The US 101st Airborne’s Frontier War

“That cannot be. It never snows in September.” – German soldier watching panorama of Allied parachutes from a distance

The 101st Airborne Division, meanwhile, had dropped south of the 82nd and just north of the Dutch city of Eindhoven.

The initial Market plan spread the 101st Airborne (known as the “Screaming Eagles”) across seven drop zones, to secure a sprawling 30 mile-wide chunk of territory. The divisional commander, Major General Maxwell D Taylor, objected and the drop zones were more concentrated.

Nevertheless, the updated mission corridor was still 15 miles wide, which required the dispersion of the division in three areas, which would render the airborne troops weak at “every critical point”. Running through the wide corridor was Highway 69, the primary route of advance for Horrocks’ XXX Corps.

To keep it open would necessitate “the most vigorous shifting of troops to meet the numerous threats as they developed along this long corridor,” Taylor wrote in an after-action report. (Report of Airborne Phase (17-27 September 1944), Operation “Market,” 101st Airborne Division (SHAEF, 15 October 1944), pg. 1).

For Taylor, the mission was almost comparable to the Old American West, where isolated US Army garrisons had to contend with “sudden Indian attacks at any point along” routes of transit. (Charles B MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign (US Army Center of Military History, 1993), pg. 144)

The division’s orders stipulated the capture of at least four highway and railway bridges over the Aa River and the Zuid Willems Canal at Veghel (by the 501st PIR), a highway bridge over the Dommel River at St Oedenrode, another highway bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal, near the village of Son, and the capture of Eindhoven city and its bridges.

The 101st Airborne at Arnhem?

But the division almost never received this particular mission.

The initial draft of the Market plan had the US 101st Airborne Division dropping at Arnhem, with the British 1st Airborne landing in the Eindhoven sector. However, the British 1st Airborne asked to be assigned to Arnhem because it was familiar with the terrain through planning for an earlier operation. (Urquhart, pg. 19).

One can only speculate now as to what the results would have been if the “Screaming Eagles” had been assigned to Arnhem.

Roy Urquhart later wrote that London’s relations with Washington would have taken a blow had a US force, assigned to the apex objective of a British military operation, been stranded and destroyed due to the inability of the British Second Army to reach the sector within 48 hours as required. (Ibid., pg. 19)

However, it is possible that the “Screaming Eagles” would have prevailed at Arnhem until relieved. For one, Taylor would have absolutely refused to drop six miles from the target area, which could have led to the securing and fortification of Arnhem at divisional-level strength.

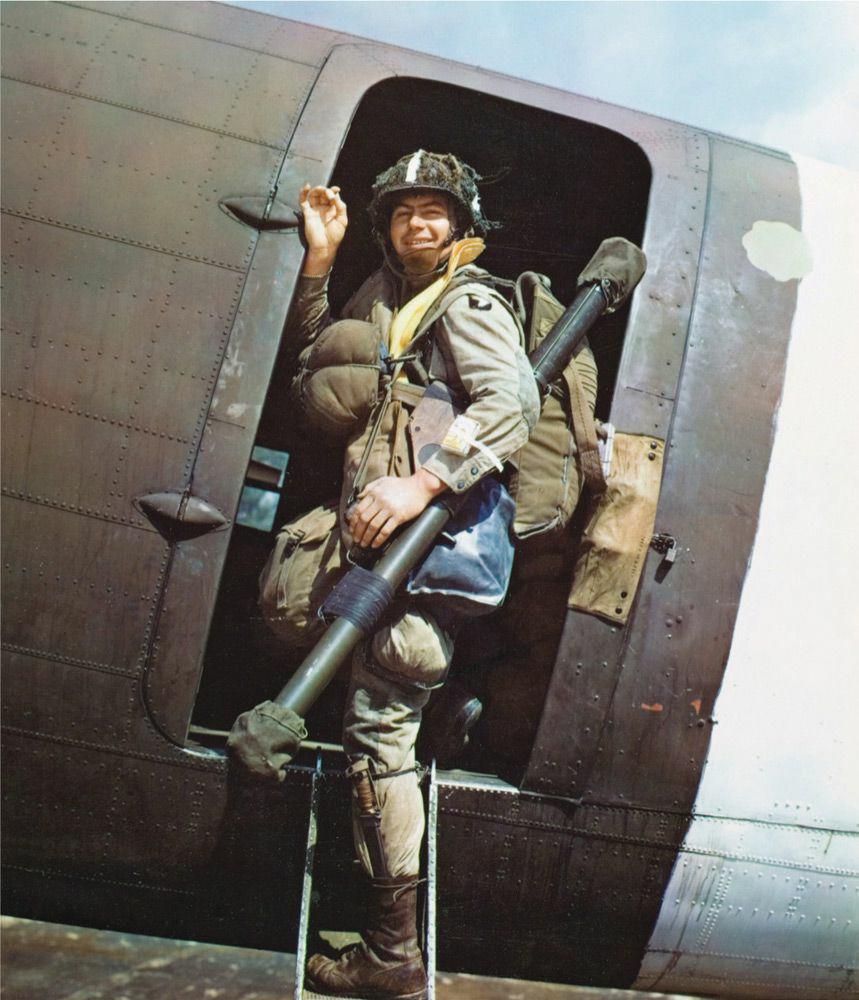

Also, the Americans were equipped with a preponderance of automatic and semi-automatic small-arms such the M1 Garand, the M1 Carbine, the Thompson submachine gun and the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), the latter of which had such penetrative power that its rounds were capable of punching through engine blocks. These weapons were better suited for the close- and medium-quartered combat which dominated battle in northwest Europe.

In contrast, a British para company was mostly made up of men armed with the bolt-action Lee-Enfield SMLE rifle, which could not match the volume of German firepower. The British paras compensated for this somewhat through precision shooting.

In Arnhem, for example, a German SS squad leader, Alfred Ringsdorf, 21, a veteran of the Russian front, was astonished by the proficiency of the British paratrooper with the rifle. “The British shooting was deadly,” Ringsdorf said. “We could hardly show ourselves. They aimed for the head and men began to fall beside me, each one with a small, neat hole through the forehead.” (Ryan, pg. 275)

US forces also possessed the 60mm M9/M9A1 bazooka hand-held anti-tank weapon, which was arguably more effective than the British hand-held anti-tank weapon, the PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) — In terms of handling, weight, loading, range, and penetration power.

US bazooka operators could have taken a higher toll on German armor and vehicles.

The 101st Airborne would later show its ability to endure a siege at Bastogne, during the Ardennes offensive in December 1944. In that battle, the division held its ground against superior German forces (including tank attacks) until relieved eight days later, thanks to adept leadership, its defensive tactics, and the terrain around the town. (For more, see S L A Marshall’s Bastogne: The First Eight Days)

Taylor was also an experienced airborne commander and would have exercised command in a more deft manner than Urquhart did. But one critical defect in Taylor’s authority was that his men saw him as somewhat remote. He neither achieved popularity within the division nor outside of it, as Gavin arguably did.

Many “Screaming Eagles” regarded Taylor as a man who regarded command of the division as a stepping stone to higher command.23

Nevertheless, in 1944, Taylor was backed up by a team of competent, charismatic leaders in the division, including his assistant commander, Brigadier General Gerald J Higgins, 34, and Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, 46, the divisional artillery commander who would later win plaudits for his leadership at Bastogne.

Maximum Force

As per the Market plan, the 101st was due to make contact with the British Guards Division within 24 hours of landing.

Therefore, Taylor was determined to start the first day with a maximum number of combat troops, rather than land with a preponderance of artillery, which he thought would be useless in supporting his far-flung forces. (MacDonald, pg. 144)

Consequently, when the “Screaming Eagles” landed on 17 September with 6,931 men, most of them were combat paratroopers. The primary DZ was a large heath north of Son (known as Zon before WWII) where the 502nd and the 506th PIRs landed, with another DZ near Veghel for the 501st PIR.

The fly-in to the Netherlands was nearly flawless. Despite German flak and small arms fire, only one pathfinder aircraft and two out of 424 aircraft with paratroopers failed to reach the drop zones. But then German flak at Schijndel and Hertogenbosch shot down 13 planes after the paratroopers dropped.

The paradrop itself was accurate; US casualties were light at 1.56%. (WSEG Staff Study No. 3, Table I & Table III, pgs. 73, 74) “The average time of assembly was about one hour for each battalion. All initial objectives were reached prior to darkness. Recovery of equipment averaged at 95%,” said the divisional initial after-action report. (101st Airborne Division: Report of Airborne Phase, pg. 1)

Dutch civilians in the Son area had a magnificent view of the arrival of the Screaming Eagles.

“It was 1300 hours in the afternoon. A faint drone seemed to fill the sky,” said one civilian, Pierre Drenters. “…As the sound grew louder, it was not the same sound we were used to hearing. We looked up. An armada of planes appeared over our area. They came in quite low. We feared an air strike and headed for the shelter. But these were not bombers. They were transport planes on some kind of a mission. Then a beautiful sight – literally hundreds of paratroopers spilled out from the planes.” (George Koskimaki, Hells’ Highway (Casemate, 2003), Ch. 4, 7%)

Trouble loomed for one airborne unit, Lt. Colonel Harry Kinnard Jr’s 1st Battalion of the 501st PIR, which missed its drop zone west of Veghel and landed three miles to the northwest, around Kasteel (Castle) Heeswijk. The battalion rallied and seized its objective, a road bridge over the Aa River after a strident, two-hour march.

German reaction to the arrival of the 101st was initially tepid. The Germans had less than 600 troops available near the US landing zones, plus a few tanks and 88mm guns. The 101st Airborne recorded “very little or no enemy opposition” at its DZs. (WSEG Report No. 3, pg. 67)

However, the division soon encountered setbacks. The Germans had blown nearly all the bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal days before the advent of the airborne landings. One bridge was still intact, just south of the village of Son. But as troopers from A Company (506th PIR) approached, the Germans blew up the crossing in their faces.

Two other bridges (a railway and a road crossing) were to the west, southeast of the Dutch town of Best. Although these bridges were not part of the 101st key objectives, the decision was made to try to secure them.

Lt. Colonel Robert Cole’s 3rd Battalion (502nd PIR) was given the task on the 17th. Cole sent Captain Robert Jones’ H Company to secure the road bridge but the company lost its way in the Sonsche forest and blundered into a small group of Germans who were soon reinforced by truck-borne infantry and heavy weapons from the direction of Hertogenbosch.

These units were potentially from German General Walter Poppe’s 59th Infantry Division, which was detraining at Tilburg, over 15 miles (24 kms) northwest of Best. The Americans were discovering first-hand how quickly the Germans could mobilize scattered troops and rapidly transfer them to the frontlines.

Urgent messages were coming in over the radio to Captain Jones, extolling him to get someone to the road bridge. Jones organized a reinforced patrol under Lt. Edward Wierzbowski24 to secure the bridge.

By dawn on the 18th, Wierzbowski and his men were overlooking the road bridge, which was over one hundred feet long, with a German barracks on the other, southside of the canal. The Germans spotted the Americans and opened fire across the water. The Americans had no way to get to the bridge. Hours later, as Wierzbowski watched, the Germans blew up the bridge in a massive explosion that showered debris across the area.

Lacking radio communications with the rest of the battalion, Wierzbowski had no way to inform his superiors that the bridge was gone. (Koskimaki, Ch. 10, 31%)

The 3rd Battalion (502nd PIR) was having its own problems. A German sniper had shot and killed the battalion commander, Cole (a popular figure among his men), demoralizing the unit.

By dawn on 19th, Wierzbowski and his men were still cut-off from the rest of the division. Soon, they were under heavy German attack and overrun – but not before one of their own (Private First Class Joe E Mann) lay down on a German grenade, saving the lives of others around him – an act which resulted in the award of a posthumous Medal of Honor (MoH). Incidentally, looking at US medal citations from the Vietnam War, roughly 60% of posthumous MoH awards were also given to men who threw themselves on enemy grenades.

Wierzbowski’s captive platoon was taken to a nearby aid station but they grabbed some weapons and returned to US lines “with a batch of prisoners”. (Mark Bando, 101st Airborne: The Screaming Eagles in World War II (Zenith Press, 2007), Ch 6, 46%)

The Germans Go After the Weak links

The destruction of the Wilhelmina Canal bridges delayed the advance of Horrocks’ XXX Corps while also delaying the capture of Eindhoven city by the 506th PIR until the morning of the 18th.

A British Army Bailey bridge was finally thrown over the crossing at Son on the night of 18/19 September.

Meanwhile, the paratroopers of the 506th PIR had made contact with advance units of the British Guards Division in the city by the afternoon of the 18th. With this link-up, they could almost believe that their part in the operation was over.

But not yet.

On the 19th, an estimated 3,000 new German troops backed by tanks of the powerful 107th Panzer Brigade struck the dispersed “Screaming Eagles” along Highway 69 (soon nicknamed “Hell’s Highway”).

Commanded by Major Berndt-Joachim Freiherr von Maltzahn, the fully mobile 107th Brigade was the most potent German armored force in the sector, with a tank battalion, a panzergrenadier battalion, and an armoured engineer company.

The brigade’s primary combat vehicles were: 36 Panther tanks and 11 Panzerjäger IVs. The brigade also had over 100 halftracks (of which four were equipped with 80mm grenade-launchers; four had flamethrowers; ten had a 75mm howitzer each and about 42 had tri-machine gun mounts. Two halftracks each towed a six-barrelled Nebelwerfer mortar and eight had 120mm mortars. (Margry, Vol 2, Ch. 2, 54%)

The German had been quick to realize the domino-like vulnerability of Market-Garden – hitting and severing the British advance over Highway 69, the corridor of life, would collapse the Allied venture. The Germans focused their attacks on the Bailey bridge at Son, Koevering, and Veghel to disrupt British movement over the highway.

US casualties began to rise. By D+5, the 101st was in battle with over 8,000 German troops. Bolstered by British armor and heavy weapons, the 101st kept their “frontier war” going, to keep “Hell’s Highway” open.

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean