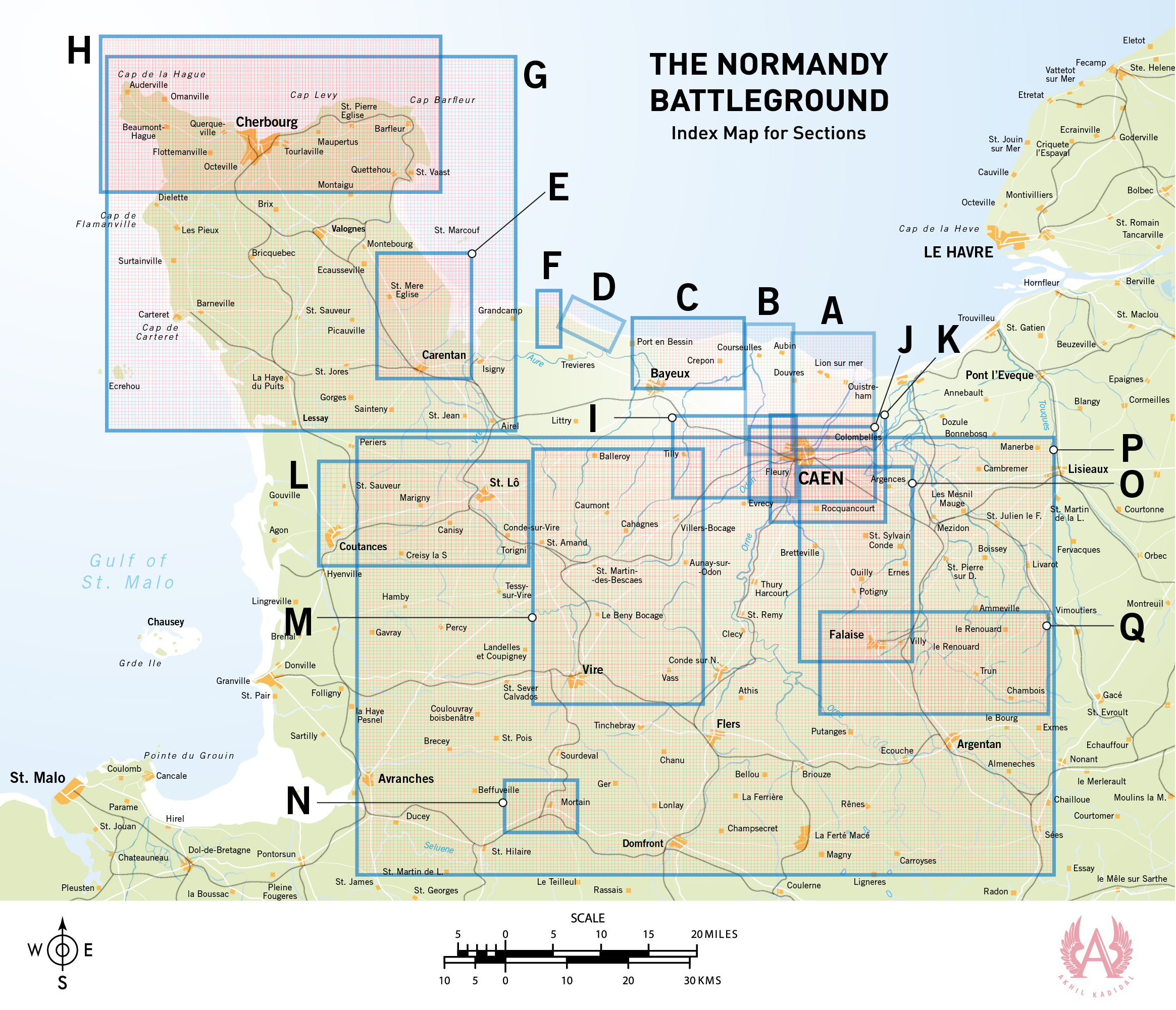

Mapping the Ardennes offensive proved much arduous than my earlier work on Normandy and D-Day.

Admittedly, I knew little about the Ardennes, cloaked as it was, under a tangle of oak, willow, conifers, poplar and beech. What I did know about this great campaign came from scattered readings and for having seen the great 1965 turkey The Battle of Bulge, the significantly better Battleground (1949), and the two-odd episodes of Band of Brothers which portrayed US airborne at the besieged market town of Bastogne.

Part of the challenges is that the landscape of the Ardennes is a difficult place to wrap the mind around, populated as it is with places with impossible names like Houffalize, Foy, Soy, Wiltz, Champs, Saint-Vith, La Gleize, the vaguely wookie-sounding Neiderwampach, Sibret, Butgenbach and a rather pleasant-sounding village named Bra.

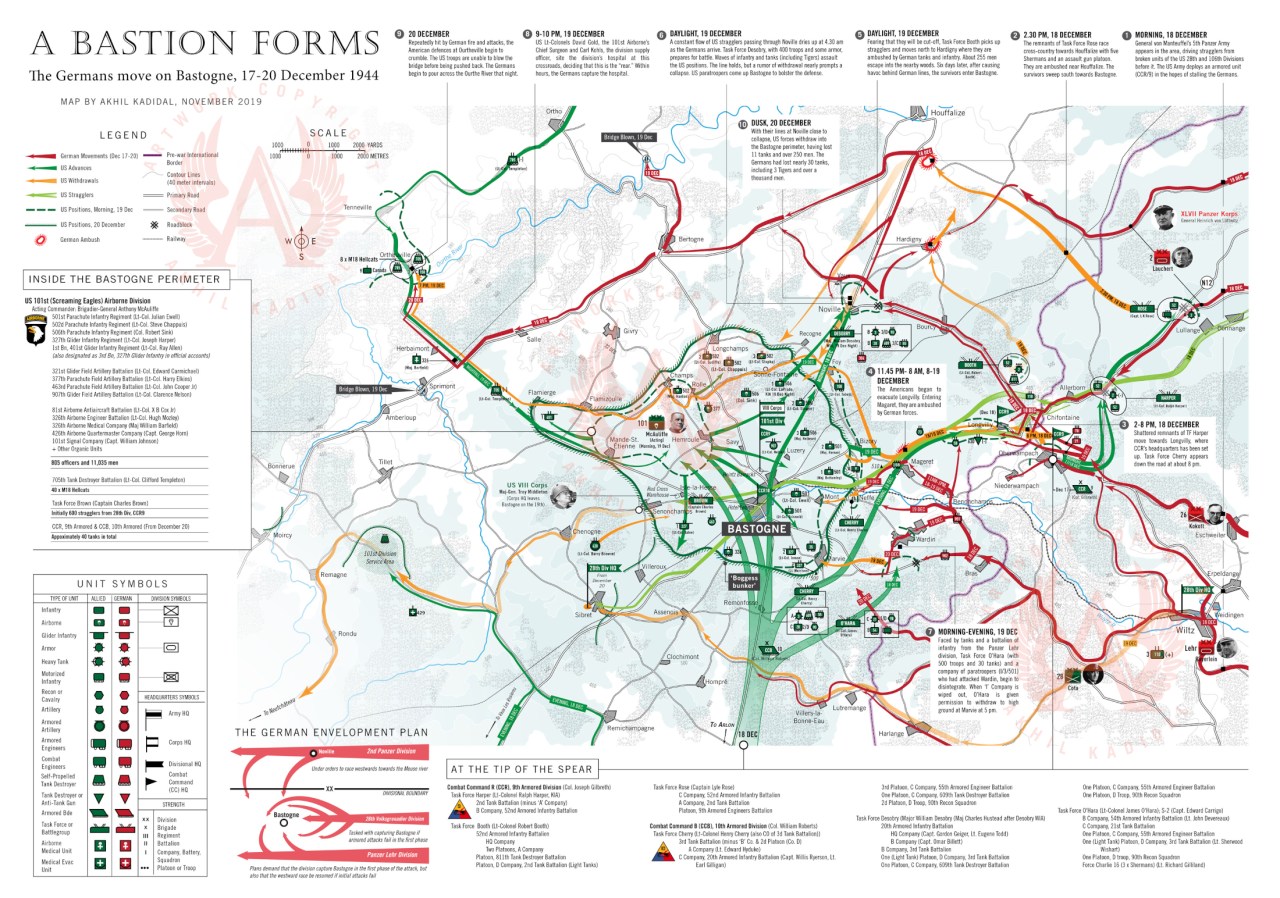

The battles here were monstrous; the brainchild of a despot grasping at straws for a last victory which he believed would reverse the course of the war. However, the finer details of the battle contain an almost supernatural quality: of phantom, snowsuit-clad Germans passing in an out of US lines, of American paratroopers holding frozen ground against titanic German tanks appearing of the mist, of foxlike English-speaking Germans sowing discord behind the lines, of diehard SS commandos wielding captured US Army equipment and uniforms to punch through Allied lines and a fog which hung like a pall for the first nine days of the battle.

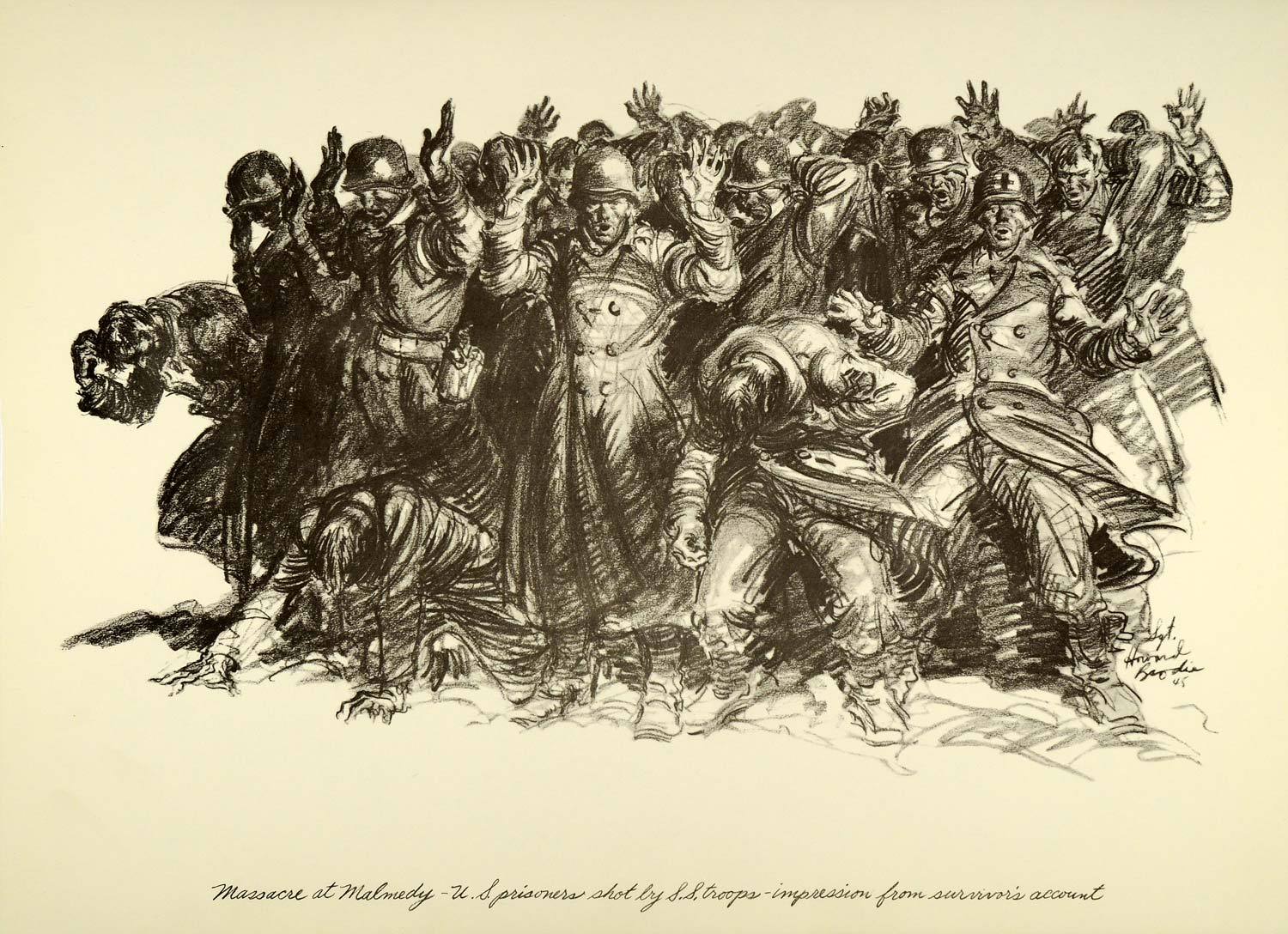

Yet, the alien, hard edges of the Battle of the Bulge are softened somewhat by the pop-culture icons who found themselves in the midst of this struggle — men like the late, affable actor Charles Durning, who possibly survived an SS war crime outside the town of Malmedy, and the author, Kurt Vonnegut of Indianapolis, who, as a member of the green US 106th Infantry Division, fell into the German bag after his regiment was overrun by swarms of Teutonic armor and infantry.

This, I suspect comes to down to our human need to identify something familiar out of the monochromatic visions which emerge from literature and photography. Arguably, cartography is one way to cut through this hermetic barrier. Words may have the ability to evoke powerful scenes, but maps have the power to crystallize text onto a landscape we can visualize in our mind’s eye.

—————

The initial set of three maps took over 30 days to create. Several contemporary books were consulted to figure out how events transpired, including Antony Beevor’s Ardennes 1944, which proved to be singularly useless. In the end, I went back to the original sources: US Army historical documents, manuscripts, dispatches and books including Hugh Cole’s excellent The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge (US Army, 1965).

The Front Explodes

Allied optimism that the war would be over by the Christmas of 1945 was nearly quashed as Christmas approached and the war in Europe looked as though it had no immediate end in sight. The US First Army settled to rest and regroup in the Ardennes Forest in Belgium, an area considered as being a relatively quiet sector of the front. Many of its units were in strung-out shape after enduring relentless combat since the Normandy campaign. But in what was probably the greatest intelligence lapse by the Allies in the war, the Germans were able to assemble, in secret, three entire armies (or over 275,000 men) along the 60-mile long Ardennes front.

The Life and Death of Kampfgruppe Peiper

Events of the 1965 film The Battle of the Bulge largely depicted the movement west of the 1st SS Panzer Division, which had orders to reach to the Meuse River. In real life, the SS was badly delayed by the inability of other units to clear the way – a problem compounded by poor roads which were in no state to support an armored advance. On several occasions, commanders reported mud coming up the decking of tanks.

As the pressure mounted, the SS began to act on an order supposedly handed down from high command, instructing units not to take prisoners, lest they slow down the momentum of the advance. A series of atrocities by SS troops ensued, particularly by Kampfgruppe Peiper, led by an ambitious young veteran of the Russian front, 29-year-old Joachim Peiper.

Among the evocative photographs to come out of the Battle of the Bulge were these two images. Here, two paratroopers of the US 82nd Airborne Division bring a young SS captive in at the point of a Tommy gun. These pictures were taken at Bra, Belgium on December 24, 1944. (Both photographs taken by the Associated Press)

Sgt. Howard Brodie’s depiction of how the “Malmedy Massacre” went down.

Sgt. Howard Brodie’s depiction of how the “Malmedy Massacre” went down.

The Bastion

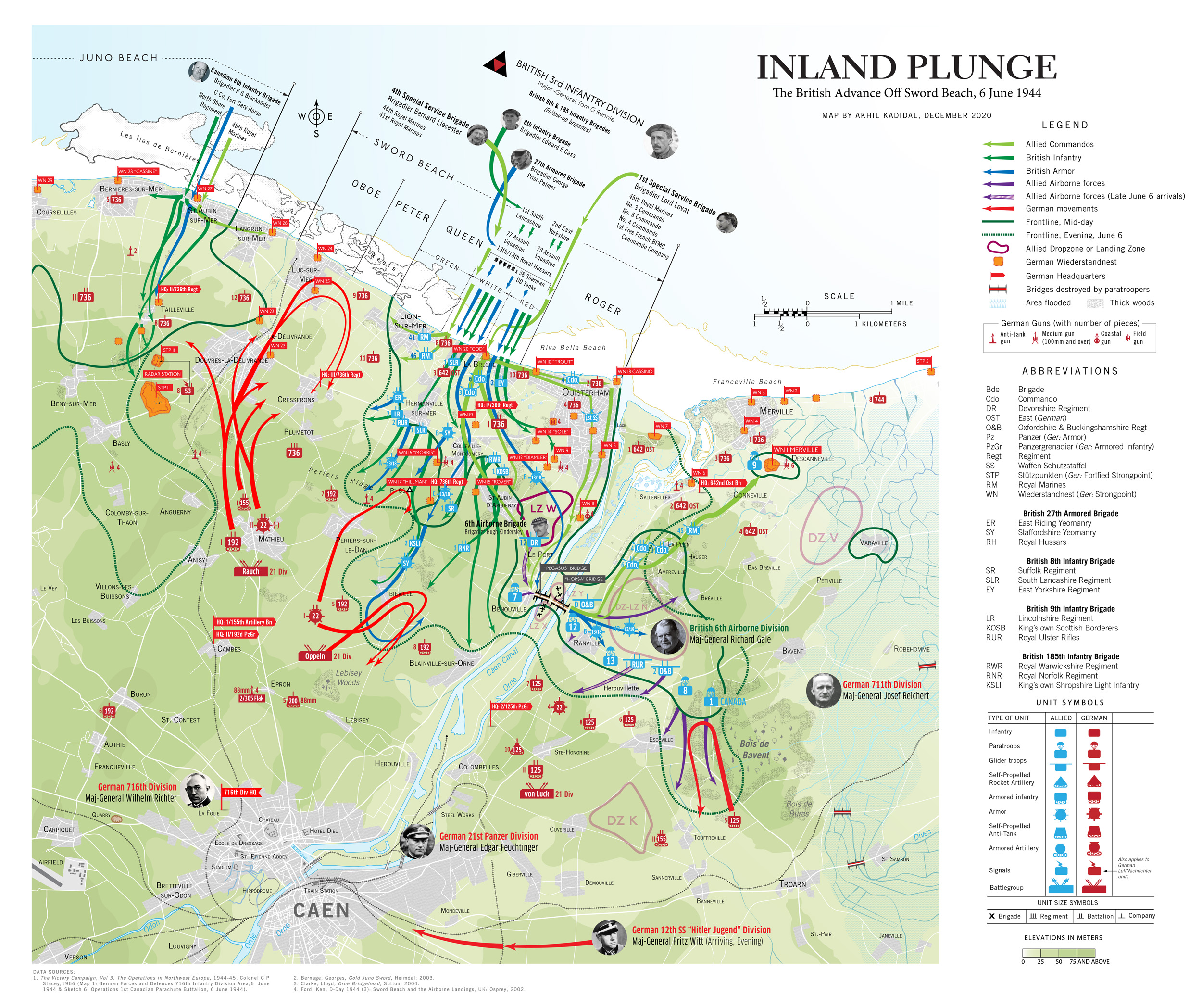

As the Germans swept deeper into the Ardennes, the Belgian town of Bastogne, occupying a key position on the rail and network in the region, came under threat. Bastogne was nearly undefended until the 48th hour of the German offensive. In desperation, the Americans rushed a tank unit (Combat Command R from the 9th Armored Division) to stall the incoming Germans until reinforcements could be pushed into Bastogne. The only other units available were paratrooper divisions recovering from an abortive campaign in Holland that September. The US 101st Airborne Division was alerted to advance into the sector, but being a parachute division, it had no attached armor and a grave shortage of bazookas.

A second tank force (this time from the 10th Armored Division) also raced to defend Bastogne. By dusk on the 19th, the area around Bastogne was embroiled in combat. By December 22, American troops within the Bastogne perimeter realized that they were surrounded. Meantime, the Germans, torn between their desire to stay on course towards the Meuse River and their inclination to nullify Bastogne, mounted a series of penny packet attacks against the perimeter which achieved little and wasted valuable time.

A group of paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division get some hot chow near the frontline. The discovery of a large Red Cross warehouse within the Bastogne perimeter early in the siege, allowed the besieged paratroopers the luxury of hot pancakes on most mornings. (Corbis)

A group of paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division get some hot chow near the frontline. The discovery of a large Red Cross warehouse within the Bastogne perimeter early in the siege, allowed the besieged paratroopers the luxury of hot pancakes on most mornings. (Corbis)