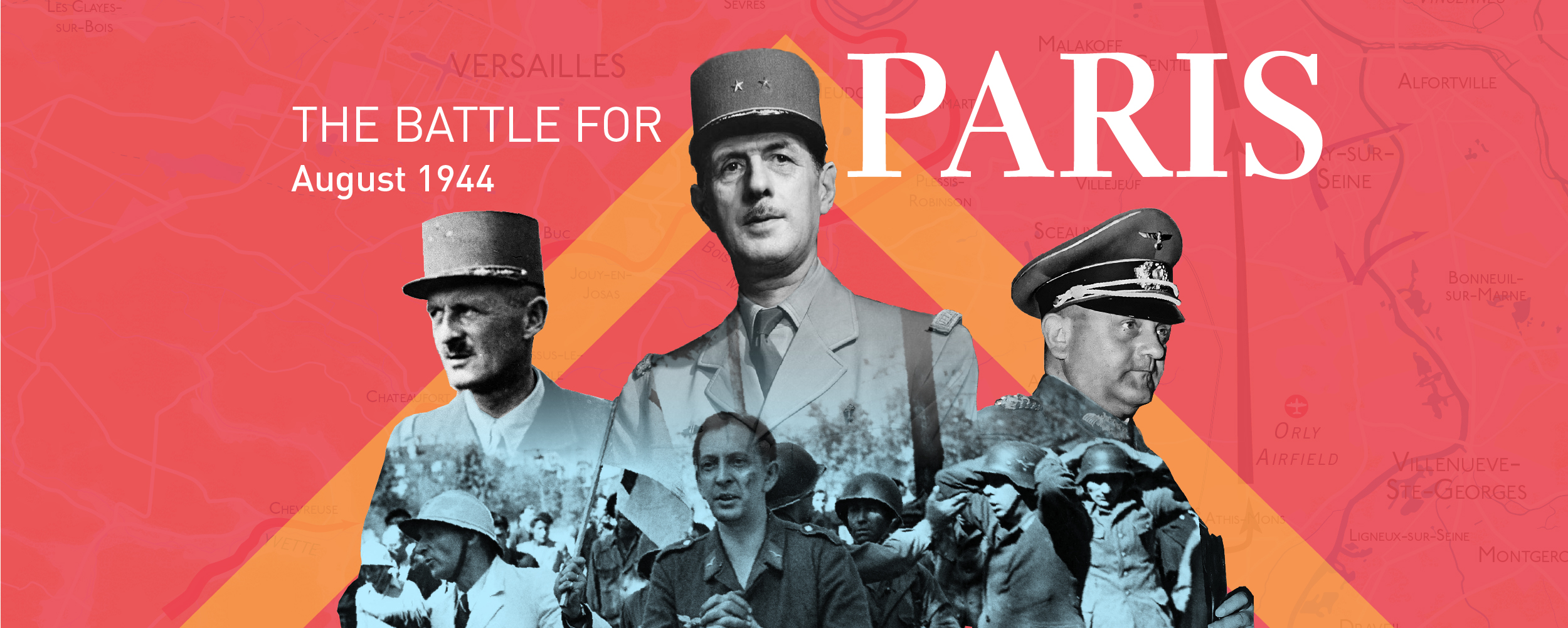

A premature armed uprising by the French resistance in Paris sets in motion a series of events, including a crazed order from Adolf Hitler to destroy the city. With no time to lose, Allied forces in Normandy act to liberate the capital.

Like prodigals returning home, a column of soldiers from a Free French armored division entered the Nazi-occupied city of Paris. It was the night of 24 August 1944. They were the first Allied combat forces in the capital in four years, but their numbers were paltry – only 172 men and three tanks. The column’s mission was paramount: to set up an advanced combat perimeter in the city.

This was intended to boost the morale of the population, which had become ensnared in a popular revolt against the Germans for five days. But the column commander, a thick-set, amiable French captain named Raymond Dronne, knew that the mission had more at stake. The detachment was expected to link up with the French resistance and help the rest of their division (the Free French Deuxième Division Blindée or 2nd Armored Division), to prevent what many feared would be Germany’s destruction of Paris.

The fear was not unfounded. The German dictator, Adolf Hitler, had ordered the German commander of the city, General Dietrich von Choltitz, to leave the capital a sea of ruins. The order was not unprecedented. The Germans had systematically obliterated other cities in Russia and in Europe. At that moment, at the other end of Europe, German forces were obliterating the Polish capital of Warsaw of its resistants, block by block, building by building.

It was 8.45 pm when Captain Dronne’s troops entered Paris through the undefended Porte d’Italie, one of the ancient gateways of the nearly 2,000-year-old city. Seeing the unfamiliar tanks and the strangely garbed men, the locals ran and hid. Then they saw the French tricolor on the sides of the vehicles and erupted into wild celebration.

Pushing past the jubilant crowds, the detachment headed towards the city hall, the ornately decorated Hôtel de Ville. The building was, for Dronne, a “symbol of Paris’ freedoms.”

News of the unit’s arrival at the Hôtel de Ville spread like wildfire throughout Paris, triggering a storm of emotions among the populace. Church bells began to ring. But the new liberators remained vigilant.

All around them were nearly 20,000 German troops, with their leader in Berlin determined to deconstruct a city which he had likened to the beating heart of France.

For four years, Paris had lain prostrate in the possession of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. It lay ensconced like a protected, gleaming jewel between the layers of three German armies: the Seventh Army in Normandy, the Fifteenth Army in the Pas de Calais area, and the elite Panzergruppe West, which had its headquarters east of the capital.

The arrival of the Allied armies on D-Day and the Battle of Normandy had prompted a stunning reversal of fortune for Nazi Germany. In nine weeks of warfare, the Allies shattered the German Seventh Army and Panzergruppe West (called the Fifth Panzer Army from 1 August). By 15 August 1944, most of Germany’s troops in Normandy had been cut off in the so-called Falaise Pocket.

Forty-eight hours later, the 30-square-mile pocket had snared 100,000 German troops from the remnants or elements of 27 German fighting divisions. They were hemmed in the north and northeast by Canadian and Free Polish forces. British forces pushed into the pocket from the northwest and the west, while American tanks and infantry of the US Third Army under Lt-General George S Patton held firm across the south.

Within the next three days, most of the Germans within the pocket were either dead, dying, wounded, or captured. Allied artillery and air attacks turned the pocket into a mush of blood, flesh, and molten steel.

An artillery battalion commander from the US 90th Division wrote in his diary: “The pocket surrounding the Germans is in the shape of a bowl and from the hills our observers have a perfect view of the valley below.… Every living thing or moving vehicle is under constant observation. I can understand why our forward observers have been hysterical. There is so much to shoot at”.

(Rick Atkinson, Guns at Last Light, loc. 16, Ch. 3, 17%)

The commander of the British 21st Army Group, General Bernard Montgomery, believed the pocket heralded the demise of the German Army on the Western Front. Yet, some 250,000 German troops and 250 tanks had escaped the pocket and were withdrawing east towards the Seine River. (Tucker-Jones, Falaise: The Flawed Victory, loc. 386.7, Ch. 16, 70%). The road to Paris, some 70 km northeast of the forward Allied lines, lay open.

German Confusion

Believing that the Allies could be in the city in days, the supreme German headquarters on the western front (Oberbefehlshaber West (OB West)) worked frantically to cobble together a defensive line south of Paris. Some German units, especially tank units, escaping from Normandy, were assimilated into fortified positions outside the city or deployed within the city itself.

On his own initiative, a bespectacled, egg-bald and anti-Nazi German general took on the task of organizing a defensive line around the western bank of the Seine. An estimated 25,000 troops were pushed into the line, interspersed with scattered armor, including dangerous Panther and Tiger tanks. But the defensive span, nicknamed the “Boineburg” line (after its progenitor), was replete with gaps.

With the looks of an affluent banker but badly wounded in a 1942 road accident, Lieutenant General Hans von Boineburg-Lengsfeld was the Commandant of Paris.

As a German moralist, Boineburg-Lengsfeld was determined to battle the Allies outside the city. Any fighting inside Paris, with its masses, its irreplaceable monuments, and its art treasures, he believed, was an act of irresponsibility. (Martin Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 592) As a German patriot, he had also vowed to depose Adolf Hitler from power. He had consequently become involved with members of the German officers’ corps in the 20 July bomb plot to assassinate Hitler. This would set in motion a series of events that would affect what happened in Paris.

The bomb that was to have killed Hitler at his Rastenburg headquarters in East Prussia exploded between 12.40 and 12.50 pm on 20 July (Der Anschlag, Spiegel, 20 July 2004).

At around 4 pm, believing the Führer dead, General Carl-Henrich von Stülpnagel, the military commander of occupied France, ordered Boineburg-Lengsfeld to arrest 1,200 senior SS officers in Paris – including the Chief SS Group Leader in the city, SS Gruppenführer (Lt General) Carl Oberg.

An hour later, Boineburg ordered the 1st Sicherungs (Security) Regiment, which was billetted at the sprawling École Militaire near the Eiffel Tower, to begin the roundup of the Nazi diehards. Anyone who resisted was to be shot. Generalmajor Walther Brehmer, commander of the Paris-based 325th Security Division, personally went to arrest Oberg at his home on No 57 Boulevard Lannes. With a pistol in his hands, Brehmer found Oberg in shirtsleeves and on the phone with Otto Abetz, the German ambassador to occupied France.

Before the war, Oberg was known as a decent family man. To his subordinates, he was a paradigm of his fairness. He was also a meticulous bureaucrat whose adherence to orders had turned him, in the words of Jacques Delarue, “a disciplined Nazi”. (Jacques Delarue, The Gestapo, loc. 468.7, Ch. 17, 63%)

Pierre-Charles Taittinger, president of the municipal council of Paris and patriarch of the Taittinger Champagne family, described Oberg as “a demonical creature capable of doing anything for his Fuehrer. A perfect incarnation of the brute beast, he seemed to have taken on the task of making himself detested – and in this respect he succeeded perfectly.” (Delarue, ibid)

Upon being confronted by Brehmer, Oberg leapt to his feet and demanded to know what was going on. Brehmer told him a fantastic lie: that the SS had launched a coup in Berlin. Flabbergasted and bewildered, Oberg gave himself up without a struggle. (Randall Hansen, “Invisible Coup,” http://www.historynet.com)

By 11 pm, nearly 1,200 SS, Gestapo, and SD personnel were in custody.

At 7.30 pm, a primary member of the bomb plot, General (retired) Ludwig Beck, the former Chief of the German Army Staff (until 1938), telephoned Stulpnagel from Berlin to confirm that all Gestapo, SS, and SD personnel in Paris had been arrested.

Stulpnagel confirmed the arrests. Many of the “Parisian” Nazis were held at the sprawling prison at Fresnes, south of Paris, or at Fort de l’Est in Saint-Denis. Senior Nazis, including Oberg, were held at the Hôtel Continental, across the street from the Hôtel Meurice. The anti-Hitler German generals planned to shoot these men the following morning at the École Militaire.

The anti-Hitler conspirators had powerful support from Field Marshal Günther Adolf Ferdinand von Kluge, the commander of OB West. But then, at about 8 pm, von Kluge learned that Hitler had survived the bomb and began to betray the conspirators. (Delarue, loc. 645.8, Ch. 21, 87%)

That Hitler had survived the blast sealed the fates of von Stülpnagel and thousands of other co-conspirators – Except Boineburg-Lengsfeld, whose role in the plot would go undiscovered for over half a year. Brehmer also survived the putsch by arguing that he was simply following orders. Both men went into the OKH Führerreserve (Leaders’ Reserve).

Boineberg was finally suspended from his functions as military governor of Paris on 3 August for refusing to destroy the bridges over the Seine. His replacement was General Dietrich von Choltitz, an aristocratic Prussian who had a reputation as a “destroyer of cities.” (Mallett, Hitler’s Generals in America, University Press of Kentucky, 2013, 37).

In May 1940, Cholitz had ordered the devastating bombing attack that destroyed Rotterdam. In July 1942, he became a general after ravaging Sevastopol – but at the cost of an arm wound and 4,453 casualties out of 4,800 men in his regiment. (Martin Blumenson, Liberation, 130-131)

Note: Brehmer was in the Führerreserve until 22 December 1945 and Boineburg-Lengsfeld until 20 February 1945. This reserve was dominated by military incompetents or politically problematic officers.

Cholitiz was selected to take charge in Paris on the personal recommendation of General Wilhelm Burgdorf, the chief of personnel of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW). Burgdorf described von Choltitz as “an officer who had never questioned an order, no matter how harsh it was.” (Mallett, 36) However, other senior officers had a far different opinion of him. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, German commander-in-chief in France, assessed Choltitz as being “decent but stupid.” (Tucker-Jones, loc.132.4, Ch. 4, 24%)

Choltitz himself was rueful about his reputation. “It is always my lot to defend the rear of the German army. And each time it happens, I am ordered to destroy each city as I leave it,” he said. (Blumenson, Liberation, 131) But in the years since Rotterdam and Sevastopol, von Choltitz had become convinced that Hitler was insane.

This impression was formed when von Cholititz met Hitler shortly after the 20 July bombing to receive his orders. Perspiration dotted Hitler’s face. Saliva ran from his mouth. The desk on which Hitler leaned, reverberated as Hitler reverberated, von Choltitz later wrote.

“Herr General,” Hitler told von Choltitz, “dozens of generals — yes, dozens — have bounced at the end of a rope because they wanted to prevent me, Adolf Hitler, from continuing my work.”

Continuing, Hitler told Choltitz that he was being sent to Paris and that the city “must be utterly destroyed. On the departure of the Wehrmacht, nothing must be left standing, no church, no artistic monument.”

Continuing, Hitler told Choltitz that he was being sent to Paris and that the city “must be utterly destroyed. On the departure of the Wehrmacht, nothing must be left standing, no church, no artistic monument.”

In Allied captivity, von Choltitz was surreptitiously recorded telling his fellow captive Generals that Hitler had harangued him for “three-quarters of an hour” – while standing. (Neitzel, Tapping Hitler’s Generals, 133)

“I was convinced…the man opposite me was mad!” von Choltitz wrote years later. (Blumenson, Liberation, 131)

Choltitz’s initial mission was to make Paris “the terror of all who are not honest helpers and servants of the front.” (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 592). He took up his new role on 14 August. He could not have guessed then that General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander of the European Theater of Operations (ETO), had little interest in seizing Paris through a direct assault.

A report prepared by SHAEF’s three-man planning team warned of “prolonged and heavy” street fighting if the Germans occupied Paris in strength. The report, titled Neptune Operations II – Crossing of the Seine and Capture of Paris, warned that any fighting could potentially end in the “destruction of the French capital.” (Collins & Lapierre, 12-13)

This fear had prompted the French Army to evacuate the city in 1940 to avoid turning it into a battleground. (New York Times Complete World War II: The Coverage of the Entire Conflict, Reich Tanks Clank in Champs-Elysees, 15 June 1940, 109).

Eisenhower was also concerned that the cost of feeding and sustaining the Parisian population would rob the Allies of their momentum towards Germany. “The capture of Paris will entail a civil affairs commitment equal to maintaining eight divisions in operation,” the SHAEF report said. (Collins & Lapierre, 12-13).

A US 12th Army Group report added in August that, “serious problems will exist with respect to the feeding of the civilian population on the capture of Paris.” (Coles & Weinberg, Civil Affairs, 738-739.) The report stressed that the estimated population of the Paris area was likely 3,800,000. The French government in exile in London estimated that number at 5,000,000.

In the four years of the privation imposed by the Nazi occupation, historians Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre wrote that the city had become the “largest country village” in the world, a city which awoke to the cries of thousands of roosters from “backyards, rooftop pens, garrets, spare bedrooms, even broom closets.” It was a city where the population risked their lives daily to cut “forbidden blades of grass” in parks to feed rabbits kept in bathtubs. Paris was also a city that had adopted a vegetable normally fed to cattle as a daily staple of human consumption – the rutabaga. (Collins & Lapierre, 8-9)

The 12th Army Group estimated that the “supply of food available in Paris at the moment of liberation will not last for more than 48 hours” and that the probable “disruption resulting from military operations will prevent the normal flow to Paris of any substantial amounts of food during the first 10 days.” (Coles & Weinberg, Civil Affairs, 738-739)

The 12th Army Group estimated that 2,400 tons of supplies would be required per day to maintain the prevailing ration scale during the first 10 days. “It is estimated that an average of 1,000 tons per day will be required during the secondary phase of 35 days,” the 12th AG report added. (Coles & Weinberg, Civil Affairs, 739)

Eisenhower issued “firm instructions” to the Free French General, Pierre Koenig, a hero of the North African campaign and now head of the French resistance (the Forces françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI)), that “no armed movements were to go off in Paris” until he had given the order.

But events were moving beyond Eisenhower’s control. Paris, for the French, was not the whole of France, but its heart, as a NYT reporter, John MacCormac, wrote on 18 August 1944. (NYT Complete WWII, 461) Paris in history was where revolutions and wars began and stopped. No one was more acutely aware of this fact than General Charles de Gaulle, head of the Free French government in exile and the Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Française (Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF)).

For days, de Gaulle had worried about Paris. He was convinced that if the Allies did not take Paris through military force, it would become a stronghold of the French Communist Party. To deprive the communists of political and military power, de Gaulle had even ended all arms drops into the Paris region from 14 June. Despite this, de Gaulle estimated that the communists already had some 25,000 armed men in the city. (Collins & Lapierre, 17).

De Gaulle’s representative in Paris, Alexandre Parodi, would later say that de Gaulle expected nothing less than “an armed communist challenge to his authority.” (Collins & Lapierre, 17). The French resistance in Paris was under the firm control of the Communist Party. And even before the embers of carnage in the Falaise pocket had vanished, unrest had erupted throughout Paris — initiated by the communist-dominated branches of the French resistance.

The Paris branch of FFI was led by a charismatic communist and anti-fascist, Henri Tanguy, a 36-year-old veteran of the International Brigades of the Spanish Civil War who had reinvented himself as a resistance leader with the nom de guerre of “Colonel Rol” — in homage to a friend slain in Spain. The FFI had a clear goal — liberate the capital from Germany using civil unrest and insurrection.

By mid-August, Tanguy had devised the plan to launch a strike of railway workers at the Villeneuve-Saint Georges marshaling yards. This was to be the first of a series of strikes to cripple the city and catalyze a broader, popular insurrection. That a popular uprising would claim hundreds of lives and leave Paris gutted was part of the calculations.

By 18 August, more than half the railway workers were on strike. Then, the French police began to vanish from the streets as a response to being disarmed by Choltitz. A resistance group within the Paris police had called for a strike on 15 August.

The Uprising Begins

On 19 August, a damp Saturday, the popular insurrection spilled out into the streets. Amédée Bussière, a loyal Vichy and the Police Prefect, awoke at the Prefecture of Police to the sounds of a crowd outside his window. If Bussiere had hoped that the noise was his men returning to duty, he was mistaken. Below stood Yves Bayet, the head of the Gaullist faction of the Police. To Bussière’s disgust, Bayet was out of uniform and wearing a checked suit.

Bussière’s eyes widened when he heard Bayet declare that he was taking “possession of the Prefecture of Police… In the name of the Republic and Charles de Gaulle.” (Blumenson, Liberation, 131-32)

The night before, French policemen in the resistance had met in Montreuil and had agreed to occupy the Préfecture of Police — a stately building across from the cathedral of Notre-Dame. By mid-morning, the prefecture was in the hands of distant de Gaulle — an event that not even the communist faction of the FFI had been privy to.

Bussiere’s next act of shock was to discover that he had been arrested. (The Liberation of Paris, https://liberation-de-paris.gilles-primout.fr/tous-a-lhotel-de-ville) His replacement was Charles Luizet, who had parachuted into Southern France from Corsica a week before, on de Gaulle’s orders. Luizet had arrived in Paris two days before. (Collins & Lapierre, 106-107)

Some 2,000 gendarmes and civilian resistants loyal to de Gaulle barricaded the prefecture’s entryways, set up rifles and machine guns along parapets and windows, and stockpiled Molotov cocktails made by Madame Curie’s son-in-law, Frédéric Joliot-Curie. (Nicholas Rankin, Ian Fleming’s Commandos, loc.4371.1, Ch 12, 63%)

By 10 am, the French tricolor, not seen openly in France for four years, began to sprout across the city.

Caught off-guard by the Gaullist uprising, which had preempted the communist-led uprising, Tanguy quickly issued orders for the FFI to occupy key buildings, including Paris’ central city hall, the Hôtel de Ville.

The battle of Paris was emerging as not just a war of opposing military forces, but also a battle for ideology and political power. The communist party controlled two out of the three resistance political committees in Paris — the Comité Parisien de Libération (CPL) and the Comité d’Action Militaire (COMAC). The communists were also a powerful minority in the last committee, the Comité National de la Résistance (CNR), which de Gaulle had founded in 1943 but had since come to be regarded as a toothless force compared to CPL. (Collins & Lapierre, 19)

The communist armed militia, the Francs-tireurs et partisans (FTP), was also a potent force.

For days, the Germans had been disconcerted by the growing and open French defiance of their authority in the capital. But von Choltitz still commanded sizable forces: between 25,000 and 30,000 troops (primarily from the 325th Sicherungs Division but also over 3,000 fanatical SS troops). Choltitz also had some 80 tanks (including 20 potent Panther and Tiger tanks – many from the elite Panzer Lehr and 9th Panzer Divisions which had escaped Falaise.

The Germans also possessed 23 artillery pieces (ranging from 105 to 150 mm), 35 anti-tank guns (from 75 to 88mm caliber), and six other guns.

The French resistance had been effective as an army of shadows, conducting sabotage, collecting intelligence, harassing isolated German forces, and burning gasoline depots. But as a conventional combatant army, they were out of their depth.

By 3.20 pm, the Prefecture was under attack by the Germans. A Tiger tank clanked around the building, shelling the structure. A minor fire erupted in the north wing of the Préfecture. The Tiger then took up position on the main gate on the east side of the Prefecture, across from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. Two 88mm shells from the tank tore through the front gate, wounding two men. But astonishingly, the Tiger then withdrew. The Germans did not have enough infantry to quash the prefecture’s resistance. (Cobb, Eleven Days in August, 149-150) Choltitz was hard-pressed to spread out his infantry across the city to prevent the insurrection from spreading.

A temporary hospital was set up at the Hôtel-Dieu, across the road from the Préfecture, as resistance casualties began to mount.

Choltitz was even presented with an opportunity to bomb Paris into submission. A day before, a Major from Generaloberst Otto Dessloch’s staff had visited the general to suggest that Luftwaffe bombers based at Le Bourget airfield north of the capital could be used to “suppress the troubles in Paris.” (Collins & Lapierre, 167) Dessloch had replaced Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle as commander of the German Air Force’s Luftflotte 3 on 18 August.

Choltitz was intrigued by the idea of using the bombers to blast the Prefecture of Paris, but then hesitated when the Major suggested using the bombers to raze the northeastern corner of the capital (from Montmartre to Pantin), in an indiscriminate night raid. (Collins & Lapierre, ibid).

The French resistance believed that the Germans had between 100 and 120 bombers at Le Bourget. (Cobb, footnotes, 368) However, the Luftwaffe had only gruppe of bombers at the airbase (II/KG53) which had an establishment strength of 26 aircraft, plus several transport, communications, aircraft control, and meteorological units. (Henry L deZeng IV, Luftwaffe Airfields in France 1939-45, 2014, privately published, www.ww2.dk/, Accessed 26 January 2023)

Furthermore, the bombers’ window of opportunity was rapidly closing. By the 19th, the Luftwaffe had begun to evacuate from Le Bourget. The Allies had bombed the airbase two days before.

De Gaulle Attempts a Ceasfire

Concerned that the fighting in Paris was getting out of hand, De Gaulle instructed his CNR and GPRF subordinates to attempt a ceasefire in the city. Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul general, volunteered to negotiate with von Choltitz. Nordling learned on the evening of the 19th that Choltitz was willing to discuss the conditions of a truce with the Resistance.

A shaky armistice was ushered in at 8.30 pm on 19 August — to the fury of Rol-Tanguy and other FFI resistants, who saw the truce as a subversion of their own military objectives to secure the city before the arrival of the Free French.

In a meeting, a fiery Rol-Tanguy denounced the truce with the Germans as an agreement with murderers. Jacques Chaban-Delmas of the Comité français de Libération nationale (CFLN), only 29 years old, but already a Brigade-General in the Free French army (albeit without any troops; his role was that of a liaison officer), retorted that the communist resistance wanted to “massacre 150,000 people for nothing!”

This prompted Pierre Villon, co-leader of CNR’s Committee of Military Action (COMAC), to cry out that he had “never seen such a gutless French general.” Villon vowed that if the truce were restored, the Communists would “plaster every wall in Paris with a poster accusing the Gaullists of stabbing the people of Paris in the back.”

This deflated Parodi. “My God,” he exclaimed. “They’re going to destroy Paris now. Our beautiful Notre-Dame will be bombed to ruins.”

“So what if Paris is destroyed?” Villon said. “We will be destroyed along with it. Better Paris be destroyed like Warsaw than that she lives another 1940.” (Blumenson, Liberation, 135)

According to Collins and Lapierre, the Chaban-Delmas warned Rol that the price of an insurrection would be 200,000 dead. To this, Tanguy allegedly replied: “Paris is worth 200,000 dead.”

(Collins & Lapierre, 40; Rol-Tanguy “vigorously” denied making this statement, Cobb, footnotes, 368).

In part, the communist agenda was driven by a desire to prevent France from returning to the country it was before 1939 – a country which the far-left saw as being ruled by the class of privilege.

The resistance newspaper, Combat, editorialized this position on 21 August by writing that France must not return to the France of 1939, because the prewar “ruling class had failed in all its duties.” The way forward for the country now was “a true people’s and workers’ democracy…. Having begun with resistance, [we] want to end with Revolution,” the paper said.

In an editorial on the following day, the writer Albert Camus asked people to keep in their minds the image of “dead children, kicked and beaten into their own coffins,” as they thought of the better, more egalitarian France they wanted to create. “We are not men of hate,” he concluded, “but we must be men of justice.” (Jacqueline Lévi-Valensi, ed., Camus at Combat: Writing 1944–1947, 12-13).

By nightfall on the 19th, the resistance had been bloodied, but so too had the Germans. Choltitz reported that his forces had suffered 50 killed and 100 wounded. (Blumenson, Liberation, 132)

Then, on the 20th, Rol-Tanguy’s units launched their insurrection. As the Germans’ hold on law and order collapsed, bands of armed FFI fighters began to move openly in the streets.

At around 6 am, Roland Pré, a civil delegate of the GPRF, and Léo Hamon, vice-president of the Paris Liberation Committee (CPL), appeared at the Hôtel de Ville with a detachment of police. Stunned, the guards of the city hall let the resistance pass inside. Hamon took possession of the building in the name of the Provisional Government of the French Republic.

The prefect of the building, René Bouffet, was arrested. The day before, Bouffet, perhaps hoping to save himself, had assured Raymond Massiet (alias Dufresne), Chief of Staff of the FFI’s Seine faction (commanded by the Gaullist Colonel de Marguerittes Lize), that the doors of the Hôtel de Ville would be open without resistance.

A well-known LGBT writer and poet, Roger Worms (aka Stéphane), was appointed military commander of the building. However, Worms had no combat experience, and he was subsequently superseded by Aimé Lepercq (aka Landry), president of the FFI’s l’OCM (Organisation civile et militaire).

A former regular army soldier and the previous commander of the FFI in Paris until his arrest by the Gestapo on 8 March, Lepercq had been incarcerated at the massive prison at Fresnes, south of the capital. To his luck, a shoddy German investigation into his background turned up nothing. He was released on 17 August. (http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org)

But Lepercq would only arrive in Paris on 23 August. Meanwhile, Marcel Flouret, who had been appointed the new prefect of the Hôtel de Ville, arrived on the afternoon of the 20th. He was welcomed by Captain Stéphane. The FFI sent out armed parties to hold buildings on the Rue de Rivoli, Rue de la Verrerie, and Rue du Renard to prevent German troops from approaching the Hôtel de Ville.

Hitler seeks Destruction

In Germany, Hitler was still clamoring for the systematic destruction of the city. On 20 August, he issued his famous “field of ruins” order:

The defense of the Paris bridgehead is of decisive military and political importance. Its loss dislodges the entire coastal front north of the Seine and removes the base for the V-weapons attacks against England. In history, the loss of Paris always means the loss of France. Therefore, the Führer repeats his order to hold the defense zone in advance [west] of the city… Within the city, every sign of incipient revolt must be countered by the sharpest means… [including] public execution of ringleaders… The Seine bridges will be prepared for demolition. Paris must not fall into the hands of the enemy except as a field of ruins.

(Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 598)

A day before, Hitler ordered reinforcements be sent to Paris. On paper, he found two SS Panzer “divisions” idling in Denmark. These, he ordered, must reinforce the Paris defenses. Warlimont, his operations chief, assured him that the two units would be in the Paris area by 25 or 26 August.

However, the divisions were anything but divisions. The so-called 26th SS Panzer Division was actually the 49th SS Panzergrenadier Brigade. The unit was north of Calais since 16 August, and not in Denmark when Hitler’s orders for deployment in Paris arrived.

The 27th SS Panzer Division was the 51st SS Panzergrenadier Brigade. It was formed in June with wheeled vehicles. The 51st Brigade’s reincarnation as the 27th SS Panzer Division occurred on 10 August, even though it had no tanks. Both brigades would find themselves deployed into position southeast of Paris by 22 August, some distance from the city.

Hitler’s faith that the city could be defended did not seep down onto even the most loyal of Nazis. All Gestapo files left the capital at the start of August. On the 17th, representatives of the pro-Nazi Vichy government under Pierre Laval followed. Then went the German embassy staff. (Joachim Ludewig, Ruckzug: The German Retreat from France, 141).

Laval himself left on the 19th.

Stulpnagel’s replacement, General Kitzinger and his higher military headquarters, also left the city on the 17th. (Ludewig, ibid.) Oberg fled on the 18th.

By 20 August, the Allied armies were over a hundred miles west of Paris. That same day, de Gaulle flew into Normandy to meet Eisenhower at SHAEF’s advanced headquarters at Granville. Eisenhower knew what de Gaulle wanted to see him about.

Before D-Day, during the Trident Conference, the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) had agreed to include a “token” French unit in the Operation “Overlord” troop list so that a French formation would be present at the liberation of Paris. (Vigneras, Marcel, Rearming the French, 171).

It was a political decision intended to cement the beginnings of a renewed and independent France. It appeared that de Gaulle intended to remind Eisenhower about this.