Most of these photographs came from specific collections. Some are refreshingly new — some I hadn’t seen until recently. Unless mentioned otherwise, all photographs are from 1944. If you have a photo that you would like to contribute, kindly e-mail it to me. All photos will be appropriately credited. Numbers indicated in brackets below are Imperial War Museum reference numbers.

Most of these photographs came from specific collections. Some are refreshingly new — some I hadn’t seen until recently. Unless mentioned otherwise, all photographs are from 1944. If you have a photo that you would like to contribute, kindly e-mail it to me. All photos will be appropriately credited. Numbers indicated in brackets below are Imperial War Museum reference numbers.

The Calvert Collection

Brigadier Mike Calvert (far left) with Lt-Colonel Freddie Shaw and Major James Lumley (right) in the ruins of Mogaung town. Driven to the breaking point by the U.S. Lt-General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell (incidentally, well portrayed by Robert Stack in Steven Spielberg’s movie 1941), Calvert led out the surviving Chindits, badly emaciated by disease and heavy casualties.

Major Lumley’s daughter is the British actress, Joanna Lumley, who famously starred in the Pink Panther series and on television. (MH 7288)

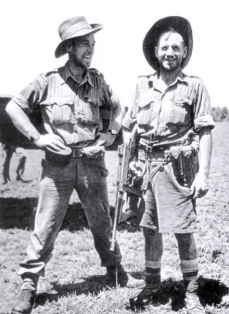

(LEFT) Two survivors from the first Chindit expedition. The expedition was the first Allied success in the campaign for Burma after a disastrous defeat the year before — witness to the British Army’s greatest retreat in history. On the left is Regimental Sgt-Major William Livingstone (MC) and Company Sgt-Major Richard M. Cheevers (DCM), both of Column 8. (RIGHT) A Chindit flamethrower operator aims his No. 2 Mk II weapon. Nicknamed the “Lifebuoy” for its unique round shape which aided maximum gas pressure, the weapon had a maximum range of 40 yards and fuel for only a ten second sustained burst. The flamethrower was the one infantry weapon feared greatly by the Japanese – understandably so.

(LEFT) Wingate (holding cane) with Major R.B.G. “George” Bromhead, planning the first Chindit expedition from his headquarters in the Imphal Golf Club. Success here would elevate the eccentric Wingate to that of a mythical figure. (RIGHT) Two weary Chindits with a supply-carrying mule. Most of the pack mules had their vocal cords cut to to keep them silent in the field – an act that blanched many of the Chindits. (SE 7910)

A batch of Chindit replacements gather their arms and mules at a fortress airfield.

A batch of Chindit replacements gather their arms and mules at a fortress airfield.

(LEFT) Wingate (in pith helmet) briefs the C-47 Dakota pilots of the U.S. 1st Air Commando at Sylhet in Assam. Immediately behind him is one of the Air Commando leaders, Lt-Col. Philip Cochrane (wearing cap). (MH 7877) (RIGHT) The attackers inspect latest intelligence at Lalaghat. From right — Brigadier Tulloch, Wingate, Calvert, RAF Air Marshal Johnny Baldwin, Lt-Colonel Scott, US Lt-Colonel John Alison. Rest unknown. (MH 7884)

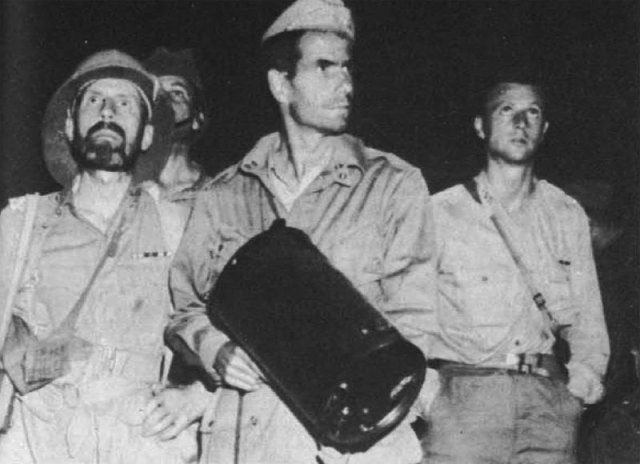

(LEFT) Last minute intelligence showed that tree trunks had blocked a landing field codenamed “Piccadilly.” Despite concerns that the Japanese might have caught news of the imminent airborne landings, Wingate decided to proceed with the operation, with “Piccadilly” crossed off the list as a feasible landing zone. The trees were later discovered to have been felled as part of a routine logging operation. (RIGHT) The night of the assault, just before take-off. From left: John Alison, Calvert, Captain George Borrow (Wingate’s Aide-de-Camp), Wingate, Scott and Calvert’s Brigade Major, E. Francis Stuart. Three of the men would be dead before the year was out: Wingate and Borrow in an air crash that March, and Stuart, by battlefield-contracted tuberculosis in July. (MH 7873)

(LEFT) Maj-Gen. W.D. “Joe” Lentaigne (on left) with the tough and much-respected Brigadier Henry T. Alexander at headquarters. Alexander would go on to become one of eight Chindits to reach the exalted rank of Major-General. (RIGHT) A Gurkha section walks at “Broadway.”

(LEFT) An aerial view of “Broadway,” a fortress carved out of the heavy jungle. (RIGHT) A heavy weapon section at the perimeter of a Chindit jungle airbase, probably at “White City.”

(LEFT) A British 40mm AA crew at “Broadway.” (RIGHT) Lancashire Fusiliers from the Commando Platoon of 50 Column at “White City.” The man in front seems to bear a passing resemblance to the present-day American actor, Dylan McDermot.

Calvert’s final war chapter. After the Chindits were disbanded in February 1945, Mike Calvert was transferred to Europe where he took over command of the famous Special Air Service (SAS) Brigade in March. Composed of five SAS battalions, including two staffed entirely by Free Frenchmen and one of Belgians, Calvert held command until the end of the war and like in the Chindits, was immensely popular.

(LEFT) Calvert consoles the widow of a French SAS officer who has been killed in action. (RIGHT) Calvert (in center with officer’s cap), inspects the Frenchmen of his command during an official ceremony at Tarbes in the south of France. The ceremony transferred the men from the British to the French Army. (B 15783) As he had with the Chindits, Calvert witnessed the disbandment of the SAS (in October 1945) as the largely conservative senior army leadership of the time saw little worth to special forces.

LIFE Magazine

At the “Aberdeen” fortress, U.S. Lt-Colonel Philip Cochrane of the 1st Air Commando (on left) discusses the evacuation of wounded men with British Officers.

(LEFT) In rare agreeable mood, Stilwell dashes up the steps to his headquarters to keep his appointment with the pretty journalist, Claire Boothe. Captain Frederick L. Eldridge smiles at the exuberance of his normally dour commander. (RIGHT) Two-day rations for the Chindits. It contains biscuits, dates, cheese, sugar, salt, chocolate, matches, tea, powdered milk and cigarettes. The pack seen standing is for parachute drop, and contains the equivalent of 10 days worth of the items displayed.

Weary and wounded Chindits wait by an improvised air strip for evacuation back to India. These men were part of a small raiding force which had attacked the Japanese south of Myitkyina. Two men stand on guard, not for protection but to watch a handful of Burmese collaborators and a Japanese soldier who have been captured (barely visible at the left of the picture).

Casualties from an attack on a Japanese roadblock the night before lie in a makeshift tent in enemy-held Burma. Although they have been evacuated from the frontline by light planes, another trip in larger Dakota transport planes to a regular hospital in India awaits them that night.

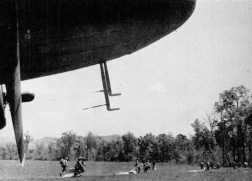

In these two 1943 photos, British load-masters push parachute cargo pallets out. While two men push, a third who tied himself to a brace, kicked the load out. Static lines tripped parachutes open (as is displayed in the photo on the right). According to the photographer, William Vandivert, one crew member almost fell out on this trip. (RIGHT) Signal fires guided the supply planes to the patch of gray-green jungle in the Burmese mountains east of the Irrawaddy. Although fighter protection was slim, on this occasion, the Dakotas had an escort of four Mohawk fighters, small match for Japanese Ki-43 Oscars.

In these 1943 photos, Major Walter Scott, in a strange quilted vest, shakes hands with the crew of a landed Dakota while his men hastily pull the plane’s loads of food and ammunition out of sight into the forest (shown in right photo).

(LEFT) A group of tired Chindits bring out a stretcher case towards the photographer, immediately behind whom is the light jungle airstrip. The man at left carries two Enfield rifles, the other being the wounded man’s. To his right, another Chindit of the 3rd West African Brigade, watches the jungle for Japanese raiders. The men, from First Platoon, 41 Column, 1st King’s own Royal Regiment have been identified as: (Front-from left, excluding the West African) — Denny Dennison, Mike Shere and Sgt. Guy. On the back left is Pvt. Stan Berry, a batman to Lt. J.D. Harrison who appears behind Sheere’s right shoulder. (KY 481781)

(RIGHT) In this photo of 1943 Chindits, a Dakota transports a group of 17 back to India, many of them wounded and ill with disease. The aircraft rigger hands a cup of water from a captured German jerrycan (of all things) to Corporal Jimmy Walker who was suffering from dysentery and an infected hip. In an interesting contrast to the differing features of Asians — on the left is a Gurkha sitting on a seat, while on the right is a Burmese.

(LEFT) Two Vultee L-1 Vigilant light planes at the “White City” airstrip which had been carved out of rough ground and jungle. Note how close the runway is to the rail line at the bottom of the photo. The Japanese repeatedly attempt to break through to this runway, only to be held back at the perimeter by the defenders. (RIGHT) In this 1943 photo, survivors from the first Chindit expedition celebrate at the hospital. Incidentally they are some of the same group of men photographed in the aircraft in the row above. On the far left is Sgt. Leslie Flowers from Manchester. The two men in the center with raised bottles are Sgts. McElroy and Tony Aubrey. Fed on two bottles of beer a day and two chickens apiece for lunch, the men are on their way to recovery.

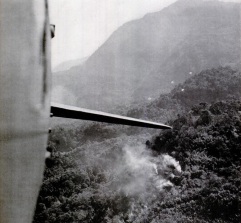

In this 1943 photo by LIFE photographer, William Vandivert, a British Dakota flies over enemy territory to airdrop supplies to Chindits deep behind enemy lines. Its crew is on high alert for enemy fighters, especially its dorsal gunners who vigilantly man their Lewis machine-guns.

(LEFT) Stilwell, in another one of his light moods, speaks with his American-born Chinese Aide, Lt. Richard Ming-Tom Young. This is Stilwell’s living room at his headquarters in Maymo. Note that a picture of the Alps hangs above the fireplace. On Stilwell’s epaulets are the three stars of a Lt-General. After the fall of Myitkyina, he would get a fourth star. (RIGHT) In this 1943 photo, a worn-out group of Chindits wait under the wing of the Dakota for an ambulance to take them to the hospital. These are the same men who were photographed while in the aircraft, three rows above. The bearded man in the center is Sgt. Tony Aubrey.

Two 1943 survivors: (LEFT) Showing the bullet that went through his back and came out of the hole in the belly, Pvt. Jim Suddery of Islington had a miraculous escape. Fortunately the bullet was of a small caliber. (RIGHT) Pvt. John Yates of Manchester. Despite his wounded hand, and suffering from a touch of fever and the usual jungle sores, he smiles broadly for the camera.

(LEFT) Chinese artillerymen from Stilwell’s American-Chinese Army fire their 75mm US-made Pack Howitzers down the Hukawng Valley Road. An American liaison officer watches them work.

(RIGHT) An American C-47 Dakota comes in low on 9 August 1943 to drop supplies without parachute to the Chinese. Many of the Chinese rank and file were pings, of the peasantry class, ill-treated by corrupt officers who sometimes denied them food and pay, and as a result they behaved as any class of destitute people frequently do — abominably, often stealing and looting supplies whenever the opportunity arose. Drops like these had to be carefully supervised by American officers. Anything less would result in whole swathes of supplies being stolen right under their noses. The drops were frequently made on ad-hoc jungle airstrips, numbered for quick identification with silk from parachutes.

In this 1943 photo, Chindits wave an enthusiastic farewell to the LIFE crew who are about to fly out in a light plane, knowing full well they themselves would only get to India by foot, still 170 miles away. When one of the men suggested a cheer, an officer said, “Cheer, but don’t make a sound,” because of the danger of nearby Japanese patrols.

The Imperial War Museum

(LEFT) The Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, inspects whites from a West African Brigade stationed at Bhopal in March 1944. (IND 2953) (RIGHT) The Viceroy of India, Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, knights Slim and three other generals on the field of Imphal in January 1945. Sir Robert Thompson, an ex-Chindit who later became internationally famous for defeating a Communist insurgency in Malaya in the 1960s, found this photograph haunting. ‘I see the ghost of Wingate present [every time I see this picture],” he said. “He was unquestionably one of the great men of the century,” who deserved his fair place among those honored. (CI 872)

Chindits wait insouciantly by their gliders to be flown out to “White City.” Other British and West African troops march behind them. Note the man marching in the immediate foreground – his rifle has a cup grenade launcher attached to the muzzle. (EA 20832)

(LEFT) A clean-shaven Wingate speaks with Cochrane. (RIGHT) A small detachment from the RAF’s 81 Squadron, together with a servicing party were based at “Broadway” in March. On the 13th, the Japanese discovered the airfield and attacked with 40 Ki-43 “Oscar” fighters. Getting airborne, the RAF pilots took on the enemy for 45 minutes, shooting down four planes and damaging several others. A brief respite followed, but on the 16th, more Japanese raiders appeared, only to lose one plane. Undeterred, another large group of Japanese fighters appeared on the following day. Only three Spitfires managed to get airborne. They shot down one raider before two of their own were killed, including the CO . The surviving pilot, Flying Officer Alan Peart, managed to get away to India, marking the end of the detachment’s service from the Chindit fortresses.

A Chindit Anti-aircraft crew watches a Dakota as it drops supplies in the perimeter of their fortress.

(LEFT) Men of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps (RIASC) usher along their mule train deep behind enemy lines. Aside from transport planes, mules constituted the next major transport element for Chindit columns in the jungle. (IND 1885) (RIGHT) Gurkhas cautiously edge forward through the Burmese undergrowth. (IND 3803)

Wingate, in typical unabashed style, tries out one of the mule pens on board a Dakota. On the right, he is shown moments later, straddling his Enfield SMLE No. 4 long-range rifle. These are some of the last photographs taken of him before his death. (EA 20828 & EA 20829)

(LEFT) Japanese troops probe a Chindit perimeter. (RIGHT) Lt-General Renya Mataguchi (without helmet), the stubborn commander of the Japanese 15th Army speaks with one of his men. Mataguchi’s testimony and that of other Japanese officers on Wingate’s efficacy, countered many of the negative things said about the Chindits after the war.

This group of tough hombres, from the HQ company of the 81st West African Division, pose for the photographer, their Enfield rifles held out. The most muscular among them seems to be the cook in the white apron, and any typical complaints of army food were probably not forthcoming. (SE 205)

Private Thomas Maycox of Salford, Lancashire, shaves in the jungle. Being on operations offered scant opportunity for proper hygiene and grooming, so moments were snagged when they could. Maycox belonged to a Mortar platoon as is evinced by the small 2-inch mortar lying in front of the foxhole, but his exact unit is unclear. (SE 3764)

(LEFT) A meeting of senior officers at Lalaghat – From left: US Brigadier-General William D. Old of the American Troop Carrier Command, General William “Uncle Bill” Slim, Wingate, Major Gaitley and Derek Tulloch. (MH 7881) (RIGHT) A Japanese-dominated bridge goes up in flames and smoke at Henu. (SE 7924)

Wingate waits at “Broadway” for C-47 Dakotas. To his left is U.S. Lt-Col. Clinton B. Gaty holding a signalling light and on the far right is Captain Baker. The popular Gaty commanded the Air Commando’s Light Plane Force but went on to lead the Air Commandos later that year. He never returned from a combat sortie against Japanese-held Meiktila on 26 February 1945. (MH7882)

Both combat types of the Air Commando captured on film at Hailakandi airfield – P-51A Mustangs overhead and a B-25 Mitchell medium bomber taxiing on the ground. (EA 20833)

Experimental Sikorsky Y-4 helicopters of the Air Commando during preliminary flights. The then-radically new machines went through their first combat deployment in the aid of Chindits. (IWM IND 3810)

“The Chindits” Booklet

These photo were published in a 1945 booklet written by Frank Owen for the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia. Layout was by Fred Oxtoby. It was printed by Don A. Lakin of The Stateman Press, Calcutta, India.

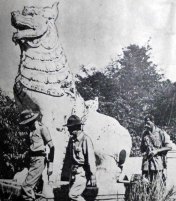

(LEFT) Chindits stroll past the physical embodiment of their insignia at newly-cleared Mawlu — the mythical Chinthe. (RIGHT) West Africans board a Dakota bound for White City. The timely arrival of the Africans would help win the battle there. (IND 7046)

(LEFT) West Africans hack an airstrip out of the jungle. (RIGHT) Men from Brigadier Lance Perowne’s 23rd Brigade prepare for a good bath after weeks of action against Japanese invaders in India.

A column of West Africans out on patrol, led by a white officer.

(LEFT) Using Lake Indawgyi near Hopin and the “Blackpool” fortress as an evacuation zone, the RAF flew in Sunderland flying boats to take out the wounded. (RIGHT) Gurkhas wait in ambush for the Japanese.

Hoofing it by air and sea: (LEFT) A mule is forcefully ejected from a transport plane onto Chindit-held Burma. Many of the mules had to be sedated for flight. (RIGHT) Other mules cross the 450 meter-wide (550 yards) Irrawaddy River.

(LEFT) An RAF liaison section in the field. Men like these were critical in keeping the air link open to the RAF and American 1st Air Commando Group. (RIGHT) Chindits safely back in India take the chance to rid themselves of their beards, cultivated in the field, partly to keep mosquitoes at bay and partly because there was little time or means for grooming on the battleground.

US 1st Air Commando Group (Other Photographs)

The notable pre-war child-star John Leslie “Jacki” Coogan, now an Air Commando glider pilot, fiddles with a gadget. No martinet, Coogan went in with the first wave on the night of 5 March 1944 — and survived. After the war, he famously starred as Uncle fester in The Addams Family. Before the war, Coogan’s earnings were stolen by his parents who openly declared that young Jackie “would not get a cent.” When later Coogan fell into financial difficulties, he was saved by Charlie Chaplin. (US National Archives)

(LEFT) In 1944, the Chindits would get their own private air force – the American 1st Air Commando Group, an equally dashing formation filled with unconventional types. One admiring British officer, Captain Griffin, would call the group an “extraordinary [flying] circus.” (US Air Force)

(RIGHT) An Air Commando fighter pilot, Lt. Jack Klarr, wears a jacket with the insignia of the group’s Fighter Element. Klarr’s first kill, a Japanese Ki-43 Oscar, occurred on May 19 during a patrol over “Blackpool.” By September the Chindits had been withdrawn and the Air Commando reorganized. Anti-airfield sweeps began on October 17 against a ring of airfields around Rangoon, and on the 20th, Klarr destroyed a Japanese aircraft on the ground at Hmawbi. More action soon followed. On December 13, while escorting twelve RAF Liberators on a bombing raid, his squadron encountered ten Oscars. Klarr gave the lead plane a burst from his guns. The Japanese fighter rolled and dived away, smoke trailing from its engine. Jack Klarr was awarded a “probably destroyed.” In 1945, he became a Captain and would go on to survive the war. (Elwood Jamison, 1st Air Commando Association)

(LEFT) The two co-commanders of the First Air Commando, Lt-Col. John Alison (in front row, without hat) and Phil Cochrane (on far right) at Hailakandi in March 1944. The other men, from left, are: Capt. Walter Radovich, Maj. Arvid “Ollie” Olsen and Lt-Col. Robert T. Smith who flew the B-25 in the background, Barbie III, named after his wife. Alison was a combat ace with seven aerial kills to his credit before he was assigned (along with his friend, Cochrane) to the ultra-secret Project 9, a unit which ultimately morphed into the 1st Air Commando. Alison passed away on 6 June 2011. He was 98. (U.S. Air Force Association) (RIGHT) Cochrane and Alison together in a wartime Associated Press color photo. (U.S. Air Force)

Sources:

For a full bibliography of all Chindit writing on this site, check the bottom of this post: Chindits – In 1944.