Arnhem, the Alamo

There is nowhere else on earth to be but in the midst of 2nd Para when there is a battle on – John Frost

It would take extraordinary leadership and heroism to hold the bridge with just a battalion-worth of troops when it was supposed to be held by the entire 1st Parachute Brigade, but John Frost (known to his peers as “Johnny”) was no ordinary soldier.

Thirty-one years old in 1944, Frost was born in India on 31 December 1912, into an army family. His education and early career in the army were unremarkable. In 1932, he was commissioned as an officer into the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) Regiment and served in Palestine and Iraq, where he learned to speak Arabic. When World War II broke out in 1939, Frost was eager to get into action, but was unable to get a posting out of Iraq.

In 1940, Frost’s company clerk, an Indian named Sethi, handed him a piece of paper about the impending formation of a parachute battalion.

Frost was bewildered. “What on Earth made you think that I would be interested in this? You don’t suppose I would ever want to get involved in that sort of thing, do you?” he asked Sethi.

“You might be surprised… You never know all that is to come,” Sethi said. (Frost, loc. 363-375, 8%)

This incidental event set Frost on a reluctant trajectory towards the “Red Devils,” where, after intense training, he was posted to the newly formed 2nd Para in late-1941. The battalion and Frost then became involved in a series of sharp combat actions — at Bruneval (France) in February 1942, followed by Tunisia from November 1942 to April 1943, Sicily in July 1943, and Italy in September 1943.

At Arnhem, Frost deployed his troops in buildings around the bridge while his radio operators tried to raise the rest of Lathbury’s 1st Para Brigade only to receive silence. (Frost, loc. 3485, 73%) In actuality, the British had a ready-made communications solution that they had overlooked – the Dutch telephone network.

The Dutch resistance controlled at least three telephone systems: the national Ryks Telefoon system, the Gelderland Provincial Electricity Board (PGEM), and a secret network operated by resistance technicians which allowed the underground to call many places in the Netherlands without going through an operator. (David Bennett, “Airborne Communications in Operation Market Garden,” Canadian Military History, Vol 16, Issue 1 (2017), pg. 41)

But the British distrusted the Dutch resistance under the impression that German agents had penetrated the network and so, the telephone system went unused. (see Ryan)

From Frost’s perspective, all he had to do was hold on until the Garden forces reached him. According to the schedule, the Guards Armoured Division was due to reach the bridge at “lunch-time” on 18 September. (Frost, loc. 3425, 73%)

It was a schedule that the Guards would not keep. Frost and his men would have been appalled to learn that instead of racing towards Arnhem night and day, the Guards were insouciantly settling into the Valkenswaard on the night of 17 September after having covered just 7.4 miles from the Belgian border, which itself took them three hours to traverse.

Arnhem was 56 miles road miles from Valkenswaard.

According to Horrocks, the Guards halted on orders from Brigadier Norman Gwatkin, commander of the 5th Guards Brigade, after he learned that the Germans had blown up bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal, in the 101st Airborne’s sector. (Horrocks, pg. 138)

Efforts were underway to set up a Bailey bridge (a portable, prefabricated, truss bridge) over the canal, at the village of Son.

History would show that the Guards Division should have bashed on to the Son crossing to resume their advance as soon as the Bailey bridge was ready. As it was, it would take the Guards until 2100 hrs (9 pm) on the night of the following day, 18 September, to even reach the Son crossing. (WSEG Study No 3, pg. 88)

Destroying Gräbner

Meanwhile, Frost was aware of the precariousness of his position.

He foresaw that one of his biggest problems would be getting supplies to his isolated perimeter. As it was, the “British Army [was] notoriously cavalier when it comes to making adequate arrangements…for ammunition supply and care of the wounded,” he said. (Frost, loc. 3113, 66%)

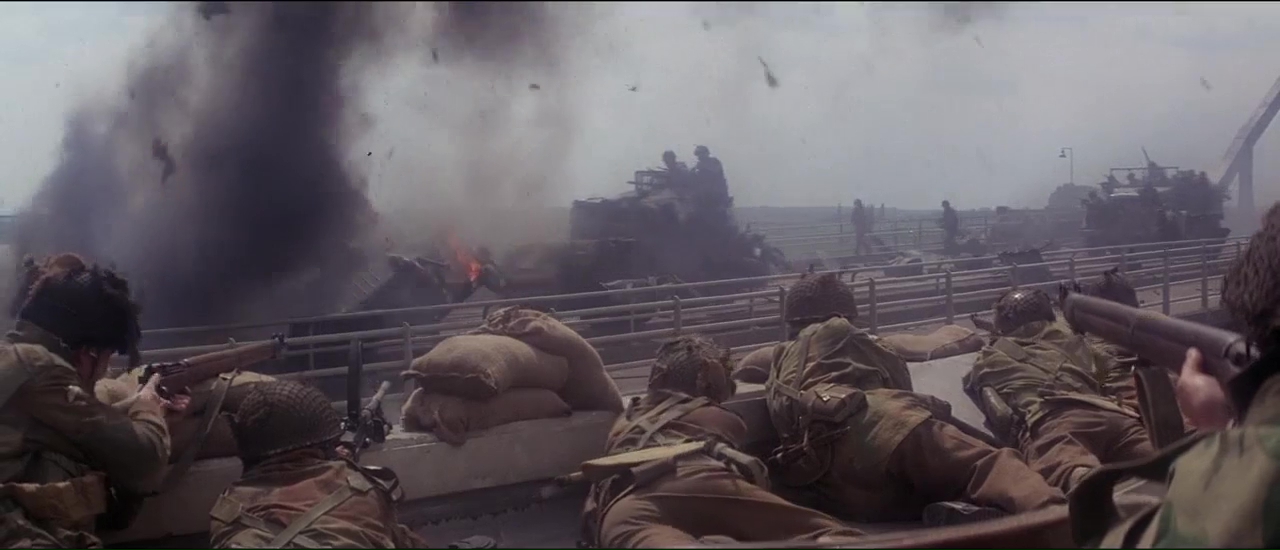

At about 0900 hrs on the morning of the 18th, the 9th SS Division’s reconnaissance unit (the 9th SS Aufklärungsabteilung), under SS Captain Viktor Gräbner, materialized on the bridge from the south.

Gräbner’s command comprised at least 22 vehicles, including Sd.Kfz 234 armored cars, Sd.Kfz 250 armored halftracks, trucks (reinforced with oil drums and sandbags), and other vehicles. (Marcel Zwarts, German Armored Units at Arnhem (Concord, 2003), pg. 11)

Frost and his men initially mistook them for friendly forces. In the buildings on the other side of the ramp were a detachment of airborne engineers under Captain Eric Mackay. The engineers watched amazed as the vanguard of German armored cars, with machine guns blazing away, tore through the British perimeter defences, and roared off into central Arnhem before the British could react. (Ryan, pg. 300)

The rest of Gräbner’s force drove into a hail of gunfire and explosions. (Zwarts, pg. 11)

In a two-hour battle, the British destroyed, damaged or disabled eight Sd.Kfz 250s, one Sd.Kfz 10, six trucks, and two field cars, and killed over 70 Germans, including Gräbner (whose body was never found). The British victory, however, was achieved at a heavy cost in ammunition which later impacted Frost’s ability to hold the bridgehead.

Each British paratrooper rifleman, armed with the bolt-action Lee-Enfield SMLE .303 Mk IV, was supplied with 100 rounds of ammunition. Section leaders and co-leaders were usually armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal). Each soldier with a Sten was normally provided eight magazines, each with 32 rounds (representing a total of 256 rounds). Bren light machine gunners were provided 24 magazines, each with 30 rounds (720 rounds). (Buckley & Preston-Hough, loc. 3750, 47%)

The British, however, would use captured German weapons. The Stens could fire the German 9 mm parabellum round used in the German MP40 submachine gun. No other German small-arms ammunition was compatible with British weaponry.

While it is unclear how much extra ammunition the paratroopers had managed to obtain before the battle, it was soon apparent to Frost that the battalion had expended the bulk of its ammunition in the battle.

“Throughout the rest of the day, small bodies of the enemy continued to attack the edge of our positions and shortage of ammunition began to tell,” Frost said. (Frost, loc. 3506, 74%)

That same evening, the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) issued the ammunition reserve. (Ibid, loc. 3800, 48%)

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean