Warfare is a product of the worst of human excesses and in World War II, Operation Market-Garden was almost no different, if not for its nobility of purpose, and civility in battle. The British-US operation was an ambitious effort to hasten the end of the war by the Christmas of 1944. Instead, it went so wrong that eight decades later historians are still trying to understand what failed and why.

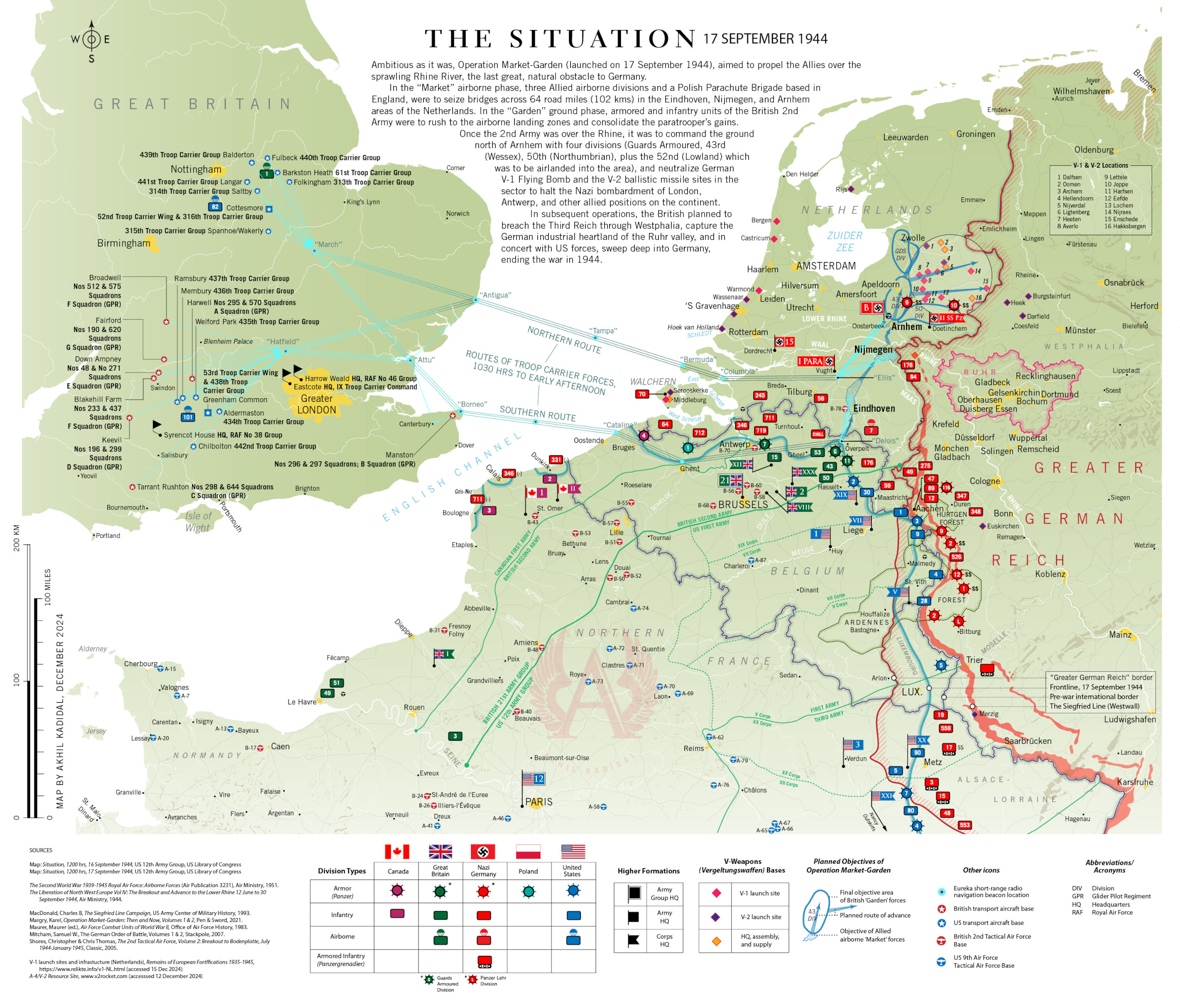

Conducted in the last autumn of the war, the operation aspired to propel the Allies through the eastern Netherlands and over the sprawling Rhine River (the last, great natural obstacle to Germany). From there, the Allies had a spring-board from which they could strike into Germany and attack its capital, Berlin. That dream collapsed around the destruction of the elite British 1st Airborne Division at the Dutch city of Arnhem.

That failure, occurring at the height of Allied military fortunes in the war, provided a stunning reminder of the old von Moltke1 maxim that, “no plan of operation survives first contact with the enemy” – Especially, a hastily developed plan that assumed that the Nazis were already beaten.

Market-Garden became better known to the general public in the postwar period. In 1946, a British film, Theirs is the Glory, filmed with 1st Airborne Division veterans in the ruins of the actual battlefield, opened to public acclaim. However, the film did little to dispel the public’s misconception that only the British Army was involved in a struggle which in reality, had also cost two US airborne divisions dearly.

A spate of memoirs by British commanders and minor histories followed.

Then came the 1974 history, A Bridge Too Far by the Irish-American journalist, Cornelius Ryan. This book gave the US airborne their dues, while creating a stunning picture of heroism, sacrifice, and stupidity. A later reprint provided this writer’s introduction to the battle, as a teen.

Despite its depth, the book did not provide all the answers. Without detailed maps on the subject, following the complexity of the battles becomes difficult, especially the convoluted battle of Arnhem. For years (until recently, I confess), I failed to grasp what had really happened and where, during obtuse battles fought in esoteric places called Ginkel, Grave, Renkum, Beek, Wolfheze, Son, and Mook.

Could these have also been the names of comic characters of another childhood? They might have been.

A 1977 film adaptation of Ryan’s book, made with a gamut of stars from Hollywood and Pinewood, reinforced some of the deficiencies of the book, including the myth that the operation failed because the 1st Airborne landed on two fully operational Waffen-SS armored divisions.

If Market-Garden has cemented itself in the public consciousness over the decades, it is because of its daring, and because of its humanistic objectives. Allied combat operations, especially in northwest Europe, were acts of liberation, fought to restore democracies and democratic institutions.2 At its essence, Market-Garden aspired to achieve this grand goal.

While the operation caused horror and tragedy, it also brought out the best in people. The heroism and sacrifice of its Allied protagonists triggered enduring gratitude from the Dutch. Surprisingly, it also elicited sentiments of honor, even decency from the Nazi combat cadre, the Waffen-SS — in spite of their moral decline which was nearly complete after five years of war and six years of nationalized racial indoctrination.

The operation’s failure, however, has caused it to be refought hundreds of times in books and films, fed by public curiosity.

Will I do some refighting of my own in the words that follow? A little. My larger objective was to use primary source statistical data (and select secondary sources) to recreate the battles through maps, infographics, and analysis. The intention is to offer a new and clear perspective of the operation.

- The Gamble

- The Politics of Warriors

- Stacked Dominoes

- All Hell Breaks Loose

- Arnhem, the Alamo

- The 8nd Airborne and a Narrow Run Thing

- The US 101st Airborne’s Frontier War

- Point of No Return

- Aftermath

- Footnotes

- Credits & Bibliography

The Gamble

Against a defeated and demoralized enemy almost any reasonable risk is justified and the success attained by the victor will ordinarily be measured in the boldness, almost foolhardiness, of his movements – Dwight D Eisenhower

By the start of September 1944, the Allies found themselves nearly the masters of northwestern Europe. The tattered remnants of Germany’s primary battle force in the region, Army Group B, were in headlong retreat after their defeat in Normandy.

The Allies were in pursuit, sweeping through northern France. Paris fell on 25 August and the Allies approached Belgium. Up to early September, one-third of British General Bernard “Monty” Montgomery’s 21st Army Group3 were clearing German forces from ports along the English Channel while the rest pushed into Belgium.

But the Allied advance was congealing. The Anglo-Americans armies were outrunning their supply lines. Nearly every port recovered from the hands of the Germans was in ruins. This limited the amount of supplies that could be landed.

Many operational ports were also in or near Normandy, which was receding into the distance as the frontlines radiated out towards Germany. The British captured the valuable deep water port at Antwerp on 4 September. But the harbor was unusable because German troops held the approaches, along the Scheldt River estuary, and especially on Walcheren island.

Compounding the problem was growing German resistance.

Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, the commander of the British Army’s XXX (30) Corps would later note (with hindsight), that the Germans were no longer in retreat by September 1944, and that Allied troops were fighting again. (Horrocks interview, World at War, “Pincers,” Episode 19)

Making the Case for Airborne Operations

Up to August 1944, the Anglo-American sweep across western Europe was so brisk that 16 Allied airborne operations (primarily involving the British 1st Airborne Division) were canceled between 6 August and early September because Allied ground forces overran the target areas before the airborne operation could be launched. (Karel Margry, Market-Garden Then and Now, Vol 1, (Pen & Sword, 2021), Part 1, Ch 1, loc. 643, 5%)

The most notable was Operation Comet, a British plan to use the 1st Airborne Division, the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, and the British 52nd (Lowland) Division (an air landing unit) to secure bridges over the Rhine estuary in the Netherlands (comprising the Waal, Maas and Lower Rhine rivers).

Under Comet, troops on 18 gliders were to land around the Arnhem bridge at about 0430 hrs on 8 September and seize the bridge in a coup de main. However, Comet was first postponed by bad weather, then canceled because of stiffening German resistance in northern Belgium, around the Albert and Maas-Schelde (Meuse-Escaut) canals.

Montgomery went to his superior, US General Dwight D “Ike” Eisenhower (the Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe) on 10 September, to elicit support for a new, bolder operation. An expanded version of Comet, he said. (Bernard Montgomery, From Normandy to the Baltic (Hutchinson, 1958), pg. 167)

The 10 September meeting was heated. Montgomery attacked Eisenhower’s broad-front strategy of a unified advance by four Allied armies4 along the nearly 600-mile Allied front that stretched from northern France to the Mediterranean. (Cornelius Ryan, A Bridge Too Far; pg. 90)

Instead, Monty demanded priority for his proposed push into the Netherlands. Such an action would not only win an Allied bridgehead over the Rhine, but also allow the Allies to outflank the German Westwall (Siegfried Line), Montgomery claimed. The Westwall was a fortified network of bunkers and tank traps that stretched for nearly 400 miles from the northern German city of Kleve on the border with the Netherlands, to the town of Weil am Rhein on the border with Switzerland.

The area north of Arnhem could also serve as a springboard to capture the Ruhr valley and even the German capital, Berlin, Montgomery said. His optimism envisioned an end to the war by December 1944.

Eisenhower demurred.

What Montgomery ultimately sought, Eisenhower was hesitant to give him – the bulk of Allied supplies and logistical support. According to Eisenhower, 36 Allied divisions were in action in western Europe by the end of August 1944, requiring a total of 20,000 tons of supplies every day from ports and beaches. (Dwight D Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, (Vintage, 2021), pg. 350)

The advances of these divisions required equitable distribution of available supplies.

Furthermore, “there was still a considerable [German military] reserve in the middle of the enemy country and I knew that any pencilike thrust into the heart of Germany such as [Montgomery] proposed would meet nothing but certain destruction,” Eisenhower wrote later. (Eisenhower, pg. 368)

Montgomery played his “trump card” (in the words of Cornelius Ryan). London was under siege from German revenge weapons – V1 flying bombs and V2 ballistic missiles. The launch sites were north of the Rhine, in the Netherlands. A British advance could nullify the launch sites, Montgomery said. (Cornelius Ryan, A Bridge Too Far, (Hodder & Stoughton, 2015), pg. 91)

This, and Montgomery’s claims that a foothold over the Rhine river would secure the Allied northern flank, held sway with “Ike.”

“To stop short of the [lower Rhine] obstacle would have left us in an exposed position,” the Supreme Commander conceded. (Eisenhower, pg. 369)

Crucially, Eisenhower regarded Monty’s proposal to secure a bridgehead over the Rhine as “merely an incident and extension” of the Allied “eastward rush.” (Ibid., pgs. 369-370)

This language gives the impression of a minor offensive. The scale of the operation which ensued was anything but trivial.

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean