Deception

The destines of the invaders were uncertain and the Allies were not content to leave them further to the vagaries of fate. One of their weapons of choice was the ruse, to prevent the Germans from rushing reinforcements to Normandy.

As the Chinese military strategist, Sun Tzu, wrote nearly 2,500 years earlier: “Hiding order beneath the cloak of disorder is simply a question of subdivision. Concealing courage under a show of timidity presupposes a fund of latent energy. Masking strength with weakness is to be effected by tactical dispositions. Thus one who is skillful at keeping the enemy on the move maintains deceitful appearances, according to which the enemy will act.” (Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Hodder & Stoughton, 2017; Ch 5, loc. 257, 26%)

Strange goings-on began in southern England. At Dover, the shore sprouted elaborate jetties, oil storage tanks, pipelines and anti-aircraft guns – all designed by an eminent architect, Basil Spence. But Spence’s creations were fake, designed to fit the criteria of Operation “Fortitude” – an Allied campaign to simulate a build-up of forces across from Pas de Calais while disguising the real troop concentration in the south of England.

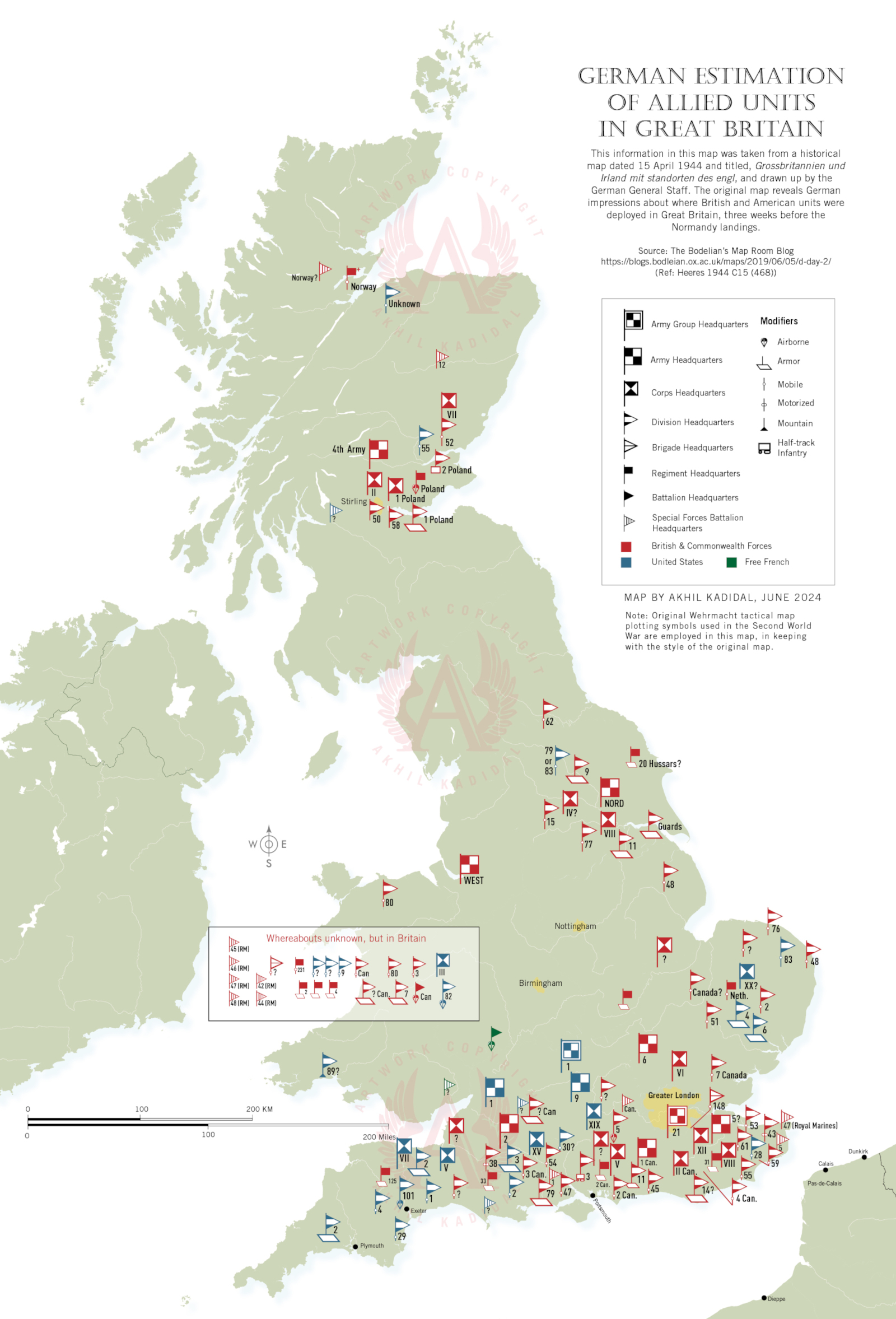

As part of the operation, the Allies placed General Sir Andrew Thorne in command of a fictitious British 4th Army in Scotland, where wireless traffic simulated a British II Corps around Stirling and a British VII Corps around Dundee. But the real jewel was the creation of the First United States Army Group (FUSAG) in southeast England, in the vicinity of the Dover area.

This fabricated unit was placed under the command of US Lt-General George S Patton, one of America’s most famous generals, with an order of battle (all fictitious) even greater than that of the Montgomery’s 21st Army Group which was headed to Normandy.

Equipped with a massive array of dummy landing craft, vehicles, camps, tank-shaped balloons, even cardboard airplanes, the group was aided by the American 303rd Signals Battalion, whose wireless traffic gave the Germans an invaluable stream of false information.

Although treated with much skepticism by the Americans, the threat of this phantom army prompted the Germans to concentrate 15 divisions in the Pas de Calais area. Lieutenant General Max Pemsel, chief of staff of the German 7th Army, said that as of 1 January 1944, Rommel was convinced that the Allied blow would fall on the Pas de Calais area. (Mary Kathryn Barbier, D-Day Deception: Operation Fortitude and the Normandy Invasion, Praeger, 2007; pg 162)

However, by early May, General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff at German High Command told Oberbefehlshaber West (OB West or Western Front HQ) relayed that Hitler had “definite information that Normandy is endangered.” (Barbier, ibid.)

This prompted the withdrawal of several units from the Pas de Calais area to the Cotentin peninsula and to the Caen front. By May 1944, Rommel had come along to the idea that Normandy would be site of the future invasion. (Barbier, ibid.)

Overestimation

But the Germans still massively overestimated the number of Allied divisions in Britain.

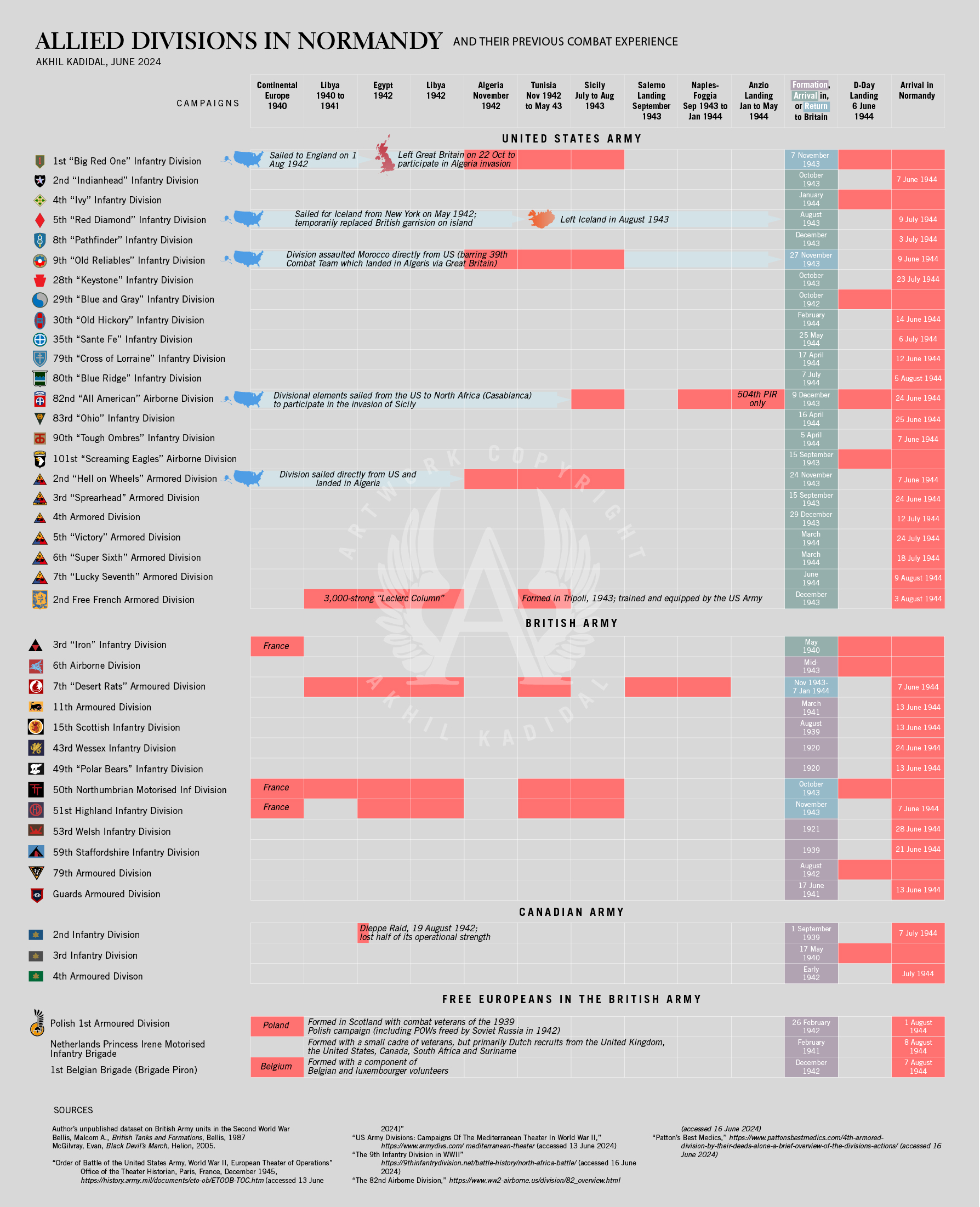

After scattered reconnaissance flights by German in May 1944 it was thought that Allies had available landing craft and shipping to transport 16.5 divisions across the English Channel. German intelligence also thought that Eisenhower had 78 combat-ready divisions under his command (56 infantry, seven airborne and 15 armored divisions). They also believed that the Allies had five independent infantry brigades, independent 14 armored brigades and six parachute battalions. (C P Stacey, The Victory Campaign: The Operations in Northwest Europe 1944-1945, Volume III, Ministry of National Defence, 1960; pg. 60)

In reality, Eisenhower had 38 divisions (22 infantry, four airborne and 12 armored). He also had 16 separate US Army tank battalions, seven independent British armoured brigades, two independent British infantry brigades, and two British Special Forces/Commando brigades which saw action in Normandy.

The German overestimation of Allied combat manpower also had the effect of reinforcing the fictional threat of FUSAG across the English Channel.

Consequently, a 10 July 1944 report from Rommel’s headquarters to OB West, more than a month after D-Day, stated that, “The enemy has at present 35 divisions in the landing area [in Normandy]. In Great Britain another 60 are standing-to, 50 of which may at any moment be transferred to the continent… We shall have to reckon with large-scale landings of the 1st US Army Group in the north for strategic cooperation with Montgomery’s Army Group in a thrust in Paris.”

The Allied ruse had worked. And then there was Lieutenant M E Clifton James.

The Impersonator

A lowly officer in the British Army Pay Corps and an aspiring actor, the greatest role that James ever played was that of impersonating General Montgomery.

As a close physical match for “Monty,” James became part of an elaborate web of deception woven to cloak D-Day. Recruited by British Intelligence after he was seen doing a stage impersonation of the General, James was coached on “Monty’s mannerisms, his sense of dress and brusque speaking style.

On May 25, 1944, came James’ first real test. He was flown to RAF Northolt in Britain to Gibraltar in Churchill’s private airliner, where he met the Governor-General. Talks revolved around “Plan 303,” a fictitious plan to invade the south of France. The information made its way to the Germans. Following on this, James then flew to Algiers where he met with General Maitland Wilson, Allied commander of the Mediterranean Theater of War.

Next followed a jaunt to Egypt where he would stay until well after the Normandy invasion had begun. The British logic was clear: If Britain’s premier military commander was in North Africa, the Germans would not suspect that he was in Britain, planning the invasion. Postwar research found that German generals believed that James was Montgomery, even if they did not believe his reasons for being in North Africa.

Airborne Deceptions

Beyond the long-con of “Fortitude,” a series of decoys and tricks kicked into high-gear on the night of 5 June and early towards the dawn. One of these was the brainchild of a team of scientists under Robert Cockburn.

To decoy the 100 German radar stations dotting the French and Belgian coast capable of picking up the allied invasion fleet as it headed for Normandy, Allied planes began to dump bundles of chaff (or “Window” as it was known then) at low altitude to form a ship-sized cloud that disappeared into the water after spreading out, only to be replaced by another cloud of Window. Most bundles were dropped near the Pas de Calais area.

One of the simulated fleets, codenamed “Taxable,” consisted of eight Lancaster bombers moving towards Le Havre, 50 km (31 miles) northeast of Caen, while the second, codename “Glimmer,” consisted of six bombers moving towards Boulogne, 30 km (18.5 miles) southwest of Calais. The bombers simulated a surface fleet by flying a racetrack pattern about 22 km (14 miles) long at a speed of 290 km/h (180 mph). The crews, meantime, dispensed Window on a precisely set time schedule to ensure that Window clouds advanced at a rate consistent with a naval fleet.

Aircraft with “Mandrel” Jammers accompanied the two “fleets,” and by purposely operating at low power enabled the Germans to penetrate their jamming. The aircraft were also accompanied by small naval launches, towing floats that were in turn affixed with nine-meter (118 ft) long barrage balloons, known as “Filberts.” (Martin Bowman, Confounding the Reich, Pen & Sword, 2004; Ch. 6, Section 14, Para 31)

The balloons carried three-meter (39 ft) diameter radar reflectors that produced radar echoes similar to that of large troop ships. British signal operators onboard the naval launches began to pick up German air patrols on their radars about midnight, but these air patrols for ineffective, for the German pilots were restricted in their movements by being relegated to the French coast.

At a time when the Luftwaffe could have made all the difference by conducting air reconnaissance flights over the port of southern England, it chose not do so. When the deception fleets approached to about 16 km (10 miles) offshore from their targets, smoke screens were set up and sounds of a large fleet in operation were played over big loudspeakers. The Germans were deceived. Elsewhere, RAF bombers released Window and even dummy parachutists – little dolls attached to parachutes that looked like real paratroopers from a distance – which added to the confusion.

The bad weather also played a role in dissuading the Germans that an invasion would materialize.

When the BBC warned the French resistance of the impending invasion by broadcasting the lines from the Paul Verlaine poem: Blessent mon coeur d’une langueur monotone (The violins of autumn wound my heart with monotonous languor), the German 15th Army in the Pas de Calais area went on high alert. (Cornelius Ryan, The Longest Day, Coronet, 1993; pg. 84)

But Rommel’s headquarters at Army Group B did nothing.