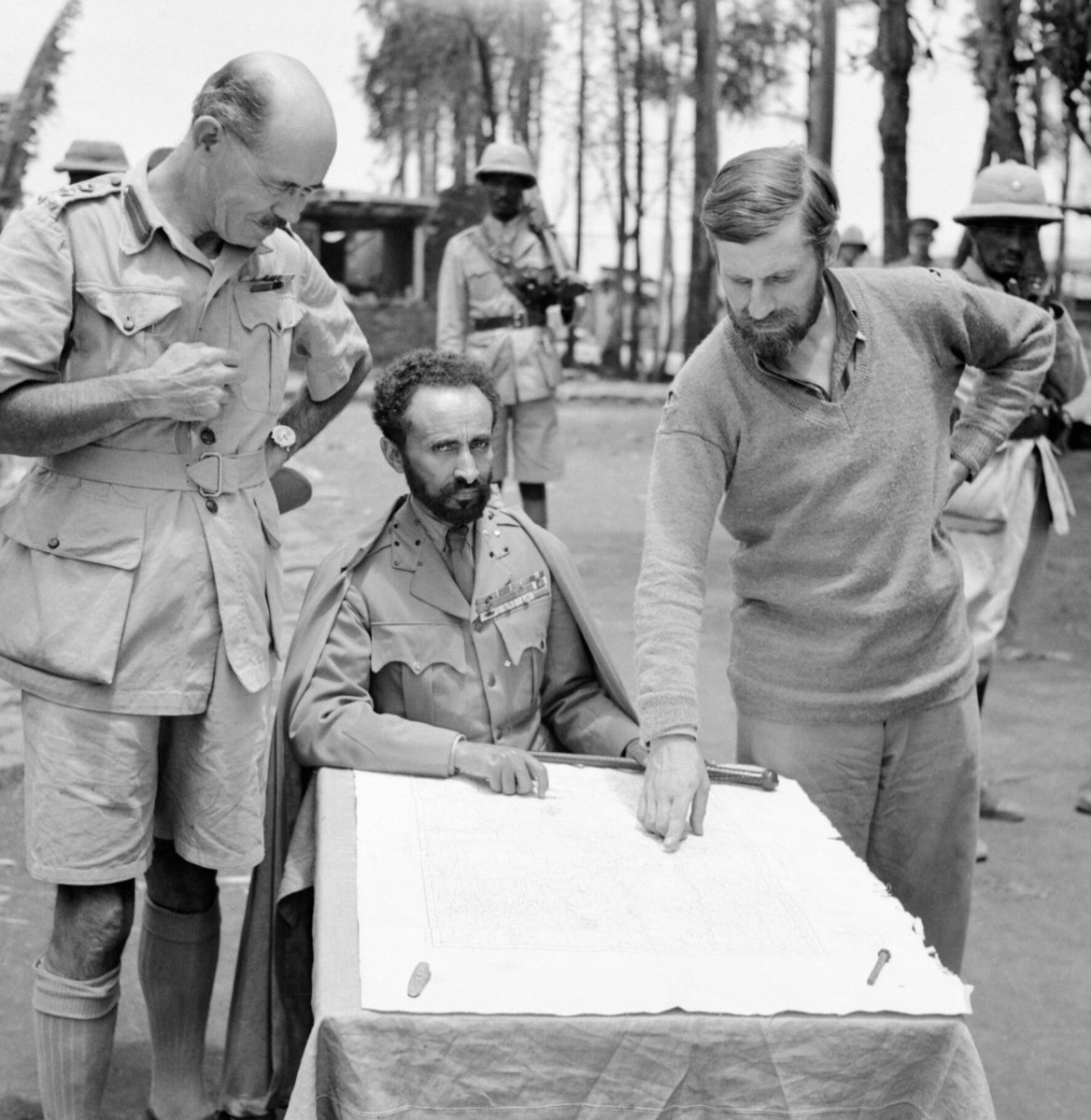

The Chindits were a product of wartime, a force hewn out of a desperate requirement for victory. By the start of 1942, the British colony of Burma was in maelstrom, under conquest from the Japanese whose rapid advance threatened India with invasion. The British desperately sought to hold the Japanese at bay. It was decided to bring in a Middle East expert to train the Chinese Army of Generalissimo Chang Kai-Shek for guerrilla warfare. That Middle East expert was Colonel Charles Orde Wingate — a junior colleague well known to General Archibald Wavell, commander-in-chief of India from 1941 — from his pre-war Palestine days and from wartime Ethiopia.

Following a long stopover in Cairo, Wingate arrived in India by Consolidated B-24 Liberator, meeting Wavell on March 19. By this time, the Burmese capital, Rangoon, had already fallen and Wavell conceived a new role for his subordinate: to carry out a guerrilla war against the Japanese using British army resources.

Operational ideas began to take shape. Wingate had thought deeply about the unconventional warfare and had came up with what he called “long-range penetration group” tactics, similar to the ones used by “Gideon Force,” an irregular combat unit he had set up and commanded in Ethiopia over a year earlier. He believed that a properly trained and supplied force could operate for some time behind enemy lines causing damage and disruption of the enemy’s communications, his supply lines and morale. He planned to have regular army units, properly trained for mobility that could engage in hit-and-run tactics without being constrained to conventional means of supplies or communications.

Mobility was vital for it would allow raiders to attack whenever they desired, wherever the enemy least expected it while allowing them to withdraw without being pursued. Units would infiltrate through the jungles and ridges in small groups, to operate deep in the Japanese rear, cutting supply lines and harassing local forces. Air power would assist with reconnaissance, supply drops and close air support, replacing the more traditional artillery in this role. Specially equipped RAF radio-controllers were to be attached to each of the groups.

After careful consideration, Wingate chose Burma’s central valley, where a vital railway network linked Mandalay with Myitkyina (pronounced Michenar) – the supply artery for Japanese forces in the north. Ignoring protocol and staff hierarchy, Wingate and his staff officers’ typed up their operational plan and submitted it directly to Wavell. With Wavell’s official backing confirmed, Wingate began improving the plan and by August 1942, a training center was set up for his yet to be formed force. This was not accomplished without difficulties. In the conservative Indian Army many high-ranked officers were opposed to the creation of a special force in their midst.

One opponent was Lt-General William Slim, commander of the British Fourteenth Army, who later wrote that Wingate, “fanatically pursued his own purpose without regard to any other consideration or purpose.”

Indeed, the bearded Wingate, suffering from eczema and frequently seen with an alarm clock dangling absurdly from the belt of his battledress, was seen more as a madman than a soldier. But on the search for his cadre, willing to think in unorthodox methods, he came across men who saw him as a genius. One was Major Michael Calvert, a member of the Bush Warfare School in Burma, before the country fell.

“With his thin face, intent eyes and straggly beard, [Wingate] looked like a man of destiny; and he believed he was just that,” Calvert wrote.

Others holding reservation about this new type of warfare, quickly fell to his engaging personality and willingness to experiment. Major Bernard Fergusson, an initial skeptic later said that, “Soon we had fallen under the spell of [Wingate’s] almost hypnotic talk; and by and by we – or some of us – had lost the power of distinguishing between the feasible and fantastic.”

Even as Wingate’s strategic thinking congealed, he was deftly promoted to the rank of Brigadier in early 1943 and given command of an entire brigade (officially, the “77th Indian Infantry Brigade”) with three full battalions. On paper, this was an impressive force. Reality was different.

The quality of troops were poor, Wingate determined. The Englishmen of the 13th Battalion, Kings Liverpool Regiment, were unenthusiastic for the role thrust upon them and they were considerably older than most soldiers, plus too well adjusted to garrison life. The next unit, the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles, was fresh but inexperienced, and comprised officers who were poorly trained and disliked their mission. The last unit – the 2nd Burma Rifles was in low-morale but comprised expert soldiers from the hill tribes of Burma, such as the Kachins, Karens and Chins, who became guides and reconnaissance troops.

In order to fill out the serious short-fall of experienced combat troops, Wingate assimilated the staff of the former Bush Warfare School which had by then been badly gutted, losing some 100 men to a Japanese ambush at the Irrawaddy River. Eleven survivors became the core of Wingate’s new force as did the veteran 142nd Commando Company, specialists of all types and men trained to handle pack animals.

Wingate christened his new unit, the “Chindits” after the Burmese word Chinthe, a mythical lion that guarded the Burmese stone temples.

The training slowly kicked in and began to build up the fitness, competence and confidence among the troops. Men were pushed beyond the limits of what they thought they could endure in the jungle and in the rain. L

Loading them with heavy packs, Wingate marched them through ruthless terrain until long marches and exhaustion became daily routine, with those passing out revived by instructors and forced to continue. Attending sick parade without a good cause became a punishable offense and orders were carried out on the run. Jungle craft was perfected to an expert level; this included teaching jungle navigation, patrolling, water discipline and marksmanship. Sickness, minor injuries and heat were deemed inconsequential by Wingate, who regarded the mind and willpower as keys to success.

The troops were made aware that they would soon find themselves operating without regular supply or medical aid deep behind enemy lines. Instructors ruthlessly weeded out those who were not physically or mentally fit for the mission, and Wingate constantly exalted the importance of winning the war, warning his troops that some would not be returning alive. Rather than lowering morale, this actually increased it, as the slovenly brigade became sinewed and ready for combat. The Chindits had been born.

More details

- The Chindits in 1943

- Chindit Units in 1944

- The Return of the Chindits in 1944, Part 1

- The Return of the Chindits in 1944, Part 2

- The Return of the Chindits in 1944, Part 3

- The Chindits in Photographs, Part 1

- The Chindits in Photographs, Part 2

Acronyms & Abbreviations

2IC – Second-in-Command

Bn – Battalion (In British Army, the basic combat unit capable of independent action)

CO – Commanding Officer

Coy – Company

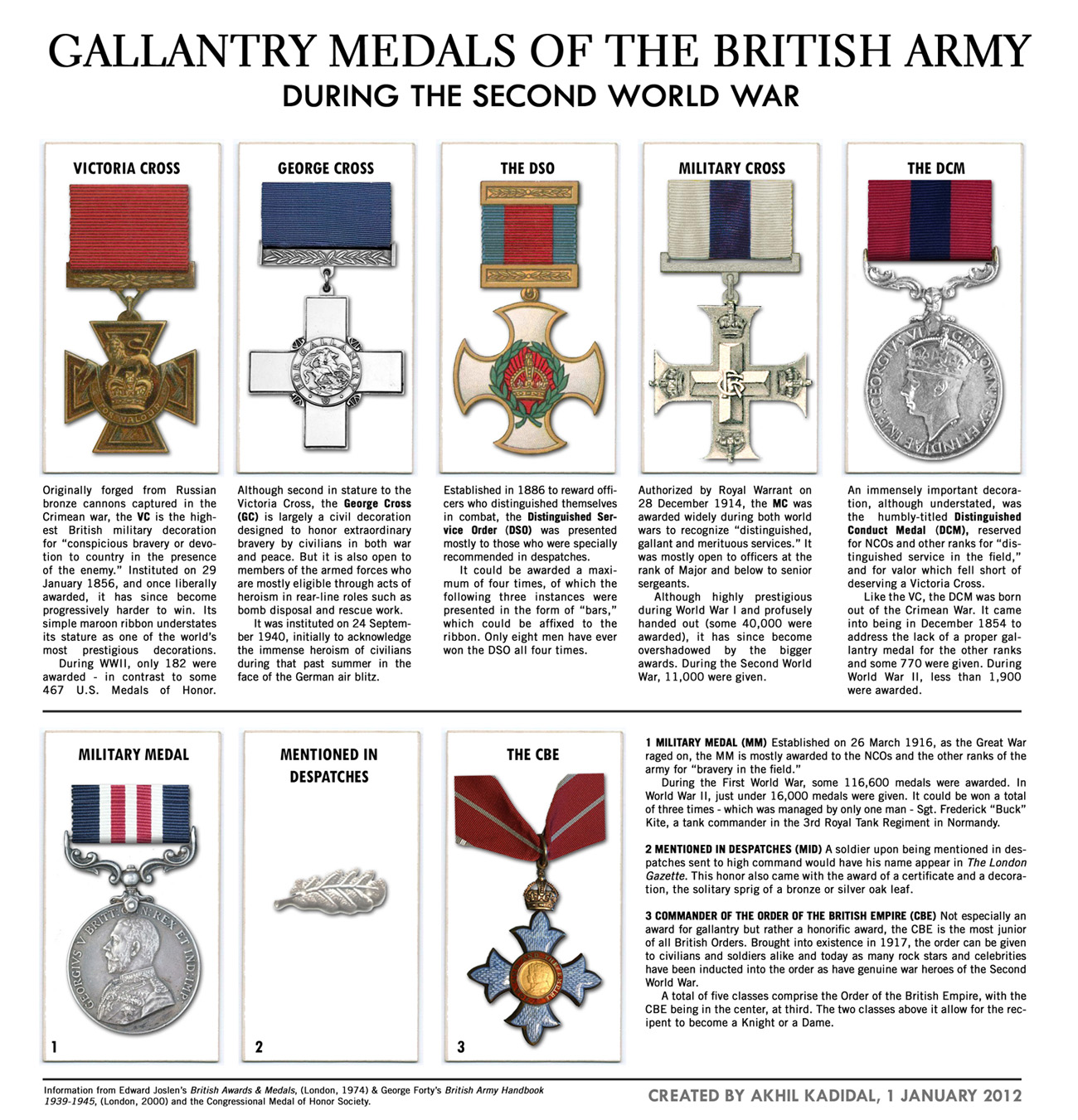

DSO – Distinguished Service Order (Decoration)

Evac – Evacuated from Burma. Relieved of command.

KIA – Killed in action

KIFA – Killed in Flying Accident

MC – Military Cross (Decoration)

RA – Royal Artillery

RAMC – Royal Army Medical Corps

RE – Royal Engineers

Repl – Replaced

Regt – Regiment (In the British Army, purely an administrative term)

RIAMC – Royal Indian Army Medical Corps

RIASC – Royal Indian Army Service Corps

WIA – Wounded in Action

How the Chindits were organized

The column was the main unit and all operations were column based (the term column was used literally because all personnel moved through the jungle in a single file). Each battalion had two columns, one commanded usually by the battalion commander and the other by his second in command. Each column had between 400-500 men.

Each column was composed of:

One company with four or five Rifle Platoons

One or two Heavy Weapons Platoons (each with two Vickers MMGs, two 3-Inch Mortars, one Flamethrower and two anti-tank Piats)

One Commando Platoon (with demolition and booby-trap experts)

One Recce Platoon (with a British officer commanding Burma Rifles-Karen and Kachin tribesman)

Plus assorted Royal Air Force controllers, sappers, signalmen and medical detachments.

Sources for all Chindit writing on this site

ALLEN, Louis, Burma — The Longest War, London: Phoenix Press, 1984.

ANGLIM, Simon, Orde Wingate and the British Army, 1922-1944, London: Chatto & Pickering, 2010.

ASTOR, Gerald, The Jungle War, Wiley, 2004.

BAINES, Frank, Chindit Affair, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2011.

BIDWELL, Shelford, The Chindit War: Stilwell, Wingate and the Campaign in Burma: 1944, NY: Macmillan, 1979.

BIERMAN, John & Colin Smith, Fire in the Night: Wingate of Burma, Ethiopia and Zion, NY: Random House, 1999.

CALLAHAN, Raymond, Burma 1942-1945, London: Davis-Poynter, 1978.

CALVERT, Michael, Prisoners of Hope, London: Leo Cooper, 1971.’——————–‘ Fighting Mad, Norfolk: Jarrolds, 1964.’——————–‘ The Chindits, NY: Ballantine, 1971.CHINNERY, Philip, Wingate’s Lost Brigade, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2010.

CLARKE, Peter, The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire, London: Penguin, 2007.DIAMOND, Jon, Stilwell and the Chindits, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2014.

‘————‘ Chindit vs Japanese Infantryman, London: Osprey, 2015.

FERGUSSON, Bernard, Beyond the Chindwin, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2009.

‘—————‘ The Wild Green Earth, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2015.KIRBY, S. Woodburn et al. , History of the Second World War: War Against Japan, London: HMSO, 1957MARSTEN, Daniel P., Phoenix from the Ashes – The Indian Army in the Burma Campaign, NY: Praeger, 2003.

MASTERS, John, The Road Past Mandalay, London: Cassell, 2012.

McLYNN, Frank, The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942-45, Yale University Press, 2011.MOREMAN, Tim, Chindit 1942-45, Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

MORTIMER, Gavin, Three Daring Dozen: 12 Special Forces Legends of World War II, London: Osprey, 2012.NESBIT, Roy Conyers, The Battle for Burma, London: Pen & Sword, 2009.OGBURN, Charlton, The Marauders, 1960OWEN, Frank, The Campaign in Burma, London: HMSO.ROMANUS, Charles and Riley Sunderland, Stilwell’s Command Problems, 1953.REDDING, Tony, The War in the Wilderness, The History Press, 2015.ROONEY, David, Mad Mike — A Life of Brigadier Michael Calvert, London: Pen & Sword, 2007.

STIBBE, Philip, Return from Rangoon, London: Pen & Sword, 1997.SYKES, Christopher, Orde Wingate, NY: World Publishing Company, 1959.

THOMAS, Andrew, Spitfire Aces of Burma and the Pacific, Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

THOMPSON, Julian, Forgotten Voices of Burma, London; Erbury Press, 2009.

THORBURN, Gordon, Jocks in the Jungle, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2012..TOWILL, Bill, A Chindit’s Chronicle, iUniverse, 2000.

TUCHMAN, Barbara, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, NY: Grove Press, 2001.

WAGNER, R.D. Van, Any Place, Any Time, Any Where, Altgen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1998.

WEBSTER, Thomas, The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theatre in World War II, NY: Harper Collins, 2004.

YOUNG, Edward, Air Commando Fighters of World War II, North Branch, MN: Specialty Press, 2000.

7th Leicestershire Regimental War Diary, The National Archives, WO 172/4900 (Unearthed by Hugh Vaugh)

Captain P. Griffin, IWM Museum of Records, PP/MCR/221 PG/1 ND (ca. 1970’s)

WEBSITES

1. Chindit Chasing, Operation Longcloth 1943 Website:

Interesting original research and a good collection of photographs collected by Steve Fogden pertaining to the 1943 expedition. Well worth a visit if you wish to know more of some of the men who participated in the 1943 campaign. Web address at: http://www.chinditslongcloth1943.com/index.html (Accessed 22 December 2011)

2. The Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment Good information on the Queen’s Regiment during the 1944 expedition. Look for Chapter 5. (Accessed 25 December 2011)

3. 2nd Yorks & Lancs War Diary, 1944 (Accessed 26 December 2011)

4. The British Military History Website: A good collection of information, orders of battle and other war research compiled by Robert Palmer, with an emphasis on the Burma campaign. (Accessed 4 January 2012)

5. The Chindits Society

The society was established in 2015 to connect the families of Chindits, researchers and historians with an interest in the Burma campaign. The aim of the society is to champion and project the history of the Chindits through “presentations and educational initiatives, assist families and other interested parties in seeking out the history of their Chindit relative or loved one, gather together and keep safe Chindit writings, memories and other materials for the benefit of future generations, ensure the continued well-being” of Chindit veterans and “promote fellowship between members.”

Web address at: http://thechinditsociety.org.uk/ (Accessed 2 April 2017)