SEIZING THE MAJESTIC

De Langlade had arrived at the Arc de Triomphe to find Massu had deployed his tanks facing down each of the major roads and avenues which radiated outwards from the monument like spokes on a wheel.

As de Langlade set his forward headquarters next to the monument, his attention focused on the Avenue Kléber where stood the Hôtel Majestic – the headquarters of the Militärbefehlshaber-i-Frankreich (German military high command in France).

Officially in command was Luftwaffe General Karl Kitzinger who had replaced Stülpnagel from 17 August. Arrested and tried for treason for his role in the bomb plot against Hitler, Stülpnagel was to be sentenced to death by the Volksgerichtshof on 30 August 1944. He was to be hanged the same day at the Berlin-Plötzensee prison.

The many services of the German administration had been installed at the Hôtel Majestic during the occupation. The building had a large assembly of German staff officers, administrative members and even civilians. (http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/ media4505-Officiers-allemands-du-Majestic) However, Kitzinger was not present. Like so many other senior commanders, such as General Karl Oberg, head of the SS in the city and Pierre Laval (the Vichy prime minister), he had fled the city.

Massu sent the 5th Company (RMT) under Lt. Lucien Berne to seize the hotel. Two of Massu’s tanks (Sherman No 50, Flandres II) and an M10, the Mistral, fired volley after volley down the avenue, exploding three German tanks and several vehicles positioned outside the hotel. A Free French infantry bazooka unit ambushed and wiped out a Panzerjäger tank by the Avenue d’Iéna.

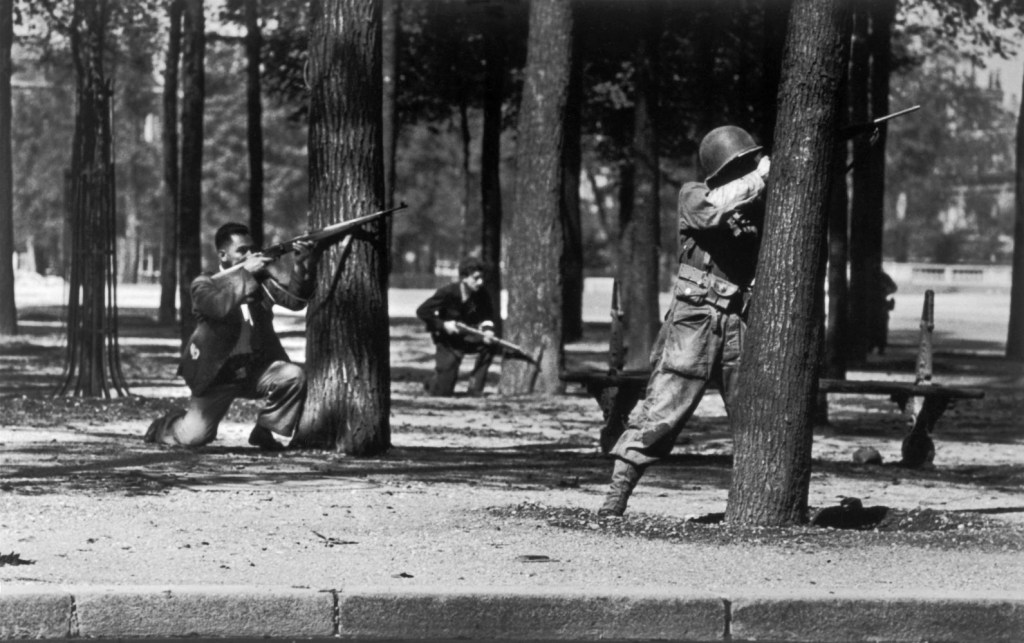

FFI forces tipped-off the Free French about German dispositions around the hotel. The Germans had built a massive bunker on the Rue de la Perouse. (https://liberation-de-paris.gilles-primout.fr/la-reddition-de-lhotel-majestic) As the men of the 5th RMT approached the eastern side of the hotel, the troops in the German bunker opened fire.

A thick smoke filled the sky. A bareheaded, balding German officer appeared, waving a white flag. The German officer told de Langlade that the units around the Majestic would surrender under certain conditions.

Langlade replied that the Germans either surrender within 30 minutes or face annihilation. The officer returned to the Majestic, accompanied by Colonel Massu, a number of soldiers and even a film crew. As the group crossed the rue de la Perouse, a shot rang out. A German sniper had killed Sergeant-Chief Rene Dannic, 38.

Despite this, the Massu and the Free French contingent proceed into the Hôtel Majestic, only to come face-to face with several armed Germans in the east foyer.

“Heraus!” (Get out of here!), Massu yelled.

The Germans began to grumble. “Heraus! Schnell!” Massu shouted angrily.

This cowed the Germans. Some 350 German troops, including two colonels and fifty officers, filtered out of the Majestic and the bunker with their hands up.

Meanwhile, Lt. André Sorret of the RMT reported that 24 Avenue Kléber, which was an insurance company called L’Abeille, was packed with Waffen-SS. Massu dispatched Lt. Berne’s platoon once again to investigate.

Berne entered L’Abeille’s main hallway with a white flag and found the barrel of an MP40 submachine gun pressed against his chest.

“I am a regular army officer,” Berne said. “I would like to speak to your commander.”

An SS major approached.

“All resistance is futile,” said Berne. “In any case, you have one minute to surrender. Don’t waste time. I am giving you one minute. After that, I will attack.”

For a moment the SS men appeared truculent. Then their commander surrendered his pistol. Carrying a load of weapons, Berne led 150 Waffen SS out of the building.

“You look like a Mexican pistolero,” Lt. Sorret joked. (Bergot, 151)

Large crowds of hostile Parisians gathered around the prisoner column. Free French troops had to prevent a woman from gouging the eyes of a German officer with a knitting needle. All captives were on edge. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 745.5, Ch. 7, 74%)

As the Hôtel Majestic prisoners were led away towards the Arc de Triomphe, one of the Germans threw an incendiary grenade. In a flash, a French soldier, Master Corporal Néri, was ablaze. Major Mirambeau who was supervising the prisoners was also wounded. (Cobb, 293) Néri was so badly burned in one arm that it was amputated. (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 745.5, Ch. 7, 74%)

A similar incident occurred when the prison group was marched to the Place de l’Étoile.

Infantryman Jacques Desbordes was crouched behind a tree at the end of the avenue de Wagram when the group of prisoners marched around the Arc de Triomphe, escorted by 2e DB soldiers, including Colonel de Langlade.

He remembered “an opaque cloud enveloping the column.” A machine gun opened fire into the gray-white cloud. Desbordes joined in without realizing it: “To my surprise, the sharp recoil of my rifle told me that I was firing – I couldn’t hear my shots because of the amazing racket. Slowly, the smoke cleared, the machine gun stopped firing and I got up… The machine gunner crawled forwards on my right to see what had happened. I’ll never forget his words, spoken with an accent from Bab el-Oued in Algiers: ‘Bummer. What a mess’.” (Issue 103, 1939-45 Magazine, January 1995)

Seven dead German soldiers lay in a bloody tangle. Somehow de Langlade and the other French soldiers had survived the shooting unscathed. Desbordes believed that the incident was caused by a phosphorus grenade going off by accident.

A protestant priest, Marc Boegner, would witness a third killing near the Arc de Triomphe later that evening. Watching from his apartment window, Boegner saw “four soldiers, barefoot, their tunics unbuttoned, their hands behind their heads.”

The men were taken to the “middle of the place, facing down the Champs-Elysées. People scurry around, photographing them. Then something terrible happens! Because one of them had killed a French officer when they had said they were surrendering, they are all shot dead, straight away, on the corner of the avenue de Wagram.”

It was said that the four men were “Georgians”’ who had been firing on the crowd from surrounding rooftops and had killed a woman and a child. (Cobb, 293-294)

Despite the blood and gore around them, a crowd thronged the tanks at the Arc. Among them was Micheline Bood, the colors of her clothes and ribbons in her hair reflecting the colors of the French tricolors. “It’s crazy: little girls, young women, young people climbed onto the tanks, even dogs wearing tricolor bows,” she wrote. “The cheeks of the French soldiers are covered in lipstick; the men are magnificent, bronzed and burnished by the sun.” (Cobb, 297) Seeing the scenes, Bood considered that perhaps the soldiers were becoming weary of kissing.

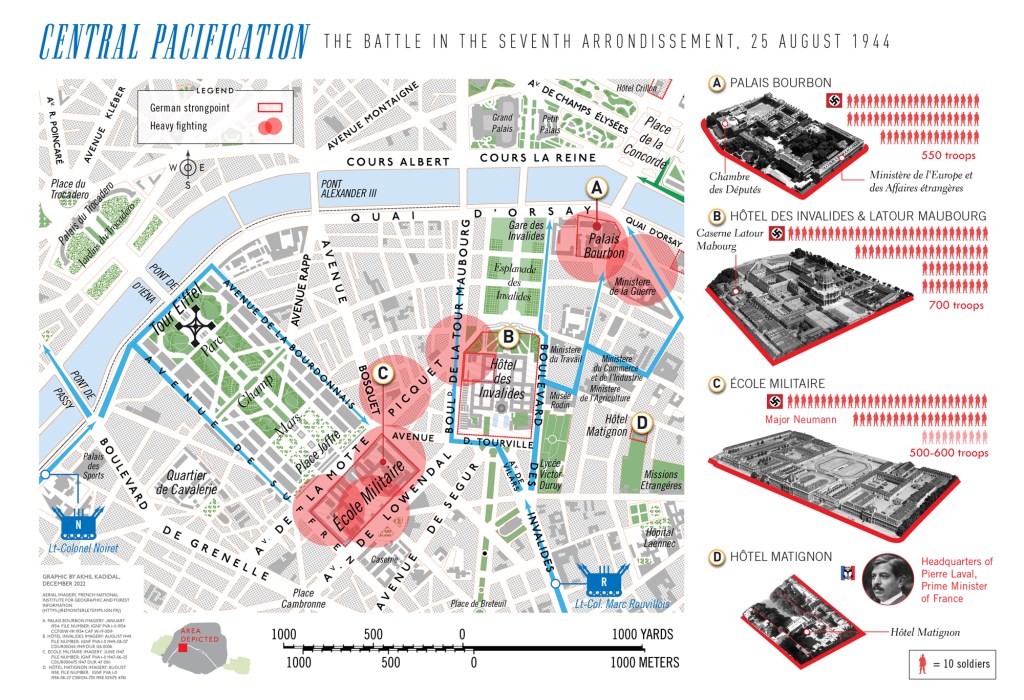

CLEARING THE HOLDOUTS

Even as the German holdouts at the Hôtel Meurice fell, the detachment of French infantry under Captain Marcel Sanmarcelli (3rd Company, RMT), approached the Garnier opera house. At the corner of the Rue del 4 September and Rue de la Opera was the German “Kommandantur” – offices which housed the major part of the German administration of Paris.

A 17-year-old French Jewish girl, Rachel Spreiregen (who had survived the holocaust thanks to forged papers) happened to be walking near the building when the Free French troops pulled up.

The French infantry, with 57mm towed anti-tank guns, blasted German vehicles in front of the majestic opera house. Photographs of the engagement show a column of Free French halftracks on the road with a destroyed German vehicle spewing black smoke in front of the opera house.

Writing in the Washington Post 60 years later, Spreiregen remembered: “Then, it happened,” she wrote. “The surrender of the German command.” German troops and junior officers spilled out of the Kommandantur with their hands up. It was around 2.45 pm.

The previously deserted streets began to fill with Parisians. Lt. Bachy, commander of the 2nd Platoon (3rd Company, RMT) recalled: “All of a sudden there were over a thousand people there – I don’t know where they came from – surrounding each soldier, joyously celebrating our presence, such that the Section Leader could not gather his men together, or indeed give any order at all.” (Fournier & Aymard Vol 2, 36)

“The crowd…spontaneously burst into La Marseillaise, while German officers, hatless, hands in the air, marched down Avenue de l’Opera. The nightmare was over,” Spreiregen said.

“I was awed at the magnitude of the event I was witnessing,” she added. “The German war machine was not invincible after all, and for me, it was the men of D-Day who had driven the point home. It was to them that I owed my freedom and my life.” (August in Paris, 1944 https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2004/08/25/august-in-paris-1944/9bf9210a-f86b-4e50-8017-9944801e7ef3/ (accessed 22 January 2023))

The German prisoners were marched to the Mairie of the 9th arrondissement, which had been turned into a makeshift goal.

The fighting continued to rage at the Place de la Concorde. German forces at the Hôtel Crillon and the Hôtel de la Marine were sustaining heavy fire at French infantry and tanks gathering on the plaza. A German panzerschreck squad launched shells at the tanks.

From inside the Crillon, a German soldier, Quartermaster Wallraf, observed an Allied tank trying to cross the plaza. “A group of foot soldiers followed it, covered by the tank. From the fourth floor, our machine gun fired at the group of infantrymen; the men rapidly turned back, but one of them leapt into the air and fell on his back onto the floor, where he remained, immobile. His comrades came to get him.” (Cobb, 297)

The French Shermans and M10s rotated their turrets looking for the source of the German fire. Several French officers believed that fifth columnists were responsible.

A French voice came over the tank radio: “Watch out, guys… the Fifth Column!”

On cue, a Sherman, the Barrois, fired a shell at the fifth of the Crillon’s decorated columns. The column crumbled and crashed into German vehicles parked below.

“Green to all Greens!” Lt. Nouveau shouted on the radio. “Who the hell did that…?”

“It’s me, Green Four,” replied the commander of the Perthois, Brigadier Sole. “I was told ‘the fifth column’… I don’t know, I’m not from here.” (Bergot, loc. 305, Ch. 16) (Note: In the French Army, the cavalry rank of brigadier is a equivalent to an infantry corporal)

A US journalist described the scene on the radio: “From where I am speaking to you I can hear the explosions of shells and the spatter of machine guns: Boche machine guns, machine guns of the regular army, and the machine guns of the FFI. The Germans set fire to the Navy Ministry and the Hôtel Crillon and the sky is ablaze in the direction of Neuilly and Vincennes. These are the last jerks of the beast receiving the mortal blow.” (Cobb, 297)

Some of the smoke originated from the fighting at the École Militaire. For four hours, the Free French had been inching towards the building from the Champs de Mars while under fire. Reinforced by Shermans from the 12th Cuirassiers, the Free French infantry mounted their final assault along three prongs. One German, Sgt. Bernard Blache, 24, a Berliner, watched from the first floor of the École Militaire and counted at least 17 Shermans. (Collins & Lapierre, 323)

Among the Shermans was the Verdun, commanded by Captain Georges Gaudet of the 4th Platoon (12e RC). The Platoon had a nickname: “The White Elephants.”

Gaudet’s tank roared towards the western gate of the building. Here, an 88mm gun was holding court. The Sherman crashed into the gun and over a barricade amid a shower of debris. Nearby, RMT infantry hurled grenade after grenade into the northern corner of the building. Affecting a breach, the Free French infantry poured inside the compound, accompanied by FFI militiamen. (Cobb, 302) Blache threw his gun away and bolted for the basement. (Collins & Lapierre, 323)

A platoon of Free French sappers under Lt. Borrewater, supported by Gaudet’s Shermans, blew the main door of the building off its hinges. They entered the courtyard to a reception of gunfire. Some of the French sappers entered the building by climbing through windows on the first floor. They began to flush Germans in the upper levels down below where the RMT infantry were sweeping in from the north.

Gunfire and grenade blasts and close-quarters knife fights began to mitigate the German appetite for fighting. At least 50 Germans in the garrison had died. It appears many were gunned down in cold blood by the FFI after their capture. Blache, who was taken captive by the FFI, was horrified to see half a dozen German soldiers killed on the pavement outside. When his guard was distracted, Blache ran from the room – and straight into the arms of Free French troops. He felt relief wash over him.

Some 200 Germans and milice had been captured. Colonel Noiret radioed Leclerc: “We have taken all our objectives.” (Cobb, 303 and Bergot, loc. 282.2, Ch. 15, 43%)

At around the same time, Captain Dronne’s missing 1st Platoon (under the injured Lt. Montoya) was in action against German forces around the nearby Hotel des Invalides. A unit member, 2C Luis Royo-Ibanez, driver of the halftrack “Madrid” recalled decades later that the platoon had entered the city from the Porte d’Orleans.

“We were guided by the FFI because we had no plan and did not know the route,” Royo-Ibanez said. “Our primary objective was the École Militaire. There we were greeted by heavy fire from the houses surrounding Les Invalides. It was not the Germans but the French militia. Once [the École Militaire] pocket was eliminated, we received the order to join the Hôtel de Ville, still in the company of the FFI. There were a lot of people. The halftrack Madrid took [up] position in front of the central gate. Imagine our joy and our pride.”

A group of Spanish troops is said to have entered the Spanish Embassy to hoist the Republican flag there. Despite their gaiety, one incident shocked the Spanish. They saw a French mob viciously shaving the heads of women. For the battle-hardened Spaniards this triggered memories of what Francoist troops had done in Spain during the civil war.

This scene appeared similar to what was witnessed by a German soldier, Lance Corporal Paul Seidel at the Place du Chatelet, after his capture. Seidel saw a line of about 20 French girls, with their heads shaved. They were naked to their waists and a swastika had been painted on each breast. Slogan boards reading, “I whored with the boches,” hung around their necks. (Collins & Lapierre, 325)

The Spanish halted and angrily dispersed the mob. “Do you want to fight?” The Spanish soldiers yelled at the French mob. “Take up arms, go to the front, fight the Germans. Leave these women alone.”

The mob dispersed but to the disgust of the Spanish, they observed some of the mob resume their activities further away. “We asked our officers to inform Leclerc,” Royo-Ibanez remembered. (https://www.anori.fr/les-traditions/infanterie/linfanterie-et-son-histoire/regiment-de-marche-du-tchad-historique-de-la-nuev)

To Rol-Tanguy’s credit, he tried to stop such incidents. He ordered posters put up in Paris denouncing the practice. He called up his subordinates in the FFI and urged them to reign in their forces and the mob. (Neiberg, loc. 530.2, Conclusion, 87%)

THE LAST GASPS

A row erupted at the Prefecture of Police amid the ongoing discussions of surrender between Choltitz and the French officers. Colonel Tanguy and another resistant, Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont (a COMAC member who had been posted to the prefecture), entered the closed room. (Choltitz, 254) Both men were angry that the FFI and the FTP were not being included in the negotiations.

In Rol-Tanguy’s mind, his participation was instrumental. After all, wasn’t it his FFI which had initiated the uprising in Paris and had fought the Germans for the last six days?

Leclerc was annoyed. He replied that the surrender document only concerned agreements between soldiers. However, Rol-Tanguy insisted on being present. Luizet suggested that Rol-Tanguy stay on, to bring the FFI into the ceasefire. An exasperated Leclerc relented. (Collins & Lapierre, 313)

To Choltitz, Leclerc demanded that all German strongpoints be ordered to surrender. As the translator began to read the terms of surrender a second time, Kriegel-Valrimont demanded that Rol-Tanguy also be allowed to sign the surrender document. Leclerc was not politically minded and this suggestion, to him, was bemusing. (Collins & Lapierre, ibid. and Cobb, 300)

He responded that he was signing the document as “Commander of the French Forces in Paris.” He, therefore, represented Rol-Tanguy. Two copies of the surrender documents were quickly signed by Lecerc and von Choltitz. The German general kept one copy. The initial stage of the surrender had ended.

Choltitz was then driven to Leclerc’s headquarters at the Gare Montparnasse. The objective was to finalize the surrender in the presence of de Gaulle whose imminent arrival was expected. At the head of the wheel was Kriegel-Valrimont, to whom Leclerc had given the honor. Kriegel-Valrimont later remembered that drive as “the greatest moment of my life.” (Philippe Raguneau and Eddy Florentin, eds., Paris Libéré: Ils Étaient Là! (Paris: France-Empire, 1994), 100)

Driving past the joyful mass of Parisians, the group entered the train station which in contrast, was quiet and nearly deserted. The only other human presence at the station were US Army and French staff personnel plus railway personnel. (Cobb, 300) It is unclear if Gerow and Barton were at the station at this time.

Upon arrival at about 4 pm, von Choltitz, who had heart problems, suffered a mild heart attack. He rushed towards a small toilet stall and asked for water so that he could take his medication. Leclerc’s adjunct, Major Weil, gave him a glass of water and said, “General, I hope you don’t mean to take poison.”

Choltitz replied, “No, young man. We won’t do that.” (von Choltitz, 95)

After he had taken his medicine, von Choltitz engaged Weil in conversation. He admitted that Germany would lose the war. “If I might give you some advice,” von Choltitz said. “When you meet up with the Russians in Germany, don’t stop, march on to Moscow!” (Moore, Free France’s Lion, loc. 675.2, Ch. 10, 64%)

When von Choltitz had composed himself, he was shown to an office and told to sign a proclamation ordering his strung out command to surrender. A French officer recounted that von Choltitz seemed “completely vacant, as if in a dream…he seemed to be completely stunned by events.” (Cobb, ibid)

At this stage, Kriegel-Valrimont again suggested that Rol-Tanguy should sign the surrender document. This time Chaban-Delmas supported the move. Earlier that day, Leclerc had been astonished by the sight of Chaban-Delmas, only 29 years old, a civil servant before the war and now wearing the uniform of the Free French with the stars of a Brigadier-General. But Chaban-Delmas was one of de Gaulle’s direct representatives in Paris and a man with clout.

Leclerc was swayed by Chaban-Delmas’ opinion about Tanguy. Part of this was because Leclerc appeared not to know how this matter must be tackled. Certainly, he did not want to exacerbate tensions with the FFI. Part of him remained bemused by all these political machinations.

When it was decided to amend Leclerc’s copy of the surrender document, the Free French officers observed that Tanguy audaciously wrote his name at the top of the document before Leclerc’s name.

Another significant element of the surrender document was that document was signed in the name of the French Provisional Government. There was no mention of SHAEF. (Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, 618) This projected the control of Paris as being undertaken by de Gaulle, which also sealed his ascendency as the future head of French government. (Cobb, 300)

Choltitz was then asked to issue an order for his men to stop the fighting. This was needed as scattered German strongpoints (Stützpunkte) continued resistance. “I composed the order which instructed my soldiers to end the purposeless fight,” von Choltitz said.

Order! The resistance in the sectors of the Stützpunkte and within the Stützpunkte must cease immediately. By order of the Commanding General v. Choltitz, General of the Infantry. (von Choltitz, 96)

“I accepted the responsibility for the end of hostilities and wanted to do this with a full conscience,” Choltitz said. “My opinion was that a general when he sees the fight is hopeless does not sacrifice his men unnecessarily. I did not want the bases that were spread throughout the city to continue the fight after their leaders had surrendered.” (von Choltitz, 93) It was about 4.20 pm.

De Gaulle arrived at the train station at around 4.30 pm. His drive into the city had overwhelmed him emotionally. The roads he took into the city were the same he had taken during his exit four years before. (Collins & Lapierre, 327) When he had last left Paris, he had the rank of a Brigadier-General. Now, he was something more, he was a liberator.

In footage of the event, de Gaulle is shown to a table at the end of Track 21 in the train station. (Collins & Lapierre, 327). Grasping the surrender documents, de Gaulle put on his glasses and began to read. Rol-Tanguy, in his Spanish Civil War uniform, appeared uneasy. Meanwhile Chaban-Delmas, stood at attention in front of de Gaulle, waiting for the acknowledgement of his master whom he had never met.

De Gaulle ignored everyone. Abruptly, his face showed annoyance. He called to Leclerc. He demanded to know why Rol-Tanguy had also signed the document.

“Why do you think that I nominated you interim governor of Paris back in Algiers, if not for you to accept von Choltitz’s surrender?” de Gaulle asked Leclerc.

“But Chaban agreed,” replied Leclerc.

“Even so it is not correct,” de Gaulle said. “In this matter you are the higher ranking officer and consequently solely responsible.” (De Gaulle, The Wartime Memories, Vol. 2, Unity 1942-44, 578, & Boissieu, 255–256)

In de Gaulle’s mind, von Choltitz had not surrendered to Rol-Tanguy. Hence, Rol-Tanguy’s appearance in the document was improper. De Gaulle was also aware that a CNR proclamation which hailed the liberation of Paris had pointedly failed to acknowledge the Free French. (Collins & Lapierre, 327)

Leclerc appeared to be bemused again. He shrugged. (Cobb, 302)

De Gaulle composed himself. He took off his glasses, stood up and began to shake the hands of those in the room. Leclerc introduced Chaban-Delmas. “”Sir, do you know General Chaban?”

De Gaulle put a cigarette in his mouth and gaped at Chaban with something resembling contempt. To Chaban-Delmas, it was clear that de Gaulle was stupefied that a young man of 29 who looked about 20, could be a General.

But Chaban-Delmas had lived several lifetimes in his young age. A 2nd Lieutenant in the French Army during the phony war, he could have left France in August 1940 after the collapse but instead he had joined the “Hector intelligence network,” a resistance organization in northern France which was assembling information on the German takeover of French industries. Employed by the Ministry of Industry, Chaban-Delmas was in direct contact with British Intelligence from the end of 1942. By October 1943, he was in the Military Delegation of the GPRF. Seven months later, in May 1944, he had become national military delegate in charge of transmitting the orders of General Koenig in London to the resistance in France and ensuring that they were followed.

He had been promoted to the rank of Brigade-General by de Gaulle’s administration in Algiers on 15 June 1944. Clearly, de Gaulle appeared to have forgotten all this.

“Then the statue moved,” Chaban-Delmas said. “I was given a strong handshake – double strength – while the voice pronounced three words against which all awards and honors paled: ‘C’est bien, Chaban’.” (Cobb, 302)

De Gaulle was next introduced to Rol-Tanguy. In a remarkable show of solidarity, de Gaulle shook Tanguy’s hands warmly and thanked him for having “driven the enemy from our streets, and for having decimated and demoralized his troops, and blockaded his units in their strongholds.” (de Gaulle, Unity 1942-44, loc. 636.4, Pris S05, 44%) He had no desire to antagonize the FFI just yet.

He reinforced his act of goodwill with a statement to a radio journalist on the way out: “The German general commanding the Paris region has surrendered to General Leclerc and the commander of the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur.” (Cobb, 302)

De Gaulle also greeted his son Philippe, an ensign and a platoon commander in the RBFM, who stood among the men. Leclerc had ordered teams of French and German officers to drive through the city jointly announcing the ceasefire. Philippe shortly left for the Palais-Bourbon in the company of a German Major to receive the surrender of the troops in the building.

Choltitz meanwhile, was ushered into a large room where other German prisoners were being held. Junior and mid-level officers appeared gratified to see him. De Gaulle himself left for his old office at the Ministry of War. He arrived at about 5 pm. The office was exactly as he had left it. The building had been unoccupied in the last four years. It was a capsule of time.

“Gigantic events had overturned the world [in 1940],” de Gaulle wrote. “Our Army was annihilated. France had virtually collapsed. But at the Ministry of War, the look of things remained immutable…. The vestibule, the staircase, the arms hanging on the walls—were just as they had been. Here, in person, were the same stewards and ushers. I entered the ‘minister’s office, which M Paul Reynaud and I had left together on the night of June 10, 1940. Not a piece of furniture, not a rug, not a curtain had been disturbed….On the table, the telephone remained in the same place and one sees, registered under the buttons of call, exactly the same names.”

“Later, I will be told that this is the case with the other buildings where the Republic was framed. Nothing is missing except the state. It’s up to me to put it back. I installed my staff at once and got down to work.” (de Gaulle, Unity, loc. 636.4, 44%)

Meanwhile, Colonel Jay and two of von Choltitz’s other senior aides, were handed orders to secure the surrender of the remaining German Stützpunkts. Jay, with a fellow German headquarters officer, Major Kottrup, plus two Free French soldiers and a tank, were dispatched to the place de la République.

Riffaud’s Saint-Just group and Darcourt’s FTP forces had been in sporadic attack against the barracks all day. Aside from the assistance from Dronne’s 9th Company, the resistance had fought alone. Over a dozen resistance fighters, medicos and even civilians passing by had been killed or fatally wounded. (Cobb, 303)

When Jay arrived, a white tea-towel tied to a stick was thrust into his hands. He walked out onto the open square with Major Kottrup. They were allowed into the barracks. To their consternation, they found the local officers unimpressed by von Choltitz’s order. However, when it became clear that the 2e DB would attack barracks en-masse, the German garrison officers surrendered. Some 500 Germans entered captivity. (Cobb, 303)

New started to filter into Leclerc’s headquarters that FFI forces from the 18th arrondissement had also subdued German resistance at the Clignancourt barracks. The resistance fighters had been operating out of the École des Garçons, 18 Rue Sainte-Isaure, near the barracks. But lacking heavy weapons, the resistance was unable to stop over 100 German troops, with two anti-tank guns and other heavy weapons from escaping the barracks in the afternoon. (Cobb, 303, Footnote 24).

The resistance had better luck at the German headquarters in Neuilly. The headquarters comprised two buildings. Pinned down, the Germans were unable to evacuate. This left them exposed to an attack by two groups of tanks and mechanized infantry from the 2e DB that afternoon. By the time one of von Choltitz’s officers appeared with the surrender order, nearly all of the headquarters’ vehicles had been destroyed. Some 800 German prisoners filed out of the headquarters. (Cobb, 303)

Germans at the Hotel Crillon also began to surrender. For Wallraf and the other defenders of the building, it was inconceivable that von Choltitz would have been taken captive. “A general who, only a short time ago, said he would shoot anyone who tried to get out of defending Paris, such a man could not have surrendered at the first shot, leaving others to carry on fighting!” Wallraf said. (Cobb, 298)

At the Ministry of War, de Gaulle was invited by Tanguy and other French communists to the Hôtel de Ville, to proclaim the return of the French Republic and address FFI resistants. De Gaulle had little desire to visit a municipal center. However, Alexandre Parodi insisted that he visit both the Hôtel de Ville and the Prefecture of Police.

“We’ll go tomorrow,” de Gaulle said.

Parodi, however, wanted to go right away and called on Police Chief Luizet for support. At about that time, Billotte arrived to report to de Gaulle that all the German strongpoints had been subjugated. As they talked, the sound of a colossal explosion came from the direction of the Jardin du Luxembourg.

“And you told me it was over,” de Gaulle exclaimed. “Go fast! There’s still a racket that needs sorting out.” (Moore, Paris ‘44, loc. 756.6, Ch. 8, 75%)

Little had Billotte realized that hundreds of German troops were entrenched in the Jardin and its Senate building. The large concentration of German troops in this location posed the last remaining threat to the French reconquest of their capital.

THE BATTLE FOR THE GARDEN

The garden was defended by nearly 700 German troops – with the personnel divided between the Senate building, the École des Mines and the Lycée Montaigne. For heavy weapons support, the Germans had four formidable Panther tanks (three in the gardens themselves and one parked next to the l’Odéon theater. In addition, three Flammenwerferpanzer B2 (B1bis) were deployed in a narrow garden path leading to Rue Rotrou (formerly rue Crébillon)

Three to four pre-war Renault R-35s were also available, in addition to three Panzerkampfwagen 35R (f), one AM Panhard 178, four Sdkfz 10/4.2 cm Flak 38s (two near the main bunker near the Senate building and one in the main courtyard). Lastly, another pre-war FT-17 was deployed in the main courtyard of the Senate building. This last site was well conceived. (Fournier and Eymard, Vol 2, 79). The hopelessly obsolete FT-17 could at least kill any French infantry which breached the inner courtyard.

The first Free French unit to attack the garden had been General Leclerc’s Headquarters Protection Squadron under Captain de Boissieu (later to become de Gaulle’s son-in-law and a General in the post-war French Army).

As the Squadron (comprising one platoon of M3A3 Stuart light tanks from the 501e RCC and two platoons of M8 Scott howitzers) patrolled around Luxembourg that morning, it found itself taking heavy fire while it traversed the Rue Auguste Comte. One tank was hit and its driver (Lafont) wounded.

Undoubtedly, the German fire benefited from the direction of German observers from the 484th Feldgendarme Company sited in the cupola of the Senate Palace. An irate Captain de Boissieu ordered his men to open fire on the Senate palace. The Free French tankers hesitated, agape. To fire on the senate was anathema. But goaded by de Boissieu, they did fire.

Civilians approached de Boissieu to tell him that the Senate building was occupied by between 500 and 600 German troops, many of them SS. The director of the École des Mines added that an underground tunnel connected the École to the Senate building. De Boissieu was also told that the Germans had enough food and munitions in the palace cellars to hold out for several weeks.

The platoon of Stuarts from 501e RCC drove towards the garden. Its commander, Lt. Pierre de la Fouchardière, recalled later that the unit had started the day at around 6 am and had driven through the suburbs to reach the Parisian gateway at 7 am.

“A human tide invaded the roadway, shouting, howling, and climbing the tanks. We had the greatest difficulty in the world to move forward. Bourdan [a platoon member]…wept with emotion. My section [platoon] is first to pass on this route. Arrived at the level of the Observatory.” (Fournier and Eymard, Vol 2, 81)

As his unit traveled up the Avenue de l’Observatoire, the revelers became scarce and then disappeared all together. A niggling concern tugged at La Fouchardière. Being unfamiliar with Paris, he climbed out of his turret to ask an old man, half-hidden in a doorway nearby: ‘Where are the Germans?’”

The old man pointed to some trees and said: “They’re over there.” (Fournier and Eymard, Vol 2, ibid)

La Fouchardière did not know that the trees belonged to the Jardin du Luxembourg. He decided to leave three tanks for observation while he entered a parallel street with a single Stuart. This street, he learned later, was the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Up the road was the École des Mines. The Free French had been told about a bunker on the corner of Rue Auguste Comte and Boulevard Saint-Michel. The FFI had already attacked the bunker – unsuccessfully.

A policeman in uniform joined la Fouchardière’s party. “We were coming near the statue [of] Auguste Comte,” la Fouchardière said later. “Boom! A projectile grazed the tank.”

A German in the bunker, Sgt. Martin Herrholz, had fired a Panzerfaust. The Stuart reversed and raced for cover into the rue de l’Abbe-de-l’Epee. La Fouchardière could see the bunker, at the foot of a large building, and in front of greenhouses. In that fleeting moment, he also observed the École des Mines, the windows lined with sandbags, the muzzles of Germans machine guns sticking out. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 81 and Collins & Lapierre, 291-292)

Getting on the radio, la Fouchardière called up Sgt. Kerbat, the commander of an M5A1 Stuart called the Boncourt. Shell the bunker, la Fouchardière ordered, adding that Kerbat was to rake the bunker openings with machine gunfire in fast, strafing attacks. For the next hour, Sgt. Kerbat did just that. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 81)

Meanwhile, de la Fouchardière rushed to the third floor of an apartment building which overlooked the École des Mines. There, he saw German helmets bobbing over the sandbags in the windows. He pulled his Colt .45 pistol from its holster and opened fire. A two-hour gun battle ensued.

At around 11 am, de la Fouchardière heard the roar of engines. A small force of M8 Scotts under Lt. Philippe Duplay was roaring towards the east gate of the Jardin. De Boissieu had ordered the tanks forward after receiving incredible news from a radio-amateur resistant tuned into the German radio frequency: the Germans in the Jardin were preparing to launch a breakout attack on Leclerc’s headquarters at Montparnasse station.

“There is nothing at the crossroads of Port Royal than the Boncourt [Stuart] tank to stand up to the five or six Panthers spotted by the civilians in the gardens,” de Boissieu wrote in his log book.

He dispatched an immediate warning to Leclerc. A message was carried by a staff officer, Major Lancrenon, commander of the divisional anti-aircraft units. De Boissieu then moved to contain the Germans within the Luxembourg gardens.

“Half of the Duplay platoon was sent towards the Boulevard Saint-Michel, the tank Boncourt is joined by the tank Colin; all these movements deceive the enemy who believes that we are much more numerous than we are,” he said. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 81)

Moments later, a car with the painted colors of the FFI pulled up sharply near de Boissieu’s location. A party of three men alighted from the car. Among them was a man wearing a helmet and five rank stripes on his jacket. He introduced himself to de Boissieu as Colonel Fabien, commander of a battalion of the FTP. This was the so-called 1st Battalion of Eure et Loire – a fanciful title as Fabien had only 300 men ringing the gardens – less than half of the standard strength of a standard battalion. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 81 and http://www.museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media4310-Char-Panther-immobilis-dans-les-jardins-du-Luxembourg)

Before de Boissieu had time to wonder where this battalion was, a group of militia, wearing the armbands of the FTP emerged from the corner of the Rue d’Assas.

Fabien was actually Pierre Georges, a 25-year-old Parisian local. Georges was as flamboyant as he was brave. He had been wounded twice in the Spanish Civil War and once in Czechoslovakia where he had fought with French volunteers against the German occupation of Sudetanland. (Collins and Lapierre, 290). He had taken the nom de guerre of Colonel Fabian and had participated in a series of assassination of Germans in 1943. He was eventually captured and tortured, but escaped.

Since morning, local FTP forces under Fabien had been probing into the gardens only to be thwarted by fierce German fire.

The FTP’s linkup with de Boissieu was as advantageous to de Boissieu as it was to Fabien. Leclerc sent an order to Fabien to appear at his headquarters so that the detachment could be placed under the command of the 2e DB. Although Fabien’s men were poorly armed, Leclerc and de Boissieu saw their value for reconnaissance and as infantry support.

By now, Lt. Duplay and his platoon had arrived in the battlezone. Eager to enter combat, Duplay did not stop to confer with de Boissieu at his command post in the Port-Royal metro station. Instead, the Duplay platoon roared up the Boulevard Saint-Michel, headed for the main gate of the garden. Germans in the École de Mines open fire. One M8 maneuvered to avoid being hit and crashed into a second M8 commanded by Sgt. Tredez. Both tanks became immobilized.

Duplay’s own M8, named Mosquet, was the next to be hit but drove on. The detachment found that the main gate to the garden was chained shut. Two tank crewmen, Fauguet and Arnould attacked the chain with pickaxes as German troops opened up with small-arms fire. When the chain was broken, the detachment entered the garden – only to see a Panther tank.

Almost immediately, one of the M8 Scotts, La Coulverine, was hit by a German projectile. La Coulverine erupted into flames. Duplay’s tank, which was still in the boulevard outside, dashed into a side street to avoid destruction.

Armed with a grenade, Fauguet moved on to destroy the Panther. At about this same time, a US Army cavalry patrol appeared from the Boulevard de Port-Royal. The American GIs offered to help Duplay knock out the Panther. They had a jeep with a bazooka and an M8 Greyhound armored car. (Fournier & Eymad, Vol 2, 82)

During the attack, one of the Americans who carried the bazooka was shot and killed. Fauguet scrambled to pick up the bazooka. At this moment, a bullet smacked through his helmet. He fell, dead. Other Americans, aided by French troops, destroyed the Panther. (Fournier & Eymad, Vol 2, Ibid.)

Meanwhile, Arnould was hit in the chest by a bullet. Although rushed to the resistance-held Cochin hospital nearby, he also perished.

By now, Leclerc had ordered Lt-Colonel Putz to relieve de Boissieu. For the task, Putz had two platoons of tanks (the 2nd and 3rd) from de Witasse’s 2nd Company (501e RCC). This unit had reached the banks of the Seine at around 10 am. Now, it was being turned back south to neutralize the Germans at Luxembourg. Additionally, Putz had the 2nd and 3rd Platoons of the 4th Company of the RMT commanded by Lieutenants Rodel and Lespagnol respectively. Putz also had Captain Maurice Sarrazac’s 10th Company of the RMT.

The Shermans of Captain Noël’s 3rd Squadron of the 12th Regiment de Cuirassiers (RC) were also dispatched to reinforce Putz. Like a beacon, Luxembourg was drawing combatants en masse.

At about 11 am, Putz ordered Captain Sarrazac and Captain de Witass to prevent the German garrison from breaking out into the streets of Paris. Putz was worried because he did not know if the Germans had a reserve of tanks in the Senate building’s Cour d’honneur.

Captain de Witasse’s tank force arrived at the Place Edmond Rostand. The tanks trundled into watch positions, to prevent a breakout by German armor. De Witasse also sent Lt. de la Bourdonnaye’s 3rd Platoon to bypass Place Edmond Rostand via the Rue Soufflot. De la Bourdonnaye’s orders were to emerge east of the Gardens on Boulevard Saint-Michel near the Ecole des Mines.

At the Place de la Sorbonne, however, the Sherman Lützen came under fire from an enemy armored car lurking on the Rue de Vaugirard near the l’Odéon theater. Several FTP and FFI militiamen were injured in the fusillade of fire.

Meanwhile, wanting to locate German positions in the area, Warrant Officer André Corler, 27, the adjutant of the 2nd Company ran up the stairs of an apartment at the corner of the Rue de Médicis. German troops in the blockhouse in the garden observed him take up station behind the half open shutters of a window. They opened fire. Corler was killed. (www.museedelaresistanceenligne.org)

At about the same time, a Panther tank, posted next to the L’Odeon Theater on the Rue de Médicis began to fire at the Shermans congregating at the Place Edmond Ostand.

De Witasse dispatched a Sherman armed with a 105mm gun to destroy this Panther. Commanded by Sgt. Robert Boccardo, a plump, jovial-looking Frenchman, this Sherman, named La Moskowa, moved slowly along the Rue de Vaugirard towards the Panther. De Witasse guided the tank forward on foot.

The crew, which performed heroics during the liberation of the capital was largely killed afterwards. This happened at Hablainville, in the Vosges, on 1 November 1944 when the tank became stuck in the mud. Multiple German anti-tank guns opened fire and struck the vehicle. Fabre was seriously wounded and died of his wounds. De Cherchi was also seriously wounded but lived, although he never returned to combat again. Fleuret was killed as was Sergeant Boccardo. Fleuret‘s heartbroken parents took his body back to their hometown after the war. They bought a plot of land next to their son’s grave and lived next to it. Only Kartner survived the event unscathed.

The Moskowa’s gunner, Corporal Louis de Cherchi, (a tall, strapping young man) remembered that the tank had taken up station in front of the statue of August Comte. He had fired three shells at the senate rotunda when the tank was ordered to engage the Panther.

We “crossed the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince and there I found, in front, the rear of a Panther tank. I fired an explosive to break up his caterpillar [tracks]. Unfortunately, when the smoke cleared, I saw no more of the German tank (being myself hidden by a corner of the wall at the corner of the street of Vaugirard and the rue de Médicis),” he said.

“We were still advancing on the Rue de Vaugirard and there, we found the same tank which turned its turret to hit us. I was faster than him and fired three shells: the first shell hit the underside of the gun mantle, the second on its shielding, the third on the front left. The crew fled, abandoning their tank,” he added.

The German crew ran into the senate building.

Second Lieutenant Jean Lacoste of the 2nd Squadron (2nd Company, 501e RCC) arrived in the battlezone in the tank of his adjutant, Sgt-Chef Journet. Lacoste’s own Sherman, the Friedland, had broken down beyond the village of Haÿ-les-Roses. Lacoste’s orders were to progress up the Boulevard Saint-Michael.

At the intersection of the Boulevard Saint-Germain, he was moved to see French youths working hard to clear a barricade so that the tanks could pass through.

“I learned that several had been killed trying to locate enemy strongpoints in order to inform us. It is that good will alone was not enough to make effective fighters. I was very angry with all the officers who had abandoned their uniforms during the occupation and remained passive,” Lacoste said. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 84)

The barrage of gunfire became a constant din. Free French bullets and shells pockmarked the Senate building facade. Bullets tore apart protective sandbags, producing a dust cloud which concealed the Germans. Civilians in white garb and red cross insignia ran here and there, trying to recover the wounded. One medic, a young woman, was shot and fell. The irate Free French responded by shelling the fortified balcony of the senate.

After de Witasse’s Shermans arrived, Leclerc pulled de Boissieu back. The protection squadron would arrive at Montparnasse station headquarters at around 5 pm. Meanwhile, Captain Noël’s 3/12th RC was driving towards the garden. Noël’s squadron entered Paris at 12.30 pm.

The squadron’s 2nd Platoon, under Lt. Pierre Krebs, had orders to conduct a reconnaissance along the Boulevard Montparnasse, towards the station. The squadron’s 1st Platoon, commanded by Lt. Desforges moved along the Boulevard Port-Royal. Lt. Erik de Colombel’s 3rd Platoon was in reserve. At 2.30 pm, Noël’s units arrived near the garden to the sounds of concerted automatic fire.

Gunfire appeared to be emanating from all major buildings in the area: including the Lycée Montaigne and the School of Pharmacy. Noël was astonished to see the wreck of an M8 Scott (from Duplay’s platoon) on the Boulevard Saint-Michel.

“I decided to send a patrol of two tanks, commanded by 2nd Lt. Colombel, to recognize the outskirts of Luxembourg, while Lieutenant Krebs carried out a reconnaissance on the Rue d’Assas and to demolish a blockhouse [based on FFI intelligence],” Noël said. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 83)

German guns atop the Senate building raked the Colombel patrol. Anti-tank shells struck Colombel’s Sherman, Bourg-le-Roi. A fire erupted on the hull of the tank. Colombel and his crew extinguished the flames but abandoned the tank. A second Sherman, the Clery, commanded by Maréchal des Logis Beaumel, also erupted into flames after a 75mm tracer round fired by a Panther tore along a camouflage netting draped on the Sherman’s rear deck.

Noël reported that the rest of the squadron destroyed three out of four blockhouses and some infantry. Yet, Noël had no idea what had happened to Lt. Colombel.

At 3.30 pm he sent a M4A3(76) Sherman called the Licorne to investigate. Commanded by Aspirant Mandat de Grancey, the Licorne encountered a Panther on the west side of the Senate. The Licorne fired a shell which hit the Panther in the turret. The Germans bailed out. The Licorne continued on and seeing a 75mm anti-tank gun, fired three high-explosive shells in rapid succession to destroy the gun.

Meanwhile, Lt. Krebs’ patrol had liaised with two M10 Wolverine tank destroyers from the RBFM which had appeared from the Rue d’Assas. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 83-84) By 5 pm, Noël was writing that his squadron had knocked out two Panther tanks, one 75mm gun and seven blockhouses.

At around this time, a ceasefire was announced. An unnatural silence befell the area. The tank crew of Sgt. Maurice Carlier’s Lutzen took this opportunity to dump their still burning shell casing the floors of their turret on the street outside. The clanging of the shells on the pavement drew scores of souvenir collectors. Many screamed in pain as the hot casings burned their fingers. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 86-87)

As the ceasefire dragged on with no resolution in sight, Leclerc asked von Choltitz to demand that the Luxembourg garrison surrender. At around 6.30 pm, Oberst (Colonel) Karl Friedrich von Unger, von Choltitz’s Chief of Staff, was dispatched to the Senate building to affect the surrender of the garrison. He was accompanied by the commander of the 2e DB’s artillery forces, Colonel Jean Crepin, and another French officer. Crepin had an M1 carbine slung across his back. The delegation was received with gun muzzles pointed at their faces.

The three men are stunned by the scale of the destruction at the Luxembourg. The gardens were littered with broken vehicles and shattered concrete. The inner Senate courtyard was nearly blackened by damage, and littered with expended ammunition.

The delegation was equally surprised by the recalcitrant nature of the German defenders. The garrison commander, Oberst von Berg, as a Luftwaffe officer, appeared to have little control over the SS in the building. At one stage, several young diehard SS officers threatened to shoot von Berg if he negotiated with the French. But von Berg did negotiate – and for nearly 40 minutes.

From outside, French loudspeakers blared that Allied bombers would pummel the senate building from 7 pm. The Germans agreed to surrender after Crepin declared the defenders would not be considered as prisoners of war if they did not surrender within the hour. (http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org)

Oberst von Berg had an hour before him to deliver the message to all his men scattered in the buildings and in the Gardens. What followed next was a brief but furious barrage of gunfire as the German defenders fired off the remainder of their ammunition.

At about 7.35 pm, some 700 German soldiers began to file out of the Senate. They came out three abreast, their hands over their heads. The surrender appeared to give strength to the fury of the French who, as the hours had grown long, had lost their inclinations for mercy.

The American screenwriter-playwright (and future novelist) Irwin Shaw who was a Sergeant in the Signals Corps, had watched all day as the German officer corps struggled to maintain their poise “in the middle of a city full of voluble, newly liberated citizens, mostly women, who have hated you for four years and who spend half their time kissing [their] conquerors and the other half devising means of breaking through the ranks and taking a swipe at the highest officer in your column.” (Samuel Hynes (ed), Reporting World War II, Part 2, American journalism 1944-1946, 252)

This experience was replicated at the Jardin du Luxembourg. A civilian, Paul Tuffrau, who was on the scene observed a column of 150 German POWs. German officers were singled out for abuse. At the front of a POW column was a tall officer. A mass of French civilians gathered to boo the officer and his men. This soon turned to blows. Tuffrau said that soon after, the column of prisoners were bent over as they endured repeated blows from unrelenting lines of Parisians. (Fournier & Eymard, Vol. 2, 89)

A soldier and postwar photographer, Walter Dreizner, wrote in his diary of how people began to throw water on the captives, and on one occasion, even a bicycle. (Cobb, 305-306). When the columns reached the Rue de Rivoli, the angry mob seemed to swell.

A flood of abuse swept over us. These curses came from so many throats that they numbed our ears. They turned into a battle cry: from all sides the masses pressed against us with calls of ‘Hang them!’, ‘Murderers!’, ‘Band of pigs!’, ‘Band of murderers!’, ‘Thieves!’ and ‘Down with the Huns!’ They hit us, pushed us and spat at us. They were completely out of control. Wild beasts had been unleashed upon us and we were their victims, victims who could not defend themselves and were not even allowed to do so. This meant death, a tortuous death. The Parisians were in their element. In the midst of this unbelievable screeching we were pushed, hit and forced to the Palais Royale opposite the Louvre. The tall iron railings around the Palais offered us some protection. We could breathe. I felt as if I were in a cage, but a cage where the beasts were outside, pushing up against the iron bars.

(Cobb, ibid)

At the Vélodrome d’Hiver, the winter cycling track, which had been turned into a goal, captured Vichy officials were made to run a gauntlet of angry Parisiens.

“You are about to see a band of collaborateurs, of men who sold out to the Boches, of traitors,” a FFI militiaman told the raging crowd. The Vichy officials, which included Taittinger, Sacha Guitry (an actor-playwright-director accused of collaboration), Jérome Carcapino (former Vichy education minister), René Bouffet (the former Prefect of the Seine) and others, were made to alight from the police van in single column so that they could be set upon by the baying mob.

Bouffet was beaten so badly that he would die a few days later. Taittinger escaped serious harm by protecting his head with his hands and running down the line. (Moore, Paris ‘44, Loc. 763.4, Ch 8, 76%)

THE ONLY COVERAGE OF BATTLE OF PARIS WITH CLEAR AND CRYSTAL MAPS SO FAR !!!

Very informative for someone such as myself who is only just beginning to trawl through the stories of the Liberation and the participants

Thanks! I’m glad it has been of help.

This is a fantastic site. Thank you for developing it. I would love to connect with you for a project I am working on. I am eager to learn of the sources for the US liason officer who showed up. I beleive he may be the one about whom I am writing but am trying to pin down his name to confirm. Thank you in advance for your consideration.

Thank you. Greatly appreciated! I will get back to you about the liason officer.