The Politics of Warriors

War is politics by other means – von Clausewitz

Market-Garden aimed to capture key bridges across a 64 road mile (102 kms) stretch of the eastern Netherlands, across the Dutch cities of Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem.

In the Market phase, Allied airborne units would secure the key bridges and the three cities. In the Garden, ground phase, armored and infantry units of the British Second Army (specifically Horrocks’ XXX Corps) were to rush to the airborne landing zones and consolidate the paratrooper’s gains.

For the task, Eisenhower gave Montgomery the Allied theater reserve, the First Allied Airborne Army (FAAA), a recently formed unit colloquially known as the “First Triple A”. Commanded by US Lt General Lewis Brereton, the First Triple A comprised the British I Airborne Corps, the US XVIII Airborne Corps, and the US IX Troop Carrier Command.

First Allied Airborne Army5

(US Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton)

British I Airborne Corps (Lieutenant General Frederick “Boy” Browning)

British 1st Airborne Division (Major General Roy Urquhart)

British 6th Airborne Division (Major General Richard Gale)

Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade (Major General Stanislaw Sosabowski)

British Special Air Service (SAS) units

British 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division (Major General Hakewell-Smith)

US XVIII Airborne Corps (Lieutenant General Matthew B Ridgeway)

US 82nd Airborne Division (Brigadier General James Gavin)

US 101st Airborne Division (Major General Taylor)

US 17th Airborne Division (Major General William M Miley)

US 507th Independent Parachute Infantry Regiment (Colonel Edson Raff)

US 878th Airborne Aviation Engineer Battalion

US IX Troop Carrier Command (Major General Paul Williams)

RAF No 38 Group (Air Vice-Marshal Lesley Hollinghurst)6

RAF No 46 Group (Air Commodore L Darvall)7

Montgomery decided to use select units from the First Triple A: the British 1st Airborne Division and the Polish 1st Parachute Brigade (made up of highly-motivated anti-Nazis who had scores to settle with Germans over the conquest of their homeland). Also included were the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions which were extricated from Lt. General Matthew Ridgeway’s US XVIII Corps which itself was left out of the operation – much to Ridgeway’s resentment.

Montgomery could not commit with the entirety of the Airborne Army as he had to ensure that reserves were available to exploit a breakthrough. Also, there were not enough aircraft available to transport the entire army to the continent.

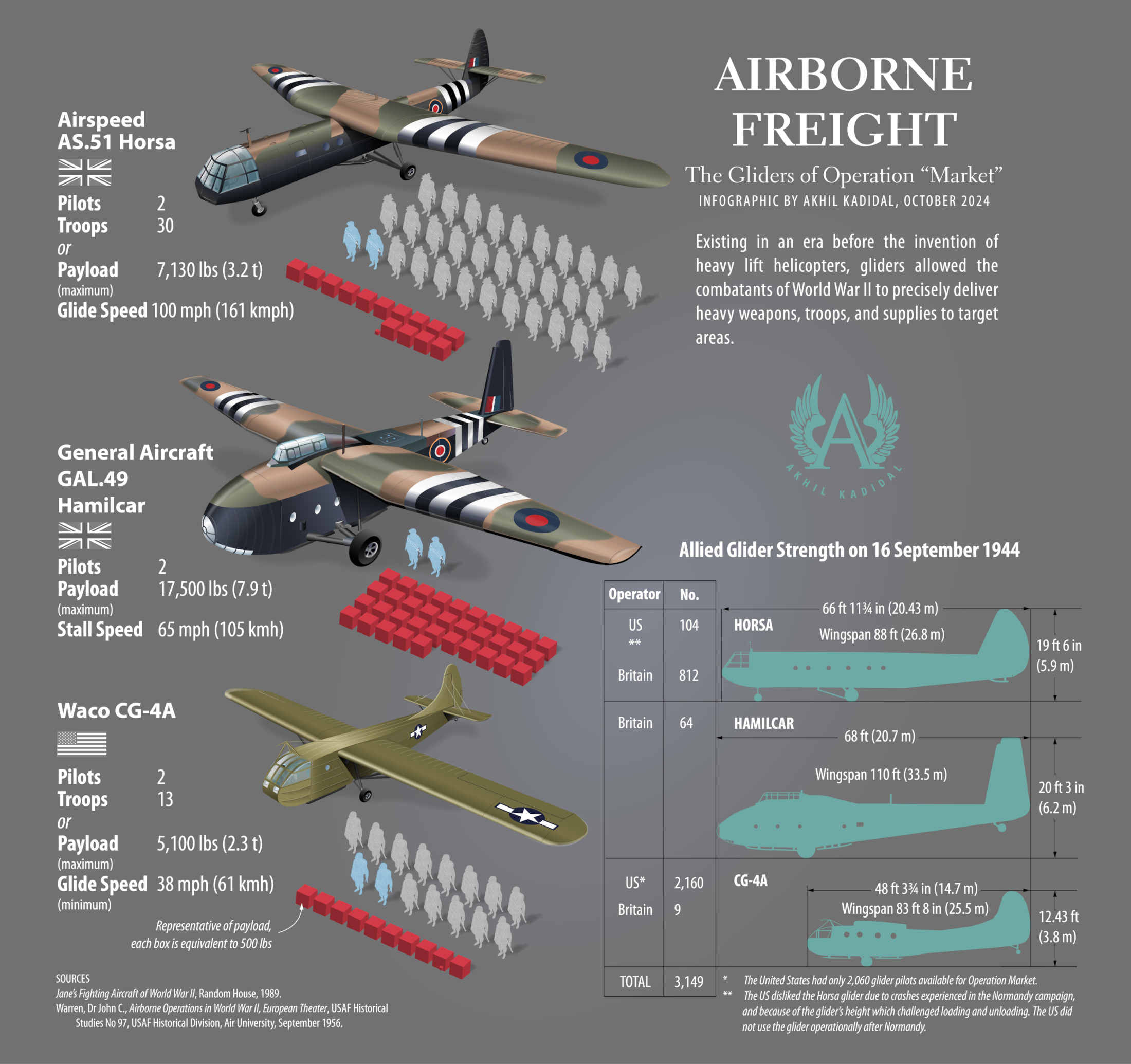

Eisenhower’s approval of Market-Garden handed Montgomery control of over 3,149 British and US troop- and equipment-carrying gliders. Also at “Monty’s” disposal were 1,274 Douglas C-47 transport aircraft of US IX Troop Carrier Command in England. The RAF’s No 38 and 46 Groups had another 485 troop-carrier and glider-tug aircraft available for the operation. (See John C Warren, USAF Historical Studies No 97, Air Operations in WWII, USAF Historical Studies No 97 (USAF Historical Division, Air University, September 1956) & Air Invasion of Holland, (IX Troop Carrier Command Report on Market, SHAEF, 2 Jan 1945))

While these numbers seem sizable, even this fleet of aircraft would require three separate airlift operations to transport the selected airborne units to the objective.

Once British forces secured Arnhem and nearby Deelen airfield, north of the city, Montgomery planned to fly in the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division.

Operation Market was shaping up to be the largest airborne operation in history. For the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, some 25,000 airborne troops8 were dropped into battle but Market would employ over 35,300.

In command of the airborne operation was British Lieutenant General Frederick “Boy” Browning, cultured, always immaculately dressed, but having little practical airborne experience, which, with his “scheming… high-handed and empire-building tendencies,” rankled the Americans. (William Buckingham, Arnhem: The Battle of the Bridges, (Amberley, 2019), pg. 84-86)

Browning “unquestionably lacks the steadying influence and judgment that comes with a proper troop experience basis,” wrote Brigadier General James Gavin, commander of the US 82nd Airborne Division, in his diary. (Lewis Sorley (ed), Gavin at War: The World War II Diary of Lieutenant General James M Gavin, (Casemate, 2022), pg. 251)

Browning was also no paratrooper. He told a subordinate that he had only done two jumps. “Hurt myself both times. I was terrified of breaking something.”9 (Roy Urquhart, Arnhem, (Pen & Sword, 2011), pg. 31)

Gavin was also unimpressed by Browning’s staff, describing them as “superficial”.

“They were all there and whenever possible, gave reasonable answers to questions asked, but totally lacked follow-up or even apparently an appreciation of what our requirements were,” Gavin said. (Sorley, pg. 251)

Ridgeway, for one, had taken a quick dislike to Browning.

Curiously, Montgomery appears to have been little involved in the planning of Operation Market-Garden. After the action began, he seemed a remote figure. Instead, Major General Paul Williams of US IX Troop Carrier Command and Air Vice-Marshal Hollinghurst of the RAF’s No 38 Group planned Market. (John Buckley & Peter Preston-Hough (eds), Operation Market-Garden: The Campaign for the Low Countries, Autumn 1944: Seventy Years On, (Helion, 2016), Ch. 2, loc. 952, 12%)

The air plan was finalized on 13 September and the order for Market-Garden was issued on 14 September. With only three days to go before launch day, everything became a blur of motion.

While “Monty” did not get all the priority of supplies he had hoped for, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) promised to deliver 1,000 tons of additional supplies a day to Brussels for the Garden troops. This met Montgomery’s minimum requirements. (Margry, Vol 1, Part 1, Ch 2, loc. 9.3)

The vanguard of the Garden forces, the British Guards Armoured Division, received orders to muster eight days worth of supplies, with the following British 43rd (Wessex) Infantry to gather six days worth of supplies. (21st Army Group: Operation Market-Garden: 17-26 September 1944 (SHAEF, 1945), pg. 13)

Poor Air Support

In a critical omission, supporting Allied tactical air forces were not consulted about their readiness before the operation was announced. Market is also unique as the only large airborne operation of World War II for which there was no prior training or exercise. (Warren, pg. 99; Buckley & Preston-Hough, Ch 1, loc. 501)

While steps were taken to provide the airlifts and the Garden forces with adequate air support, no steps were initially taken to ensure that the Allied airborne would have similar support after they landed.

The British 2nd Tactical Air Force (2nd TAF), a potent combat force which had played a part in the destruction of the German army in Normandy, was assigned to support XXX Corps during Operation Garden. However, no direct air support was planned for the 1st Airborne Division as it was believed that operating the 2nd TAF in the Arnhem area would interfere with transport and supply aircraft operations. (Allied Airborne Operations in Holland, September-October 1944 (SHAEF, 10 February 1945), pg. 23)

The 2nd TAF’s commander, Air Marshal Arthur “Mary” Coningham had also been omitted from planning meetings associated with Market-Garden until 16 September — less than 24 hours before launch. (Buckley & Preston-Hough, Ch. 5, locs. 925-1025 & 2571, 13% & 33%)

In-fighting among Air Commanders

Much of the poor coordination within the air forces was due to rancor among the senior personalities and their inability to work with each other.

Williams apparently did not heed Hollinghurst’s concerns during planning. Air Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory was the head of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF). He was designated commander of air support for the airborne forces. However, Eisenhower’s deputy, British Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, and Coningham both disliked Leigh-Mallory. They were conspiring to have him sacked. This prompted Leigh-Mallory (an arrogant man in his own right) to limit his professional interactions with Tedder’s and Coningham’s offices. Brereton also made himself distant from the operation. (Buckley & Preston-Hough, Ch. 5, loc. 1020, 13%)

Collectively, these machinations and inefficiencies would contribute to a significant absence of Allied air support at Arnhem and at Nijmegen where they would have made all the difference.

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean