Stacked Dominoes

This was the first time that Montgomery, the master of tactical battle, completely underestimated the enemy strength – Brian Horrocks

The operation was due to launch on 17 September 1944. The Garden forces were required to reach Arnhem in 36 hours at the earliest; 48 hours at the latest. A single mishap could upset the domino-like precision which the plan relied on for success.

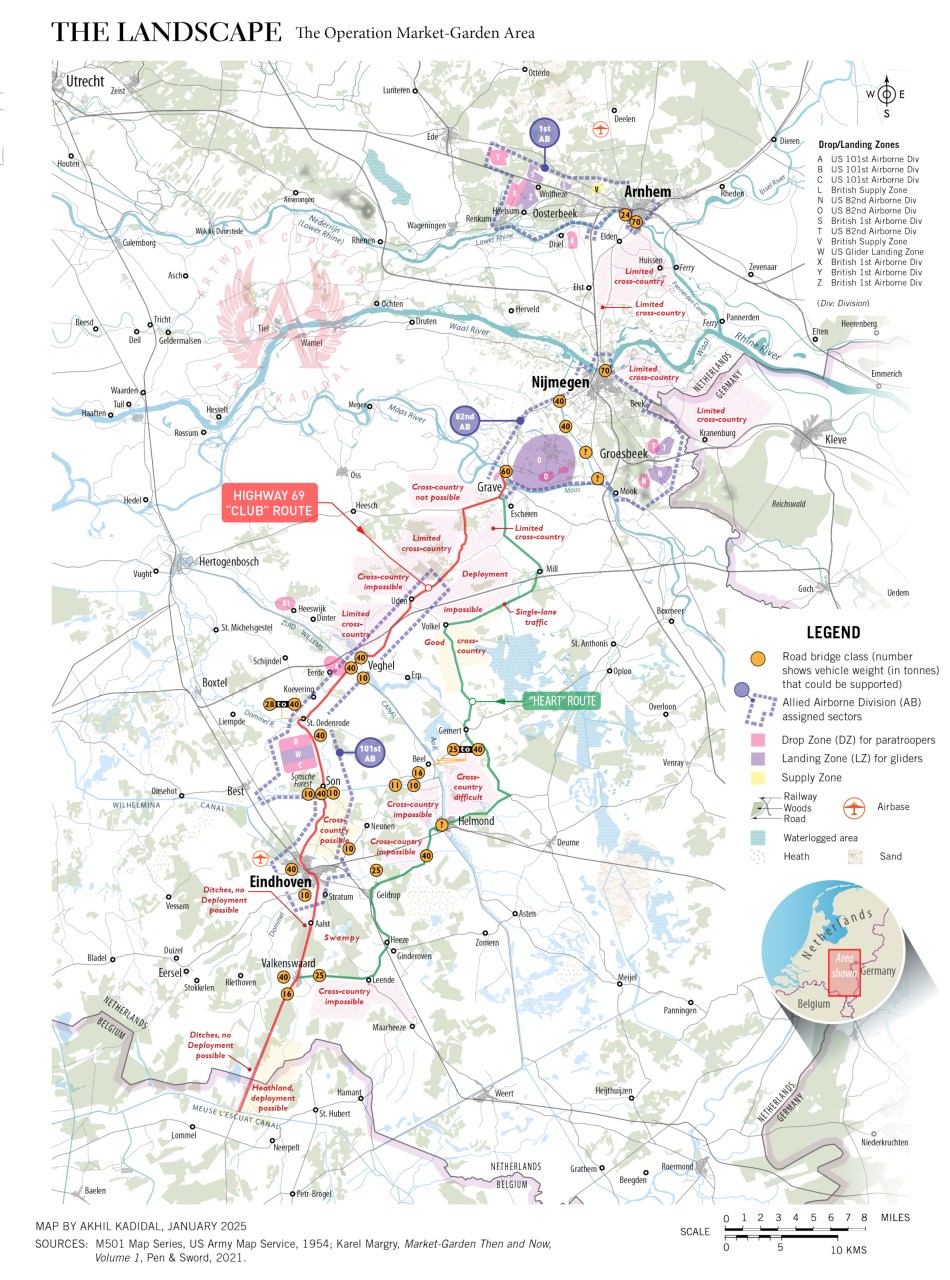

The landscape of the Netherlands is marsh-like; the terrain crisscrossed by rivers, streams, and swamps. Allied planners identified at least 30 important bridges (or varying size) between Valkenswaard and Arnhem to support the advance of Horrocks’ XXX Corps.

The British airborne had to secure two bridges at Arnhem. The US airborne had to secure about 12 crossings over seven waterways. (Buckingham, pg. 9) If the Germans destroyed enough bridges, the British ground advance could flounder.

German strength itself was improperly studied. Allied Intelligence believed that the German Army on the northwestern front had been smashed — An impression that the Dutch populace on the ground initially shared.

From 4 and 5 September 1944, the Dutch watched in quiet jubilation as a horde of fatigued, demoralized German troops started to filter through the eastern Netherlands – through Eindhoven, Nijmegen, Arnhem, and all the tiny hamlets, villages and towns along the way. A rumor spread that the Allies had smashed through German units along the Belgian-Dutch borders and were surging into the Netherlands.

Since the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, the Dutch had been waiting for the moment of their own liberation. Now, it appeared tangibly close.

The flood of German detritus passed through however they could, on foot, on horse-carts, on stolen bicycles, on trucks, and on trains, headed northeast, back towards Germany. They were accompanied by refugees (Dutch collaborators and women who had been romantically involved with German soldiers). (Harry Kuiper, Arnhem and the Aftermath, (Pen & Sword, 2019), pg. 105-107)

At the town of Velp (just east of Arnhem), a 16-year-old Dutch-English girl, Adriaantje van Heemstra, watched the German rabble go past. “Adriaantje” was a pseudonym for the girl’s real name, Audrey. It had been assumed to conceal her part-British heritage from the Nazis. After the war, the young girl would go on to fame as Audrey Hepburn.

Her father, a British-Austrian businessman, Joseph Hepburn-Ruston, had abandoned the family 10 years ago. Audrey’s Dutch mother, Ella van Heemstra had subsequently move them to Arnhem, to live with her sister Meisje and her own husband, Count Otto van Limburg Stirum.

Hepburn was close to her uncle, but then the Nazis executed the Count in August 1942 in reprisal for an attack by the Dutch resistance. This act, coupled with Hepburn witnessing other Nazi crimes, began to push her towards aiding the Dutch resistance. (Audrey Hepburn’s secret role in WWII, BBC Radio 4)

Hepburn saw Jews (families with little children, even babies) separated and herded into cattle cars. She often saw the routine killings of Dutch civilians in Arnhem. “We saw young men put against the wall and shot, and they’d close the street and then open it and you could pass by again…. Don’t discount anything awful you hear or read about the Nazis. It’s worse than you could ever imagine,” she said later. (Barry Paris, Audrey Hepburn (Berkley Books, 2001), Ch 1, 5%)

After the Count’s death, Hepburn (with her mother and aunt Meiseje) left Arnhem and moved to the neighboring town of Velp to live with with her grandfather, Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra. Hepburn became a courier and messenger for the resistance. But she was hardly unique in this role, as she later said, explaining that “every loyal Dutch school girl and boy did their little bit to help.” (Warren Harris, Audrey Hepburn, (Simon & Schuster, 1994), pg. 39)

“Many were much more courageous than I was,” she added. “I’ll never forget a secret society of university students called Les Gueux (The Beggars)10, which killed Nazi soldiers one by one and dumped their bodies in the canals. That took real bravery, and many of them were caught and executed by the Germans. They’re the type who deserve the memorials and medals.” (Harris, ibid.)

Fast forward to September 1944, Hepburn and her family watched amazed as a solid mass of weary Germans passed through Velp, only stopping to loot Dutch homes and steal whatever they could. (Robert Matzen, Dutch Girl, (GoodKnight Books, 2019), Part IV, Ch 21, 42%)

But no Allied troops appeared in their wake and almost in unison, the Dutch realized that the Germans were regrouping.

German Battlegroups Form

Ultra (the British intelligence program which had broken German military codes), discovered that German units were taking up station in the Arnhem area. Among them was SS Lt. General Wilhelm “Willi” Bittrich’s II SS Panzer (Armored) Korps, formidable veterans from Normandy.

Having been nearly destroyed in Normandy, the Korps was trying to recuperate in the Arnhem area. Ultra, however, had little information on its current status. (Buckley & Preston-Hough, Ch 1, loc. 544)

Hepburn herself counted several operational SS tanks parked in front of their home, Villa Beukenhof (at 32 Rozendaalselaan), before the German armor rumbled up the boulevard and into the surrounding woods. (Matzen, 42%).

Remarkably, Allied intelligence believed that a core formation in Bittrich’s command, the 9th SS “Hohenstaufen” Panzer Division, was near Aachen, nearly 80 miles south of Arnhem. In reality, the 9th SS (under the temporary command of SS-Oberführer Walter Harzer) was recuperating and reorganizing at Apeldoorn, less than 15 miles north of Arnhem.11

Another SS division, the 10th “Frundsberg” Panzer, was recovering near Lochem and Zutphen, about 16 miles northwest of Arnhem.

Despite being battle-hardened, both divisions were in poor shape. The 9th SS “Hohenstaufen” had a strength of about 6,000 men in early September 1944. Back in Normandy, the division had 15,898 men (as of 30 June) and 79 tanks. (Niklas Zetterling, Normandy 1944, (Casemate, 2019), 75%). It had lost most of its strength in Normandy.

Despite its diminished standing by September, the division had one distinct advantage. Early in its history, it had received special training to counter airborne landings. It would put that training to use in the days to come. (Wilhelm Tieke, In the Firestorm of the Last Years of the War, (J.J. Fedorowicz, 1999), pg. 4)

The 10th SS “Frundsberg,” under SS Brigadeführer Heinz Harmel, had less than 3,000 men, but with larger quantities of heavy equipment: eight Panther tanks (all inoperative), 10 Panzer IVs and 20 Jagdpanzer IV tank destroyers, 57 artillery pieces, 28 flak pieces, and 37 halftracks.12

On 10 September, the 9th SS was ordered to transfer its remaining operational vehicles to the 10th SS Frundsberg. Remnants of a Hohenstaufen grenadier and artillery battalions were transferred to Kampfgruppe Walther in the south, where they would soon encounter the US 101st Airborne Division. The 9th SS, however, retained 30 armored cars under SS Captain Viktor Gräbner, a Normandy veteran whose unit would go down in the history books for all the wrong reasons.

With its strength now down to less than 3,000 men, three Panther tanks, two Jagdpanzer IVs, Gräbner’s armored cars, and a handful of anti-aircraft guns, the 9th SS prepared to return to Germany for refitting. (Robert Kershaw, It Never Snows in September, (Ian Allen, 2004), pgs. 38-39) The Allied airborne arrived before the 9th SS could go home.

Other German units in the eastern Netherlands were also in bad shape, having lost heavily in Normandy and in the subsequent retreat. Army Group B commander, Field Marshal Walter Model, was hard pressed to muster a defensive line.

The tactless, foul-mouthed Model was not the best liked commander in the German army, regarded disparagingly by senior officers as Frontschwein (Frontline Pig). (Steven H Newton, Hitler’s Favorite Commander, (Da Capo, 2006), pg. 162) Model, however, was adept at improvisation and was already cobbling together battlegroups.

As Horrocks later said, “in every country that has been engaged in a long war there are half-forgotten formations which have come to exist almost in their own right… and these were to be found even in [Nazi-occupied territory] in the autumn of 1944.” (Brian Horrocks, Corps Commander, (Lume Books, 2023), pg. 115)

Model intended to use these motley forces as the bulwark of his defenses.

Consequently, when the German defensive line was thrown across northern Belgium and the southern Netherlands, it was formed using a mixed bag of kampfgruppen (battlegroups).

These were composed of all manner of troops: from battle-hardened fallschrimjägers (paratroopers) to the gutted remnants of battle-hardened panzer (tank) and panzerjäger (tank destroyer) units, from training personnel and new recruits to convalescents cases and stragglers, from gunners without artillery to sailors without ships, and even martial band members who had their trumpets, drums and cymbals replaced with rifles, helmets, and grenades. (See Horrocks, pg. 115 & Kershaw, pgs. 21-25)

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean