CONFLUENCE

By mid-afternoon, Colonel Bruce, Hemingway and their entourage had arrived in the capital – on the heels of GT Langlade.

Finding that the Champs Élysées was devoid of road traffic, the group raced towards the Travellers’ Club, set in the Hôtel de la Païva. Hemingway’s biographer, Carlos Baker wrote that all the rooms in the building were locked except for the bar where the elderly French president of the club and several members were drinking.

“Since the Americans were the first outsiders to reach the Club, a testimonial bottle of champagne was quickly opened and toasts offered. As they drank, a sniper began to fire from an adjoining roof.” (Baker, 634)

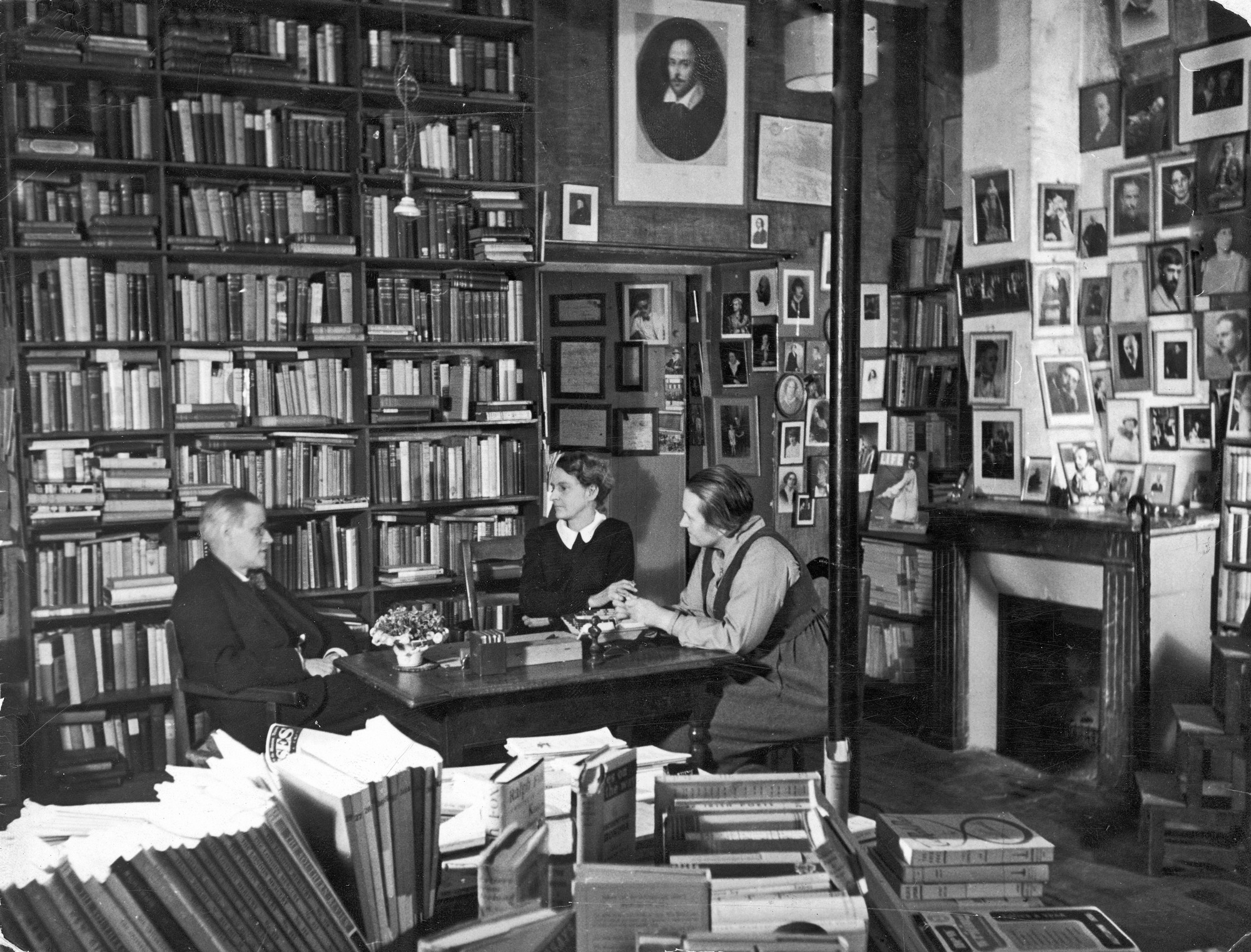

Hemingway and Bruce then made for the Café de la Paix. Hemingway then temporarily parted ways with Bruce to visit Pablo Picasso at his studio on the Rue des Grands Augustins. Picasso was not at home – he was still on the Ile de Saint-Louis with Marie-Thérèse Walter. Thwarted, Hemingway then decided to visit Sylvia Beach, the American owner of the bookshop Shakespeare and Company on the Rue de l’Odéon, which had been the watering hole of the expat literary community before the war. The bookshop, which the Nazis had closed during the war, was just a short distance from the Jardin du Luxembourg.

It is unsure if Beach and her neighbors had heard the terrific din of battle raging at the Jardin. But that evening, she did hear neighbors shouting that a column of Jeeps were coming down the street.

Then she heard “a deep voice calling ‘Sylvia!’”

Seconds later, everyone in the street took up the cry ‘Sylvia!’

Beach’s companion, Adrienne burst into the room and said: “It’s Hemingway!”

Beach found herself flying down – and crashing headlong into Hemingway who was coming up the stairs.

“He picked me up and swung me around and kissed me while people on the street and in the windows cheered.” (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 745.5, Ch 7, 74%)

Beach took Hemingway upstairs. She gave him her last bar of soap so that he could wash the grime of the journey away. When Hemingway asked if he could do anything for her, she said that German snipers were on the roofs of buildings on the street. Could anything be done about them?

Hemingway and his band went up on the roof and for a moment, Beach could hire gunfire. Shortly after, Hemingway came down, bid Beach farewell and raced off northwards again with his men to “liberate the cellar at the Ritz.” He entered the hotel through the Rue Cambon entrance with shouts of “Raus” as if he expected a platoon of Germans to be waiting for him.

Instead he found surprised hotel patrons, including some British gaping at him. He made his way to the cellar for a drink. (Moore, Paris ‘44, ibid)

Later that evening, when all the shooting had died down, Sergeant Salinger made his way to the Ritz, having heard among the soldiers’ scuttlebutt that the great man was ensconced in a room and receiving visitors. Whatever vagaries of fate were at play, it was decided that Hemingway should gaze upon the dark-haired sergeant, a man 20 years his junior, but with a face he recognized from Esquire. For Salinger, the visage of Hemingway in turn, was like that of a minor God.

Salinger had brought along a copy of the 15 July 1944 edition of Saturday Evening Post. This contained his latest short story, “Last Day of the Last Furlough.” Salinger told Hemingway that he admired his work, and although Hemingway had heard all these words before from others more luminous, he was surprisingly friendly and gracious to Salinger.

Hemingway read the “Last Day of the Last Furlough” at once. The story, about two US Army draftees interacting with their families before they are shipped off to war, impressed Hemingway who was already impressed by this infantryman. Salinger appeared to embody Hemingway’s romantic notions about the American fighting man in World War II.

One line in the “Last Day of the Last Furlough” perhaps stood out for Hemingway:

Vincent smiled. “It’s good to see you, Babe. Thanks for asking me. GIs — especially GIs who are friends — belong together these days. It’s no good being with civilians any more. They don’t know what we know and we’re no longer used to what they know. It doesn’t work out so hot.” (Salinger, Twenty-One Stories: The Complete Uncollected Short Stories of J D Salinger, Vol. I, 46)

Carlos Baker would write that Salinger returned to his unit in a state of “mild exaltation”. In a letter to a friend, Salinger would say that he found Hemingway “modest” and “not big shotty”. It is unclear how much of an impact the meeting had on Salinger’s growth as a writer. Arguably, Salinger’s talent (emulated from Hemingway’s minimalistic style) had already started to surpass Hemingway’s own.

In her memoir Running with the Bulls, Hemingway’s posthumous daughter-in-law, Valerie, would write that: “The contemporary American authors Hemingway most admired were J D Salinger, Carson McCullers and Truman Capote.” (Shields & Salerno, loc. 208, Ch. 3, 17%) After the war, Hemingway would treasure a copy of The Catcher in the Rye. (Paul Alexander, Salinger, Loc. 134.3, Ch. 6, 27%)

NIGHT FALLS

By now, British Commandos of 30 Assault Unit (AU) had also entered the city via the Porte d’Orleans.

The 30 AU’s ‘X’ Troop with 75 men turned west at the Place Victor Basch and headed in the direction of the Pont Mirabeau. An apartment block adjacent to the bridge was the objective. Allied intelligence believed that this apartment building housed U-boat offices. But when the commandos swept he building they found only meteorological equipment and billets for Kriegsmarine personnel. (Craig Cabell, History of 30 Assault Unit, Pen & Sword, 2009, loc.193.7, Ch. 19. Cabell claims the unit entered Porte d’Orleans at 4.30 pm)

The troop next headed to the Château de la Muette. Built by the Baron de Rothschild in 1931, the honey-colored chateau was a complex of “big-windowed, modernist flats”. (Rankin, loc. 443.1, Ch. 12). The Kriegsmarine had requisitioned the building in 1941 plus the Rothschild estates (a series of five-story apartment blocks at No 2 Boulevard Suchet) across the road.

Allied intelligence thought that the chateau was the HQ of the Kriegesmarine in France, the Oberbefehlshaber des Marinegruppenkommandos West. In reality, the Chateau was mostly being used to conduct refresher courses for submariners. The estates were painted in camouflage green and given two bunkers facing the Bois de Boulogne.

As the commandos approached, the estates were strangely silent. But they heard muted sounds of gunfire from the direction of the Chateau.

A burst of 20 mm ack-ack fire bounced off the slanted edge of Corporal Bon Royle’s halftrack. The commandos scrambled to take up firing positions. It was the beginning of a two-hour battle with the Kriegsmarine.

The British troop’s Staghound armored cars appeared and began to pummel the German positions. The troop, commanded by Captain Geoff Pike advanced on the Chateau. The Germans waved a white flag. It was about 9 pm. It is possible that the garrison had finally learned that von Choltitz had surrendered.

Now, came the difficult proposition of convincing the Germans that their decision to surrender to a smaller force had been the correct one. Colonel Woolley gathered the troop to give the impression of numerical strength.

The Germans emerged from the chateau with their hands up. The commandos were stunned to find that they had 560 captives on their hands. (Nicholas Rankin, Ian Fleming’s Commandos, Faber & Faber 2011, loc. 441.7, Ch. 12)

To the horror of the Germans, the commandos placed them in the custody of FFI militiamen who appeared on the scene. To compound the horror of the sailors, the commandos gave the FFI a cache of German weapons. It is unclear what happened to the prisoners. The commandos settled in for the night at the Chateau.

In the next few days, they would romp across Paris and beyond in search of Kriegsmarine secrets. At 43 Avenue Maréchal Fayolle, a villa which belonged to an Argentine, they found a Kriegsmarine cipher headquarters, complete with “coding areas, the teleprinters, and a concrete Kriegsmarine communications room with secure landlines to every major port and submarine base in France, Belgium and Holland as well as Berlin, Hamburg, Kiel, Cologne and Wilhelmshaven.” (Rankin, ibid)

Following on the heels of the British commandos was an associated specialist unit: ‘T-Force’ (Target Force), which was part of a joint US-Britain mission to seize technologically-important German equipment and key personnel. The unit, which consisted of 1,805 personnel (including 1,057 combat troops – out of which 77 were from 30AU and the 80 from the French Special Air Service (SAS)), also had the capability to defuse mines, booby-traps and explosives. About 548 personnel originated from the 10 allied intelligence agencies. This included 63 from teams sent by the Combined Intelligence Priorities Committee and 18 from the so-called Alsos Mission which investigated German scientific developments.

The ad-hoc unit was attached to General Bradley’s US 12th Army Group and commanded by Colonel Francis P Tompkins. (Douglas Botting & Ian Sayer, America’s Secret Army, 146) To scour the capital for German scientists, officials and technology, 14 inspection teams had been formed. (Sean Longden, T-Force: The Race for Nazi War Secrets, Loc. 72.4, Ch 2, 10%)

The unit’s secondary objective was to gather intelligence documents on the French political class to determine the extent of collaboration with the Nazis. The unit arrived in the city at around 10 pm with the objective of securing 514 “personality targets”. Elements of 30AU also shared this mission.

The unit set up base at the Petit Palais and went about its task. However, it found that the Free French and the French Resistance had already taken many of the targets into custody and that many French technical staff on the target list had been killed by the resistance on charges of collaboration with the Germans. T-Force’s executive officer, Lt-Colonel Harold C Lyon, of the US Army, wrote that over the next 48 hours, T-Force would be able to arrest only eleven individuals. (Cobb, 316)

The surrenders continued across Paris, despite a justified and acute horror among Germans about how they would fare after they laid guns down. Jacques Bardoux, a member of the French senate since 1940, estimated that 40 Germans were killed after they had surrendered. (Bardoux, La Délivrance de Paris, 366) In many cases, the Parisian hostility was passive but overwhelming. Lines of prisoners were subject to choruses of the La Marseillaise.

The singing erupted from beyond a mere need to mock the Germans. The journalist A J Liebling wrote in his dispatches that the city had been overcome with joy. The Spanish exile, Victoria Kent added that, “We clap our hands and hold them out to our liberators. We would like to do more. We would like to put the tanks on our shoulders and take them through Paris, from the north to the south, from the east to the west, but all we can do is smile and hold out our hands.” (Cobb, 296)

The French even put aside their traditional hostility of the British. Said Dennis Woodcock, a member of the 2e DB’s Quaker detachment of stretcher-bearers:

Paris was absolutely fantastic. Men of the 2e DB could have anything they wanted, absolutely anything. Whatever shops they went into, or restaurants, or cafés, or wherever they went, the people would insist they had anything it was humanly possible to provide. The great affection and admiration the people had for the British was tremendously apparent. If they were prepared to give everything in their power to the French soldiers then it would be true to say this was doubly so as far as the British were concerned.

(Henry Maule, Out of the Sand, Odhams 1964, 227-228)

At the Ministry of War, de Gaulle was still dithering about going to the Hôtel de Ville – despite invitations from Rol-Tanguy and the Communists. Convinced that the CNR and the communists were directly challenging “his authority” De Gaulle told Parodi that he had “no intention of being ‘received’ by the CNR or the CPL.” (Collins & Lapierre, 332) He also regarded the Hôtel de Ville as a mere symbol of the municipal authority.

A dismayed Parodi knew instantly that de Gaulle’s failure to appear at the Hôtel de Ville would cause a rift between the Gaullist and CNR factions. He asked Luizet to intervene. After a lengthy tête-à-tête, de Gaulle finally agreed to visit the Hôtel de Ville after he was told a massive crowd had mustered outside the Hôtel to await his appearance.

In agreeing to visit the Hôtel, de Gaulle had also obtained a key concession. He would first visit that Gaullist symbol of the uprising – the Prefecture of Police. The visit to the Prefecture had the added benefit of cementing police support for de Gaulle. Some 800 police who had held the prefecture for the last seven days were enthralled by de Gaulle. Their role in the uprising is today marked by the red lanyards found in the formal ceremonial dress of senior Paris police officers.

It was about 7.15 pm when de Gaulle finally appeared at the Hôtel de Ville. He was immediately annoyed to find that Bidault and the CNR wanted him to re-proclaim the republic. To the Bidault’s surprise, de Gaulle said: “No. The Republic has never ceased to exist. Free France, Fighting France, the French Committee for National Liberation, have, in their turn, been part of it. Vichy always was and remains nul and void. I myself am the President of the Government of the Republic. Why should I have to proclaim it?” (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 772.3, Ch. 8, 77%).

With this, de Gaulle stepped out to the adulation of the crowd which droned out all else. De Gaulle then rendered one of most significant political speeches of his career:

Why should we hide the feelings that fill us all, we men and women who are here in our own city, in Paris that has risen to free itself and that has succeeded in doing so with its own hands? No! Let us not hide this deep and sacred emotion. There are moments that go beyond each of our poor little lives. Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France!

Since the enemy which held Paris has capitulated into our hands, France returns to Paris, to her home. She returns bloody, but quite resolute. She returns there enlightened by the immense lesson, but more certain than ever of her duties and of her rights.

I speak of her duties first, and I will sum them all up by saying that for now it is a matter of the duties of war. The enemy is staggering, but he is not beaten yet. He remains on our soil.

It will not even be enough that we have, with the help of our dear and admirable Allies, chased him from our home for us to consider ourselves satisfied after what has happened. We want to enter his territory as is fitting, as victors.

This is why the French vanguard has entered Paris with guns blazing. This is why the great French army from Italy has landed in the south and is advancing rapidly up the Rhône valley. This is why our brave and dear forces of the interior are going to arm themselves with modern weapons. It is for this revenge, this vengeance and justice, that we will keep fighting until the last day, until the day of total and complete victory.

This duty of war, all the men who are here and all those who hear us in France know that it demands national unity. We, who have lived the greatest hours of our history, we have nothing else to wish than to show ourselves, up to the end, worthy of France. Vive la France!

(Christine Levisse-Touzé, Paris Libéré, Paris Retrouvé, Paris: Découvertes Gallimard, 2003, p. 95)

Not once had the CNR or the resistance been mentioned. If de Gaulle’s failure to announce a new republic had been a disappointment to Bidault, de Gaulle’s lack of acknowledgement of the FFI was a blow to the communist resistance. Before the stunned men in the room had time to process what had happened, de Gaulle was muttering his goodbyes and left. (Collins & Lapierre, 335)

As the crowd roared with approval the CNR knew that their aspiration for political leadership in the postwar national government had been nothing less than a four-year fantasy. Adding to the anguished pain of the CNR were yells of “Vive de Gaulle!” and “Vive la France!” from the crowd outside, which included members of their own resistance. (Yvonne Féron, Délivrance de Paris, 55)

“We’ve been had,” said one of the CNR’s communist secretaries. (Collins & Lapierre, 335)

By now, de Gaulle had further decided to cement his hold on the future government by organizing a massive march down the Champs Élysées on the 26th. Then there was more good news. Eisenhower had recognized him “as de facto French head of state”. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 758.7, Ch. 8, 75%)

However, Washington had a condition: Their recognition was given on the “understanding that it is the intention of the French authorities to afford the French people an opportunity to select a government of their own choice”. (Collins & Lapierre, 335)

As the sun faded away, so did the fighting. The numbers of Parisians in the streets began to multiply. But not all was joy. As Corporal Arthur Kaiser, tank driver of the Sherman Bordelais II (of 4/12th RCA) alighted from his tank, he was confronted by a middle-aged woman.

The woman introduced herself as the mother of the Zagrodski brothers. She had been drawn to the Bordelais by the name. The original Bordelais had been commanded by her older son, Lt Michel Zagrodski. No one had told her that Michel had been killed in action on 10 August and that her younger son, Jean, had also followed him into death less than 24 hours ago. Unable to tell Madame Zagrodski the news, Kaiser directed her to an officer nearby. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, Loc. 667.4, Ch. 10, 63%)

As night came, the 2e DB’s command post was moved from the Gare Montparnasse to the Latour-Maubourg barracks, northwest of les Invalides. With nightfall, calm largely returned to the capital. The Allied units set up their bivouacs to the singing and the cheers of the population ringing in their ears.

The revelry was also punctuated by thousands of sexual acts that night. Possibly more than a few were acts of sexual violence but Suzanne Massu, a member of FFI later said that: “Many Parisian women were too charitable to let our lads spend their first night in the capital alone.” Ernie Pyle was more ribald: “Any [GI] who does not sleep with a woman tonight is just a sissy,” he apparently told a fellow war correspondent. (Nieberg, Loc. 499.1, Ch. 9, 82%)

Meanwhile at the Ministry of War, Leclerc arrived with sobering statistics – the daily casualty list. In fighting that day, the division had lost 28 officers and 600 other ranks killed or wounded. Leclerc added that the division had killed some 3,200 Germans so far – not counting over 1,000 killed by “partisans” in the preceding days. (De Gaulle, loc. 664, Section 308-309, 44%).

The end result of all this sacrifice was that the French had “narrowly avoided a new Paris Commune!” in the words of Pierre Koenig. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 776.8, Ch. 8, 77%)

But perhaps the best words about the day of liberation were assembled by Camus, writing in Combat. “Those who never despaired of themselves or their country can find tonight under this sky their recompense.” (Albert Camus, Actuelles: Chroniques, 1944–1948 (Paris: Gallimard, 1950), 23)

TWILIGHT

By dawn on the following day of a renewed Paris, de Gaulle was assembling the final pieces of his plan to cement his assent as France’s new leader.

At the heart of his plan for the day was a massive victory parade by the 2e DB spanning three miles from the Arc de Triomphe to the cathedral of Notre Dame. The symbolic parade would solidify his base of power and assure the populace that law and order would be restored, as opposed to a communist takeover.

News of the parade began to spread like wildfire, fed by resistance radio and word of mouth. Thousands of ordinary Parisiens began to filter into the city to see the show. Even the communist party’s L’Humanité newspaper was unable to resist being caught up in the euphoria. Its front page for 26 August 1944 read: At 15:00, from the Arc de Triomphe to Notre Dame, the people will unanimously acclaim general de Gaulle. (https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-jean-moulin/oeuvres/journal-l-humanite-du-26-aout-1944#infos-principales)

Leclerc had informed de Gaulle the previous night that the Germans were still in strength in the north of the city. “At Saint-Denis, in La Villette, [German] elements refused to lay down their arms, alleging that they were not under von Choltitz’s orders,” de Gaulle wrote later. “Part of the German 47th Division is moving into Le Bourget and Montmorency, presumably to cover retreating columns further north.” (de Gaulle, loc. 644, Section 309, 44%)

On the morning of the 36th. Leclerc dispatched a light combat detachment under Major Roumianzoff to the northern section of the city, to Aubervilliers-Saint Denis area while he prepared the rest of his division to participate in the parade. He traded his battledress for a formal Khaki tunic while continuing to wear his British battledress pants and canvas gaiters.

Gerow was aghast to learn about the parade. In his mind, the 2e DB should have maintained pressure against the Germans retreating to the north. Although von Choltitz’s command had been smashed, some 3,000 German troops remained unaccounted for and the Luftwaffe airfield at Le Bourget still held several combat aircraft. (Neiberg, loc. 504.4, Ch, 10, 83%) As it was, some 2,600 German troops emerged from the Bois de Boulogne in the afternoon with their hands up. Had they decided to attack during the parade, chaos would have ensued. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 621)

All that prevented the Germans from counter attacking from the north towards the center of Paris was Roumianzoff’s mixed bag of Spahis and the 12th US Army Regiment which had not been invited to the parade. De Gaulle’s political machinations could only conceive a complete French triumph.

Installed at Marshal Pétain’s old office at Les Invalides, the frustrated Gerow dispatched an American liaison officer at 10 am with orders for Leclerc to rejoin the rest of V Corps on the frontline. The orders did not mince words:

You are operating under my direct command and will not accept orders from any other source. I understand you have been directed by General de Gaulle to parade your troops this afternoon at 1400 hours. You will disregard those orders and continue on the present mission assigned you of clearing up all resistance in Paris and environs within your zone of action.

(Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 620)

Leclerc, however, sent a staff officer, Major Weil, to inform Gerow that the division would carry through the parade.

According to Blumenson, some of Leclerc’s staff were “furious” at being pulled from combat operations for a public relations exercise such as a parade. “But [they] say Leclerc has been given orders and nothing they can do about [it].” The staff officers reportedly added the parade would tangle the 2e DB so completely that it would be useless for operations for at least 24 hours. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 620)

Gerow retorted that Leclerc’s refusal to obey constituted a court martial offense under the laws of the US Army. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, Loc. 668.3, Ch. 10, 65%). Gerow had some reason to feel ownership of the division. To allow the Free French to form an army, the United States had provided de Gaulle with 3.25 million tons of equipment and almost 50.2 million small arms. (Blumenson, Liberation, 133)

Leclerc and his staff were dining with de Gaulle at the Restaurant Chauland at the corner of Les Invalides and the Rue de l’Université when the US liaison officer appeared with the reiteration of Gerow’s original orders.

Leclerc is said to have told the liaison officer: “Precisely because these orders were given by idiots, means I don’t have to carry them out!”

To cool tempers, De Gaulle intervened, saying: “I lent you General Leclerc. Surely I can take him back for a little while.” (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 668.3, ch 10, 65%) De Gaulle also tried to satiate his Allies by inviting Gerow and his staff, plus one US Army officer and 20 troops to join the parade. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 618). A similar number of British army personnel were also invited.

Despite de Gaulle’s proclamations of a wholly French triumph, the unit which stood on parade at the Place d’Etoile was Captain Dronne’s 9th Company of Franco-Spaniards.

As de Gaulle reviewed the company, he appeared slightly discomfited in photographs of the event. What must he have thought of the halftracks with their Spanish names, manned by sun-tanned internationals? He was likely reminded that this very French triumph had been enabled by foreigners wearing the uniform of the 2e DB such as the Spanish but also Cubans, Chileans, Armenians, Italians, Mexicans, Argentines, Americans from the continental United States and Puerto Rico, Uruguayans and even anti-Nazi Germans.

De Gaulle saluted the company in recognition of their feat in entering the city first before all else. (Mesquida, loc. 2482, 52%). The company halftracks stood among 50 parked in a line across the width of the place de l’Etoile, facing down the Champs-Elysées. The tanks of Langlade’s Tactical Group were lined down the Champs Élysées.

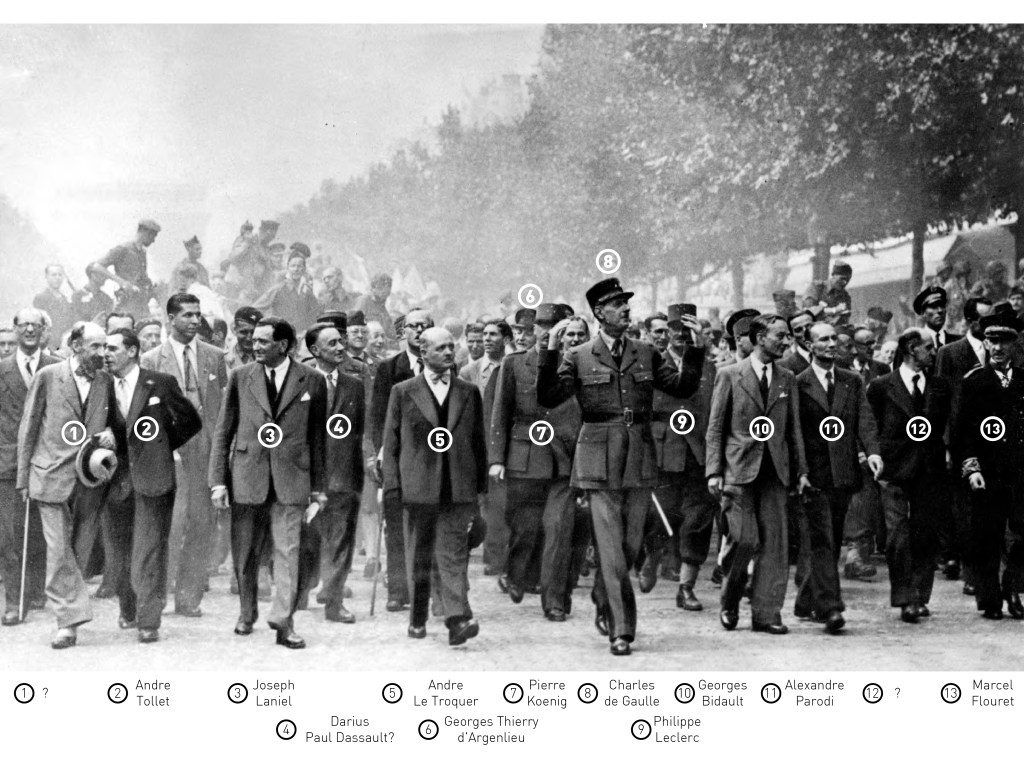

De Gaulle went to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and flanked by the division’s Moroccan troops with their distinctive red fezzes, he laid a wreath of pink gladioli wrapped in a tricolor ribbon upon the tomb. (Cobb, 320) With the crowd blaring and cameras flashing de Gaulle and his entourage which include Rol-Tanguy, Parodi, Luizet, Bidault, Flouret, Le Troquer, Leclerc, Juin, Bloch-Dassault, Admiral Thierry d’Argenlieu, Leclerc, General Koenig and members of COMAC and CPL (de Vogüé, Kriegel-Valrimont, Andre Tollet and Hamon) started down the Champs-Elysées.

To the general Parisian crowd, most of the top brass of the resistance were strangers. As the historian Mathew Cobb wrote, “Most of these names and faces are now forgotten, and even at the time, few of them were known to the public”. (Cobb, ibid) When the crowd cheered, it was for the Free French forces and the man who wielded them – de Gaulle.

The group marched with four Stuarts of Captain De Boissue’s protection squadron as vanguard (Lauraguais, Limagne, Limousin, and Verdelon). Four halftracks of the 9th Company (Guernica, Teruel, Resistance and Guadalajara) and four Shermans brought up the rear. (Mesquida, loc. 2482, 52%)

The Spanish halftracks flew a small Spanish Republican tricolor of red-yellow-purple. (Mesquida, loc. 2482, 52%) One Spaniard, Corporal Pablo Moraga Díaz, a Libertarian from Ciudad Real was photographed making the clasped hands, Libertarian and “Unios Hermanos Proletarios” salute from the halftrack Teruel. Five months later, on 26 January 1945, Moraga Diaz was dead. Like so many others in the 2e DB who participated in the liberation, Moraga Diaz had not lived to see the end of the war.

For de Gaulle, meanwhile, the incarnation of a Paris in celebration was “like a dream come true.” (De Gaulle, loc. 649.1, Section 312, 45%)

I rekindle the [eternal] flame. Since June 14, 1940, no one had been able to do so except in the presence of the invader. Then, I leave the vault and the platform. The assistants step aside. In front of me, the Champs-Elysées! Ah! It’s the sea! A huge crowd is massed on both sides of the roadway. Maybe two million souls. The roofs are also black with people. At all the windows are piled up compact groups, pell-mell with flags. Human clusters are hung on ladders, masts, lamp posts. As far as my eyes can see, it’s only a living swell, in the sun, under the tricolor. (Ibid.)

Standing on a truck on the avenue de Marigny, Micheline Bood was completely swept up in the adoration of de Gaulle. With his existing tallness aggravated by a Kepi, de Gaulle towered above the people in his entourage. “I can understand that people become fanatical about him, that you could die for him,” Bood wrote. “He is a superman. The crowd was literally going crazy.” (Cobb, 322)

At the statue of Georges Clemenceau, de Gaulle paused and saluted.

“What a triumph,” said Bidault.

“Yes, but what a crowd,” de Gaulle replied. (Smith, loc. 338.4, Ch 10, 77%)

The adulation of the crowd was, for de Gaulle, a “miracle” of the national conscience, a gesture of nationhood that illuminated France’s history. (De Gaulle, loc. 649.1, Section 312, 45%)

When de Gaulle reached the Place de la Concorde, he went towards a black Hotchkiss convertible which was waiting to take him to Notre Dame. At about this time, Captain Dronne’s unit was relieved of its security duties by a relay team under Colonel Achille Antoine Peretti, a policeman on de Gaulle’s headquarters staff, who was in-charge of security. No sooner had de Gaulle left when enemy snipers opened fire at the crowd in the Plaza. The gunshots appeared to come from the Hôtel Crillon. The crowd scattered and went to ground.

“It was in front of us, stretching along the Rue de Rivoli, reaching the Place de la Concorde and up the Champs Élysées,” Dronne wrote. “Gunshots seemed to be coming from everywhere. Panic-stricken people were running in all directions, falling in the gutters, lying down in dried-out fountains, huddling behind trees, flower-troughs and even behind our vehicles.” (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 799.2, Ch. 8, 79%)

The Spanish and the Free French troops opened fire at the Hôtel Crillon and the Ministry of the Navy. All around them, the frightened populace screamed in terror.

A BBC reporter, Robert Dunnet, captured the scene:

…There’s been some shooting broken out from the – one of the buildings – I think it’s in the neighborhood of the Hôtel Crillon, just following the passage of General de Gaulle, and there’s smoke now rising from the building and the people – there’s a great crowd – has broken out …the tanks are firing back… the tanks massed in the square are firing back at the hotel, and I’m standing looking just straight across at it – smoke – smoke rising, and whoever opened up on the crowd from the hotel is …sound of gunfire…It’s rather difficult to place where all the fire is coming from. I certainly can hear bullets going past at the moment – that peculiar whistling noise they make – and still these men with the Red Cross flags stand up on this balustrade, right out in the open, holding up their flags and waving, smiling – ‘People, just take it quite easy, it’s all going to be all right.

(Cobb, 325-326)

One Parisian, Jean Galtier-Boissière, was in the Tuileries when the gunfire broke out. He remembered pandemonium erupting. “We were all lying face-down on the grass. Women were shaking with fright, children were crying. I got up and could clearly see machine-gun fire coming from three windows of the Pavilion de Marsan [the north-west corner of the Louvre], sweeping across the Rue de Rivoli and the terrace of the Tuileries.” (Cobb, 325)

When de Gaulle entered the Notre-Dame cathedral, there was another burst of gunfire from unknown assailants shooting from the roof of the cathedral. Bullets ricocheted off the walls. To the admiration of all those who witnessed the scene, de Gaulle remained standing as many others fell flat to the ground. Three members of the congregation were hit and one person died. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 808.1, Ch. 8, 80%)

De Gaulle eventually cut short the service and returned to the Ministry of War. The gunmen were never found. De Gaulle believed a radical faction of the resistance was behind the shooting. But perhaps it was the Milice Française. Despite these hiccups, de Gaulle had cemented his stature as the leader of France. An American journalist said that, “De Gaulle had France in the palm of his hand.” (Alistaire Horne, Seven Ages of Paris, Loc. 848.7, Ch. 19, 78%)

That night, as Paris continued its 48th hour of revelry, German bombers appeared at 11.15 pm. A previous proposal by Hugo Spreele, commander of Luftflotte 3, to pummel the capital was finally materializing. Some 150 German bombers under the command of General Otto Dessloch, came in waves and unloaded incendiaries over northeastern and central Paris. The working-class neighborhoods in the northeast were badly hit.

At Les Invalides, residence of the military governor of Paris, Leclerc and the new governor, General Koenig were preparing to call it a night. Hearing the explosions, the two men sprinted for a balcony overlooking the front esplanade.

Leclerc watched the bombers do their work with helpless fury, wrenching out the same phrase over and over again: “Les salauds! Les salauds! Les Saluds!” (The swines! The swines!) (Collins & Lapierre, 358)

Because of the celebrations in the city, Allied anti-aircraft units had not been able to deploy in strength – and it showed. Colonel Bruce wrote that the “ack-ack was very feeble”. Instead, rank and file 2e DB troops opened up ineffectively at the bombers with pistols, rifles and machine guns. (Lankford, 177)

There was a little water available to douse the flames in the bomb-hit areas of the city. Some 597 buildings were destroyed, including the Halles aux Vins and the Moulin de Paris. (Horne, Loc. 848.7, Ch. 19, 78%; Smith, loc. 348.2, Ch. 10, 79%). The human cost was more frightful: over 1,000 casualties, comprising: 123 dead and 466 wounded in central Paris (including two US GI), and another 80 dead and 422 wounded in the north and eastern parts of the city. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 821.6, Ch 8, 82%)

De Gaulle was also watching the bombing from the Ministry of War. he sighed and said to an aide, “Eh bien, there you see—the war goes on. The hardest days are ahead. Our work has just begun.” (Horne, loc. 848.7, Ch. 19, 78%)

Earlier that evening, he had drafted a letter to Eisenhower asking for the 2e DB to stay on in Paris. “Although Paris is in the best order possible after all that has happened, it is absolutely necessary to leave a French division here for the time being. Until other big units arrive from the south, I ask you to keep the Leclerc division here.” (De Gaulle to Eisenhower, August 26, 1944, Eisenhower Presidential Library)

Eisenhower agreed, but he also went to meet de Gaulle on 27 August to symbolize the act of the Allied supreme commander paying tribute to the provisional president of France. During the meeting, de Gaulle asked Eisenhower for the loan of two US divisions to strengthen the authority of the Free French government in Paris and preserve law and order. (Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, 358) By now, the German 47th Infantry Division was buttressing the German position north of the city.

De Gaulle’s request for help would allow Eisenhower to act on his desire “to show that the Allies had taken part in the liberation.” (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 622)

“I understood [de Gaulle’s] problem,” Eisenhower wrote, “and while I had no spare units to station temporarily in Paris, I did promise him that two of our divisions, marching to the front, would do so through the main avenues of the city. I suggested that while these divisions were passing through Paris they could proceed in ceremonial formation and invited him to review them… I told him that General Bradley would come back to the city and stand with him on the reviewing platform to symbolize Allied unity.” (Eisenhower, 358-359)

The US 28th Infantry and the US 5th Armored Division (massing at Versailles) were selected for the parade down the Champs-Élysées. The march, on 29 August, was more a tactical maneuver than a parade. The parade would allow these two divisions to quickly traverse through the city (without getting bogged up in traffic) and deliver them to the frontline east of the city.

“Because this ceremonial march coincided exactly with the local battle plan it became possibly the only instance in history of troops marching in parade through the capital of a great country to participate in pitched battle the same day,” Eisenhower said. (Eisenhower, 359)

With this, the battle of Paris was over. Afterwards de Gaulle would express regret that the liberation of Paris would only be remembered for the celebrations and not the human cost which went into the endeavor.

On the evening of 25 August, De Gaulle was also told by Professor Pasteur Vallery-Radot who had taken charge of the health services that the FFI had lost 2,500 resistants killed or wounded from 19 to 25 August and that more than 1,000 civilians had been killed during this period. (De Gaulle, loc. 664, Section 308-309, 44%; contradicting figures for the 11 days of the insurrection state that the FFI lost 532 killed and 1,005 wounded. The civilian populace is said to have suffered 283 killed and 687 wounded)

In return, Rol-Tanguy reported on 8 September that FFI had destroyed or captured 35 tanks, 22 guns, 32 MGs, 75 automatic weapons. Over 4,000 summary executions of collaborators by the resistance in the weeks also followed the liberation.

The losses of the 2e DB are more complicated to assemble. According to Philippe de Gaulle, the division lost more troops liberating the capital than it did in the battle for Normandy. “Effectively speaking we lost 97 killed and two 283 wounded out of a complement of twelve thousand men actually inside the old boundaries of Paris alone, and twice as many in the surrounding area, making at least 14% of our strength out of action over eight days,” Philippe wrote. (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 699.3, Ch. 10, 66%)

However, according to the Maréchal Leclerc de Hautecloque foundation, total divisional casualties during operations to liberate the city comprised 145 killed, 172 wounded, 48 tanks and four guns destroyed.

The Germans had suffered 3,200 killed, plus 12,600 troops were taken prisoner (de Gaulle quoted a higher figure of 14,800 POWs). Choltitz’s forces also lost 74 tanks and 64 guns. (de Gaulle & https://www.2edb-leclerc.fr/la-2eme-db/)

If the Normandy campaign had shown Allied feats of arms, the liberation of Paris revealed that even an untested but motivated army such as the Free French could win against superior enemy forces if the will could be summoned. The seizure of the city also allowed the French to reclaim what had been lost – their pride – and restored their political ascendency over their homeland.

As much as Allied High Command had been hesitant to go to the capital in the early days of August, the liberation of Paris provided critical lessons about city and street combat. It also allowed the Allies to compound Hitler’s misfortunates following the defeat of the German army in Normandy. Beyond these military aspects, and in the words of Ernie Pyle, the liberation was also one of the the “loveliest, brightest”‘ stories of World War II. ■

THE ONLY COVERAGE OF BATTLE OF PARIS WITH CLEAR AND CRYSTAL MAPS SO FAR !!!

Very informative for someone such as myself who is only just beginning to trawl through the stories of the Liberation and the participants

Thanks! I’m glad it has been of help.

This is a fantastic site. Thank you for developing it. I would love to connect with you for a project I am working on. I am eager to learn of the sources for the US liason officer who showed up. I beleive he may be the one about whom I am writing but am trying to pin down his name to confirm. Thank you in advance for your consideration.

Thank you. Greatly appreciated! I will get back to you about the liason officer.