THE RESTLESS CITY

Meanwhile, back in Paris, the ceasefire was fraying by dawn on 22 August. Paris had endured 1,523 days of the German occupation and both the resistance and the populace were growing restless amid reports of Allied military units close by.

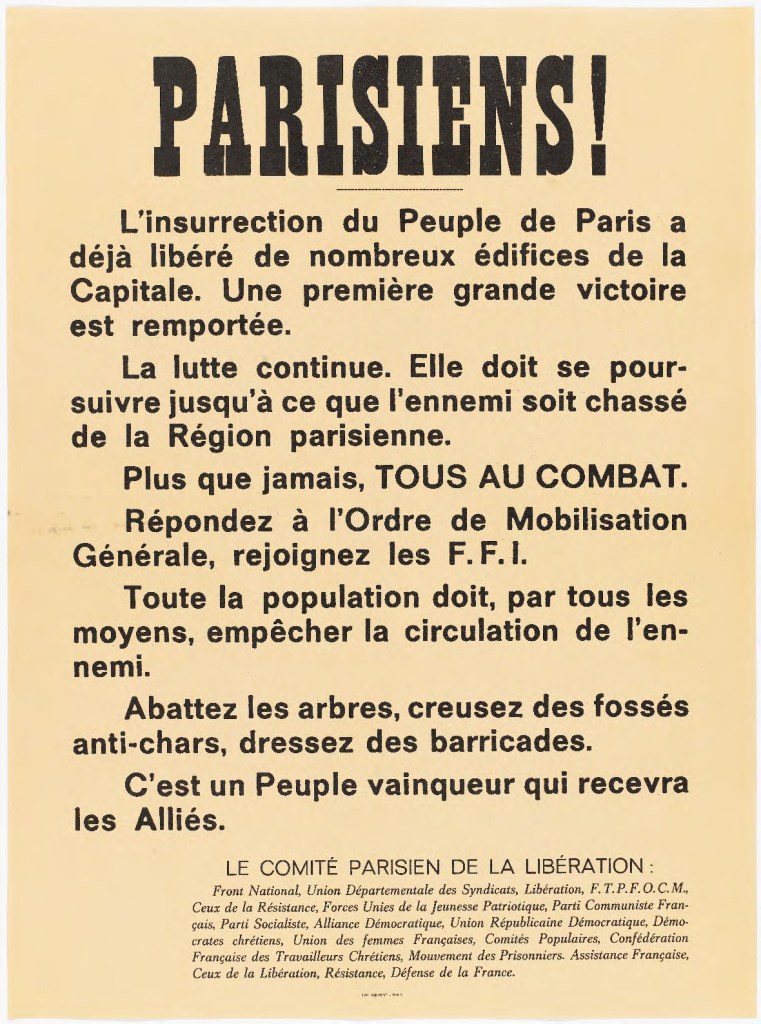

Sensing weakness in their German occupiers, the various resistance leaders, including Chaban-Delmas, agreed that the fighting must resume. An order was issued, written by Rol-Tanguy and signed by Parodi, calling for the immediate renewal of fighting and the building of barricades.

A poster, approved by Tanguy, called on the “whole Parisian population – men, women and children – to build barricades, chop down trees on all the main thoroughfares. Build barricades on the side-roads and make chicanes. To guarantee your defence against enemy attack, organise yourselves by street and by building. Under these conditions, the Hun will be isolated and surrounded in a few locations, and will no longer be able to carry out reprisals. Everyone to the Barricades.” (Cobb, 210)

The call aux barricades! was not unknown to Parisiens. It had been the call of civil action in 1830, 1848 and 1871. Now, Tanguy and the others called on Parisians to transform their city into a “fortified camp.” The resistance was short on arms so other FFI posters appeared, extolling the population: “Everyone get a Hun!” to be followed up by taking the slain German’s weapon and ammunition.

Another fear driving the Parisien haste for liberation were reports on Warsaw which suggested that Nazi and SS units were reducing the city to rubble following an uprising by General Bor-Komorowski’s Polish Home Army. German news footage of this was shown in the occupied territories. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 613.8, Ch. 9, 58%). With Paris also having instigated an uprising before Allied succor could be affected, the parallels were unmistakable and the implications stark.

As leader of the Paris Municipal Council, Pierre Taittinger discovered that von Choltitz was preparing key buildings and locations for demolition. He sought an immediate meeting with the General at von Choltitz’s opulent offices in the Hôtel Meurice. A bonafide collaborator who was said to have fleeced his coffers by supporting the deportation of the Jewish population of the city, Taittinger’s outrage had much to do with self-preservation.

The meeting did not get off to a good start. A belligerent von Choltitz said that he possessed the men and the means to turn Paris into another Warsaw. If one bullet was fired at a German soldier, the German general warned that he would “burn down every building in the block and shoot all their inhabitants.” This was more bluster than braggadocio. The resistance was already shooting at his men.

Shaken, Taittinger claimed that he took a moment to compose himself. He then asked Choltitz to imagine the day when he might stand upon the balcony of the Hôtel Meurice once again and gaze upon the city as a tourist — “and to be able to say, ‘Once, I could have destroyed all this, but I preserved it as a gift for humanity.’ General, is not that worth all a conqueror’s glory?” (Collins & Lapierre, 87).

Ordinary Parisiens had no inkling of this Vichyist’s plea. In their perception, their destiny lay in their own hands. Between 22 and 24 August, Parisiens erected over 600 barricades using vehicles, dug up cobblestones, barbed wire, piles of wood and even outdoor cafe furniture. Most of the barricades were built in working-class neighborhoods.

Only in the 16th Arrondissement, where the wealthy preferred to wait out the events and where German headquarters, billets, bunkers and troops were densest were the barricades the fewest. In the affluent 8th arrondissement, there were no barricades at all.

Meanwhile, the German frontline began fragmenting as the Allied armies moved forward. Field Marshal Walter Model, the new commander of OB West, found that he had lost contact with his XLIV Corps near Troyes, 180 km southeast of Paris. To Model’s consternation, the newly arrived German 48th Infantry Division was cut-off in the capital’s southern suburbs. This may have had something to do with the fact that the division had been poorly trained and had no real inclination for fighting. Many of its troops were Poles and other non-Germans. (See Samuel Mitcham Jr, German Order of Battle, Vol 1)

Model ordered the German 1st Army to defend the capital, in conjunction with those elements of the 48th Infantry Division that could be contacted. Meanwhile, the German 6th Parachute Division was instructed to liaise with von Choltitz. However, Model ordered von Choltitz to release over a dozen Tiger tanks for use elsewhere, but as a recompense, he installed a 2,000-troop-strong battlegroup under the Command of Colonel Hubertus von Aulock to defend the Seine bridgehead at Mantes. Aulock managed to locate his headquarters with some 200 men and tanks at Saint-Cloud, which would become important later.

In fact, the number of troops available to von Choltitz was declining by the hour. By the 22nd, he had less than 20,000 troops but which were strung out all across the city. The FFI assessed that the Germans had concentration of troops in just six places: the Hôtel Meurice; the Hôtel Majestic near the Arc de Triomphe, the House of Deputies (Palais Bourbon), the École Militaire, Senate and the Jardin du Luxembourg and the barracks on the Place de la République. (Cobb, 218) Choltitz’s tank force had dropped by nearly half to around 40, the FFI estimated.

But German armored patrols forayed across the city. On 22 August, two German tanks shelled the Hôtel de Ville from the Rue de Rivoli. The shelling smashed windows and scarred the face of the building. The FFI scrambled to evacuate women and non-combatants from the building when one of the tanks turned around and withdrew towards the Bastille. At about the same time, a convoy of German soldiers with an armored car in the vanguard appeared from the Quai de Gesvres.

The FFI, in the surrounding buildings, opened fire. The armored car came to a halt. An ammunition truck within the German convoy exploded. Alarmed, the Germans pulled back, leaving behind scores of weapons and munitions for the gleeful FFI. (https://liberation-de-paris.gilles-primout.fr/tous-a-lhotel-de-ville)

Meanwhile, south of Paris, it was around 9.30 am when Gallois was brought to the headquarters of the second most important American general in continental Europe: General Omar N Bradley, commander of US 12th Army Group.

The headquarters was at the Château du Bois-Gamats outside Laval. But Gallois had no time to admire the building. He was exhausted, having been driven 250 km overnight by a mute GI corporal. Here, the resistant was received by Bradley’s Chief of Staff, Major General Edwin Sibert. Gallois told his story once again and this time it was also heard by Bradley’s French liaison officer, Colonel Albert Lebel.

In a brief note intended for Eisenhower, Lebel wrote: “If the American Army, seeing Paris in a state of insurrection, does not come to its aid, it will be an omission the people of France will be unable to forget.” (Collins & Lapierre, 183)

Far from being swayed, the United States Army moved to curtail any movement towards Paris. As Leclerc was about to board a small plane bound for Laval, he was handed orders from his superior, Major General Gerow, demanding that Leclerc pull back Guillebon’s unauthorized reconnaissance towards Versailles.

Gerow had learned of this detachment’s unauthorized advance from multiple sources, including the Free French themselves. Aware that Gerow would discover the detachment’s movement towards Paris soon or later, Lerclec had dispatched his G-2, Major Philippe H Repiton-Préneuf, to Gerow’s headquarters on 22 August to explain that the insurrection in Paris made it necessary to advance the military detachment.

Gerow had also received a letter from the US Third Army demanding to know what French troops were doing outside their sector.

“I desire to make it clear to you,”Gerow wrote Leclerc in a letter he handed personally to Repiton, “that the 2d Armored Division (French) is under my command for all purposes and no part of it will be employed by you except in the execution of missions assigned by this headquarters.” (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 601)

To Gerow’s fury, Leclerc refused to recall Guillebon.

Leclerc also traveled to Bradley’s headquarters once again to ask that the 2e DB be formally released towards Paris.

By the time Leclerc arrived at Laval, Bradley had already left to visit Eisenhower who was himself visiting the First Army’s headquarters at Couterne. As Bradley walked into the headquarters, he declared that he had “momentous news that demanded instantaneous action”. (Cobb, 222)

In a letter to Bedell Smith days later, Eisenhower admitted that the Allies may “be compelled to go into Paris.” But in a cable to General George C Marshall, Chief of Staff of the US Army, Eisenhower insisted that liberating the capital could delay the encirclement of German forces in the Pas-de-Calais area.

After Bradley had briefed Eisenhower about the situation, the Supreme Allied Commander’s mind was made up. “It looks now as if we’d be compelled to go into Paris,” Eisenhower announced to the room. “Bradley and his G-2 think we can and must walk in.”

Eisenhower then turned to Bradley and said: “Well, what the hell, Brad. I guess we’ll have to go in.”

Bradley transmitted Eisenhower’s views in a memo to his officers, explaining that the Leclerc Division would be accompanied by forces from Gerow’s V Corps:

Paris was to be entered only in case the degree of the fighting was such that it could be overcome by light forces. In other words, he [Eisenhower] doesn’t want a severe fight to take place in Paris at this time… It must be emphasized in advance that this advance into Paris must not be by means of heavy fighting because the original plan was to bypass Paris on both sides and pinch it out. We do not want any bombing or artillery fire on the city if it can possibly be avoided… V Corps will advance without delay on Paris on two routes; take over Paris from the FFI; seize the crossing over the Seine south of the city; establish a bridgehead south-east of Paris.”

(Cobb, 222)

It was 6.15 pm when Bradley returned to Laval in his Piper Cub. He found Leclerc waiting impatiently. Over the past few hours, he and Major Repiton-Préneuf had been speaking with Gallois. The information Gallois presented had disturbed Leclerc. Pacing across the damp grass outside, Leclerc said over and over again: “I must have orders tonight.”

If orders did not come, it is likely that Leclerc would have broken the chain of command to send the division to Paris.

Before Leclerc, who was unaware of all that had transpired with Eisenhower, could open his mouth, Bradley interjected: “Ah, Leclerc! Good to see you. I was just about to give you the order to head for Paris.” (Cobb, ibid)

Leclerc was flabbergasted. With a quick introduction of Gallois to Bradley, Leclerc took off running for his own plane. When he landed at his headquarters at Fluere, southwest of Argentan, he saw just the man he was looking for: Captain Gribius, his Chief of Operations.

“‘Gribius!” he called. “Mouvement immédiat sur Paris! (Immediate movement towards Paris!’)” (Cobb, ibid)

An about-face order also arrived from Gerow, instructing Leclerc to secure the city by 24 August if possible. To support the 2e DB, the US 4th Infantry Division, the “Ivy Division,” would advance on Leclerc’s right and enter the city from Joinville and Vincennes. (Dansette, 258-59.)

When told that they were headed to Paris, some men of the 2e DB wept. Among them was Captain Charles d’Orgeix of the 12e Cuirassiers (RC), a tank regiment. A Parisian, d’Orgeix had been with a unit defending the city’s northern approaches in 1940 with just machineguns. He and his men had been routed. Now, the tables were turned. His Sherman M4A2 was prepared for the drive ahead. All the French tanks had nicknames and d’Orgeix’s Sherman was named “Paris.” (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 639.7, Ch. 10, 60%)

Among the soldiers came an intense desire for cleanliness. Wet clothes and razor blades transformed grimy men into a picture fit for ceremonial parade.

In the end, Leclerc had been vindicated in his struggle against Gerow. “The cold logic of tactics cannot make General Gerow understand the importance of Paris for our people who have lived for four years without hope,” Leclerc told his officers that night. (Captain Even, “La 2ème Division Blindée de son Débarquement en Normandie à la Libération de Paris,” Revue Historique de l’Armée, March 1952, 116)

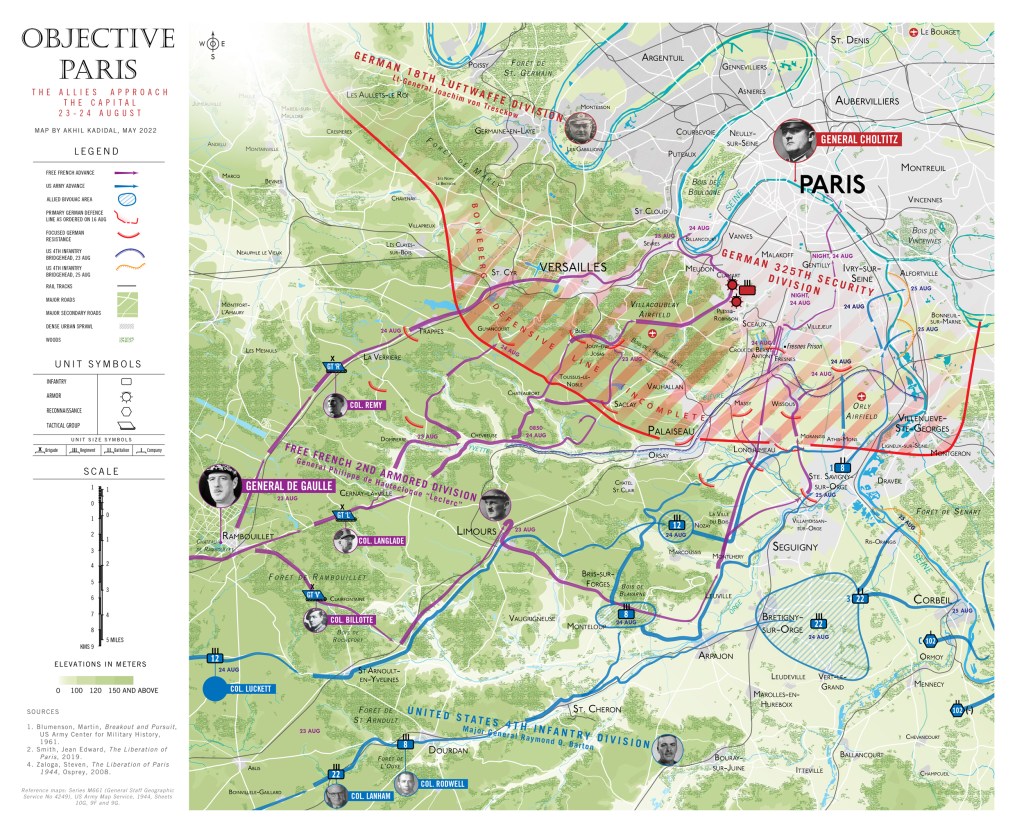

Meanwhile, Captain Gribius planned the advance. The division would advance towards the capital along two routes, through Sées, Mortagne, Châteauneuf-en-Thymerais, Maintenon and Rambouillet. Tactical-Group Billotte would make the main push from Mamers, Nogent-le-Rotrou, Chartres, Ablis and Limours.

Intelligence from Guillebon had revealed that the Germans had strong forces around Versailles. But Guillebon nevertheless received orders to advance through Versailles. (Cobb, 224)

By 6.30 am on 23rd August the 2e DB began moving out.

At 3 am, a colossal explosion rocked Paris. A Parisian, Micheline Bood, woke to find her building shaking like “jelly”. People rushed to their balconies to see what had happened. Voices rang out in the night: had the senate been blown up, were German V1 missiles landing? After moments of inconclusive bantering, Bood returned to bed. A massive gust of air gushed in from the east.

“It seemed that the dead body of Paris was swinging like a skeleton in the wind,” Bood wrote in her diary. “And there was this vast red glow, growing ever larger on the horizon… It was a dance macabre, a world of cataclysm and nightmare.” (Cobb, 231)

On the morning of 23 August, there was another explosion. This time, Parisiens could see that the Grand Palais was on fire. The palace was hosting the Houcke Circus. French policemen loyal to the resistance in a building next to the palace had opened fire on a passing German patrol. To the Germans, the firing appeared to come from the Palace. Soon, the palace was under siege by two Tiger tanks, and an armored car. Unsatisfied, the Germans brought up two “Goliaths,” a small, remotely controlled tracked vehicle packed with 75 kgs of high explosives.

Both Goliaths were sent into the palace. At least one was detonated. The resulting explosion shattered part of the glass dome. Smoke began to pour out of the doors and the roof, so thick, that the entire city could see it.

The circus was finished.

A dispatch from Hitler arrived for von Choltitz at the Hôtel Meurice. “The strongest possible measures” are to be taken, including “blowing up whole city blocks, public executions of ringleaders, and complete evacuation of the affected district,” Hitler wrote. “The Seine bridges are to be prepared for demolition. Paris is not to fall into enemy hands other than as a heap of rubble,” he ordered. (Cobb, 232)

Choltitz showed the order to his aide, Oberst (Colonel) Hans Jay. The erudite and refined Jay was lost for words. He gazed at the Jardin du Tuileries which was bathed in sunlight, and then at the magnificent plaza of the Concorde and the architecture of the Louvre. “The scene merely underlined the madness of this medieval command,” he would write later.

Even von Choltitz seethed inwardly at Hitler’s order. “I was ashamed to face my people,” he would say, days later. (Cobb, ibid)

Meanwhile, Leclerc’s forward units reached Rambouillet at about 1 pm. (Cobb, 251). Following behind was a motely group of combatants, intelligence personnel and hangers-on led by Colonel Bruce and the writer, Ernest Hemingway. This eclectic crew of 54 men, included two AWOL paratroopers (who at the time were also inebriated), 10 resistance members and 14 gendarmes. (Carlos Baker, Ernest Hemingway, 410)

Guillebon’s group, meanwhile, having been cut off from the division and having no inkling that Lerclerc had finally been cleared to go to Paris, was driving back southwest from a Parisian suburb, Arpajon. The unit arrived at Rambouillet at 9 am – and sent out units towards Versailles.

Colonel Bruce warned Guillebon of German forces to the north. But Guillebon pushed on. As the French approached the outskirts of Versailles, a German tank shell struck the leading vehicle, an M8 Scott Howitzer self-propelled gun named Le Sanglier (Wild Boar).

Le Sanglier’s gunner André Perry responded by firing three rounds at German tanks that had appeared out of nowhere. Almost immediately, the M8 Scott buffeted as it took three fearsome hits. A fourth shock appeared to obliterate the M8.

“As I opened my mouth to ask the young gun-loader what was happening, he collapsed on top of me,” Perry said. “At the same time, everything burst into flames and my comrades began to moan or scream. We had been hit.”

While he felt no pain, Perry sensed blood running down his face and into his mouth. He screamed at the gun-loader to get out of the turret but the man did not budge. Perry grabbed him and pushed him out of the open turret.

“Then I dived back in to try and get the driver and the radio operator. Because of the flames and exploding ammunition, I couldn’t get to them. It felt like I was in hell; suffocating, and with my clothes on fire, I managed to get out. As I collapsed outside my eyes fell on a road sign that read: Paris, 36 km,” Perry said. (Cobb, 250)

Three of Le Sanglier’s M8 Scott’s five-man crew were dead. Perry had survived.

Back at Rambouillet an hour later, Colonel Bruce was astonished to see a troop from Guillebon’s force return, minus one vehicle and two men dead. The troop leader, Lt. Bergamain of the 1st Spahis Marocains Regiment, was a bloody mess. He had been shot in the back, arm and leg.

As Bruce and Hemngway plied Bergamain with a bottle of champagne, Lerclerc pulled up in a jeep. (Lankford, 168) It was about 1 pm. Bruce briefed Major Repiton on German dispositions up the road. But seeing Hemingway and other journalists, Leclerc appeared annoyed.

Colonel Bruce said that a veritable press corps had filtered into Rambouillet from the morning of the 23rd and were hungry for a story. They were irritated with Leclerc for not telling them his plans for Paris. (Lankford, 169) Lerclerc is said to have muttered: “Buzz off you unspeakables!” (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 642.3, Ch. 10, 60%).

This wounded Hemingway. Until Leclerc’s death in 1947, Hemingway would remember the general as “That jerk Leclerc.” (Baker, 413)

By now, while he was still Chartres, Leclerc had dispatched one of his officers, Captain Andre Janney (an officer of the 501e RCC who had a penchant for volunteering for dangerous missions), to inform de Gaulle about the situation: that Guillebon had been confronted by a “good many Germans in the Trappes sector” and “even if the FFI have liberated inner Paris” there will have to be fighting by the 2nd Armored.

“I shall therefore begin the operation at dawn tomorrow,” Leclerc added.

De Gaulle responded as Napoleon would respond to his favorite General, Marshal Jean Lannes. (Jean Lacouture, De Gaulle: The Rebel 1890–1944, 568)

I have received Captain Janney and your note.

I should like to see you today.

I expect to be at Rambouillet this evening and to see you there.

I embrace you.

De Gaulle arrived in Rambouillet soon enough. There, he was told by Leclerc of a new plan of action to take Paris: Langlade’s combat command would enter Paris through Clamart and the Pont d’Sevres in the west, but the prize of capturing central Paris would go to Colonel Pierre Billotte, de Gaulle’s “closest military colleague.” (Lacoutre, ibid).

Billotte and his reinforced tactical group would pierce the German defenses around Paris from the south. Political favoritism had played a role in the attack plan as well, but it was one that would turn out to have been prudently made.

Two units, the 501e RCC and Major (acting Lt Colonel) Joseph Putz’s 3rd Battalion of the RMT, belonged to Billotte’s combat command. These two units would show their mettle in one of the storied military engagements of the war.

INTO PARIS

By the time the 2nd Division roused from its slumber the following morning, on 24 August, from tents and makeshift vehicle bivouacs, the air was moist. It had rained and the surrounding forest of Rambouillet amplified the wetness. Leclerc, de Gaulle and some men had slept in the magnificent Château de Rambouillet.

The division became a hub of activity. Billotte’s Command pushed on towards Arpajon even as a detachment of reconnaissance troops (the Spahis Marocains) under Major Francois Morel-Deville once again set off towards Trappes and Versailles. Morel-Deville’s movement was a feint to cover Billotte’s thrust towards the city.

Lerclec’s headquarters followed behind Bilotte. The cohesion of the squadron into a three-pronged serpentine force left Colonel Bruce impressed. We “passed miles of tanks, trucks etc. of the Second Armored Division… these Frenchmen look extremely tough and fit”, he wrote in his diary. (Lankford, 170)

A BBC report in the morning declared that Patton’s Third Army had taken Paris. It had not. In his diary, Patton said that the report “will be refuted, but no one will pay any attention.” (Blumenson, The Patton Papers, Loc. 881.4, Ch. 29, 59%)

Meanwhile, sparks were flying once again in Gerow’s headquarters. Leclerc’s new plan of advance cut across the approach routes of the US 4th Infantry Division which had been dispatched to secure areas south of Paris.

The Americans had thought-out their supply and logistical details based on the assumption that the 2e DB would make the effort towards Paris from Rambouillet through Versailles. The new French route of advance interfered with the US lines of advance and muddled cogent support for the Free French from US tank and artillery forces. History, however, would record that Leclerc’s decision to primarily breach Paris from the south rather than from the west was correct. The German defenses in the south were weaker. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 610-612)

However, Gerow interpreted Leclerc’s actions as a statement of defiance towards American command — and potentially intended to slow the advance of the US 4th Infantry Division. Already, Gerow had started to call Leclerc that “miserable man.”

A battlegroup commanded by Lt-Colonel Jacques Massu (under Tactical Group ‘L’ led by Paul de Langlade) departed Châteaufort at dawn. Massu, who had a large proboscis, was beloved by his troops who knew him as “the king of noses.” Massu was also involved in a relationship with one of the Rochambelles, the acting commander of the unit, Suzanne Torrès.

At the point of GT ‘L” was a section (platoon) of Shermans from the 12e RCA. The advancing force began to take sporadic machine gun and sniper fire but then stumbled upon a minefield and artillery fire beyond Châteaufort. As they came upon the village of Toussus-le-Noble perched on a low plateau, they found the place deserted. The Germans had blocked the northern exit with debris, to force the Shermans the vehicles into neighboring fields, where anti-tank guns waited.

As the armored column clanked up the grassy slope, the Germans opened fire. Large 88mm shells mixed with MG42 machine gun fire. An 88m shell plunged into a Sherman M4A2 nicknamed Ardennes. The tank stopped. A second 88mm shell crashed into the tank. The Sherman burst into flames but the crew scrambled out of the wreck and lived to fight another day. The French began lobbing 105mm shells at the enemy lines. The RMT infantry joined in with furious small-arms fire.

Three Shermans from the 12th RCA were soon on fire. Infantrymen of the RMT were sent to clear the woods across the river. Hours would pass before they would winkle out “a dozen” German anti-tank guns. It was 11 am before the route was clear once again.

In the meantime, De Langlade ordered his second battlegroup, commanded by the portly Lt-Colonel Jules Minjonnet to outflank the German position by heading towards Saclay and Jouy-en-Josas. Captain Gaston Hargous’ 4th Squadron (12e RCA) was handed the job of leading this pincer. Supporting the tanks were the RMT infantry of Captain Fonde’s 7th Company, led by Lieutenants Guigon, Miscault and Maret. Major Mirambeau’s artillery units were assigned to support this pincer.

Within this battlegroup was a formidable M4A3 (76) Sherman commanded by Aspirant (officer aspirant) Jean Armand Zagrodski of the 12e RCA. Emblazoned across the side of the tank was its name: Lt. Zagrodski – in homage to Jean’s older brother, Michel, who had been killed in action at Alencon on 10 August.

With the RMT infantry in tow, Zagrodski’s troop rumbled over a beet field to reach the Saclay canal. The tanks crossed the shallow canal in a fighting advance, shooting at anything that shot at them. A farmer’s barn full of harvest caught fire in the crossfire, the brilliant light of the flames shining like a torch. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 668, Ch. 7, 66%)

Beyond the village, Lt. Guichard of the RMT was hit in the chest with machine gunfire, as were two of his men. Soon, the force of German fire had become so intense that the advance had stalled. Captain Fonde called a retreat back to Jouy. Fonde had decided they would force their way through the grimly named Bois de l’Homme Mort (Woods of the Dead Man).

A villager at Jouy told Fonde that the Germans were positioning several anti-tank guns on the high ground in the forest, at the crossroads of l’Homme Mort.

“‘Positioning’ or ‘have positioned’?” Fonde asked.

“The Germans have not yet finished digging in,” the villager said.

However, having already dispatched a platoon of infantry under Lt Guigon towards the cross-roads, Fonde and Zagrodski’s Shermans set off to reinforce Guigon with the villager acting as a guide.

A hundred meters from the forest, the villager yelled, pointing to a place in the forest: “They are there.” Fonde could see the muzzle of an 88mm cannon sticking out of the foliage. Zagrodski saw it too. His crew opened up with their machine guns at the Germans

The 88mm gun barked and a shell flamed past the Sherman. Fonde ran towards the Sherman to direct Zagrodski’s fire. A second 88mm shell plowed into the road, sending a fragment of metal from the blast tearing into Fonde’s thigh. The captain cried out and fell.

As he was being evacuated to the rear, Fonde ordered Lt. Maret to take out the 88mm gun. Lt Maret’s platoon reached the gun just in time to see a shell from Lt. Zagrodski shatter the German cannon’s barrel. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 670.2, Ch 7, 66%)

The Sherman next destroyed a 75mm PaK anti-tank cannon. The Germans respond by hurling grenades at the infantry and tanks. The Lt. Zagrodski began taking heavy fire from a German Sdkfz 7/2 halftrack with a 37mm ack-ack gun. Shells began ricocheting off the metallic hulk of the Sherman like a swarm of fireflies racing in all directions.

Zagrodski peeked out of the turret to assess the situation. A 37mm shell struck him in the head and killed him instantly. The Zagrodski family had made the greatest sacrifice for France.

Note: The Sherman was later found pockmarked with 42 hits. (2e DB Forum: https://2db.forumactif.com/t5279-sherman-m4a3-76-mm-lt-zagrodski?highlight=Zagrodski , accessed 28 Aug 22)

Following this appalling loss, Langlade’s tactical group next began taking fire from German tanks deployed in the Bois de Meudon and at the Chatillon crossroads. In the midst of this battle, French civilians emerged en masse to greet the French soldiers.

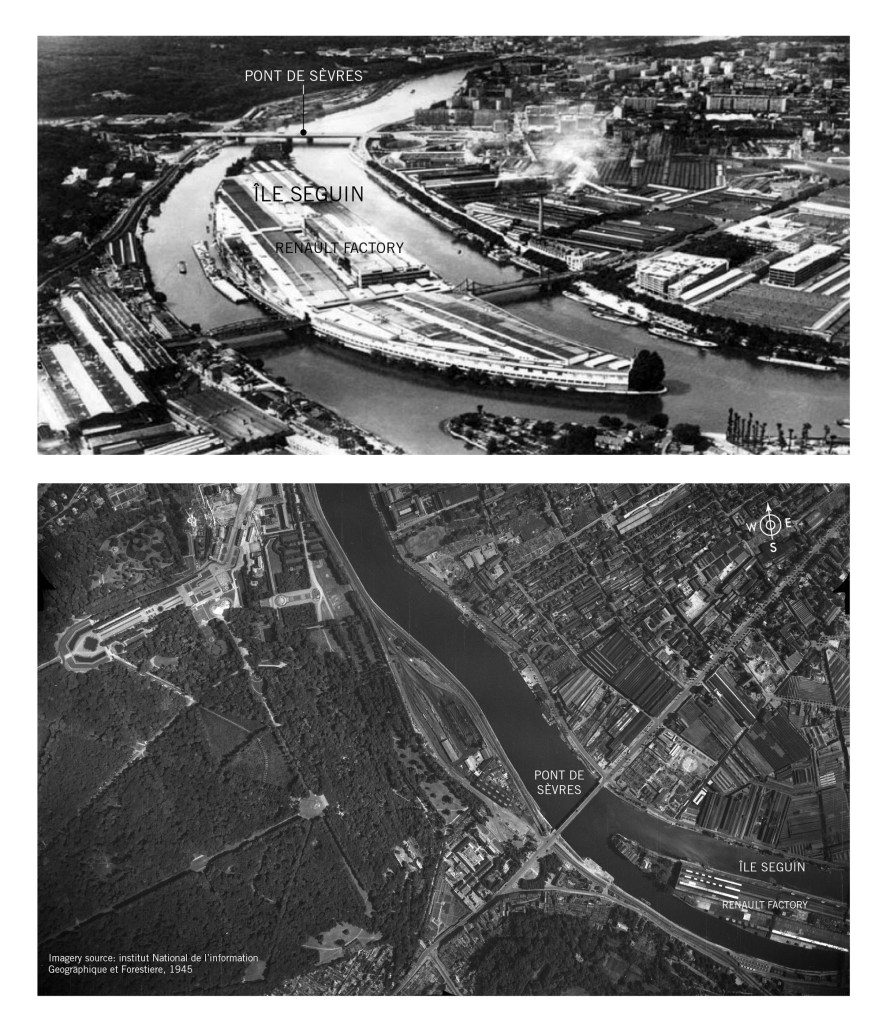

The troops tried to wave back the civilians, shouting: “Not now! We love you too, but let us pass.” (Dansette, 266). It was 9.30 pm before Tactical Group Langlade reached its objective – the bridge at Sèvres over the Seine river, only two kilometers from the south-western edge of Paris. By midnight, Massu’s battlegroup was occupying both sides of the riverbank. Having led the vanguard was ‘B’ Troop of the US Army’s 102nd Cavalry Group, under a Captain Peterson.

A journalist from the resistance newspaper, Le Franc-Tireur, described the scene in an article:

It all happened in a flash. First the place was empty then, without warning, the bridge was full of tanks, real tanks, and not simply young men armed with rifles and revolvers. The lads of Leclerc’s army are here. The tanks are covered with young girls, with women who are hugging these first uniformed men of the French Army. They get down from their tanks. They move among the crowd which presses around them to hail them, to thank them for being there. I push my way through the madding crowd, a crowd that is crying for joy, and which can do nothing other than cry its joy. All of a sudden, the electricity came on and the streets were flooded with light, the river below the bridge flashing as the reflections danced in the water.

(Cobb, 273)

Langlade set up his headquarters at a cafe on the Île Seguin, near a Renault factory. He then sought out a telephone and called his mother in Paris. He told her that he would see her the following afternoon. (Jean Smith, The Liberation of Paris, loc. 260.7, Ch. 7, 59%) But Massu was ready to go into the heart of Paris that same night.

“That is not your mission,” de Langlade told him. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, 61%) But for one company in Colonel Pierre Billotte’s Tactical Group ‘V’ (GT V), this became precisely their ad-hoc mission.

GT V had set out on the road at the same time as Langlade’s Tactical Group ‘L’. GT V’ made rapid progress over National Highway 20, spanning Orleans and Paris. In the vanguard was Lt-Colonel Putz’s 3rd Battalion (RMT). The tactical group went through Arpajon and Monthéry without incident. At Ballainvilliers, their problems began. The town was a prelude to frequent roadblocks and traffic snarls caused by ecstatic French crowds.

As the Tactical Group went through Longjumeau, the cobbled roads were slick with drizzly rain. Ecstatic French civilians stood by their front doors or leaned outside their windows while the column went through. But the progress was not fast enough for some.

US highway command was becoming frustrated at what it regarded as the slow advance of the division. Even the resistance in Paris was chafing at the seemingly slow progress of the 2e DB. At Longjumeau, amid stalled traffic, Leclerc was confronted by a policeman who informed him that he had a caller on a phone nearby.

Leclerc asked Colonel Jean Crépin, the head of the divisional artillery, to take the call. Crépin found that the man calling was Charles Luizet, the newly prefect of police in Paris. Barricaded at the Prefecture of Police, Luizet’s command was running low on ammunition. To Crépin, he begged for the 2nd Division to hurry up before ammunition ran out. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 651.1, Ch. 10, 61%)

To US commanders, it seemed incredible that Leclerc had not yet taken the capital. Unaware of the difficulties on the ground and believing that the Germans were withdrawing, US commanders believed Leclerc was procrastinating.

In a letter from Gerow to the US Office of the Chief of Military History (OCMH) in 1954, it was claimed that Leclerc’s inability to move rapidly on 24 August was due to his unwillingness to “jeopardize French lives and property by the use of means necessary to speed the advance,” which stood in contravention to orders which declared that restrictions on the bombing and shelling of Paris did not apply to the suburbs. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 613)

Bradley was equally unsympathetic, writing that French troops had “stumbled reluctantly through a Gallic wall as townsfolk along the line of march slowed the French advance with wine and celebration.” (Bradley, Soldier’s Story, 392)

Gerow requested authority to send the US 4th Infantry Division into Paris. An order to this effect might “shame Leclerc into greater activity and increased effort,” Gerow thought. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 613-614).

Bradley finally decided that he “could not wait for the French ‘to dance their way to Paris’.” To his staff, he said: “To hell with prestige, tell the Fourth to slam on in and take the liberation.” (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 613-61 & Bradley, 392)

The 4th Division staff had no idea of the machinations brewing at US army corps and army headquarters. To the divisional commander, Major General Raymond O Barton, the new orders to get into Paris was a “normal procedure of reinforcing a unit that was having unexpected difficulty with an enemy who was not withdrawing.” (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 614)

It was true that there was wine and dance on the way to Paris, but also horror. A beautiful girl approached a 501e RCC Sherman of Battlegroup Putz. Captain Raymond Dronne, commander of the 9th Company (of the RMT) saw a German machine gun pepper the tank, the bullets bouncing off the armor in brilliant swarming flashes. The girl was caught in the fusillade. She fell, her dress snagging on the tank’s tracks as he plummeted earthwards, the cloth replete with bloody bullet holes. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 651.1, Ch. 10, 61%)

By the late afternoon of the 24th, Choltitz was reporting to his superiors that the French had broken through forty tanks and were heading for Paris. (Ludewig, 146)

Congrats, how ever your articles are awesome. Your graphics are impressive!!! Greetings from South of Spain

Thank you. I appreciate your words!

AWESOME COVERAGE, FIRST EVER OF COMPLETE STORY BATTLE OF PARIS 1944, MERCI BEAUCOUP!!!!!!

Thanks, Eric. Appreciate the support.

No one word about Spanish Company “La Nueve” who was the first in go in to Paris and support resistance.

Read on. They are in there.

Hello Akhil, for these two photos:

“Dronne’s second-in-command of the 9th Company was Lt. Amado Grannell. He is seen here leading a patrol in Normandy. Curiously, he is armed with a German MP.40 submachinegun. (photo source unknown)“

We are not in Normandy, my caption: “Photo Krementchousky n° 1329 – Le Lt Amado Granell en patrouille, de Xaffévillers à Ménarmont (9ème compagnie du IIIème bataillon du RMT)” (Musée de la Libération de Paris – musée du général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin, Paris Musées)

“Lt-Colonel Jacques Massu, commander of the 2nd Battalion of the Régiment de marche du Tchad (RMT), rides as a passenger in a jeep executing a high speed turn through a Norman village – en-route to Paris. Although there has been some dispute that man in this photograph is not Massu, a close inspection of the facial features, the clothing and even the goggles, suggests that it is. (photo from “Du Tchad au Rhin,” Vol 3, L‘Armée Française dans la Guerre, 1945)“

We are in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, here is my caption: “Le commandant Jacques Massu – cdt du IIe bataillon du RMT – à bord de la Jeep “Moïdo” (413353) du II RMT de la 2e DB, conduite par Georges Hipp (FFL), à Pierrefitte-sur-Seine : venant de la redoute de la Butte-Pinson via l’avenue de la République, celle-ci tourne dans la rue de Paris/av. Général-Galliéni et se dirige vers Sarcelles”

Thanks, Guilhem. I have amended the captions. Good to get this information!

Dear Sir,

The photo:

“A German force, comprising two Panther tanks and several infantry attack the Prefecture of Police. Despite having 20,000 troops in Paris, the Germans were strung out. Their inability to mass infantry meant that von Choltitz could not overrun the prefecture. (photo source unknown)“

– which can notably be found at the IWM and at the Archives de la Somme – is not from 1944, but rather from 1947: they were filming a movie (see another photo Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images n° 1264105834). The Notre-Dame’s scaffolding was not there in 1944.

Cheers,

Guilhem Touratier

Hello Guilhem, thank you for this information. I really appreciate it and I have corrected the image caption. What is the name of this 1947 film? I would be interested in watching it.

Hello Akhil, you are welcome, it is with pleasure. Thank you for the correction. Unfortunately I do not know the name of this film…

Hello Akhil, thanks to a colleague, the film is that one: “Un flic”. Un flic (1947) – IMDb

Thanks, Guilhem. I will try to track down a copy of this film. I am astonished to learn that this is a crime/gangster movie.

Good afternoon Mr Kadidal,

concerning Lt-Colonel Massu I confirm that it is this man, those who say it is not him should go see their eye doctor. I have worked 20 years for my books on the liberation of Paris and have many photos of this officer and can tell you that it is him in his jeep.

Laurent FOURNIER

main author of “La 2e DB dans la libération de Paris et de sa région”

Thank you, Laurent. Good to hear from you again!