The 8nd Airborne and a Narrow Run Thing

“I charge you all – put us down in Holland or put us down in hell, but put us down all in one place or I will hound you to your graves.” – Lt. Colonel Louis Mendez, 3/508 PIR

As Brigadier General Gavin stood in the doorway of his C-47, laden with 70 pounds of equipment, including an M1 Garand semi-automatic rifle, preparing to jump into the Nijmegen sector with other units of the 82nd Airborne Division, he contemplated the nature of his mission.

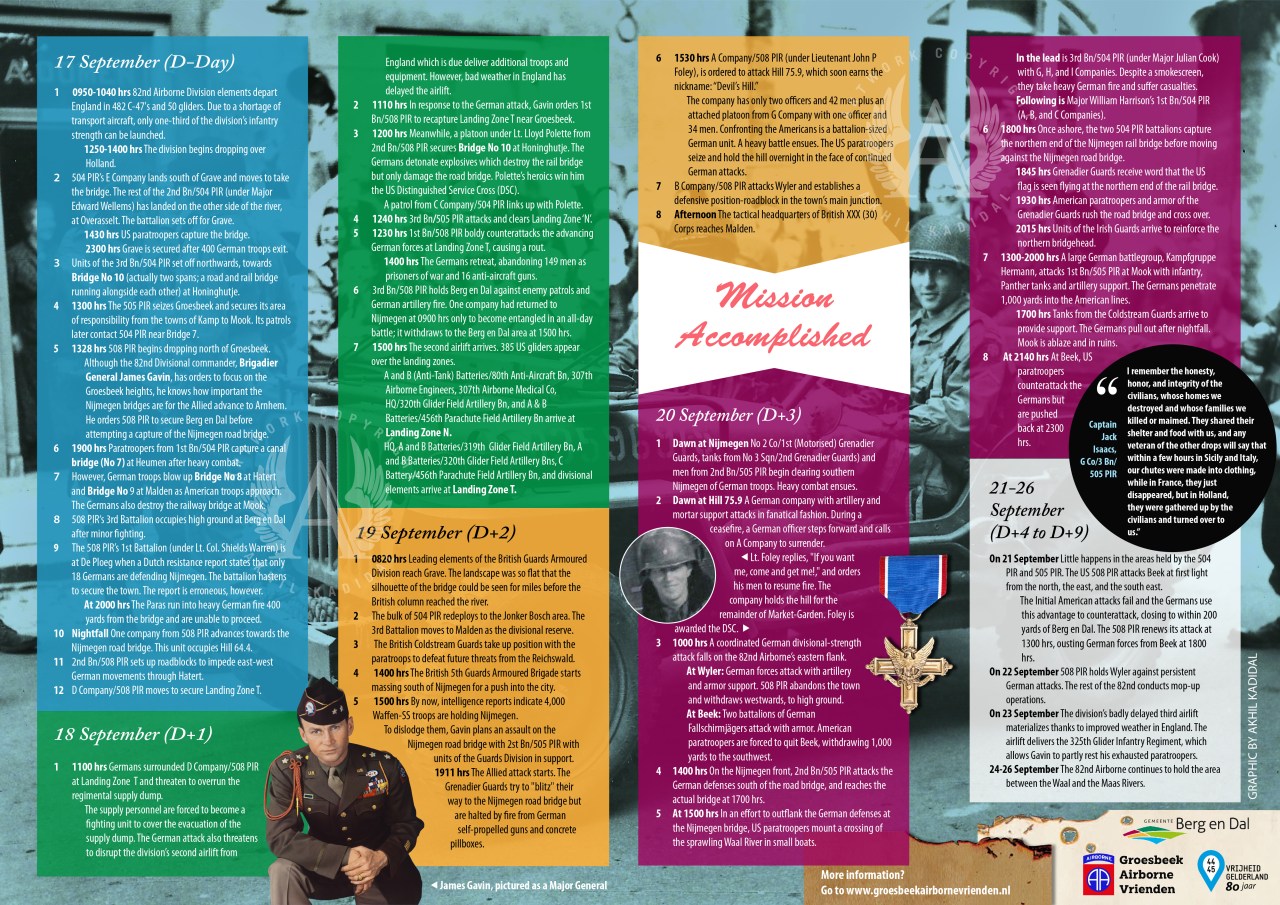

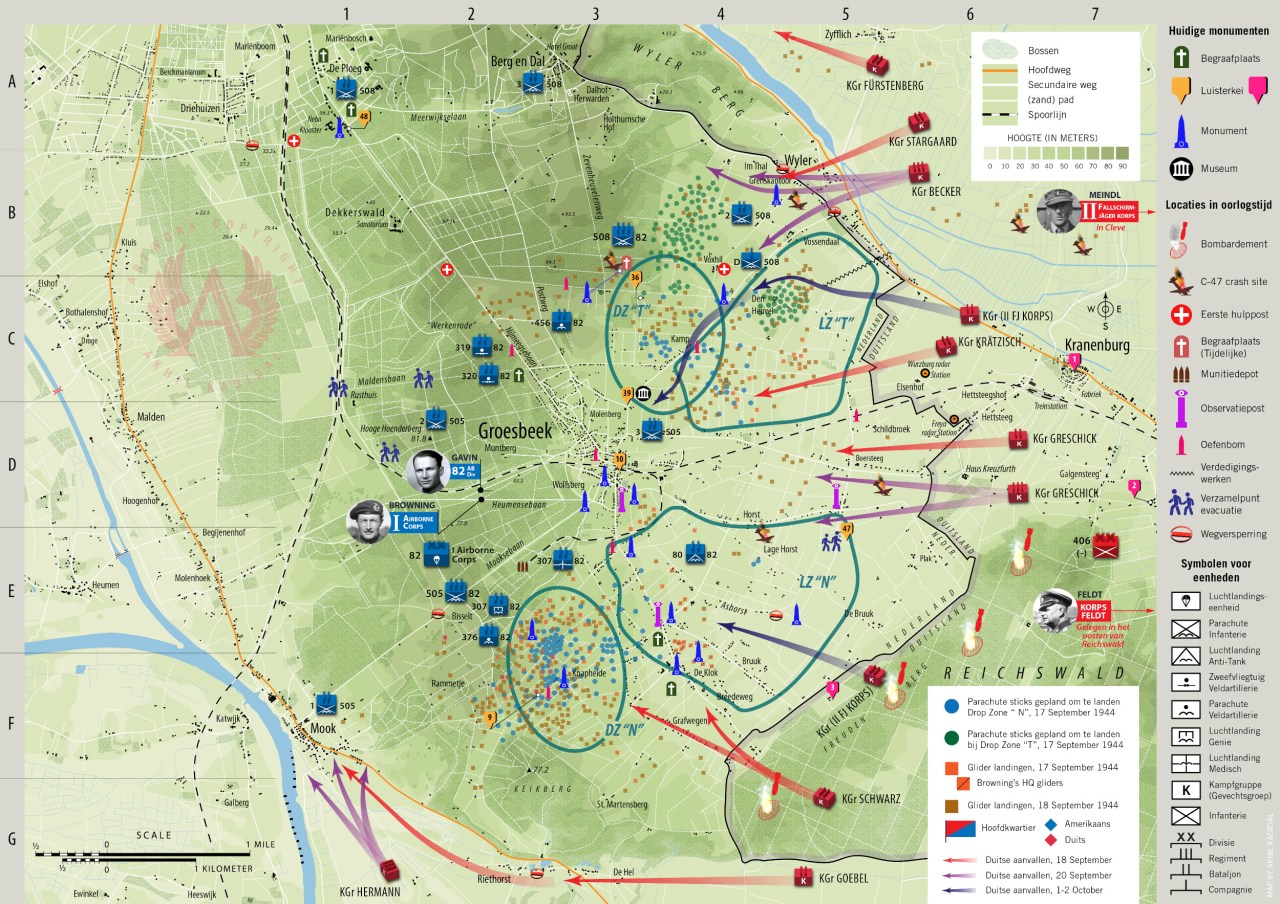

The 82nd Airborne’s mission lay at the physical center of the operation, between Arnhem and Eindhoven. In Gavin’s hands, the division (known as the “All Americans”) was to secure the high ground near the Dutch town of Groesbeek, to protect the landing zones for the balance of divisional troops expected in the following 48 hours.

Groesbeek lay at the foot of some of the highest ground in the Netherlands, which radiated northwards, towards Nijmegen and the German border, which (at its closest) was less than two miles away. In this zone of closeness was Germany’s Reichswald forest which was thought to hold German tanks. For this reason, the 82nd Airborne was going in with eight 57mm anti-tank guns of A Battery (80th Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Battalion). The guns and their gunners would arrive in 22 gliders. (WSEG Staff Study No. 3, pg. 101)

In reality, no German tanks existed in the Reichswald. However, there did exist a number of rear-echelon German troops from the Sixth Military District (Wehrkreis VI).

These troops were made up of convalescents, new recruits, instructors, men on leave, and garrison personnel, including aging World War I veterans. The assorted force belonged to Korps Feldt (a collection of rear area and training units under General Kurt Feldt) and its subordinate unit, the 406th Zur Besonderen Verwendung (ZBV, Special Purpose) Division. The 406th Division directly commanded 6,669 of the second and third-rate troops who were strung out across small camps from Kleve to Kaltenkirchen. (Buckley & Preston-Hough, Ch.6, loc. 2844, 36%)

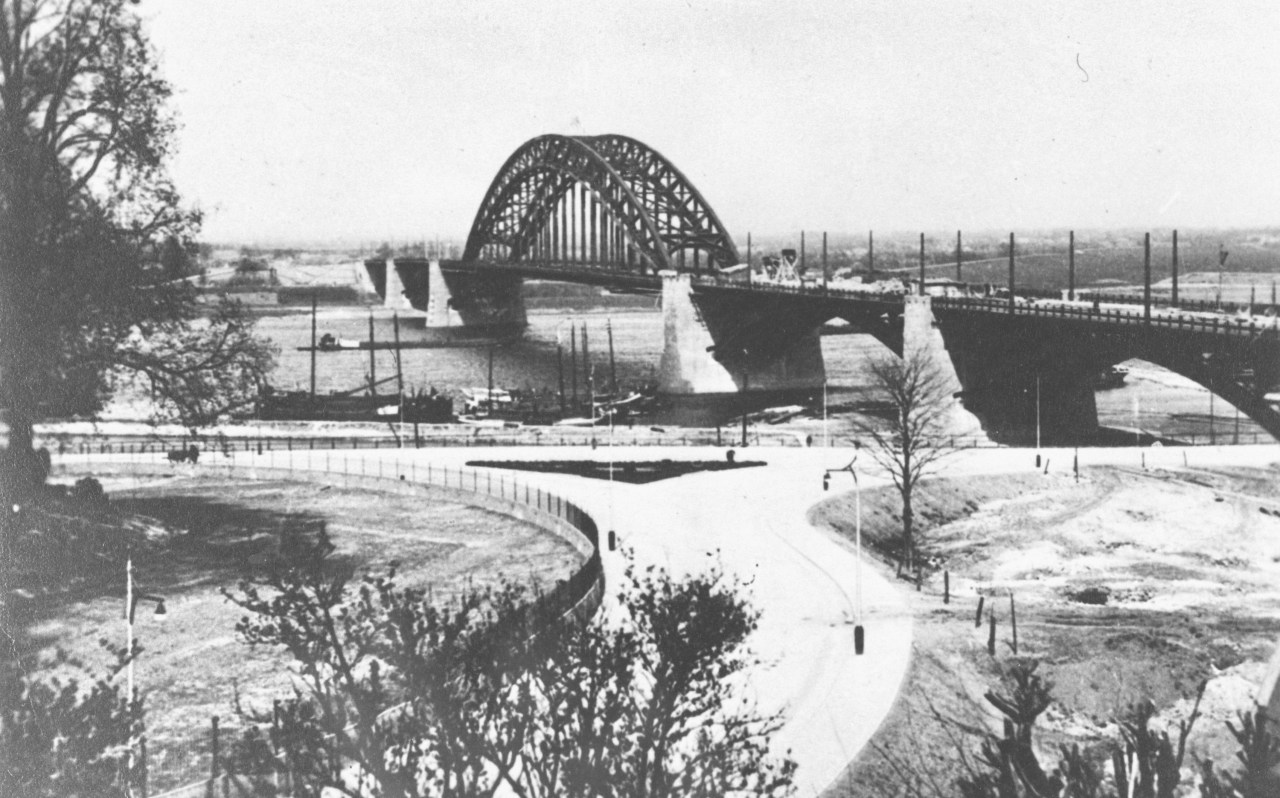

The 82nd Airborne also had to capture the main road bridge and the railway bridge at Nijmegen, a millenia-old factory and university town, to enable the Horrocks’ XXX (30) Corps to advance to Arnhem.

Nijmegen, a city of about 100,000 people, was dominated by six major roads leading out of a massive roundabout in the centre of the town. One of the roads led to a second roundabout south of the road bridge, a majestic structure spanning the fast-moving Waal river.

The bridge linked southern Holland with Arnhem and the north. Dominating this area of the city was an ancient fort called the Valkhof. Nearby was Hunner Park, a flower garden. (Nigel Nicolson and Patrick Forbes, The Grenadier Guards in the war of 1939-1945, Volume 1 (Gale & Polden, 1949), pg. 124)

The railway bridge was about half a mile downstream.

The Americans, however, would soon discover that rear-echelon units of the 406th Division had occupied the southern approaches to the bridge and Hunner Park. Many of the Germans had little combat experience. This would not diminish their value as fighting troops when the shooting began. By the morning of the 18th, they would be reinforced by units of the 10th SS Panzer Division.

Other critical objectives included one long river bridge at Grave and at least one of four bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal. In all, the division had to secure a 25 square-mile perimeter.

During the planning for the operation, the 82nd Airborne’s chief of staff, Colonel Robert H Wienecke complained that the division’s mission area was more appropriate for two airborne divisions.19

But “there it is – and we’re going to do it with one,” Gavin had said. (John C McManus, September Hope (Penguin, 2013), pg. 12-13)

Gavin, Golden boy

Gavin’s rise to command of the “All Americans” had been meteoric. With a reputation as a man who always “wanted to be where ‘the action” was, Gavin so impressed the 82nd’s original commander, Ridgeway, that he became assistant division commander in December 1943 and jumped into Normandy in this capacity. (McManus, ibid.)

When Ridgeway was promoted to lead XVIII Airborne Corps, Gavin became divisional commander of the 82nd Airborne (on 26 August 1944) but with the relatively junior rank of Brigadier General and no assistant commander to back him up.

But Gavin had a fierce determination to succeed, stemming from his childhood, when he had been orphaned to a New York City convent at the age of two. He was eventually adopted in 1909 (two years later), and grew up in the Pennsylvania coal town of Mount Carmel. All he knew as a child was familial dysfunction, poverty and privations.

At age 17, he joined the army as a Buck private and began a meteoric rise through the ranks. (McManus, pg. 10-11; “Out of the Ranks to a Three-Star Job,” LIFE (20 January 1958), pg. 22)

Although 37 years old in 1944, he resembled a man in his mid-twenties: tall, slim and athletic; handsome, with a chiseled, baby face that had narrow cheekbones and a lean nose.

He exuded confidence and his men gave him such nicknames as “Slim Jim” and “The Jumping General” (for his propensity to jump with his men straight into combat). Women found him attractive to the point that he had a reputation as a womanizer.

But if this gives the impression that Gavin was some kind of callous lothario, that would be erroneous. Gavin had a sensitivity that was almost uncharacteristic of professional soldiers in command of a division.

Once, during the battle, Ridgeway had come into Gavin’s command post (CP) and finding him absent (Gavin was at the frontline) had left a letter “demanding an immediate explanation.” This act, which may seem relatively minor to us over eight decades later, would so wound Gavin that he would ask to quit the division.

Writing in his diary at the time, Gavin said:

I know airborne operations as well as anyone in our service. I have been very lucky. Four combat jumps are a lot. I am ready to leave the service and try my hand at something new. I care not what. The only thing against this is a means of livelihood. I can fare reasonably well on what retirement I have earned. In the meantime, I’ll try anything. Whatever it is, I want to get completely away from the army and war. This letter of Gen. Ridgeway epitomizes all that I have never liked about our army. After 20 years of service, the past three years as a parachutist, the year and a half in combat with this division, to have successfully undertaken an extremely difficult combat mission, then to be sent a letter by my corps commander asking for an immediate explanation in writing why I flagrantly violated the tenets of military courtesy during the heat of combat upon the occasion of a visit to my CP. He has not seen fit to make any remark, good or bad, on our battle. And, worst of all, I was extremely considerate and courteous and always have been. Time to get out of his outfit. Perhaps the army too.

(Sorley, pg. 256-257)

But Gavin was not relieved of command. In October 1944, for his talents, Gavin was promoted to become America’s youngest Major General since George Armstrong Custer.

In the Nijmegen area, the 82nd Airborne Division would begin day one with 7,444 troops (out of an estimated total divisional strength of 11,994). Unlike Urquhart’s British 1st Airborne, most of the first wave in the 82nd Airborne were battle-hardened paratroopers, accompanied by a handful of artillery men and support personnel such as signalers and engineers.20

Confused Orders

But the 82nd was hobbled. Hazy orders from Browning’s I Airborne Corps headquarters appeared to prioritize the capture of the Groesbeek heights (to protect the division’s landing zones), instead of the bridges at Nijmegen which were vital to XXX Corps.

In its orders to the 82nd Airborne, British I Airborne Corps described the capture of the heights as being “imperative” to holding the bridges in the area. (21st Army Group, pg. 104) Browning feared that the Germans would deploy artillery on the heights and limit movement throughout Nijmegen.

He told Gavin: “Although every effort should be made to affect the capture of the Grave and Nijmegen bridges, it is essential that you capture the Groesbeek ridge and hold it.” (McManus, pg. 64)

While Gavin did not push back against this, he separately told Colonel Roy Lindquist, commander of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), that although the regiment’s primary mission was to hold the high ground at Berg en Dal near Groesbeek, he was also to send his 1st Battalion into Nijmegen to take the road bridge.

Lindquist, however, was confused about how to hold Berg en Dal while simultaneously making for the bridge. He did not clarify the matter with Gavin and instead assumed that he was to try to capture the bridge after the high ground had been secured. (McManus, pg. 64)

The flawed arrangement would rob the Allies of a chance to secure the bridges within 24 hours of landing. The 82nd Airborne also had too few troops in the first 48 hours to adequately hold all of its far-flung objectives.

Gavin was also hobbled by the presence of about 900 US glider pilots who were untrained for combat – unlike British glider pilots who were trained to fight as infantry. (Allied Airborne Operations in Holland; pg. 22)

The 504th PIR had the task of secure at least one of the four canal bridges and the key bridge at Grave town. The 505th PIR landed around Groesbeek. The 508th PIR would drop north of Groesbeek at 1328 hrs. A post-action divisional history would record that the “drop patterns were excellent.” (A Graphic History of the 82nd Airborne Division (US Army/SHAEF, 1945), pg. 4)

In fact, the accuracy of the airborne landings in all three sectors (Arnhem, Nijmegen and Eindhoven) would dispel the notion that daylight operations over enemy territory, heavily defended by flak, can be “excessively hazardous”.

“Market has proven this view erroneous,” wrote General Brereton in his after-action report. “The great dividends in accuracy of drop and landing, and in quick assembly of troops which may be had from daylight operations were enjoyed to the full.” (See Narrative of Operation Market (US Army, 14 July 1945))

Capturing the Grave and Canal bridges

The 504th PIR had previously fought in Sicily and Italy in 1943, but had been bled white in those battles and had thus unable to participate in the Normandy campaign.

Now, the regiment was back in action. Its E Company (of the 2nd Battalion) landed south of Grave and moved to take the Grave bridge from the west. The rest of the 2nd Battalion, under Major Edward Wellems, landed on the other side of the river, at Overasselt, and set off to take the bridge from the east. This was, after all, the only way to capture bridges – from both sides.

The Grave bridge over the Maas river was of vital importance as it spanned 800 feet of water that could not be easily crossed if the bridge was blown up. However, the US paratroopers captured the bridge at about 1430 hrs and then secured Grave town after the 400-strong German garrison fled.

Meanwhile, units of the 3rd Battalion (504th PIR) set off northwards, towards Bridge No 10 (actually two spans; a road and rail bridge running alongside each other) at Honinghutje. Meanwhile, the 505th PIR seized Groesbeek town at 1300 hrs and secured its area of responsibility from the towns of Kamp to Mook.

At 1900 hrs paratroopers from 1st Battalion (504th PIR) succeeded in capturing a canal bridge (No 7) at Heumen after heavy combat. The bridge was a lock that rose up to allow boats and barges to go through.

However, German troops blew up all the other canal bridges in the area and badly damaged bridge 10, elevating the US capture of the Heumen bridge.

Erroneous information

On the Groesbeek-Nijmegen road, the 508th PIR’s 1st Battalion (under Lt. Colonel Shields Warren) was at De Ploeg, settling in for the night when a Dutch resistance report arrived, claiming that only 18 Germans were defending Nijmegen.

The regimental commander, Lindquist, ordered Shields to seize the Nijmegen road bridge. (McManus, pg. 157)

The report was false. At 2000 hrs, heavy German fire 400 yards from the bridge brought Shields’ battalion to a dead stop. This was the result of hundreds of German troops pouring into the 82nd Airborne’s area hours after the landing.

Among the German units rushed to the 82nd Airborne’s area was the 39th Grenadier Replacement and Training Battalion, which despite being located 110 kms from Nijmegen, was battling US paratroopers six hours later. (Buckey & Preston-Hough, Ch. 6, loc. 2870, 36%)

In their after-action report, the 82nd Airborne command staff noted that the Germans had about eight battalions-worth of troops in the sector.

“Enemy reaction was prompt and appeared to follow a definite pattern,” the report said. “All local [German] troops were committed immediately in ‘piecemeal’ fashion. Nearby homeguard-type troops were thrown in as quickly as they could be rushed to the operational area.” (A Graphic History of the 82nd Airborne Division, pg. 3)

In fact, the Germans moved with stunning alacrity to fight the Allied airborne in all sectors.

Shield’s A and B Companies, in Nijmegen, were also confronted by members of a 750-man Kampfgruppe which bore the name of its commander, Oberst (Colonel) Henke. (McManus, pg. 162; Kershaw, pg. 99)

Within Kampfgruppe Henke was 1st/6th Home Defence Training Battalion (with three companies, composed of WWI veterans and overage reservists)21, plus a company of the Hermann Goering Training Regiment, and an Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO) school already operating as a security detachment at the Nijmegen road bridge. (Buckey & preston-Hough, Ch. 6, locs. 2892-2899, 37%; Kershaw, pg. 99)

These untried troops would fiercely resist Shield’s men and subsequent American efforts to take the bridge, with one historian describing German resistance as “severe”. (Phil Nordyke, All American, All the Way, Zenith Press, 2010; pg. 78)

The fighting spirit of such ersatz forces at the bridge would be emblematic of the role played by poorly equipped rear-echelon German troops in frustrating the ambitions of the 82nd Airborne.

Distracting the Airborne

At mid-morning on the following day, 18 September, six German battle groups from the 406th Division attacked from out of the German border. Their objective was to overrun the landing and drop zones and reclaim Groesbeek. The attackers were again second or third-rate personnel from training and replacement units, battalions with “stomach and ear” personnel (infirmary cases), and Luftwaffe men from defunct NCO schools.

The Germans, attacking from the direction of the German town of Kranenburg, ejected a US 508th PIR platoon from the German village of Wyler. By 1100 hrs, had surrounded the 508th PIR’s D Company which was protecting the regimental supply dump. American supply clerks had to become a fighting unit to cover the evacuation of the dump.

The German attack also partly overran Landing Zone T where the 82nd Airborne second airlift was scheduled to arrive at 1200 hrs.

To his relief, Gavin learned that bad weather in England had delayed the second airlift. At 1110 hrs, the 1st Battalion (508th PIR) and the regiment’s G Company went into action, to recapture LZ T.

The Germans, some of whom were untrained recruits or aging World War I veterans, were no match for the elite paratroopers who in many cases, went after them with fixed bayonets. By 1400 hrs, the Germans were in retreat, abandoning 149 of their own as prisoners of war (POWs). The Germans also left behind 16 anti-aircraft guns. Further south, 1st Bn/505 PIR was counterattacking eastwards and clearing LZ N.

Around 1500 hrs, amid diminished small-arms and artillery fire, the second airlift, with 429 gliders arrived.

They carried three artillery battalions (319th & 320th Glider Field Artillery, 456th Parachute Field Artillery), the balance of the 80th Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Battalion, the division medical company (307th Airborne Medical Co), plus 177 vehicles (mostly jeeps) for the parachute infantry, division headquarters and signals, according to Gavin. (James Gavin, Airborne Warfare (1947), 61%)

Casualties were light and Gavin was pleased that he had 1,650 additional personnel with their weapons, tools, and vehicles to strengthen his perimeter. At the same time, he was also aware that nearly all of the new arrivals were support forces. In the meantime, every available combat trooper was required to hold the frontline which now stretched from Mook (in the south) to Groesbeek (in the center) to Wyler and Beek (in the north).

As the day went on “the German attacks were increasing in extent, intensity, and duration,” Gavin said. (Airborne Warfare, 61%)

While the attacks by the rear-echelon troops of the German 406th Division did not make a major dent in the 82nd Airborne’s lines, they preoccupied the “All Americans” long enough to buy time for units of the 10th SS Panzer Division to reinforce Nijmegen.

This would delay the fall of the city and capture of its bridges to 20 September.

Capturing the Nijmegen Bridge

By the afternoon of 19 September, Dutch resistance and US intelligence estimated German troop numbers at Nijmegen at about 4,000. This included about 500 “top-quality” Waffen-SS troops of Kampfgruppe Euling, which commanded the road bridge. The SS were supported by an 88mm gun on the traffic circle, backed by four 47mm guns, a 37mm gun, and mortars in Hunner Park. (Kershaw, pg. 194)

Postwar discourse sometimes blames the 82nd Airborne for not seizing the Nijmegen bridges in the first 48 hours. In reality, the “All Americans” never had a chance of taking the bridges on their own without the help of the Guards Division. And the Guards only reached Nijmegen on the afternoon of the 19th (which was D+2).

Such was the scale of German resistance at Nijmegen that Guardsmen also had to pay a heavy price in lives to secure local objectives, despite wielding a sizable number of tanks and other heavy weapons. A preliminary airstrike by British Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers at Nijmegen at 1530 hrs did not dissuade the German defenders, who fought fiercely. (The Grenadier Guards, pg. 195)

The Guards attacked along three prongs (towards the Nijmegen post office, towards the rail bridge, and towards the road bridge). At least 20 Guards Sherman tanks went into battle, American paratroopers riding on the hull.

Several British Sherman tanks were hit and one was blown up as they approached Hunner Park. The paratroopers also suffered casualties before the Allied Generals called off the attack as night fell.

Allied units in the Nijmegen battle, 19-20 September

| Objective | Allied units involved in the attack |

|---|---|

| The Post Office attackers, 19 September (under British Major G Thorne) | – Two platoons from No 3 Company, 1st Grenadier Guards – One tank troop under Lt. James W Scott from No 1 Squadron, 2nd (Armoured) Grenadier Guards -One platoon of US paras picked at random from road by Gavin |

| Western Force (units headed for the rail bridge), 19 September (under British Captain J W Neville) | – D Company (Captain Taylor Smith) of 505th PIR – One motorised platoon under Lt. J C Moller from No 3 Company, 1st Grenadier Guards – One tank troop under Lt. G R Merton from No 2 Squadron22 of the 2nd (Armoured) Grenadier Guards |

| Eastern Force (units headed for the road bridge), 19 September (under US Lt. Colonel Ben Vandervoort) | – E, F & HQ Companies of 2nd Battalion, 505th PIR (Lt. Colonel Ben Vandervoort) – Three platoons from No 2 Company (Captain The Duke of Rutland) of the 1st Grenadier Gds, minus one motor platoon and one carrier section – Three tank troops from No 3 Squadron (Major Alexander M H Gregory-Hood), 2nd (Armoured) Grenadier Guards |

| Capture of the Nijmegen road bridge, 20 September | – HQ, E and F Companies of 2nd Battalion, 505th PIR – Three platoons of No 2 Company, 1st Grenadier Gds, minus one motor platoon and one carrier section – Three tank troops from No 3 Squadron, 2nd (Armoured) Grenadier Guards – No 4 Company, 1st Grenadier Guards – King’s Company, 1st Grenadier Guards |

German units at Nijmegen, 19-20 September

| Unit | Commanders | Location | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kampfgruppe Henke (Oberst Henke of Fallschirmjäger-Lehr Stab 1) | |||

| Kampfgruppe Runge | SS Sturmbannführer Otto Runge | Around rail bridge | SS Junkerschule, three companies of 6th Ersatz und Ausbildungs Bataillon, and elements of 406th Division |

| Kampfgruppe Melitz | Luftwaffe Major Melitz | Inner city between the railway bridge and the road bridge | 4. and 5 Kompanie, 14. Schiffstamm Abteilung, 4. Batterie, Schwere Flak Abteilung 572 and a Flak Ersatz Abteilung |

| Fallschirmjäger Ersatz und Ausbildungs Regiment “Hermann Göring” | Major Ahlhorn | Southern approach to the road bridge and Valkhof | Elements of Grenadier Ersatz und Ausbildungs Bataillon 365 |

| 10th SS Panzer Division units | |||

| 1. Kompanie (10th SS Panzer Pionier Abteilung) | SS Untersturmführer Werner Baumgärtel | Hunner Park | |

| Kampfgruppe Euling | SS Hauptsturmführer Karl-Heinz Euling | Hunner Park | II. Bataillon of the 19th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment |

| Kampfgruppe Reinhold | SS Sturmbannführer Leo Reinhold | Lent, north of the road bridge | II. Abteilung of 10th SS Panzer Regiment (no tanks) |

The Waal Crossing

Meanwhile, the Allied Generals had decided to also capture the north bank of the road bridge. Major Julian Cook’s 3rd Battalion (504th PIR) was assigned to conduct a crossing of the river Waal in flimsy, canvas boats, in broad daylight, on the afternoon of the 20th.

As the paratroopers rowed through the wide, fast-moving Waal towards the German-held northern bank, heavy fire rushed down at them, past a whirling smokescreen laid by British tanks on the south shore. German conscripts on the north bank mercilessly raked the first wave of boats (roughly carrying about 390 paratroopers), killing about 48 and wounding about 160 others. (see Margry)

British officers watching the scene from the safety of the south bank were in awe of the action transpiring on the river and the far shore. Lt. Colonel Giles Vandeleur of the Irish Guards, watching through binoculars, saw none of the surviving paratroopers waver after reaching the north bank.

Only the dead or the wounded fell; not a man unscathed failed to rush the Germans. “My God, what a courageous sight it was,” Vandeleur said. (Gavin, pg. 179)

Browning turned to Horrocks and said: “I have never seen a more gallant action.” (ibid.)

Waal River Crossers, 504th PIR, 20 September 1944

| Wave | Time (hours) | Unit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1457 | H and I Companies, plus 3rd Battalion staff | 26 boats in the first wave; 13 sunk |

| Second | 1515 | G Co, 3rd Bn HQ & HQ Company | 13 boats available |

| Third | 1530 | C Company | |

| Fourth | 1600 | A Company | |

| Fifth | 1700 | 1st Bn HQ and HQ Company | |

| Sixth | 1900 | B Company |

What none of the observers could see was the brutal hand-to-hand combat which ensued on the north shore. The American survivors were in such a murderous rage that after spilling ashore on the north bank they killed every German they found – even 15-year-old conscripts and senior citizens who had been exempted from service earlier in the war – even those trying to surrender. (Margry, Vol 2, Part IV, 68%; Kershaw, pg. 197)

The American seizure of the north bank imperiled German chances of holding on to the bridge. Although the Germans had prepared the bridge for destruction, Model had ordered Harmel and Bittrich not to detonate the charges because he thought the bridge would be useful for a counterattack. Harmel and Bittrich thought this was madness. (Kershaw, pg 193)

When armor and infantry of the Guards Division began to cross the bridge, Harmel decided to blow the bridge. To his shock, he discovered that the charges would not blow.

Jan van Hoof

In one of those legends that often emerges in war, there grew a rumor of unexpected heroism, of a 22-year-old student and resistance member named Jan van Hoof who had sneaked onto the bridge to cut several cables, including key wires leading to the demolition chamber, saving the bridge from destruction.

There was no evidence that van Hoof had saved the bridge, except that he had excitedly told his sister on the afternoon of the 18th that the “bridge is safe.” Later, his parents also found a pair of insulated pliers in the overalls that he had worn on the morning of the 18th.

The van Hoof was brave, even heroic, is indisputable. He was killed on 19 September while acting as a guide for a British Humber armored scout car. Wearing a Dutch helmet and an orange armband that identified him as a member of the resistance, van Hoof sat on the armored car’s mudguard, in the open.

A German 20mm gun destroyed the Humber, killing the two British soldiers inside. Affected by the concussion of the blast or perhaps even wounded, van Hoof jumped from the vehicle.

When Germans called out to him to surrender, he shouted: “Dutchman, Free Netherlands!,” before collapsing.

German troops ran up to him, pulled him away and seeing his orange Dutch resistance armband, began to pummel him. Then they put a bullet through his head. (Margry, Vol 2, Part IV, 50%)

A three-year Dutch government inquiry, conducted from 1949 to 1951, investigating the saving of the bridge gave van Hoof the benefit of the doubt, although the matter remains controversial.

The fact is that the Germans tried to blow the bridge under the impression that their mechanisms, circuits, and cables for demolition were intact. That these mechanisms had been disrupted can only be attributed to another party.

Whatever or whomever the cause, the magnificent bridge remains standing to this day.

Rage against the Guards

The Germans had lost the Nijmegen road bridge. The way was open to Arnhem. But to the utter disbelief of the American airborne, they watched the Guards halt for the night on the north bank.

The commander of the 504th PIR, Colonel Reuben Tucker, was livid. Tucker had crossed the river in the fourth wave. He had seen the losses suffered by his men. But the thought that the Guards were not even ready to exert themselves to save the lives of their own countrymen at Arnhem, enraged him.

“Your boys are hurting up there at Arnhem,” he said to a Guards major. “You’d better go. It’s only 11 miles.”

The British Major responded that the British tanks could not proceed until their infantry caught up with them. Tucker was incoherent with rage. His radio dispatches to Gavin were laced with profanity against the Guards. (Gavin, pgs. 181-182)

“We had killed ourselves crossing the Waal to grab the north end of the bridge,” Tucker wrote later. “[And the British were tucking] in for the night, failing to take advantage of the situation.” (Ryan, pg. 421)

Gavin later complained to Horrocks that the actions of the Guards on the north bank of the bridge had “bitterly disappointed” the 82nd Airborne. Gavin insisted that the British should have immediately sent a “task force” straight for Arnhem Bridge.

“In fact, at the time, [Gavin] felt that the British had let them down badly,” Horrocks later wrote in his diplomatic memoir, Corps Commander. (Horrocks, pg. 154)

He added that Gavin had no clue of the traffic chaos which had erupted at Nijmegen, which was still a battlefield. However, Horrocks also admitted that he was also concerned about the fate of his armor.

“The country in front between Nijmegen and Arnhem, which we called the Island, was almost impassable for tanks; all the narrow roads ran along the tops of embankments, with wide ditches on either side, and any vehicle on an embankment was a sitting duck for the German anti-tank gunners hidden in the orchards with which the Island abounded: one knocked-out vehicle could block a road for hours,” he wrote. (Horrocks, pg. 154)

But a daring armored task force racing forward at night might have traversed the island by dawn to reach Arnhem bridge.

Tucker thought of sending the 504th PIR into the night but dismissed the idea because the regiment was at less than half strength and almost out of ammunition. (Ryan, pg. 421-422)

The British 1st Airborne was once again on its own.

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean