The Chindits, the Marauders and the Air Commandos

in 1944

– Orders of Battle and Resources –

3rd INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION

The Chindits were officially known as the “Special Force” or the 3rd Indian Infantry Division, but one should note that title “3rd Indian division” was purely a deceptive title to fool the Japanese. The bulk of the division contained Britons, West Africans, Gurkhas, Burmese and a few Indians in the engineering and service companies.

Virtually a double-strength division, the 3rd Indian had an unprecedented six brigades under its control– each referred to by a nickname. Each brigade had its own headquarters situated near an airfield with a headquarters column in the field.

Commanding Officer (CO)

(1) Major-Gen. Charles Orde Wingate (KIFA 24 March)

(2) Major-Gen. Walter D.A. Lentaigne (From 30 March)

Deputy CO

(1) Maj-Gen. G.W. Symes (Resigned, early April)

(2) Brigadier Derek Tulloch (Replaced Symes but being unpopular with both Symes and Lentaigne, was bypassed in the chain of command. Lentaigne instead preferred Col. Alexander)

Brigadier, General Staff CO (Rear HQ)

(1) Brigadier Derek Tulloch

(2) Col. Henry T. Alexander

GSO 1 (Ground), Chief Operations Officer

(1) Lt-Col. Francis Piggott (Sacked)

(2) Lt-Col. Henry T. Alexander

GSO 2 (Ground), Assistant Operations Officer — Major David Tyacke

GSO 1 (Air), Chief Operations Officer ?

GSO 2 (Air), Assistant Operations Officer — Major Frank Barns

GSO 3 (Air), Liaison Officer to Air Commandos — Capt. Paul Griffin (Jan 1944 to Mar 1945)

Chief Supply Officer — Brigadier Neville Marks

Signals Chief — Colonel Claude Fairweather

Headquarters:

Rear HQ — Gwalior, India

Main HQ — First at Imphal, then at Sylhet, Assam

Launching HQ — Lalaghat

Tactical-Forward HQ — Shaduzup, Burma

The 70th British Division: Of the four primary reasons for the regular army’s hatred of the Chindits, the 70th Division constituted possibly the third. A veteran of the 1942 fighting for Tobruk in North Africa, the division had begun the war as the 7th Division under  Maj-Gen. Richard O’ Conner. Initially held in British Palestine, the division was renumbered as the 6th Division on 3 November 1939 while in Egypt, and although its members expected to see action, none came and the division returned to Palestine. This nonchalant state of affairs continued until June 1940 when the unit returned to Egypt only to be disbanded and its men sent to other units as replacements.

Maj-Gen. Richard O’ Conner. Initially held in British Palestine, the division was renumbered as the 6th Division on 3 November 1939 while in Egypt, and although its members expected to see action, none came and the division returned to Palestine. This nonchalant state of affairs continued until June 1940 when the unit returned to Egypt only to be disbanded and its men sent to other units as replacements.

Reconstituted the next year, on 17 February 1941, the division seemed set to repeat the old pattern of rear-line deployment, but then on October 10, found itself re-designated the 70th Division and transferred to the legendary sea fortress of Tobruk between 13 and 20 October — primarily to relieve the heroic 9th Australian Division which had defended the seaport all that year. In November, the division fought its way out of the fortress and linked up with the rest of the British army, an act that officially broke the Axis siege of Tobruk. But by this act, the unit also passed from being a front-line unit and into a reserve division. In March 1942, it was transferred to far-off India to meet the Japanese threat.

Initially bivouacked at Bangalore in the south for a sustained period of rest, the division became the pride of the armies in India. It was the only fully-trained, completely-equipped British division in the theatre, and when orders came that it was to be broken up to augment the Chindit Force, it generated considerable resentment at General HQ India. It did not help that few of the senior army types trusted Wingate or his eccentric nature.

The other reasons for army anger included what was perceived as a Chindit “poaching” of good men and material for their unconventional, “highly-dubious” endeavor; a general suspicion of all special operations by the straight-laced Indian-British Army leadership (the list of detractors even included the popular General William “Uncle Bill” Slim), and resentment over Wingate’s favor with Churchill, Field Marshal Wavell and other leaders in England — all of which amounted to a fear that the Chindits would overshadow regular army operations against the Japanese in Burma.

It must be mentioned that Wingate also held a bias against the conservative Indian-British Army and Indian troops, whom he termed “second rate” — an unfair estimation considering the outstanding campaign conducted by these men in the recapture of Burma and elsewhere. Arguably, this was another source of friction for William Slim, the commander of the British 14th Indian Army, who took grave exception to Wingate’s opinions about the army.

Meantime, the 70th Division began to reorganize for the role of “long range penetration” on 6 September 1943, relinquishing its units to the 3rd Indian Division or “Special Force” (the Chindits) on October 25th. The divisional HQ ceased to function on that day and the division itself ceased to exist on November 24th.

Events leading to Operation “Thursday”

The first Chindit expedition, Operation “Longcloth” was considered an important breakthrough in strategic thinking. It proved that a war in the densely forested jungles of Burma could be fought and won – contrary to previous notions. In fact “Longcloth” proved so impressive that the Japanese who had long given up the idea of invading India, believing that the jungles beyond the Chindwin River were impassible, began to review to plan their own invasion of India. through those same jungles.

By the end of 1943, armies on both sides of the Chindwin (a defacto border separating the Allies from the Japanese) were content to hold what they had. In contrast, American strategy had taken the offensive – and they wanted to divert as much enemy troops as possible from the Pacific and at the same time, keep China (and her airbases) free to strike at the Japanese homeland. US commanders, notably General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” attempted to achieve this by training and attempting to organize the notoriously corrupt Chinese army for offensive operations. Meantime, they hoped for a campaign from the British who they believed held a large, untapped reserve of mainly Indian manpower.

At the “Quadrant”summit conference held in Quebec in August 1943, future allied military policy was the agenda. The British were under pressure to take offensive action in the Burma theatre. Churchill, with Wingate by his side, persuaded the allied chiefs to embark on a second, larger Chindit offensive. Wingate’s plans were ambitious. His proposal was to airlift several divisions behind Japanese lines. It was a bold plan but curtailed by political squabbles, reduced to include just a single division (albeit a highly-reinforced division) to take part in what would eventually become named as Operation “Thursday.”

At the core of Wingate’s plan was “to insert himself in the guts of the enemy” with the hopeful bonus that the Japanese would not know where they he had landed. This idea had two objectives:

A) Punch deep into enemy lines.

B) Stay there until relieved.

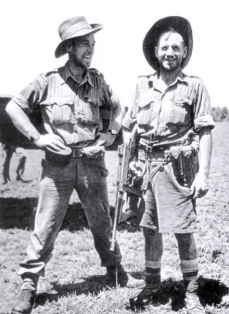

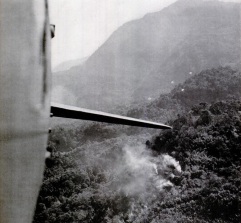

Wingate decided to retain the heart of the British system – using morale and motivation to the fullest – the espirit de corps of the regiment as the building block of his new force. To this end, he used men mainly from General Symes’ British 70th Infantry division, known for its high levels of training and morale, with a core of units staffed by veterans from the original 77th Brigade. But this time, instead of marching into Burma and harassing the Japanese with guerrilla-type raids, the Chindits were to land by glider in jungle clearings and build fortress, complete with artillery support and forward airstrips to bring in supplies and take out the wounded. It was a dramatic new tactic that would have deep consequences.

For a detailed history of the second campaign, click here

—————————————————————————————————————————-

As I go through more of my sources, the order of battle below with its list of commanders may one day be complete. In the meantime, if you have any information that could be of importance, kindly send me a message. Updated – 6 July 2016. (All dates indicated below are by day/month)

—————————————————————————————————————————-

3rd West African “THUNDER” Brigade (Brig. A.H. Gillmore (sacked 18/4), Brig. Abdy H.G. Ricketts)

3rd West African “THUNDER” Brigade (Brig. A.H. Gillmore (sacked 18/4), Brig. Abdy H.G. Ricketts)

6th Bn, Nigeria Regiment (Lt-Col P.G. Day (sacked 17/3 after battalion suffered an ambush), replaced by Lt-Col. Gordon Upjohn)

—- 66 Column (Battalion CO)

—- 39 Column

7th Bn, Nigeria Regiment (Lt-Col. Charles Vaughn)

—- 29 Column (Maj. Charles Carfrae)

—- 35 Column (Battalion CO)

12th Bn, Nigeria Regiment (Lt-Col. Pat Hughes)

—- 12 Column

—- 43 Column

HQ, 7th West African Field Coy – 10 Column

3rd West African Field Ambulance

14th “JAVELIN” Brigade (Brigadier Thomas ‘Ian’ Brodie)

HQ Column – 59 Column

2nd Bn, Black Watch (Lt-Col George Green)

—- 42 Column (Maj. D.M.C. Rose)

—- 73 Column (Battalion CO)

1st Bn, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regt (Lt-Col Pat Eason (ill in May of scrub typhus, died in hospital), repl by Lt-Col. T.J. Barrow)

—- 16 Column (Battalion CO)

—- 61 Column

2nd Bn, Yorkshire & Lancaster Regt (Lt-Col P. Graves-Morris, MC)

—- 65 Column (Maj. B.S. Downward)

—- 84 Column (Battalion CO)

7th Bn, Leicester Regiment (Lt-Col. F.R. Wilford)

—- 47 Column (Battalion CO)

—- 74 Column (Maj. J. Geoffrey Lockett)

54th Field Coy, RE

Medical Detachment

16th “ENTERPRISE” Brigade (Brigadier Bernard E. Fergusson, DSO)

HQ Column – 99 Column (Brigade Major: Maj. J.H. Marriot, MC)

Rear HQ (Lalaghat, India) – 2IC: Lt-Col. F.O. ‘Katie’ Cave

1st Bn, The Queen’s Royal (West Surrey) Regiment (Lt-Col J.F. Metcalf (evac in April), repl by T.V. Close)

—- 21 Column (Metcalf, Maj. Clowes)

—- 22 Column (Maj. T.V. Close → repl by Maj. G.F. Ottaway)

2nd Bn, Leicester Regiment (Lt-Col. Claude ‘Jack’ Wilkinson, DSO (WIA 26/3), Lt-Col H.N. Daniels)

—- 17 Column (Battalion CO, Maj. Dalgliesh, MC)

—- 71 Column (Maj. H.N. ‘Dafty’ Daniels)

51st/69th Royal Artillery (Lt-Col. R.C. Sutcliffe) (Composed of RA personnel)

—- 51 Column (Maj. A.C.S. Dickie)

—- 69 Columns (Battalion CO)

45th Recce Regt (Made from Recce units) (Lt-Col Cumberledge (evac 30/3), Lt-Col. G.H. Astell)

—- 45 Column (Maj. Ron Adams KIA 26/3, Battalion CO)

—- 54 Column (Maj. Varcoe (evac sick), Maj. E. Hennings (KIA))

2d Company, RE

Medical Detachment

23rd Long-Range Penetration Brigade Brigadier (Brigadier Lance ECM Perowne)

(Never joined the Chindits in the field. Was instead used to quell Japanese attackers in the Kohima area.)

HQ Column – 32 Column

1st Bn, Essex Regiment

—- 44 Column

—- 56 Column

2nd Bn, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (Lt-Col. E.W. Stevens, MBE) → Bn fought in the Naga Hills

—- 33 Column (Maj. S.R. Hoyle, MC)

—- 76 Column (Battalion CO, Maj. A.D. ‘Tony’ Firth, DSO) → Known as “The Smugger’s Column”

4th Bn, Border Regiment

—- 34 Column

—- 55 Column

12th Field Company, RE

Medical Detachment

77th “EMPHASIS” Brigade (Brigadier J Michael Calvert)

HQ Column – 25 Column (Brigade Major: Maj. Francis Stuart)

Rear HQ (LZ Broadway) – Bde 2IC: Col. Claude Rome, DSO)

Mixed Field Coy, RE/Royal Indian Engineers

3rd Bn, 6th Gurkha Rifles (Lt-Col. H.A. ‘Boom’ Skone (evac), Lt-Col. Freddie Shaw)

—- 36 Column (Initially both columns commanded by Skone)

—- 63 Column (Maj. Freddie Shaw)

1st Bn, The King’s (Liverpool) Regt (Lt-Col W.P. ‘Scottie’ Scott) (To 111 Bde in May)

—- 81 Column (Battalion CO) → Floater Column at ‘Broadway’

—- 82 Column (Maj. Gaitley)

1st Bn, Lancashire Fusiliers (Lt-Col. Hugh N.F. Christie)

—- 20 Column (Maj. Shuttleworth, Maj. David Monteith, KIA 8/6)

—- 50 Column (Battalion CO)

1st Bn, South Staffords Regiment (Lt-Col. G.P. Richards, MC (WIA 22/3, died in May), Lt-Col. Ron Degg)

—- 38 Column (Battalion CO, Maj. W.A. Cole, MC)

—- 80 Column (Maj. Degg) → Both columns combined in mid-May and evac in July

3rd Bn, 9th Gurkha Rifles (Lt-Col. George Noel → repl. by Lt-Col. Alec Harper) (To 111 Bde in May)

—- 57 Column (Battalion CO)

—- 93 Column (Maj. R.E.G. ‘Reggie’ Twelvetrees)

142nd Commando Coy, Hong Kong Volunteers

Medical and Veterinary Detachments

111th “PROFOUND” Brigade (Brigadier William DA ‘Joe’ Lentaigne – after he was promoted up in March, the brigade was given to Brigadier J.R. ‘Jumbo’ Morris, who was unable to relinquish command of Morrisforce. Therefore, the brigade was commanded in the field by Major John Masters, appointed temporary brigadier, while Morris was its commander on paper)

HQ Column – 48 Column (Brigade Major: Maj. John Masters → repl by Maj. ‘Baron’ Henfry)

Rear HQ:

1st Bn, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) (Lt-Col. William M. ‘Bill’ Henning – to 15 Sept 144)

—- 26 Column (Temp Maj. B.J. ‘Tim/Breezy’ Brennan)

—- 90 Column (Battalion Commander)

2nd Bn, The King’s own Royal Regiment (Lt-Col. A.W. ‘Tommy’ Thompson)

—- 41 Column (Battalion Commander)

—- 46 Column (Maj. Heap)

3rd Bn, 4th Gurkha Rifles (Lt-Col. Ian Monteith)

(Adjutant – Major Bill Towill)

—- 30 Column (Maj. Maurice Deane)

—- 40 Column → Moved to Morris Force (See below)

Mixed Field Coy, RE/Royal Indian Engineers

Medical and Veterinary Detachments

Morris Force (Morrisforce) (Brigadier J.R. ‘Jumbo’ Morris)

4th Bn, 9th Gurkha Rifles (Maj. Morris (transferred), Maj. Russell)

—- 49 Column (Battalion CO)

—- 94 Column (Maj. Peter G. Cane) → Garrison at ‘Broadway’

3rd Bn, 4th Gurkha Rifles

—- 40 Column (Lt-Col. Ian Monteith, KIA)

† This force harassed Japanese forces in the mountain ridges skirting the Bhamo-Myitkyina Road.

DAH Force (Lt-Col. D.C. ‘Fish’ Herring)

This force consisted on 74 men, including Herring, his second-in-command, Captain Lazum Tang and ten Kachins of the 2nd Burma Rifles, Major Kennedy of the Poona Horse, Captain Nimmo of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, a 19-strong detachment from the Royal Corps of Signals under Captain Treckman, nine Chinese of the Hong Kong volunteers, a 27-strong defense platoon from the South Stafford Regiment under Captain Railton, a demolitions expert, Sgt Cockling, an American liaison officer, Captain Sherman P. Joost and lastly, Private Williams, a medic who looked after the sick and the wounded.

BLADETL (Blain’s Detachment) Major ‘Bob’ Blain

Volunteer force of six officers and 60 men (primarily British and West Africans) used for diversion, sabotage and reconnaissance. The group landed in special gliders which were capable of being hoisted back into the air by C-47 Dakotas equipped with snatching gear.

With its West Africans dressed in American uniforms (ostensibly to fool the Japanese), the unit conducted reconnaissance in the Indaw area, before and after Fergusson’s 16th Brigade arrived.

Gliderborne Commando Engineers

Other Units

Royal Artillery

Supporting non-mobile units employed in defending the Chindit Jungle fortresses:

R, S and U Troops, 160th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (All with 25-Pdr cannons)

W,X,Y, and Z Troops, 69th Light Anti Aircraft Regiment(40mm & 12.5mm Hispano cannons)

Divisional Troops

2d Bn, Burma Rifles – Lt-Col. P.C. Buchanan (One section assigned per column except for the 3rd West African Brigade)

219th Field Park Company, Royal Engineers

Detachment 2nd Burma Rifles

145th Brigade Company, RASC

61st Air Supply Company, RASC

2nd Indian Air Supply Company, RIASC

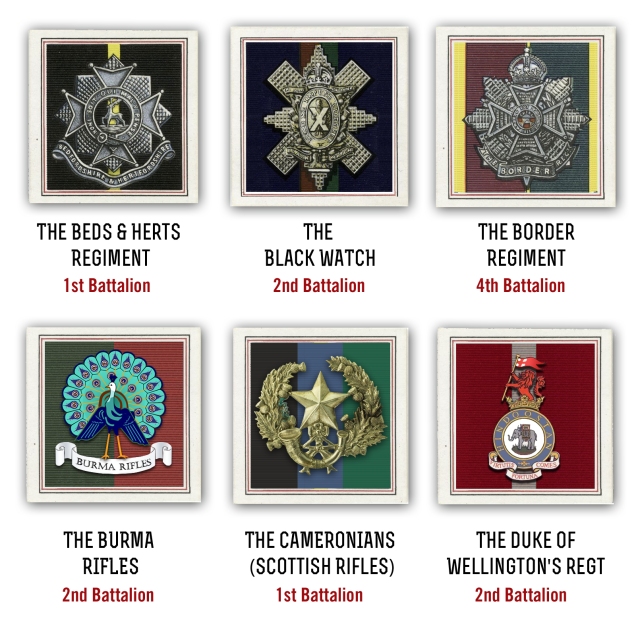

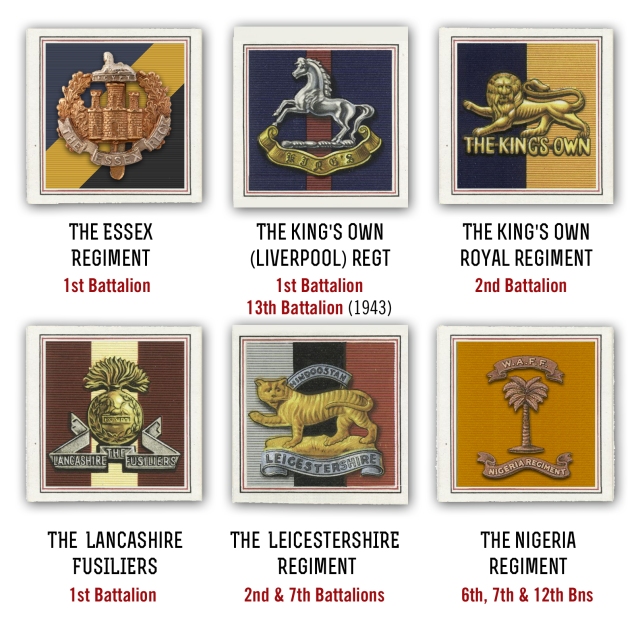

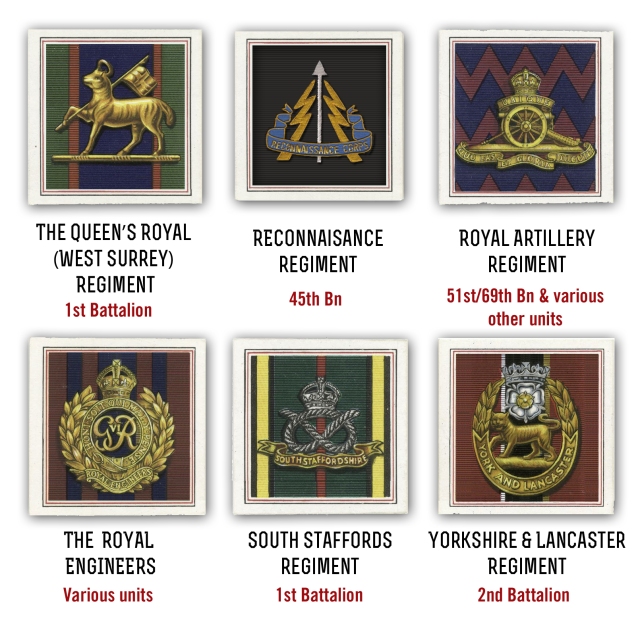

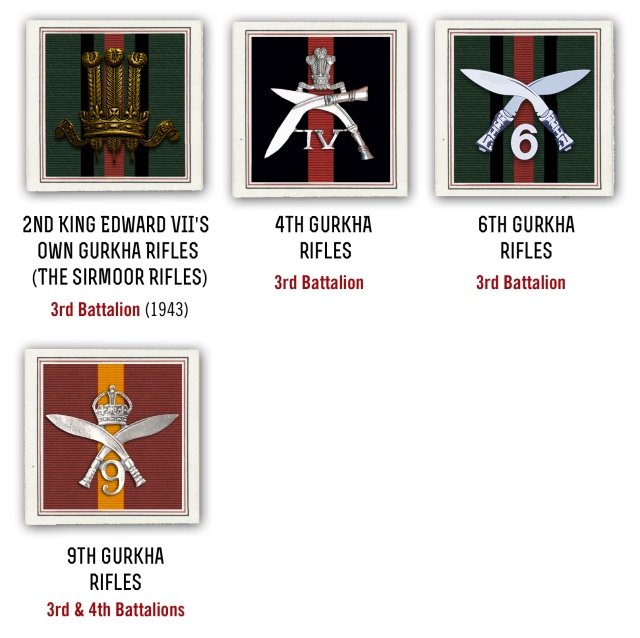

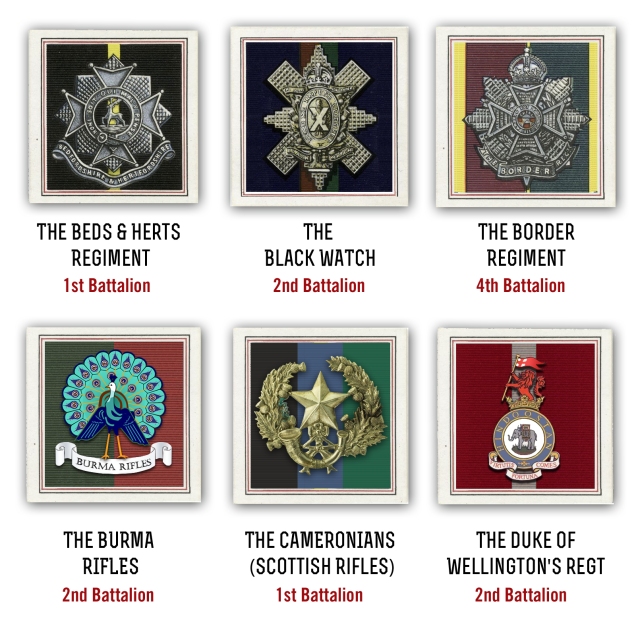

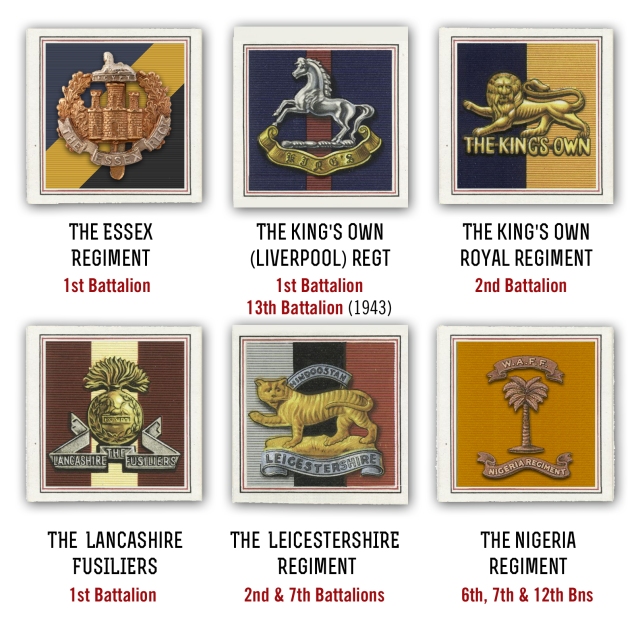

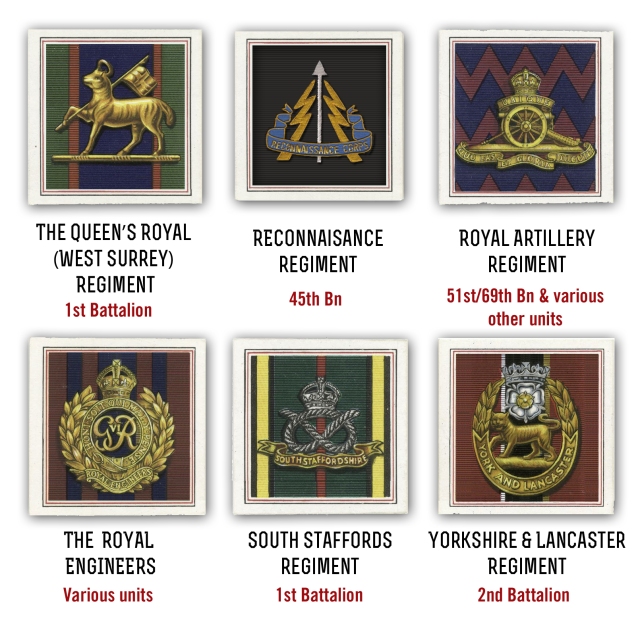

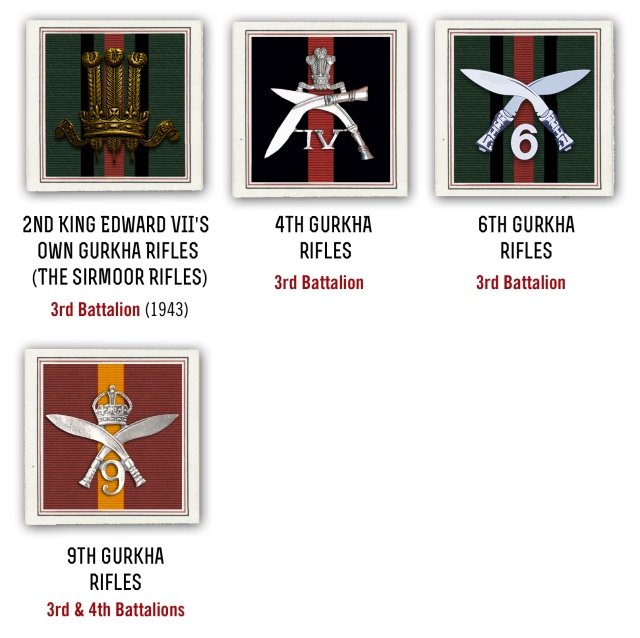

THE REGIMENTS

Source: Almost all of these badges were adapted from vintage Gallagher’s Cigarette cards, printed in the early part of the 20th Century. Digital versions can be found at the New York Public Library’s Online Collection.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Supporting Units

5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), US Army (“Merrill’s Marauders”)

CO — (1) Brigadier-General Frank D. Merrill – 1 Jan to 19 May 1944 (heart attack)

———(2) Col. John E. McCammon – 19-22 May (sacked)

———(3) Brig-Gen. Haydon L. Boatner – 22 May to June 1944 (relieved)

———(4) Col. Charles “Chuck” Hunter – June to 3 Aug 1944 (sent home)

Deputy CO— (1) Col. Charles N. Hunter

—————–(2) Col. John E. McCammon

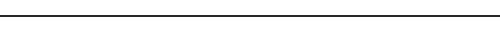

To offset its unglamorous army designation, the unit was unofficially known as Merrill’s Marauders, and joined General Stilwell’s Northern Command after training with Wingate as Chindits from late 1943 to early 1944. It was called “Galahad” by Wingate and the British. The unit possessed a rich diversity of Americans, with men from cities and the country, ranging from Anglo-Saxons to Latins, from Hispanics to Native Americans. Japanese Nisei staffed the intelligence and reconnaissance platoons in good numbers, and the unit’s best sniper was a Sioux Indian.

To offset its unglamorous army designation, the unit was unofficially known as Merrill’s Marauders, and joined General Stilwell’s Northern Command after training with Wingate as Chindits from late 1943 to early 1944. It was called “Galahad” by Wingate and the British. The unit possessed a rich diversity of Americans, with men from cities and the country, ranging from Anglo-Saxons to Latins, from Hispanics to Native Americans. Japanese Nisei staffed the intelligence and reconnaissance platoons in good numbers, and the unit’s best sniper was a Sioux Indian.

Wiped out once in combat, 2,600 fresh, non-Chindit trained replacements were flown in from the United States on May 25 to form a new “Galahad.” Soon, these men too were fighting for their lives at the Burmese town of Myitkyina under General Stilwell’s unbending orders. The survivors were so irate that Stilwell was once lucky to return from the frontline alive. The historian C. Ogburn records one of the Marauders telling an officer: “I had him in my rifle sights. I coulda squeezed one off and no one woulda known it wasn’t a Jap that got the son of a bitch.”

The unit was disbanded on 10 August 1944, a week after the fall of Myitkyina. Only 130 men had avoided becoming casualties out of the original 2,997.

H Force (Col. Charles N. Hunter)

≡ 1st Battalion – Red & White Combat Teams (Lt-Col. William Osborne)

≡ 150th Chinese Regiment

M Force (Lt-Col. George McGee Jr.)

≡ 2nd Battalion – Blue & Green Combat Teams (Lt-Col. George McGee Jr)

K Force (Col. Henry L. Kinnison Jr. (Died))

≡ 3rd Battalion – Khaki & Orange Combat Teams (Lt-Col. Charles Beach)

≡ 88th Chinese Regiment

1st Air Commando Group, United States Army Air Force

CO — (1) Col. Philip C. Cochran – Nov 1943 (officially from 29 Mar) to 20 May 1944

———(2) Col. Clinton B. “Clint” Gaty – 20 May 1944 to 26 Feb 1945 (MIA)

Deputy CO— Lt-Col. John R. Allison – November 1943 to 20 May 1944

Formed under orders from U.S. Army Air Force chief, General “Hap” Marshall, this unit first came into existence as the top-secret Project 9 in 1943, specifically formed to support British long-range sorties into Burma. Later it became known as the 5318th Provisional Group in December 1943 and under this title, took part in Operation “Thursday” airlifting and supporting Wingate’s troops in Burma from March 1944. Yet, before the month was out, another change of title had occurred and the unit officially became known as the 1st Air Commando. Its motto, “Anyplace, Anytime, Anywhere” was lifted from a message sent by Wingate endorsing his support for the group and its men. Carried over in the decades after the war, this is currently the motto of U.S. Special Operations Command.

Formed under orders from U.S. Army Air Force chief, General “Hap” Marshall, this unit first came into existence as the top-secret Project 9 in 1943, specifically formed to support British long-range sorties into Burma. Later it became known as the 5318th Provisional Group in December 1943 and under this title, took part in Operation “Thursday” airlifting and supporting Wingate’s troops in Burma from March 1944. Yet, before the month was out, another change of title had occurred and the unit officially became known as the 1st Air Commando. Its motto, “Anyplace, Anytime, Anywhere” was lifted from a message sent by Wingate endorsing his support for the group and its men. Carried over in the decades after the war, this is currently the motto of U.S. Special Operations Command.

The 1st Air Commandos largely left the Chindits on 20 May 1944 and were disbanded on 3 November 1945. It was later reformed in the US on 18 April 1962 as the 1st Special Operations Wing.

13 x C-47 Dakota, 12 x C-46 Commando Transports (CO – Maj. William T. Cherry)

12 x B-25H Mitchell medium bombers (CO – Lt-Col. Robert T. Smith)

30 x P-51A Mustang Fighter-bombers (CO – Lt-Col. Gratten “Grant” Mahony)

100 x L-1 and L-5 “Grasshopper” Light planes (CO – Maj. A. Paul Rebori (Sacked), Lt-Col Clinton B. Gaty)

10th Jungle Air Rescue Detachment: 6 x Sikorsky YR-4 Helicopters (top-secret, early machines, also under Gaty’s command)

Glider Group (Capt. William H. Taylor Jr.) – Originally with 225 Waco CG-4A Gliders

After the September 1944 Reorganization, the Air Commando had this form:

5th & 6th Fighter Squadrons: P-47 Thunderbolts & P-51 Mustangs

164th Liaison Squadron: C-46 Commando

165th Liaison Squadron: C-46 Commando

166th Liaison Squadron: C-46 Commando

319th Troop Carrier Squadron: C-47 Dakotas

72nd, 309th & 326th Aerodrome Squadrons

284th & 285th Medical Dispensaries

Eastern Air Command

Supply Aircraft

900th Airborne Engineers Aviation Company, US Army

CO — (1) Captain Patrick Casey (KIA 5 March 1944)

Deputy CO— Lt. Robert Brackett

The 900th Airborne Engineers, with a strength of only 4 officers and 124 enlisted men, would carry out five, separate glider landing missions during the course of Operation “Thursday,” apparently earning them the privilege of having made the most glider-borne landings of any glider-borne unit of World War II. The 900th participated in the landings at all the Chindit strongholds: Broadway, White City, Aberdeen, Chowinghee and Blackpool.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

CHINDIT ORGANIZATION

The column was the main unit and all operations were column based (the term column was used literally because all personnel moved through the jungle in a single file). Each battalion had two columns, one commanded usually by the battalion commander and the other by his second in command. Each column had between 400-500 men.

Each column was composed of:

One company with four or five Rifle Platoons

One or two Heavy Weapons Platoons (each with two Vickers MMGs, two 3-Inch Mortars, one Flamethrower and two anti-tank Piats)

One Commando Platoon (with demolition and booby-trap experts)

One Recce Platoon (with a British officer commanding Burma Rifles-Karen and Kachin tribesman)

Plus assorted Royal Air Force controllers, sappers, signalmen and medical detachments.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Acronyms & Abbreviations:

2IC – Second-in-Command

Bn – Battalion (In the British Army, basic combat unit capable of independent action)

CO – Commanding Officer

Coy – Company

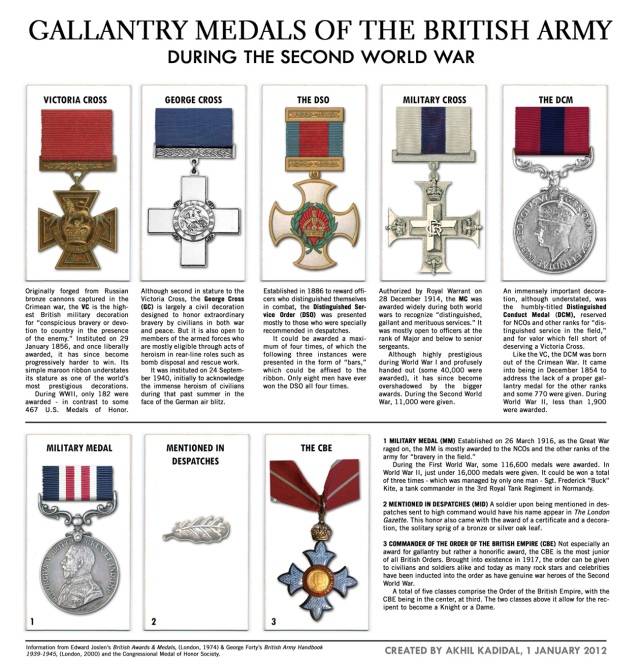

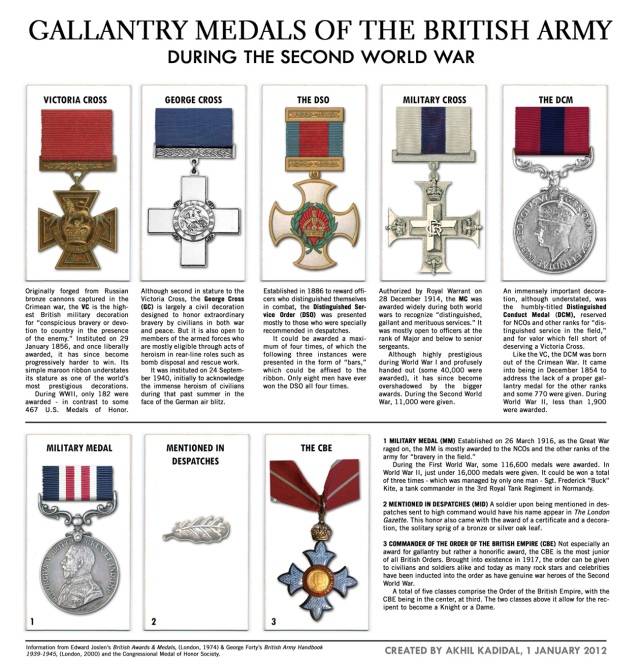

DSO – Distinguished Service Order (Decoration)

Evac – Evacuated from Burma. Relieved of command.

KIA – Killed in action

KIFA – Killed in Flying Accident

MC – Military Cross (Decoration)

RA – Royal Artillery

RE – Royal Engineers

Regt – Regiment (In British Army, purely an administrative formation)

Repl – Replaced

RIASC – Royal Indian Army Service Corps

WIA – Wounded in Action

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Sources for all Chindit writing on this site:

ALLEN, Louis, Burma — The Longest War, London: Phoenix Press, 1984.

ANGLIM, Simon, Orde Wingate and the British Army, 1922-1944, London: Chatto & Pickering, 2010.

ASTOR, Gerald, The Jungle War, Wiley, 2004.

BAINES, Frank, Chindit Affair, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2011.

BIDWELL, Shelford, The Chindit War: Stilwell, Wingate and the Campaign in Burma: 1944, NY: Macmillan, 1979.

BIERMAN, John & Colin Smith, Fire in the Night: Wingate of Burma, Ethiopia and Zion, NY: Random House, 1999.

CALLAHAN, Raymond, Burma 1942-1945, London: Davis-Poynter, 1978.

CALVERT, Michael, Prisoners of Hope, London: Leo Cooper, 1971.

‘——————–‘ Fighting Mad, Norfolk: Jarrolds, 1964.

‘——————–‘ The Chindits, NY: Ballantine, 1971.

CHINNERY, Philip, Wingate’s Lost Brigade, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2010.

CLARKE, Peter, The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire, London: Penguin, 2007.

DIAMOND, Jon, Stilwell and the Chindits, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2014.

‘————‘ Chindit vs Japanese Infantryman, London: Osprey, 2015.

FERGUSSON, Bernard, Beyond the Chindwin, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2009.

‘—————‘ The Wild Green Earth, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2015.

KIRBY, S. Woodburn et al. , History of the Second World War: War Against Japan, London: HMSO, 1957

MARSTEN, Daniel P., Phoenix from the Ashes – The Indian Army in the Burma Campaign, NY: Praeger, 2003.

MASTERS, John, The Road Past Mandalay, London: Cassell, 2012.

McLYNN, Frank, The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942-45, Yale University Press, 2011.

MOREMAN, Tim, Chindit 1942-45, Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

MORTIMER, Gavin, Three Daring Dozen: 12 Special Forces Legends of World War II, London: Osprey, 2012.

NESBIT, Roy Conyers, The Battle for Burma, London: Pen & Sword, 2009.

OGBURN, Charlton, The Marauders, 1960

OWEN, Frank, The Campaign in Burma, London: HMSO.

ROMANUS, Charles and Riley Sunderland, Stilwell’s Command Problems, 1953.

REDDING, Tony, The War in the Wilderness, The History Press, 2015.

ROONEY, David, Mad Mike — A Life of Brigadier Michael Calvert, London: Pen & Sword, 2007.

STIBBE, Philip, Return from Rangoon, London: Pen & Sword, 1997.

SYKES, Christopher, Orde Wingate, NY: World Publishing Company, 1959.

THOMAS, Andrew, Spitfire Aces of Burma and the Pacific, Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

THOMPSON, Julian, Forgotten Voices of Burma, London; Erbury Press, 2009.

THORBURN, Gordon, Jocks in the Jungle, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2012..

TOWILL, Bill, A Chindit’s Chronicle, iUniverse, 2000.

TUCHMAN, Barbara, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, NY: Grove Press, 2001.

WAGNER, R.D. Van, Any Place, Any Time, Any Where, Altgen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1998.

WEBSTER, Thomas, The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theatre in World War II, NY: Harper Collins, 2004.

YOUNG, Edward, Air Commando Fighters of World War II, North Branch, MN: Specialty Press, 2000.

7th Leicestershire Regimental War Diary, The National Archives, WO 172/4900 (Unearthed by Hugh Vaugh)

Captain P. Griffin, IWM Museum of Records, PP/MCR/221 PG/1 ND (ca. 1970’s)

WEBSITES

1. Chindit Chasing, Operation Longcloth 1943 Website:

Interesting original research and a good collection of photographs collected by Steve Fogden pertaining to the 1943 expedition. Well worth a visit if you wish to know more of some of the men who participated in the 1943 campaign. Web address at: http://www.chinditslongcloth1943.com/index.html (Accessed 22 December 2011)

2. The Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment Good information on the Queen’s Regiment during the 1944 expedition. Look for Chapter 5. (Accessed 25 December 2011)

3. 2nd Yorks & Lancs War Diary, 1944 (Accessed 26 December 2011)

4. The British Military History Website: A good collection of information, orders of battle and other war research compiled by Robert Palmer, with an emphasis on the Burma campaign. (Accessed 4 January 2012)

5. The Chindits Society

The society was established in 2015 to connect the families of Chindits, researchers and historians with an interest in the Burma campaign. The aim of the society is to champion and project the history of the Chindits through “presentations and educational initiatives, assist families and other interested parties in seeking out the history of their Chindit relative or loved one, gather together and keep safe Chindit writings, memories and other materials for the benefit of future generations, ensure the continued well-being” of Chindit veterans and “promote fellowship between members.”

Web address at: http://thechinditsociety.org.uk/ (Accessed 2 April 2017)

BY AKHIL KADIDAL

BY AKHIL KADIDAL