The American fighter pilots of the US 8th Air Force who fought and destroyed the German Luftwaffe have largely been given a bum deal by history. Sure, reams of paper have been written about them but scant have they been portrayed by the celluloid or the digital screen. I started thinking about this post while watching “Masters of Air” (detailed in a separate post) and especially about two ace pilots, John Godfrey and Don Gentile, who are nearly forgotten now, but who played their part (however modest) in the final Allied victory. Their combat careers are the subject of the infographic above and some of the text below.

“The ordinary air fighter

is an extraordinary man and

the extraordinary air fighter

stands as one in a million

among his fellows.”

Theodore Roosevelt

In the skies over World War II Europe, relatively green American fighter pilots met their battle-hardened opponents in the Luftwaffe and the result was an astounding test of arms, driven by small groups of talented survivors and stone-cold killers who earned the right to be called “aces.”

Fighter pilots of WWII were like some type of superhumans who went to war, wielding a battery of heavy machineguns and/or cannons. Not all survived the crucible of combat. In any squadron in World War II, a gifted 30% of pilots roughly accounted for 60% of all squadron kills. Another 15-20% of squadron pilots in a given squadron were so much cannon-fodder.

To be called an “ace” in the western air forces of WWII, one needed to have shot down five aircraft (this basic requirement has continued). The Germans did not recognize the term “ace” but instead used the word “expert” (experte). But if measured by the Allied yardstick, the German Luftwaffe had a monopoly on aces during the war — with over 2,880 of them, out of which 104 pilots racked up an hitherto unprecedented number of aerial kills (over 100 each).

The US had 1,200 aces during the war, but none in Europe scored more 28 aerial victories. No Allied pilot (including the British commonwealth and Soviet) exceeded 62 in the war. But as the European air war showed, Allied and US pilots were no welterweights in comparison to their Luftwaffe counterparts. The disparity in scores boiled down to how many opportunities for combat Allied pilots had, shorter tours of operational duty and different operational procedures.

Having fed on the obsolete aircraft of the French and Polish Air Forces in 1940 and then romping through the largely inept Soviet Air Force from 1941, the Luftwaffe was stunned to discover that American fighter pilots could actually shoot them down in combat.

A typical example was in early 1944, in the sky over Berlin, when two American fighter pilots in the US 8th Air Force began a deadly partnership during a strategic bombing raid on the city.

The day was 8 March, well into a rollicking, all-out air offensive initiated by US VIII Fighter Command in January to destroy the Luftwaffe.

Flying new North American P-51B Mustang fighters, Lieutenant John “Johnny” Godfrey and Captain Dominic “Don” Gentile (a soft-spoken first-generation American also known as “Gentle”) found themselves in a massive dogfight with German fighters over Berlin. Several American bombers had already gone down. The sky was full of burning planes, debris and parachutes.

Both Godfrey and Gentile were from the US 336th Fighter Squadron, of the 4th Fighter Group — the longest-serving US fighter group in England (and the predecessor of the modern USAF 4th Fighter Wing)

The Hated P-47

The 4th Fighter Group had taken receipt of its first P-51Bs on 14 February 1944 (Fry, Garry L & Jeffrey L Ethell, Escort to Berlin, NY: Arco Publishing, 1980, pg. 38) — to the jubilation of the unit pilots who finally saw the chance to rid themselves of the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter.

In fact, the 4th Fighter Group, which had its origins in the “American Eagle” squadrons of the British Royal Air Force (RAF) — three squadrons made up of American volunteer pilots who had joined the RAF before the USA joined the war — positively sneered at the P-47.

The P-47 was big and ungainly looking, with large frontal maw feeding air into a massive rotary engine. It could dive like a boulder and flew like one under 18,000 ft. Its performance at higher altitudes was better but its maneuverability remained poor when when compared to the Luftwaffe’s nimble Messerschmitt’s Me109s and Focke-Wulf Fw190s.

“So, for a time the 4th went moodily on, flying Thunderbolts,” wrote an 8th Air Force Public Relations officer, Grover C Hall. (1000 Destroyed: The Life and Times of the 4th Fighter Group, 1946).

“It was a lack-luster period for the 4th. They were saying the Thunderbolt was not fit for combat… To the ex-Eagles, the Thunderbolt was a lumbering, over-rated crate that wouldn’t climb, wouldn’t turn and whose cockpit had a way of gathering smoke from burning oil, often unnerving the pilot,” Hall added.

According to Hall, the group had “craved” a P-47 replacement since 1943. If the group lusted after the Mustang, it was because the P-51 was like the British Supermarine Spitfire that they flown in the RAF — “fragile and waspish beside the massive Thunderbolt, but wicked looking with its capped wings and razor back.” (Hall, 1000 Destroyed)

However, at the same time, the US 56th Fighter Group (the so-called “Zemke Wolfpack,” named for its leader, Colonel Hubert Zemke), was racking up kills with the P-47. This was because the “Wolfpack” had evolved special tactics to utilize the strengths of the P-47, such as its superior roll rate.

According to Hall, the “4th Group accepted… the fine performance of the Wolfpack with churlish ill-grace.”

A fair amount of jealousy that the 56th was able to elicit wonders from that crate, the Thunderbolt, spurred such resentment from the 4th. While the 56th already had a bag of 300 kills by the start of 1944, the 4th only had 150.

“[So] the ex-Eagles molted and sulked and explained to the satisfaction of none, that ‘They [the 56th Fighter Group] boogar off and don’t protect the bombers like we do’, or, ‘Oh, they’re just getting a lot of that easy-meat twin-engined stuff’,” Hall wrote.

When the P-51s started arriving from February 1944, the overjoyed 4th Fighter Group promised to get operational with the type within 24 hours. The 4th’s commander, Lt. Colonel Donald Blakeslee, said that the group would “learn to fly ’em on the way to the target.” (Hall, 1000 Destroyed)

The P-51 had massive potential. The British Air Fighting Development Unit (AFDU) studied the P-51 in detail. Unlike the P-47, the P-51 was found to be superior to the German Fw190 in nearly all respects. It was faster by 50 mph, could climb faster, always out-dive the Fw190 and out-turn the Fw190 in a dogfight. However, the Fw190 had a superior roll rate. (Price, Alfred, The Strategic Air Offensive over Germany, Vol 2, 1943-45, Classic, 2005, pg. 200-201)

The Terrible Twins

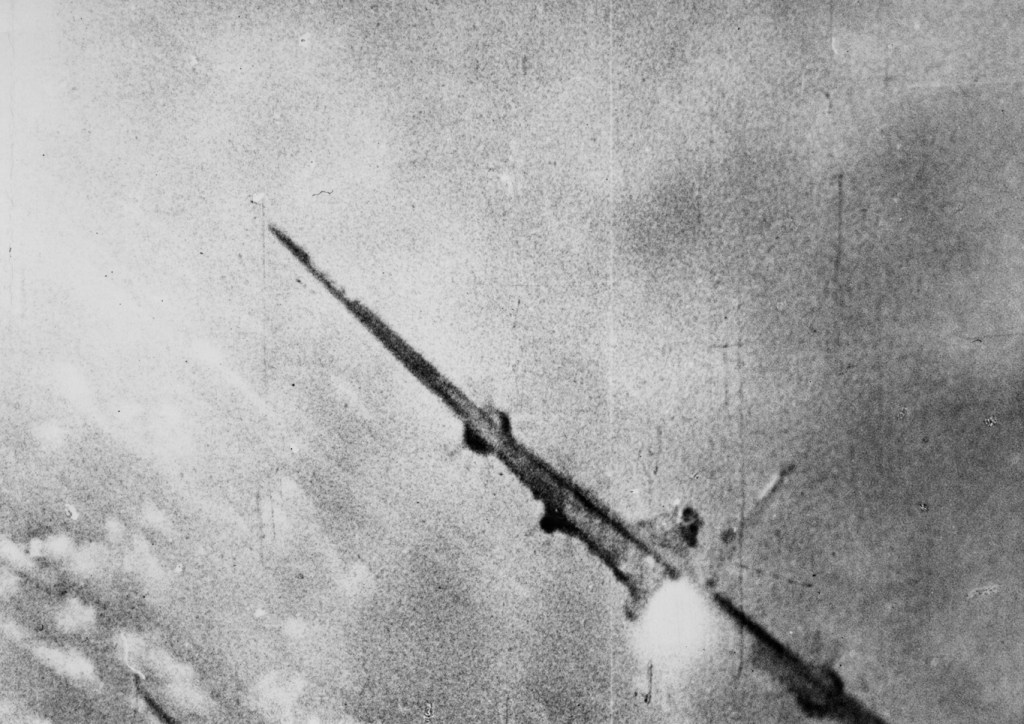

Back on 8 March 1944, over the suburbs of Berlin, Gentile (flying P-51B VF-T, no. 43-6913) and Godfrey (flying P-51B VF-P, no. 43-6765) found that most of the Allied escort cover had withdrawn, leaving the US bombers at the mercy of nearly 60 Luftwaffe fighters. Working together, the two men rapidly shot down three German Messerschmitt Me109 fighters. Nearby, green SOS flares appeared in the sky, launched by a bomber group under attack. The pair raced to help. With guns blazing, they scalped two more Me109s off the bombers.

In 20 minutes over Berlin, Godfrey and Gentile blasted a total of six German fighters from the sky before they ran low on ammunition. The kills gave Godfrey enough victories to become an ace while Gentile increased his score to 11.83 enemy aircraft confirmed as destroyed.

Emboldened, both men painted red-and-white checkerboards on the noses of their P-51Bs and decided to work together as wingmen in future missions. They quickly came to embody the US Army Air Force’s (USAAF’s) theme of teamwork.

As March 1944 chugged on, 8th Air Force fighters solidified their position over the Luftwaffe through escort missions aimed at scattered aircraft and ball-bearing plants. The US ace race had also switched to top gear as various ETO (European Theater of Operations) fighter pilots vied for the place of “top ace” during the last days of March and April 1944.

Much of the clamor was goaded by the American Press, which wanted to see which pilot would break US Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s 26 victory tally from World War I. No American pilot had yet come close to that score although several pilots in the Pacific were drawing close.

The top-scoring 8th Air Force pilot of the time was Captain Robert S Johnson of the 56th Fighter Group with 22 kills. But Gentile and another highly-ambitious 4th Fighter Group ace pilot, Captain Duane “Bee” Beeson, were closing in with 14 kills.

On March 23, during a raid on Luftwaffe airfields in western Germany and aircraft factories at Brunswick, Beeson and Gentile both shot down two Me109’s to reach 16 victories each. After the new commander of the 8th Air Force, Major General Jimmy Doolittle, decreed that German planes destroyed on the ground also counted as “kill”, many US fighter pilots began beating up the Luftwaffe airfields to inflate their scores.

The Luftwaffe credited the Americans with due success in this sort of indiscriminate hit and run strafing attacks. One German report stated that “the enemy has…put aside a part of the escorting force to attack our …[aircraft on the ground] and has achieved success. (Ultra and the History of the US Strategic Air Force Europe vs. the German Air Force, pg. 53)

Another German report stated that “Enemy fighters are carrying out attacks on aircraft which are landing or in airfield themselves …They imitate the landing procedure of German fighters or effect surprise by approaching the airfield in fast and level flight. The difficulty in distinguishing friend and foe make it impossible for flak to fire on them. (Ibid., pg. 156)

However, the ground-based flak began claiming more allied pilots than Luftwaffe fighters did. Single-seat Mustangs and Thunderbolts, plus twin-engine Lightnings would lurk about the airfields, watching for exposed aircraft on the tarmac. As soon as the targets presented themselves, the American pilot would dive “downstairs,” skimming low – barely a few feet off the ground – to keep out of the ack, before lining up in their targets and opening fire.

The danger was terrific. Pilots had to plan their attack with care, but mistakes were common. Pilots hit the ground in their haste to get German planes in their gunsights, or found themselves taking ground fire when slowing down to take aim. High-speed and a steady aim were key ingredients to success. A single pass was all that was usually possible before the flak found its mark. But many pilots came back for more – either surviving to fly again or at best, ending up as prisoners of war (POW). Among those lost was Beeson who was shot down on 5 April 1944. He became a POW at Stalag Luft I.

Undeterred by the losses, Godfrey focused on ground strafing and destroyed over a dozen German planes as they stood on their hardstands at airbases. Gentile preferred air combat. The two became media darlings and elevated Allied press coverage of the 4th Fighter Group. The German Luftwaffe (air force) called the pair, “Terrible Twins” and their chief, Hermann Göring, swore with typical braggadocio that he would sacrifice two squadrons for their capture.

But it was the USAAF which broke up the team. On 13 April, Gentile who was returning from a mission (his last before he was due to return to the US for a publicity tour), decided to buzz the airbase in an effort to show off for the press. His Mustang clipped a bit of high-ground and crashed.

Gentile lived but standing orders from the group commander, Blakeslee, was that anyone who “pranged a plane while stunt-flying was to be kicked out of the group.” ( Fry & Ethell, Escort to Berlin, pg. 49) Gentile was out of the group — and out of the war.

He and Godfrey went home in early May 1944, leaving behind a legacy of 15.33 German aircraft destroyed in the air, in three weeks of combat.

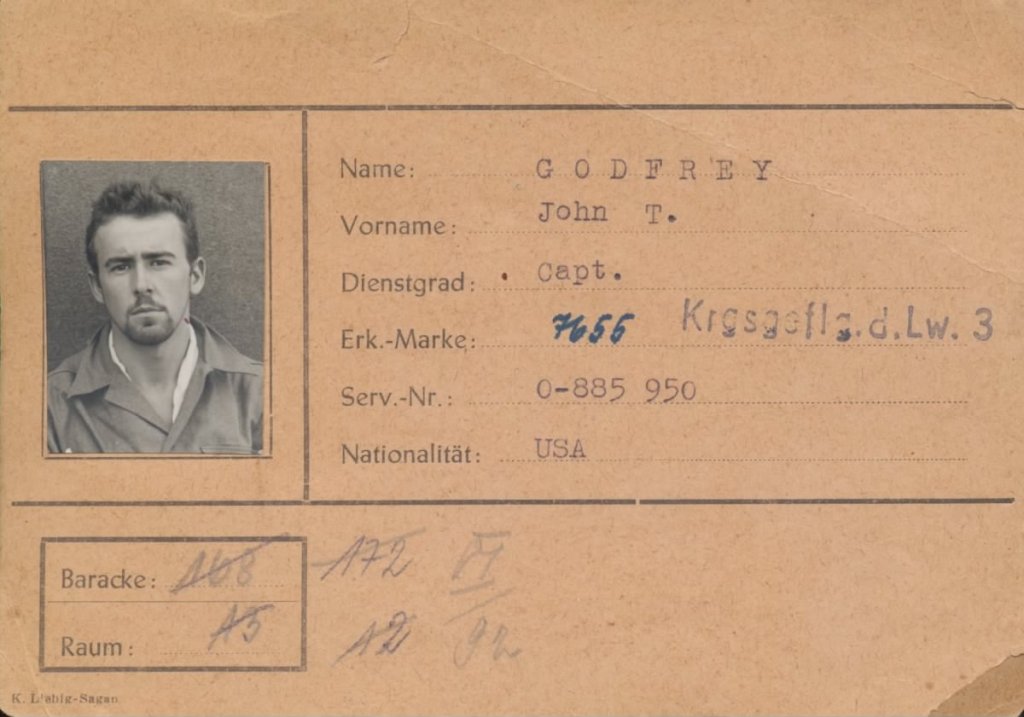

While Godfrey returned to combat from his bonds drive in May 1944, he was accidentally shot down on 24 August by his wingman during a strafing attack on a Luftwaffe airfield. Captured, he was met by Hannes Schraff, an expert interrogator at the Luftwaffe’s Dulag Luft (POW transit camp) at Oberursel. Schraff greeted Godfrey as one would an old friend, but got down to business.

“Now look, Johnnie,” he said, “We both know why I’m here talking to you. What we want to know is how you Americans spot those airdromes.”

Godfrey stuck to his rank, name and serial number, as advised by British MI-9 and the American MIS-X, the POW advisement agencies. The job of both agencies was to plug POW information leaks, devise escape aids for shot-down aircrews and send coded messages to POWs in letters.

Scharff then proceeded to hit Godfrey with a series of personal questions, such as if a friend’s baby had been born yet or if he had delivered a friend’s letter to an uncle in the United States. Most of the information came from Allied magazines and newspaper articles. Parroting such intimate information was an attempt at disarmament, designed to throw off hapless captives from their preconceived stubbornness and impress upon them that it was futile to believe that they could hide anything from their captors.

As annoying as the questions were, Godfrey’s greater consternation was that he was out of the war. Held as a POW at Stalag Luft III at Sagan, he escaped in the last few days of the European war. But his combat flying days were over.

Small Towners

In the years after World War II, the US Air Force attempted to determine the qualities required to be an “ace” pilot in the war.

Patriotism helped but two characteristics stood out: most of the US ace pilots came from small towns or farms and this often meant they had experience with a rifle-shooting, including how to get a bead on targets and “leading” them. (Keeney, L Douglas, Gun Camera Footage of World War II, MBI Publishing 2000, pg. 57)

The data shows that not only were a majority of the top aces in the 8th Air Force from rural backgrounds but so too were some Germans. There were exceptions among the Americans, of course, such as Colonel David Schilling who was a city boy as was Major James Goodson who had also largely grown up in an urban landscape.

The Brutality of Total War

Whatever their backgrounds, the air war consumed them in its intensity. This was “total war” where no quarter was given and none asked for. Occasionally parachutes were strafed, straggling aircraft were shot up without remorse and bailed-out allied airmen manhandled by irate German civilians, who could not fathom why the Americans had joined the war. They had forgotten that it was Germany that had declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Total war is not a succession of mere episodes in a day or a week. It is a long drawn-out and intricately planned business and the longer it continues, the heavier are the demands on the character of the men engaged in it. – General George C Marshall

A case of “total war” was illustrated during an engagement between “Bee” Beeson and an especially proficient Luftwaffe pilot on 23 March. The German, an obvious veteran outmaneuvered every shot Beeson that threw at him. Finally, in a moment of error, the German committed a fatal mistake in maneuvering and was punished with a barrage of machine-gun fire.

His plane shot to pieces, his engine faltering, the German belly-landed in a nearby field. Even before the aircraft came to a stop, the heavily-framed canopy was flung aside and the Luftwaffe pilot was seen scrambling for cover across the open field.

Beeson bore down on him and remembered thinking: “he’s a fine pilot. If I let him go, he’ll get another plane and be up again tomorrow. He may explode a bomber with ten Americans in it or he may shoot me down next time.” (Hall Jr., 1000 Destroyed, chapter 13.) With that he pressed the gun button, and strafed just as the fleeing German reached shelter behind a hedge. Whether or not the German was hit, Beeson could not tell.

Later, in 1944, Captain Richard “Bud” Peterson, an ace from the US 357th Fighter group came upon a German fighter purposefully killing bailed out US bomber crews in their parachutes. Killing people in parachutes was against the Geneva Convention’s rules of war.

“This sonfabitch was going from parachute to parachute, shooting up guys in parachutes,” Peterson recalled in an interview in the 1990s (see below).

Peterson hacked away at the German fighter with his guns until the pilot bailed out. The opportunity for revenge had arrived. “I damned near emptied my guns on him [after that],” Peterson said.

The brutality of the air war was such that even civilians were unsafe. Farmers and laborers on fields were sometimes strafed by US fighters and predictably, the end result led to many allied airmen being lynched soon after parachuting the ground – even if they happened to be innocent of such atrocities.

The US 8th Air Force’s destruction of the Luftwaffe’s fighter force, robbed Germany of all options to reclaim air superiority, even after the introduction of the Messerschmitt Me262 jet fighter. Without air superiority, the German army was bereft of the air cover necessary to win counter-offensives. The P-51 Mustang and the air aces may not have won the war for Allies, but without them, achieving final victory would have been harder.

bonjour

encore un super travail, question : à l’occasion du 80è anniv du débarquement, avez vous le projet de produire d’autres articles et cartes, venant compléter le superbe travail déjà effectué sur ce sujet

encore merci pour vos créations , en particulier les cartes inégalées en ce qui me concerne

Michel POUPLRD (Rennes-Bretagne)

Hi Michel, Thanks for your message. I was considering a special ebook for the anniversary but the high-resolution maps are problematic when it comes e-book publication. I and an associate are considering the options.

More than D-Day, I have quite a bit of unpublished material and maps on the fighting inland at Normandy. Trying to work out a plan for them.

Superb- I thoroughly enjoyed digesting this information. As usual your research is comprehensive and has such a great balance between the factual and the anecdotal. I loved the graphs and the spreadsheet on the killer elite. Keep up the good work, it is truly inspiring.

Many thanks for your kind comments! The feedback is invaluable.

I have always had a passing interest in anything related to WW2 and I am an avid collector of German paperwork, particularly from the North African campaign. This is a particular are of interest. I enjoy the detail you provide. If you have anything related to the North African theatre of war, I would greatly appreciate it.

I was working on a detailed map infographics covering the entirety of the campaign and another on Popski’s Private Army. But that is hold because of other projects.