decided and, what is

more, in the first 24 hours.

– Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Adolf Hitler could see the future in 1943. “If they attack in the west that will decide the war,” he said. (Max Hastings, Overlord, Ch 2, Section 1, Para 190) This was no exaggeration. Over the past three years, the Germany had lost heavily.

The Eastern Front had consumed 1.51 million German lives alone up to the start of 1944 (not counting captured or maimed), according to the German historian Rudiger Overmans (See Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Oldenburg, 2000). The Russians, who had taken greater losses, were still advancing. Between the invasion of Russia on 22 June 1941 and to end of May 1944, the Germans lost 1,860,046 men in the east (Overmans, Table 59: Gesamtverluste an der Ostfront, pg. 277)

Between May 1943 and November 1944, the Wehrmacht alone lost another 145,027 men in Italy (Burkhart Müller-Hillebrand, Das Heer 1933–1945. Entwicklung des organisatorischen Aufbaues, Vol III, Der Zweifrontenkrieg. Das Heer vom Beginn des Feldzuges gegen die Sowjetunion bis zum Kriegsende. Mittler, Frankfurt am Main 1969; pg. 265). The only respite Germany could get was to defeat the cross-Channel when it came.

If the invasion was thwarted in 1944, Hitler believed that the Allies would be forced to wait another year before trying again. This could give Germany the opportunity to concentrate its forces and finish off the Russians. By then, Hitler argued, secret weapons and the Me262 jet fighters would be coming off the production lines in sufficient numbers, enabling his forces to beat back the western allies, when they returned in 1945.

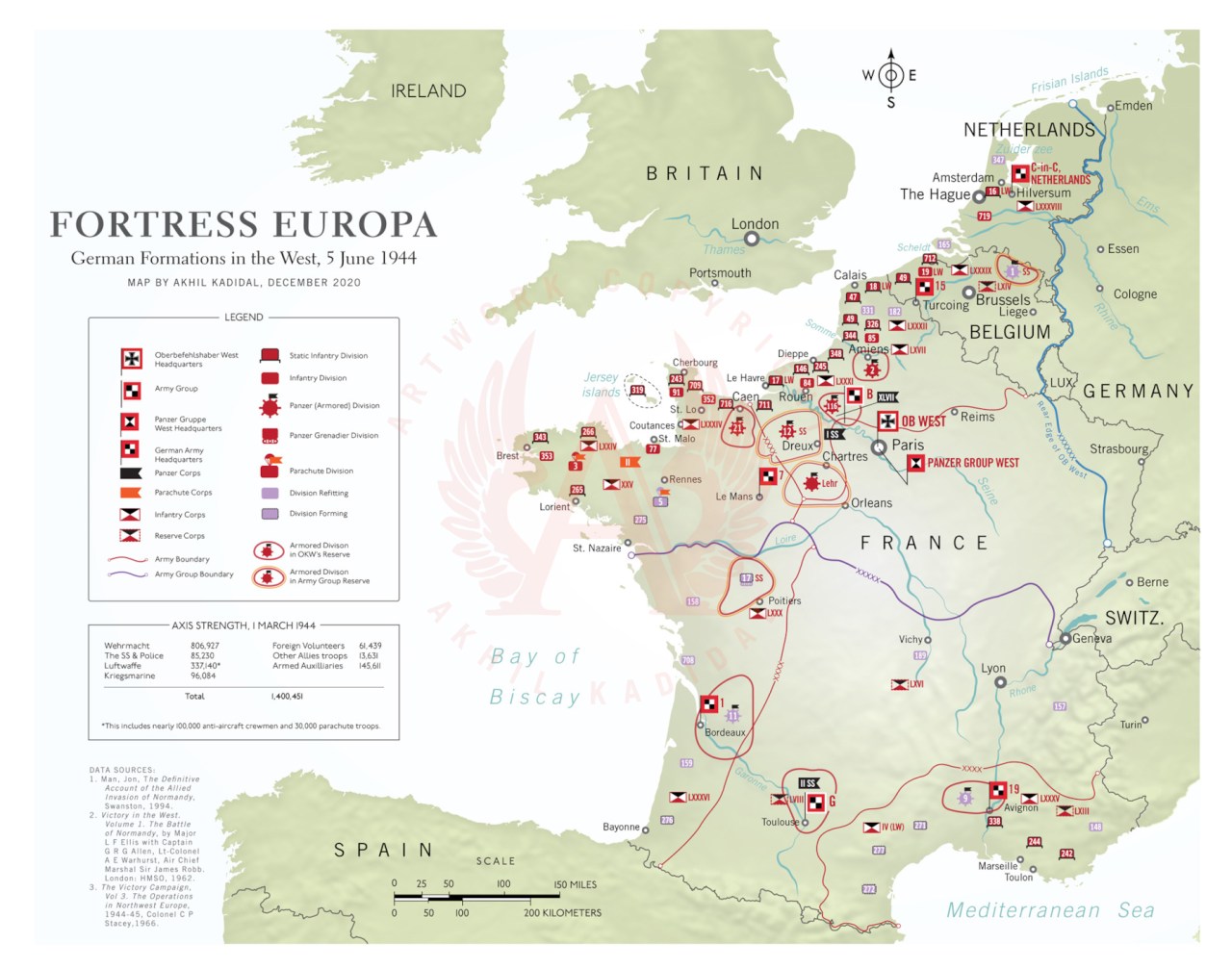

But when General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff at German High Command told Oberbefehlshaber West (OB West or Western Front HQ), toured the western defenses in January 1944, he found that touted Atlantic wall was incomplete. Jodl also discovered that every division in France had been depleted in the constant diversion of manpower to the Russian Front. The Germans had 59 divisions in the France and the Low countries by the time of the invasion (out of which, some 41 were arrayed along the western coastline). Seventeen divisions were in Normandy and Brittany. Only eight of were along the Normandy coast or in position to counter a potential invasion.

Hitlerjugend

Among these was the 12th SS Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) division, which had a manpower strength of nearly 20,500 troops and 66 Panther tanks, which made it one of the strongest divisions in Europe – on any side. Its troops were largely young and idealistic young Nazis whose high morale made them dangerous opponents.

The division was formed primarily volunteers aged between 17 and 19, although boys aged 16 and under also joined. Between July and August 1943, some 10,000 recruits of that age arrived at the training camp in Beverloo, Belgium. (See https://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/hitleryouth/hj-boy-soldiers.htm & Tim Saunders & Richard Hone, 12th Hitlerjugend SS Panzer Division Division in Normandy, Pen & Sword, 2021; Ch. 1, Section 9, Para 2)

As I look at this image, I think: What did these dipshits think they were doing, wearing the uniform of a regime which saw them as racial inferiors?

The Elite and the Poor

Interspersed between the average and elite were approximately 75,000 Russian and Polish “volunteers” press-ganged into German uniform. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of OB West, was unimpressed. “The Russians constitute a menace and a nuisance to operations,” he wrote. (Tim Saunders, Gold Beach – Jig, Leo Cooper, 2002; pg 37)

Another commander, Lt-General Karl von Schlieben of the 709th Infantry Division, remarked: “We are asking rather a lot if we expect Russians to fight in France for Germany against Americans.” (Trigg, Jonathan, D-Day Through German Eyes: How the Wehrmacht Lost France, Ch 6, Section 16, Para 32)

The Germans attempted to excise these unreliable eastern troops from the battle zone in the days before D-Day. General Gunther Blumentritt noted shortly before D-Day that only four of these Ost Truppen battalions remained with LXXXIV Korps and only two of these were committed in the coast front.

“One battalion, which was noted for its trustworthiness, was committed on the left wing of 716th Infantry Division, at the request of this division,” he said. “The other Russian Battalion was committed on the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula.” (Saunders, Gold Beach – Jig, pg. 37)

The first was 441st Ost Battalion which was deployed at Meuavanias in what would become “Gold” sector, with a thousand Russian troops and 270 German officers and NCOs. The other was the 795th Georgian Battalion of von Schlieben’s 709th Division.

North of Caen was the 716th Division, a slovenly and lethargic unit stationed in Normandy since March 1942. It had no combat experience and was weak with only 7,771 men, including men from two other Ost Battalions: 642 and 439. (Niklas Zetterling, Normandy 1944, Casemate, 2019; 716. Infanterie-Division, Part 2, Section 23, Para 341)

However, along a long stretch of beach which reminded the Germans of Salerno in Italy where an Allied invasion force had landed in 1943, Rommel deployed the 352nd Infantry Division, a hardened formation made up of 12,700 first-rate troops (including Russian front veterans). Commanded by Lt-General Hugo Kraiss, the division manned a expansive defensive network comprising anti-tank barriers, bunkers, cannons and heavy weapons from May 1944, some of which was set up on high-bluffs overlooking was to become “Omaha Beach.”

The presence of the division in this area was one of the great intelligence failures of World War II. It was not that the Allies did not know the 352nd was in Normandy, but they thought it was occupying ground near St. Lo, further inland. Instead, its two infantry battalions stretched across the landscape from the Vire to Arromanches, while its heavy weapons, including 14 Marder 38s and 10 Sturmgeschütz III’s of Panzerjäger-Abteilung 352 waited at Birciquiville and Chateau Colombieres about 15 km south of Pointe du Hoc. The divisional artillery, comprising new 105mm and 150mm guns, waited behind the coastline. (Zetterling, Normandy 1944, 352. Infanterie-Division, Part 2, Section 23, Para 73)

The Allies feared that the choice of Normandy was obvious – not without justification. Rommel, for one, suspected that the invasion would materialize in Normandy, as did Hitler, who had a premonition of the landings in this part of France. Consequently, Rommel envisioned two defensive belts along the coastline: three lines of narrow-band obstacles on the beaches covered by defensive units (which Eisenhower termed as a “one of the worst problems of the days”) and strongpoints up to five miles inland. (Gordon A. Harrison, Cross-Channel Attack, US Army Center for Military History; pg. 177, footnote 75).

But the belts were largely incomplete in several sectors, including at “Omaha.”

The Germans, however, had access to reserves. Of 17 divisions based in southern France, most would be on their way to Normandy within a month, including three panzer divisions and one SS panzergrenadier division.

Such calculations made Churchill and Eisenhower apprehensive in the days before the assault began. The bad weather multiplied headaches. D-Day was originally intended to take place on June 5. But on 1 June, the warm and sunny weather of summer broke into a tumult of rain. Visibility was poor and heavy winds began to whip up five-foot swells in the English Channel.

Bad weather

For Eisenhower, the bad weather meant that Allied air power could not be used effectively to support the landings. He deemed the invasion risky if air power was absent. Consequently, a prearranged signal was sent on the morning of 4 June (a Sunday) to the invasion fleet which was already out at sea, asking them to return. The invasion was postponed by 24 hours.

Then at 9.30 pm on Sunday, 4 June, Eisenhower called a meeting with his commanders. There, Royal Air Forces (RAF) Group Captain James Stagg – the head of the RAF meteorological department – offered a glimmer of hope. Reports from weather ships indicated that a brief period of clear would begin from the early hours of June 6. (Harrison, pg 272-273)

But Stagg’s forecast was not all stellar. He cautioned that the rain front over the assault area could clear in two or three hours and the clearing would last until the morning of 6 June, Tuesday. Cloud conditions would allow bombing on Monday night and Tuesday morning but Stagg’s team thought the rest of Tuesday would be beset with considerable cloud cover. Stagg also thought that the cloud base would just be sufficient for the spotting of naval fire.

Eisenhower faced a hard decision. The fates of tens of thousands of men weighed on his mind. A wrong decision would not only consign thousands to their deaths but could even result in the failure of the landings. Of the four major amphibious assaults conducted in the western hemisphere, two of the most recent had been problematic.

The first, the landings in Vichy French Morocco had been within expectations, as were Sicilian landings in 1943. The invasion at Salerno had been less stellar and the worst had been the Anzio operation, where the landing forces had floundered on the beach, in part due to indecisiveness of their commander.

That last failure had prompted Churchill to comment that “I hoped we were hurling a wild cat onto the shore but all we got was a stranded whale.” (Anzio – The Invasion That Almost Failed, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/anzio-the-invasion-that-almost-failed)

The stakes were high. To fail at Normandy could mean, as Hitler believed, an end to Allied dreams of a second front in western Europe in 1944. To Eisenhower’s dismay, his deputy, Tedder, was unenthusiastic about launching the invasion on the night of June 5/6, arguing that effective air support needed good visibility. However, both navy and army chiefs were willing to go through with the invasion.

Eisenhower turned to Montgomery and asked, ” Do you see any reason why we should not go on Tuesday?”’ Montgomery’s reply was immediate: ‘No. I would say – Go.”

At 9.45 pm, Eisenhower announced his decision. ”I’m quite positive we must give the order. … I don’t like it, but there it is …. I don’t see how we can possibly do anything else.” (Harrison, pg. 274)

At a second meeting at 4 am on 5 June, Stagg confirmed that the weather prediction for 6 June remained sound. Eisenhower reaffirmed his decision to invade France. Signals were dispatched to the invasion armada that D-Day was now 6 June. (D’Este, Ch 7, Section 19, Para 13).

There was no turning back now. Eisenhower had a letter drafted in case the invasion failed:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air, and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.

June 5

(D’Este, ibid)

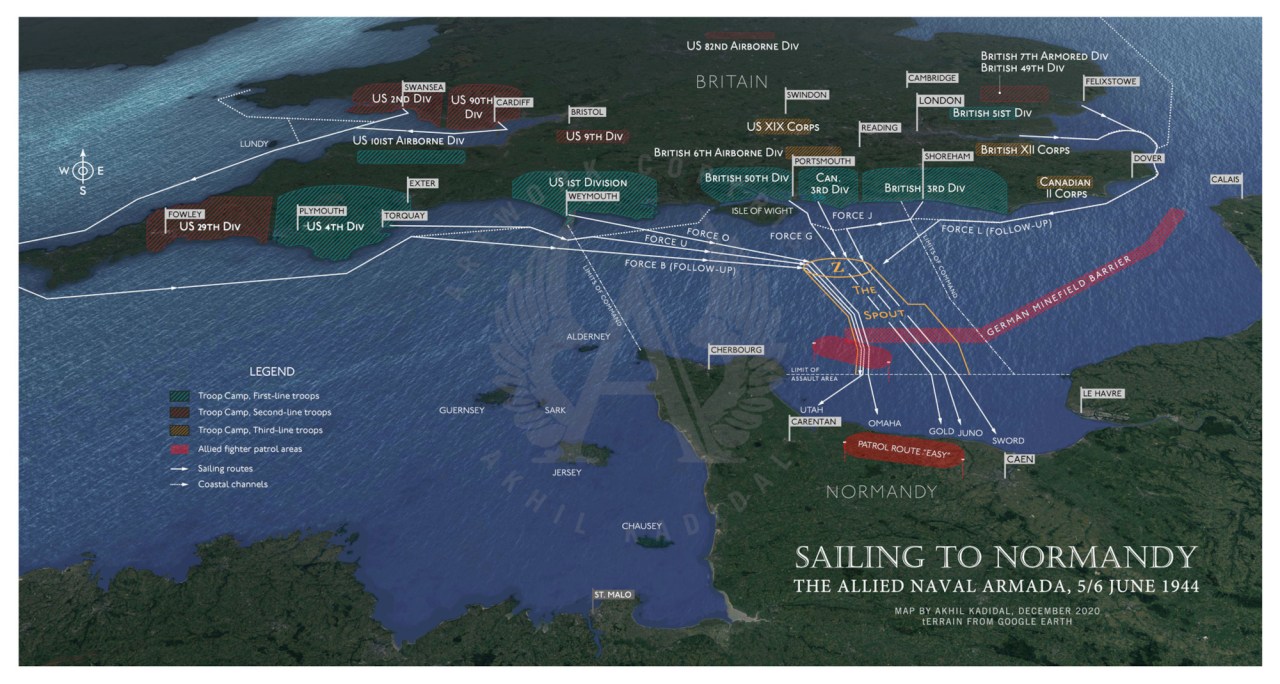

On the evening of 5 June, from ports all along the southern coast of England, the great invasion armada – nearly 7,000 vessels (from battleships to motor torpedo boats, from large troop transports to tank landing ships), started to pull out towards to the Channel and France. Among them were 4,126 landing ships and 1,213 naval combat ships.

As they headed out, Montgomery’s voice could be heard over the radio: “On the eve of this great adventure, I send my best wishes to every soldier in the Allied camp…To us is given the honor of striking a blow for freedom, which will live in history. And in the better days that lie ahead, men will speak with pride of our doing. We have a great and a righteous cause, [and] with stout heart and enthusiasm for the contest let us go forward to victory.” (https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/d-day/files/montgomery-message)

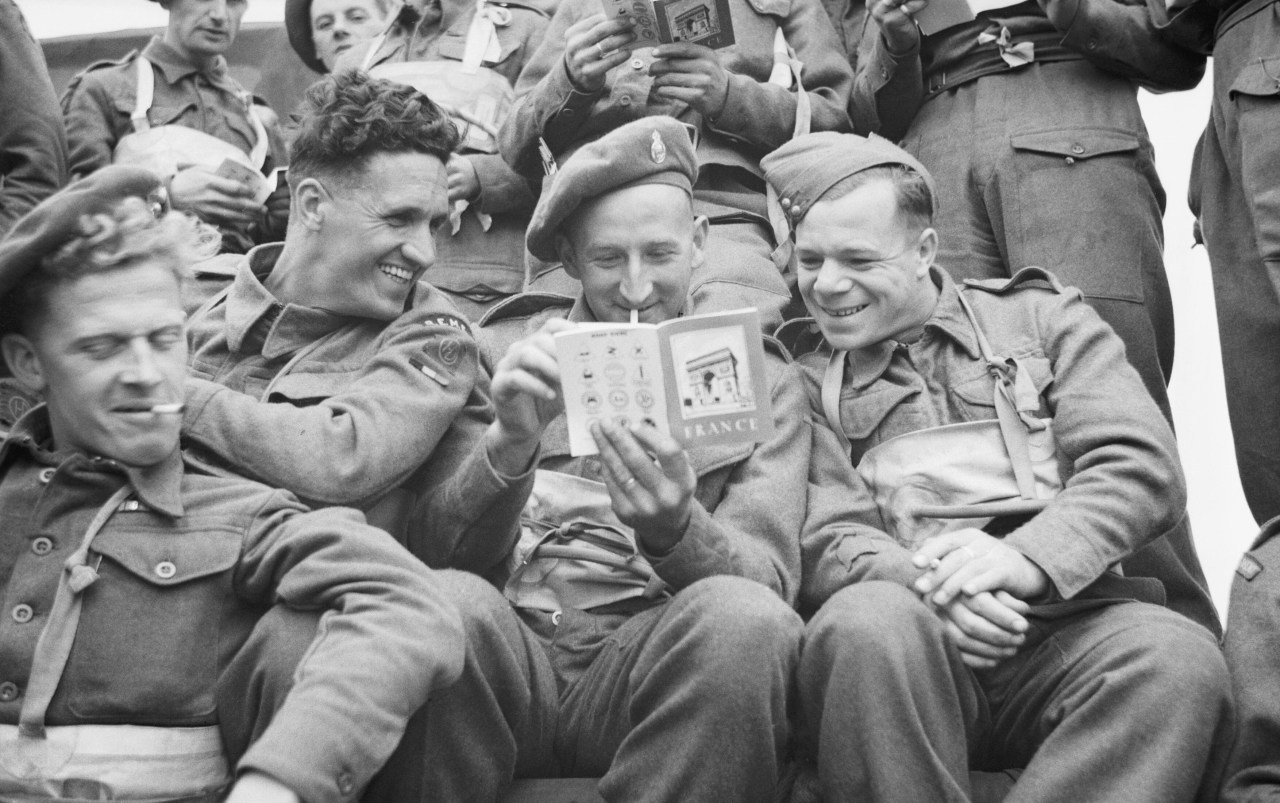

War correspondent Ernie Pyle (pictured in the above New York Times photo, in the center and wearing a US Marine Corps cap), who was accompanying the naval armada, described the scene:

“As we came down, the English Channel was crammed with forces going both ways, and as I write it still is. Minesweepers had swept wide channels for us, all the way from England to France. These were marked with buoys. Each channel was miles wide. We surely saw there before us more ships than any human had ever seen before at one glance…As far as you could see in every direction, the ocean was infested with ships. There must have been every type of oceangoing vessel in the world. There were battleships and all other kinds of warships clear down to patrol boats. There were great fleets of Liberty ships. There were fleets of luxury liners turned into troop transports, and fleets of big landing craft and tank carriers and tankers. And in and out through it all were nondescript ships – converted yachts, riverboats, tugs, and barges.” (Ernie Pyle, Brave Men, Michael O’Mara books, 2016; pg. 381)

As night fell on 5 June, the sea armada was by now across the Channel. It now lay in wait under the cover of darkness, counting off the hours until 6 am – the scheduled time for the naval landings to begin.

In England, British and American paratroopers began to file into their C-47 transports and their gliders. At the 101st Airborne Division’s camp at Greenham Common, Eisenhower appeared. Word later emerged that Eisenhower had been compelled to see the men whom he believed he was sending to their deaths. He had expected massive casualties among the paratroopers, a fear fed by the Leigh-Mallory who on 30 May appeared to be trying to get Eisenhower to cancel the airborne landings.

“Casualties to glider troops would be 90 percent before they ever reached the ground. The killed and wounded among the paratroops would be 75 percent,” Leigh-Mallory said, according to Eisenhower’s book Crusade in Europe. (Eisenhower, Vintage, 2021; pg. 296) These were statistics which haunted Eisenhower.

Speaking to the paratroopers as they stood erect, their faces blackened, their bodies festooned with the kit of war, Eisenhower began asking them questions and wondered if there was anyone there from Kansas, his home state. He finally fixed on one man: Lt. Wallace Strobel of Saginaw, Michigan.

Historians would later say that Eisenhower’s message was to the point: “Full victory — nothing else,” but Strobel’s spouse said later it was about fishing in Michigan, although Eisenhower capped the conversation by asking if the men had properly briefed about their mission.

The General’s son, John, would later recalled that his father would always “talk to troops about things back home, things that were familiar to them. If he found out that someone was from Kansas, he’d talk about cattle and farming, so it’s natural that with Strobel he discussed fishing.” (Susan Eisenhower, How Ike Led, Thomas Dunne Books, 2020; Ch 1, Section 7, Para 83)

Eisenhower tried to reassure the men that they would succeed in their mission, that they had the best training, the best equipment, and the best leadership.

One soldier said: “Hell, we ain’t worried, General. It’s the Krauts that ought to be worrying now!” Another soldier shouted, “Look out, Hitler, here we come!” (Stephen Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890–1952, Volume I, New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 1983; pg. 309)

Another shouted, “Don’t worry about us, Sir. We’re going to whip Hitler!” (Susan Eisenhower, Ch 1, Section 7, Para 82)

As Eisenhower bade the men well and walked away, Val Lauder, a newspaperman who was with him, told friends that Eisenhower had tears in his eyes. (https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2020/06/d-day-and-general-eisenhowers-greatest-decision/)

That night, 822 aircraft, carrying paratroopers or towing the gliders, departed their bases in Britain and headed towards Normandy. Soon they were roaring over the naval force mustering in the Bay of the Seine. It was only a matter of hours before Eisenhower learned how successful the paratroopers would be.

Photographs above: Eisenhower visited the men of the 101st Airborne Division at Greenham Common. Eisenhower was aware that he was sending many of these men to their possible deaths. US National Archives

Above left: General Bernard “Monty” Montgomery interacts with Company Sergeant Major Kelly of Aldershot (of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles), itself part of British 3rd Infantry Division, in the run-up to D-Day. This interaction happened at the battalion’s camp near Portsmouth. This battalion had previously served in one of Monty’s divisions earlier in the war. IWM H 38644

Above right: King George VI speaks to Monty during a visit to 21st Army Group Headquarters on 22 May 1944. IWM H 38734. The shield, which is affixed to the vehicle, marks Monty’s previously victorious North African campaigns: Egypt, Tripolitania, Tunisia and Sicily.

Mast image: Paratroopers of the British 6th Airlanding Brigade look at graffiti chalked on the side of their Horsa glider reading: "The Channel stopped you, but not us. Now it's our turn. You've had your time, you German swinhunds (meaning schweinhunds or swine/bastards)," at an RAF airfield. IWM H 39178