THE CHOSEN

The chosen unit for the “token force” was the Free French 2nd Armored Division (the 2e DB) — untested as a unified combat force, and equipped and trained by the US Army. Formed from the 3,000-strong so-called “Leclerc Column” which had seen battle in North Africa, the division had since swelled to between 14,000 to 16,000 troops.

At its core were survivors of the 1940 debacle which had seen France folded into the Third Reich. Some, like Leclerc, were veterans of the hard battles of North Africa. However, a significant number of troops had not been traditionally trained for land combat. These included a regiment of sailors from the sunken Vichy Fleet who now manned M10 Wolverine tank destroyers.

The divisional commander was a thin, perhaps deceptively weak-looking French nobleman, Philippe Vicomte de Hautecloque, who had taken the nom de guerre of Leclerc to protect his wife and five children from reprisals.

With an ubiquitous cane, Leclerc presented the visage of a cultured country baron. But this mild exterior camouflaged his military pragmatism and force of will. He was also an iconoclast whose unconventionality would make him beloved to his men, if not France. Leclerc had made an oath the year before at Koufra in the Sahara that his division would not rest until the French tricolor flew from Strasbourg, France’s second capital.

The division itself had formed in 1943 in Tunisia with a cadre of battle-hardened veterans of the Saharan and Tunisian campaigns. But then, following orders from “above,” many of the black African soldiers, the Senegalese tirailleurs, who had fought for Leclerc with distinction, were told that they had no place in the division.

The BBC, in 2009, unearthed documents showing that this order originated from Eisenhower’s headquarters — specifically from Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, US Major General Walter Bedell “Beetle” Smith. In the memo, stamped “confidential,” Bedell Smith wrote that it is more desirable that the division “consist of white personnel.”

Bedell Smith indicated that the 2nd Division had been chosen for the role of liberating Paris because it was the only division in the Free French Army with “one fourth native personnel.” It is the “only French division operationally available that could be made one hundred percent white,” Bedell Smith added. (Mike Thompson, Paris Liberation made ‘Whites Only, April 2009, news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7984436.stm)

At the time, the US Army was a segregated military force with blacks serving either in logistical units or in separate combat forces.

The explanations for this prejudice were diverse: that Africans could not adapt to the cold of Europe and they could not master modern American equipment such as tanks.

New uniforms which had recently been provided to the tirailleurs were taken from them. Instead, outfitted with their old battle-stained uniforms, hundreds of battle-hardened men were sent back to their villages. (Mesquida, loc.1748-1755)

Leclerc was appalled. A series of debates ensued between Leclerc and his superiors. But the order was not reversed. Notwithstanding the cold, Tirailleurs did serve with the 1st Free French Infantry Division which saw action in Italy and eastern France from 1944 to 1945.

The manpower shortage created by the departure of the Africans prompted the division to seek inductees from indigenous and colonial Caucasian populations in North Africa. The division began to assimilate Europeans and Maghrebs from the Corps Franc d’Afrique, an ad hoc formation of political odd balls and refugees created by General Henri Giraud (a racist and de Gaulle’s rival for command of the Free French) during late November 1942. By mid April 1943, the Corps had 16,000 officers and 150,000 troops. (Marcel Vigneras, Rearming the French, 71) Among these were thousands of other Spanish volunteers, exiled from their homeland following the destruction of the second Spanish Republic in the civil war of 1936 to 1939.

Colonel Louis Dio, who commanded the division’s mechanized infantry force, the Régiment de marche du Tchad (RMT), informed Leclerc that many of the new foreign recruits were left-wingers with a significant proportion being anti-fascist Spaniards who had fled to French North Africa after the Spanish Civil War. Leclerc, who had once supported the Spanish Nationalist forces of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, was appalled. “A toff like me commanding a bunch of reds!” he said. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 434.7, Ch 7. 41%)

For Leclerc, a Catholic aristocrat descended from a family of Crusaders, the rise of the Spanish Republic with its opposition to the Spanish Catholic Church, was anathema. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 694.6, Ch. 7, 69% & Mesquida, loc. 607, 7%). Leclerc could not fathom that between 1931 and 1939 that the second Spanish republic was engaged in a battle, somewhat like the Church, for the salvation of the masses. Unlike the Church, however, which was interested in the maintenance of the status quo, the Second Republic stripped the Spanish nobility of their privileges, it gave women the right to vote, granted freedom of speech and a freedom of association to the masses. The Republic also attempted an ambitious land reform program to lift millions out of poverty.

Leclerc appeared not to realize that the real conflict between the Republic and the church was that the Republic was based on the separation of the Church and State, and its social reforms: civil marriage and legalization of divorce, would deprived the Church of some of its privileges. It would take months for Leclerc’s opinion about the “reds” under his command to change.

Meanwhile, the echoes of the Spanish Civil war seemed to run like an undercurrent through the division. Joseph Putz, the commander of the 3rd Battalion of the RMT, was also a veteran of the civil war. Putz had joined the French Army at 17 and had won honors during World War I. In 1936, joined the International Brigades when the civil war broke out in Spain and was soon a Corps commander on the Bilbao front. When France collapsed in 1940 to Nazi Germany, Putz joined the resistance movement in southern Morocco. He set up an infantry battalion in the Corps Francs d’Afrique which saw combat against the Axis in Bizerte in 1942. Hundreds of Spanish war veterans began gravitating towards his command.

Other recruits to the division were Moroccan Muslims, Christians, Corsicans filled with a hatred of Italian fascists, Jews determined to fight the Nazis, Pied Noir patriots and adventurers, indigenous Algerians who were keen to serve the homeland and even Tunisian Italians who had become anti-fascists.

Note: In his book, “Le Corps expéditionnaire français en Italie,” author Paul Gaujac mentioned that the 2e DB comprised 3,600 Maghrebs when the division was in Normandy and about 350 Spanish Republicans. The Free French divisions would undergo a dramatic change following the liberation of Paris. By September 1944, Free French forces comprised 550,000 troops: out of which 41% (or 225,000 men were white (comprising 195,000 Pied-Noirs, 25,000 metropolitans and 5,000 foreign Europeans). The remaining 59% (325,000 troops) were colonials: 233,000 Maghreb and 92,000 black Africans. (See Phillipe Buton, La France et les Français de la Libération). By May 1945, the Free French army comprised 1.3 million troops with the majority being caucasian.

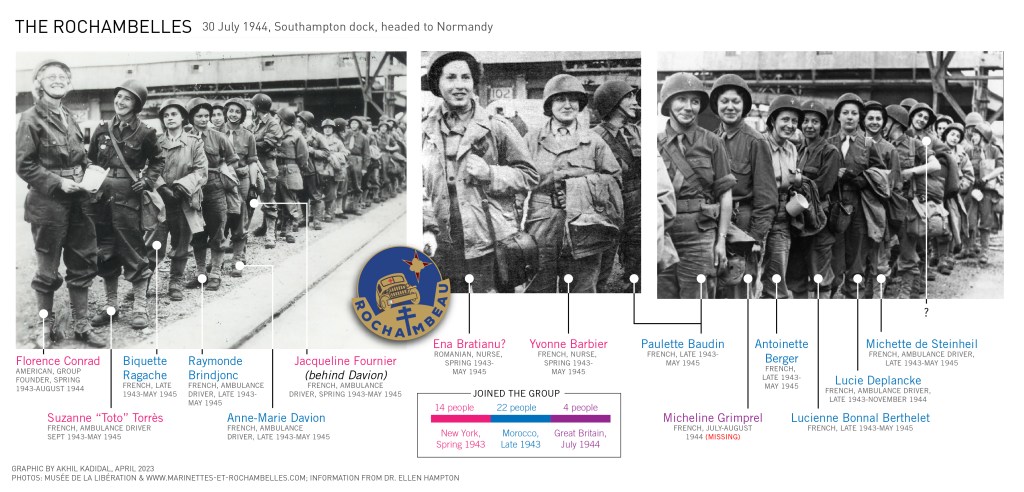

Other oddballs in the division included 30 British Quakers who joined the 3rd Company of the Division’s 13th Medical Battalion and an all-woman team of ambulance drivers and nurses. Organized by a wealthy American called Florence Conrad, this latter team of women were called the “Rochambeau” group – after Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau who had commanded French troops in the American revolutionary war.

As historian Ellen Hampton said, the name “Rochambeau” was intended to be recognizable to Americans. Conrad recruited 13 women in New York in 1943 (although four would leave in North Africa). Conrad also purchased 19 Dodge WC-54 ambulances. Another 22 French women were recruited in Morocco. The unit’s integration into the 2e DB was negotiated between Leclerc and Conrad in October 1943. In England, four more women joined the group. Eight-seven percent of the total group were French.

In Morocco, the women lived in a large camp amid US Army And Free French troops. The Free French began calling the group “Rochambelles” and the name stuck. The women were subject to rigorous drilling in Morocco. They were trained to drive the ambulances and to perform basic medical knowledge.

By January 1944, the division began trading its British equipment for US Army weaponry and kit. By April 1944, it had about “100% of its initial equipment and basic loads, plus a 30-day supply of tank replacements.” (Vigneras, Rearming the French, 171-172)

At the heart of the division’s strength were some 228 M4A2 and M4A3 Sherman tanks, 76 M3A3 and M5 Stuart light tanks, 45 M10 Wolverine tank-destroyers, over 250 M3 halftracks of various types, 126 artillery and anti-tank guns (including 81 Priest self-propelled artillery guns), over 2,000 trucks and nearly 400 jeeps or light cars.

The Leclerc Foundation has published a period graphic showing different figures for the types of vehicles in the division: 85 Stuart light tanks, 165 Sherman medium tanks, 36 M10 tank destroyers, 64 armored cars, 665 halftracks and various scout cars, 25 M8 Scotts, 54 Priest 105mm SP guns. (https://www.2edb-leclerc.fr/creation-de-la-2e-db-24-aout-1943/)

The division was organized around three battalion-size armored regiments. Each regiment had a headquarters squadron, a squadron of Stuart light tanks and three squadrons (or in the case of the 501e Régiment de Chars de Combat (501e RCC), three companies) of Sherman medium battle tanks. The 501e RCC was also the most pro-de Gaulle armored unit in the division.

Note: Remarkably, by June 1944, the entire Free French Army had only been issued with 368 M4A2 and 268 M4A4 medium tanks, and 273 M3A3 and 230 M5A1 Stuart light tanks. These 1,139 tanks also included replacement tanks and collectively were distributed among the three Free French armored divisions in existence, five infantry division reconnaissance battalions, and two non-divisional reconnaissance battalions. (Vigneras, Rearming the French, 245). So, the 2e DB alone accounted for 26.6% of these vehicles.

Each tank squadron/company had three platoons of five tanks each plus two command tanks. The RMT had a strength of 80 officers and 2,340 men. This appears to have included 170 African tirailleurs who had been allowed to stay on.

Although modeled around a US Army “light” armored division, the 2e DB differed in that it did not have a permanent regimental headquarters. Each battalion operated independently within Groupements Tactiques (‘GTs’ or Tactical Groups). A US Army liaison officer, Major Robert M Luminaski, was attached to the division. (Vigneras, 295)

On 7 April, Good Friday, De Gaulle announced to the division that it was being transferred from North Africa to England. By the end of the month, most of the division had arrived in Great Britain.

The division quickly found a language barrier between themselves and the British. This hindered the movement of arriving units from various ports to the divisional cantonment around Hull in Yorkshire. The medical Quakers were assigned as traffic police to help direct divisional units. By 6 May, 237 divisional tanks had reached the cantonment area. The final elements of the division arrived via two ships, the Capetown Castle and Franconia, in the last week of May 1944.

Among the last to depart Mers el Kebir were the Rochambelles and the RMT’s mascot, a young wild boar called “Jules” which had developed a taste for US Army chocolate mousse. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 483.4, 45%)

The departure of the Rochambelles was initially blocked by US officials citing military regulation prohibiting the transport of women on military transport. Leclerc had to personally intervene and tell the Americans that the Rochambelles were “not women, they are ambulance drivers.” (Ellen Hampton, Women of Valor, Ch. 2) The group was allowed to board the Capetown Castle which had 5,000 divisional personnel onboard.

Among them were several officers who would make a name for themselves in the war such as Colonel Louis Warabiot and Captain Jacques Branet of the 501e RCC, who had started to fancy one of the Rochambelles (Anne-Marie Davion). (Hampton, Ch. 2). The ship arrived at Liverpool in Great Britain on 30 May.

Leclerc’s HQ was at Dalton Hall near Beverley, on the estate of the 7th Baron Hotham. The Allied invasion of France (D-Day) took place on 6 June 1944 but the 2nd Free French had no role to play in the invasion.

The 2e DB was linked to Patton’s command upon arrival, but Patton himself was currently a non-combatant and officially only the head prop of an elaborate Allied ruse designed to keep the German 15th Army tied down in the Pa de Calais area. As the leader of the fictitious First United States Army Group (FUSAG), Patton officially commanded one fictitious army and two fabricated corps, and 16 non-existent divisions. That he was being asked to do this while his compatriots in the US First Army engaged in fierce combat in Normandy irked Patton. But “Blood and Guts” as he was somewhat disparagingly known by US GIs, was mollified by the fact that he was soon slated to go to Normandy at the head of the very-real US Third Army.

The 2e DB became an integral component of the US Third Army and its training, from May 1944. At training grounds at Fimber Station, the division was pushed to meet exacting US standards. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 480.1, Ch. 8, 45%). Fimber Station, a large area north of Hull also being used as a training ground by General Maczek’s 1st Polish Armored Division and the British Guards Armored Division. This gave the US Army an opportunity to gauge the performance of the Free French. It was initially found that the 2e DB underperformed in tank firing practice, compared to the 1st Free Polish Armored Division and the British Guards Division. (Mesquida, loc. 2095)

Furthermore when Patton inspected the 2e DB, he found what appeared to be schoolboys in the guard of honor. These were Corsican teenagers who had lied about their age to enlist.

“Are you planning on going to war with these choirboys?” Patton remarked dryly to Leclerc.

Patton was also taken aback by the sailors of the RBFM in their naval red pom-pom-infused Bachi caps, manning the M10 tank destroyers. He was also likely bemused by the fact that each Wolverine was named after a French battleship or a cruiser or even a type of wind. Patton insisted on seeing the Wolverine crews perform on the shooting line. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, Ch 8, 46%)

Aghast that the division may be delayed in playing its role in liberating Paris, Leclerc doubled the rate of training and the number of exercises. He also integrated his divisional officers with other units to bring back best practices. By 12 June, the 2e DB had passed the US Army’s technical inspection. (Mesquida, ibid.) But another 10 days of intensive training followed.

On 29 July, the division embarked on ships at Southampton and at Weymouth for the trip across the Channel. Embarking that same day was General Maczek’s 1st Free Polish Armored Division. Both units would meet in Normandy weeks later under trying circumstances.

In the morning, on 30 July, the ships sailed from port. It was 8 pm before the ships dropped anchor off the Norman coast. The Free French gazed at the dim French coastline. Leclerc gave voice to their feelings in his order of the day:

How do we describe our feelings when we put our feet back onto the soil of la patrie? This soil we left four years ago, leaving France under the boot of the enemy, with all that this has meant for each and every one of us. We return today as combatants, having continued the struggle for four years under General de Gaulle. We will see afresh the faces of our countrymen who will salute us enthusiastically from the midst of their ruins. We can only guess what they have suffered. My first duty is to salute those Frenchmen who have never despaired, who have assisted our allies, who have contributed to victory. I admire them and I honour them. For ourselves, we have reached our goal, we have come at last to help them, to relieve them and to continue at their sides in the great battle for liberation.

Alain Boissieu, Pour Combattre avec de Gaulle (1940–1945), 233

Another divisional soldier, Lt. Jacques Salbaing of the 5th Company of the RMT, wrote in his book, Ardeur et réflexion:

At dawn we arrived in sight of the coasts of France. Everyone was on deck, so as not to miss any of these moments which, we knew, were going to be historic for each of us, by the feelings they inspired in us. Everything was forgotten. We contented ourselves with admiring this majestic decor. The show was grand. The horizon was blocked, as far as the eye could see, on the left as on the right, by innumerable balloon-sausages attached to the ground, but from which hung cables, so as to constitute a gigantic net in which any plane would have been imprisoned. enemy trying to attack; Hundreds of boats were peacefully anchored. We were to learn some time later that we were in front of Utah Beach, facing the hamlet of Saint Germain de Varreville. As soon as the boat dropped anchor and came to a stop, we candidly prepared to touch down on French soil. But the day was absolutely calm, while the crew told us that it was sometimes necessary to wait several days before receiving the order to disembark.

https://www.2edb-leclerc.fr/utah-beach-saint-martin-de-varreville-manche/

By some accounts, the division took two to three days to disembark. The first divisional elements entered French soil on 31 July at the hamlet of La Madeleine. Shermans of the 501e RCC drove inland and paused near a farm.

The farmer asked them where in the United States they were from. In French, a regimental member, Corporal Emil Fray, told him they were French: “A whole division of us are coming ashore in the next few days.”

“You must be joking,” the farmer said, incredulously. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 565.3, Ch 9, 53%)

The bulk of the division started arriving in Normandy on 1 August en masse. Among the last to arrive on French soil was Captain de Corvette Raymond Maggiar’s RBFM and its tank destroyers. They only embarked at Southampton on 2 August. The divisional assembly area in Normandy was in the La Haye-du-Puits area (which the Americans knew as “La Hooey de Pooey”).

Meanwhile, that same evening, Leclerc had reunited with his cousin, François de Hauteclocque, mayor of Sainte-Suzanne-en-Bauptois, a small village about seven km east of La Haye. Then everything soured when Lerclerc’s brother-in-law by marriage, René de Tocqueville and his wife Marie who was a sister to Leclerc’s wife, Thérèse, arrived.

De Tocqueville started making excuses for Vichy. Marie echoed his opinions. Leclerc was irate. He had them shown out of his tent. (Notin, Jean-Christophe. Leclerc, 247-48)

On 6 August, the division set off for the war. That same night, it suffered its first casualties. German aircraft dropped bombs on the 501e RCC and the Rochambelles as they camped between the villages of Ducey and Saint-James, south of Avranches. In the resulting maelstrom, scores of men were casualties – as was a Rochambelle, the American Polly Wordsmith who had joined the group in Britain. Her legs were shattered and she evacuated to Britain. (Hampton, Ch. 3)

Another disaster struck on the 8th. Allied planes mistook the division for a German force and attacked near Saint-James. By 11.30 pm, GT ‘D’ and GT ‘V’ had suffered 20 dead and 200 wounded.

By 9 August, the division was headed towards Le Mans, having spanned 200 km, from Avranches to Le Mans in 48 hours. The division’s war officially began on 10 August when the 2e DB (with the US 5th Armored Division) advanced across the Le Mans-Alençon-Argentan front. The division pulled into the line, supporting the south flanks of the Allied trap at Falaise. In support were the US 79th and 90th Infantry Divisions.

Two more Rochambelles left their unit during this period – one because she was pregnant and the other who simply vanished off the face of the earth. This latter Rochambelle, Marie-Louise Charbonnel (aka Micheline Grimprel), a former resistance member, either quit the group or was possibly captured by the Germans on 16 August near Argentan, as the battle of the Falaise pocket grew in intensity. She was possibly later killed or died. A destroyed ambulance was later found in the area of her disappearance but not Charbonnel’s body. (See Hampton, Women of Valor)

Up to 20 August, the 2e DB fought a series of skirmishes and one major battle at Ecouche, southwest of Argentan. The unit was still some 90 miles southwest of Paris. De Gaulle pressed Eisenhower to explain why the division had not been sent towards Paris as had been agreed before D-Day.

Eisenhower was already furious to hear that fighting had erupted in Paris which threatened to affect the overall Allied plans to bypass the city. At the same time, he was embarrassed because he had not anticipated that an insurrection would erupt in the capital so soon. He informed de Gaulle that the current Allied plan called for Paris to be bypassed to avoid civilian deaths and damage to the city in costly street combat. In a sketch, he showed how the Allied forces would conduct a double envelopment of the city.

Eisenhower later wrote that he was “hopeful of deferring actual capture of the city unless [he] received evidence of starvation or distress among its citizens.” (Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, 355)

De Gaulle pointed out that if Eisenhower delayed a military advance into Paris “a disastrous political situation [might ensue], one would be disruptive to the Allied war effort.” (Collins & Lapierre, 144). Then, he played his trump card: The liberation of Paris is such a matter of national importance to the French that De Gaulle was prepared to extract the 2e DB from Allied command and dispatch it to the city on his own authority. (Ibid., 145)

Eisenhower had smiled at this, not believing that de Gaulle would go that far. This irked de Gaulle.

THE SOLO MISSION

Within hours, elements of the 2e DB were on the move, without authorization from their Corps Commander, US Major General Leonard Gerow of the US Army’s V Corps.

After midnight on 20/21 August, Leclerc dispatched Major Jacques de Guillebon with 17 light tanks, 10 armored cars and two platoons of infantry to Versailles (in all, about 150 men). The objective was to determine German strength in the area in lieu of a full-on advance by the 2e DB into Paris. In a letter to de Gaulle on the morning of 21 August, Leclerc explained his decision:

The command has had us marking time for the past eight days. They make sensible, judicious decisions, but, as a rule, four or five days later than they ought to have been made. The 2nd Division’s goal is Paris, they assure us. But in light of the current stalemate, I have taken the decision to dispatch Guillebon with a light detachment in the direction of Versailles, with orders to make contact, keep me briefed and to enter Paris should the enemy fall back. He moves out at noon and will be in Versailles by this evening or tomorrow morning. Unfortunately, I cannot do likewise with the rest of the division due to problems with fuel supply and lest I brazenly breach all the rules of military subordination. (Mesquida, loc.2240-2253, 46-47%)

Despite his claim to de Gaulle that the 2e DB was following military hierarchy, the division appeared to vanish from operational maps at the headquarters of US General Courtney Hodges’ US First Army (the 2e DB had been temporarily attached to this army). (See map for reference)

Colonel David Bruce, the top officer of American OSS in continental Europe who was with the writer Ernest Hemingway at Rambouillet, was astonished to discover that the precise location of the Leclerc Division had become a mystery. “Nobody had been able to tell us exactly where General Leclerc’s Second Armored French Division is located. Like the Scarlet Pimpernel, it is said to have been seen here, there and everywhere,” he said. (Lankford, Nelson, OSS Against the Reich, 167).

Captain Raymond Dronne, commander of the 9th Company of the RMT recalled that the 2e DB units which began to leave the Ecouché region on 23 August had been told to maintain radio silence to “as not to betray our advance”.

This “prevented us from maintaining our liaisons,” Dronne added. “Unable to open and read cards. We advanced, blind, dumb and deaf. I stopped in the middle of the night, in a soggy stubble. We were somewhere near Limours, we didn’t know exactly where. I had never seen such a mess. Vehicles from all units had gotten lost and followed columns that weren’t theirs. I spent the rest of the night sorting and regrouping my people.” (https://www.24-aout-1944.org/La-journee-du-24-Aout-1944/)

The US 12th Army Group’s daily situational map for 22 August shows the unit as being at Ecouche – the bloody battleground which the division had already decamped from days earlier. Within 24 hours, the division magically reappeared on maps at Rambouillet, 180 km east of Ecouche and only 38 km southwest of Paris.

This exacerbated Franco-American relations. Patton, in discussions with Gerow, wondered how much longer Leclerc would continue to follow US orders. Patton, however, had sympathy for the French cause. Less so did Gerow. (Neiberg, The Blood of Free Men, loc.308.8, Ch 6, 51%)

Meanwhile in Paris, Rol-Tanguy’s determination to restart the fighting was in part, contingent on fresh supplies of arms. He dispatched a subordinate, Commandant Roger Gallois, his Chief of Staff, to travel through Germans lines to reach the Allies. Gallois’ mission was clear: convince the US Army to resume arms drops over Paris.

Gallois breached the German lines at Pussay. About 500 yards away, he stumbled upon his first American GI. The reception he received upon being told that he was an emissary from Paris was indifference. For Gallois, who believed he was on a mission to prevent Paris from sharing the fate of Warsaw, the result was “emotional collapse.”

It was 1.30 am on 22 August when Gallois was finally brought before Patton. Old “Blood and Guts” had been sleeping. Now he arose and asked the Frenchman to tell his story.

“The Germans are demoralized,” Gallois reported. “Some of their defenses are very feeble. The Parisians are hungry but are nevertheless fighting to cut off the enemy’s retreat. They don’t understand the idea of a vast encircling movement by the Americans. They are already in a ‘cauldron’.”

Patton thought for a moment. “You should consider that the operations we are undertaking at the moment are not conceived lightly or without considerable planning and reflection. Our objective is Berlin, and we need to end the war as quickly as possible. The taking of Paris is not prescribed and we’re not going there,” he said. “We would have to be sure of feeding a large population and repairing various things destroyed by the Germans. We want to destroy enemy armies, not take towns!”

Patton’s tone became chastising. “You [the resistance] should have waited for orders from the Allied high command before beginning your insurrection on your own initiative,” he said. (Dansette, Histoire de la Libération de Paris, 240-241; Collins & Lapierre, 182)

Feeling thwarted, Gallois asked to speak to Leclerc. If ever there could be a sympathetic ear it was Leclerc’s. Instead, Gallois was dispatched to the headquarters of General Omar N Bradley’s US 12th Army Group outside Laval.

Congrats, how ever your articles are awesome. Your graphics are impressive!!! Greetings from South of Spain

Thank you. I appreciate your words!

AWESOME COVERAGE, FIRST EVER OF COMPLETE STORY BATTLE OF PARIS 1944, MERCI BEAUCOUP!!!!!!

Thanks, Eric. Appreciate the support.

No one word about Spanish Company “La Nueve” who was the first in go in to Paris and support resistance.

Read on. They are in there.

Hello Akhil, for these two photos:

“Dronne’s second-in-command of the 9th Company was Lt. Amado Grannell. He is seen here leading a patrol in Normandy. Curiously, he is armed with a German MP.40 submachinegun. (photo source unknown)“

We are not in Normandy, my caption: “Photo Krementchousky n° 1329 – Le Lt Amado Granell en patrouille, de Xaffévillers à Ménarmont (9ème compagnie du IIIème bataillon du RMT)” (Musée de la Libération de Paris – musée du général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin, Paris Musées)

“Lt-Colonel Jacques Massu, commander of the 2nd Battalion of the Régiment de marche du Tchad (RMT), rides as a passenger in a jeep executing a high speed turn through a Norman village – en-route to Paris. Although there has been some dispute that man in this photograph is not Massu, a close inspection of the facial features, the clothing and even the goggles, suggests that it is. (photo from “Du Tchad au Rhin,” Vol 3, L‘Armée Française dans la Guerre, 1945)“

We are in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, here is my caption: “Le commandant Jacques Massu – cdt du IIe bataillon du RMT – à bord de la Jeep “Moïdo” (413353) du II RMT de la 2e DB, conduite par Georges Hipp (FFL), à Pierrefitte-sur-Seine : venant de la redoute de la Butte-Pinson via l’avenue de la République, celle-ci tourne dans la rue de Paris/av. Général-Galliéni et se dirige vers Sarcelles”

Thanks, Guilhem. I have amended the captions. Good to get this information!

Dear Sir,

The photo:

“A German force, comprising two Panther tanks and several infantry attack the Prefecture of Police. Despite having 20,000 troops in Paris, the Germans were strung out. Their inability to mass infantry meant that von Choltitz could not overrun the prefecture. (photo source unknown)“

– which can notably be found at the IWM and at the Archives de la Somme – is not from 1944, but rather from 1947: they were filming a movie (see another photo Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images n° 1264105834). The Notre-Dame’s scaffolding was not there in 1944.

Cheers,

Guilhem Touratier

Hello Guilhem, thank you for this information. I really appreciate it and I have corrected the image caption. What is the name of this 1947 film? I would be interested in watching it.

Hello Akhil, you are welcome, it is with pleasure. Thank you for the correction. Unfortunately I do not know the name of this film…

Hello Akhil, thanks to a colleague, the film is that one: “Un flic”. Un flic (1947) – IMDb

Thanks, Guilhem. I will try to track down a copy of this film. I am astonished to learn that this is a crime/gangster movie.

Good afternoon Mr Kadidal,

concerning Lt-Colonel Massu I confirm that it is this man, those who say it is not him should go see their eye doctor. I have worked 20 years for my books on the liberation of Paris and have many photos of this officer and can tell you that it is him in his jeep.

Laurent FOURNIER

main author of “La 2e DB dans la libération de Paris et de sa région”

Thank you, Laurent. Good to hear from you again!