How this research began…

I do not consider myself an expert on the “Battle of the Bulge.” The battle is dense and eventful. But I thought I knew enough about the Ardennes offensive to elevate me above the rank of battle hound. Then I read Alex Kershaw’s “The Longest Winter” and discovered the actions of the Intelligence & Reconnaissance Platoon of the 394th Infantry. As with some of my work, this post is centered around a map of the engagement. During the course of the research, I discovered that two of the GIs (PFC Bill James of White Plains (NY) and PFC Risto Milosevich of Los Angeles (CA) were students of my alma mater, Tarleton State (Texas A&M).

A shortage of manpower in the US military at the twilight of World War II forced the army to transfer some of its best and brightest college-educated draftees who were training to become technical experts and officers to frontline units in 1944 as enlisted personnel.

As members of the US Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), the draftees were to be employed as high-grade technicians and specialists. However, on 1 April 1944, many were reassigned to infantry, airborne, or armored units. Eighteen such men found themselves in a so-called Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon of the US 394th Infantry Regiment in the European Theater of Operations, in the winter of 1944.

Isolated, in a forward position in eastern Belgium, amid snowy, near sub-zero conditions , the platoon found itself snarled in a maelstrom of combat during the opening blows of what would become known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

Isolated Location

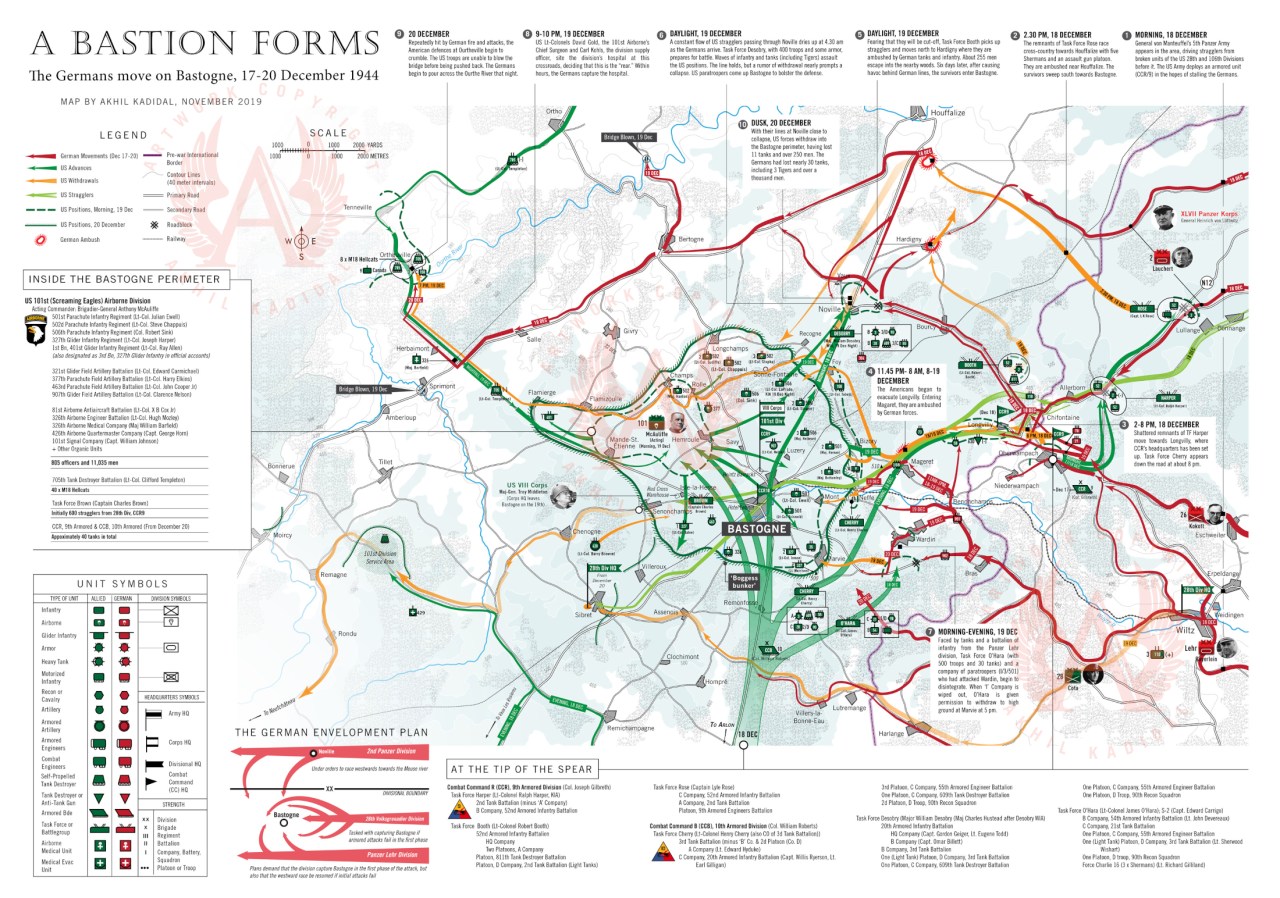

The 394th Infantry Regiment’s I&R Platoon had been posted to an unremarkable hilltop overlooking the Ardennes village of Lanzerath, a few thousand yards from the German frontier on 10 December 1944. Like in the rest of the Ardennes Forest, the platoon’s deployment was regarded as being in a “quiet sector” with scant presence of the hostile German military.

The core role of I&R Platoons in the US Army was to gather detailed information about enemy forces and the terrain in locations that US Arm rifle companies and battalions could not easily access. But in being posted to Lanzerath, the 394th’s I&R Platoon was also expected to fulfill another, more critical role: plugging a gap in the US lines.

The platoon’s parent unit, the US 99th Infantry Division, was a rookie to the wilds of the western European campaign. Known later as the “Battle Babies”, the division arrived on the continent on 6 November 1944, having missed the Normandy campaign and the subsequent Allied breakout across France. Posted to the Ardennes, the division’s inexperience was exacerbated by the fact that it was forced to string its three infantry regiments (393rd, 394th and 395th) out across a 25-mile front, along forest-covered hills.

US army doctrine stipulated that a infantry battalion could cover 800 yards of a frontline. But the 99th’s nine infantry battalions were each covering between 830-1,000 yards. This made it near impossible for US patrols to cover the gaps.

By 14 November, all of the 99th’s battalions and companies were on the frontline barring the 3d Battalion of the 394th Infantry, which was held in a divisional reserve near the boundary with US V and VIII Corps, near the so-called “Losheim gap”, a particularly thinly held part of the frontline.

With only two battalions under his command, Colonel Don Riley of the 394th Infantry Regiment, tried to plug potential holes in his perimeter with small units. One worry was the village of Lanzerath which commanded a road leading westwards, deeper into American lines. The village was the responsibility of the neighboring US Army units such as VIII Corps and the US 14th Cavalry Group.

However, the 394th Infantry lacked combat troops to occupy the village in force and so Riley employed the I&R platoon to provide advanced warning of a German advance or attack in the area. In command of the 394th’s I&R Platoon was First Lieutenant Lyle Bouck Jr, just 20 years old but not an ASTPer. Instead, he was a pre-war army volunteer who had risen through the ranks to become an officer.

“Our I&R Platoon was ‘temporarily’ moved into the resulting gap with orders to investigate and report any observed enemy activity,” a former platoon member, Private G Vernon Leopold, told US Congress in 1981.

The platoon’s location at Lanzerath occupied a veritable no-man’s land between two US Army Corps.

Lanzerath itself was unremarkable, having fewer than ten houses with wooden framework construction that could not withstand enemy fire. However, the village was situated about 300 yards south of a key road junction that connected Buchholz Station to the town of Losheimergraben. Northwest of Losheimergraben lay a major road network which would become a primary route of advance for the German Sixth Panzer Armee (Tank Army) during Operation “Wacht am Rhein” (The Watch on the Rhine) which would go down in the annals of history as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

The Sixth Panzer Armee was under an old veteran, SS Oberst-Gruppenfuhrer (General) Josef ” Sepp” Dietrich who intended to use the road network to reach the Belgian city of Liége.

As night fell on western Europe on 15 December, neither Lt. Bouck nor his men suspected that they had an engagement with history in the morning.