Point of No Return

“The Red Devils and the Polish paratroopers can do anything” – Lt. General “Boy” Browning

By the 18th, while the US airborne divisions were inching towards securing their objectives, the odds were mounting against the British 1st Airborne Division.

Even as Frost and his men tenaciously held on at Arnhem bridge, things were less than stellar in the British sector. Before dawn, a large German battlegroup, Kampfgruppe Tettau (under Lt General Hans von Tettau), which included the 224th Panzer Company (equipped with old but dangerous French Renault tanks) moved against 1st Airlanding Brigade at Renkum on 18 September.

A fierce all-day battle erupted that had consequences for Brigadier Shan Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade which began to drop over DZ Y at Ginkel Heath that same afternoon. Heavy German fire began to shoot up at Hackett’s troops as they hung helplessly in mid-air.

Before the drop, in one C-47, some of the paratroops, possibly from the 10th Para Battalion had been cheerfully talking about winning the battle to come and ending the war by Christmas. (Martin Middlebrook, pg. 226) Now, they were swinging helplessly below their parachutes as German tracer fire raced up at them.

The landscape below was in maelstrom. Pillars of smoke rose into the sky. The heath was on fire. At least 24 paratroopers were killed or wounded during the drop.

The Germans withdrew from the Ginkel Heath before the drop ended. (Middlebrook, pg. 237) British Gliders were also landing at LZ X. After A and C Companies of 2nd Battalion (South Staffords) left their gliders, they were rushed towards Arnhem, to try to link up with Frost. At 1515 hrs, the 11th Para Battalion was also sent after the Staffords towards Arnhem.

Both the Staffords and 11th Para realized what their compatriots had discovered the day before – that it was no ordinary thing to cover the six to eight miles to Arnhem on foot and under fire.

Closer to Arnhem, 1st and 3rd Para, already suffering from heavy casualties (about 200 men had been killed in action (KIA), or were wounded in action (WIA) or had become prisoners of war (POWs)). Nevertheless, the battalions were again trying to reach Frost at the Arnhem bridge in the face of fierce resistance from Kampfgruppe Spindler.

As 3rd Para closed to within 2,000 metres of the bridge, confused street fighting erupted – and that put an end to 3rd Para’s efforts to reach Frost on that day.

As night began to fall, the rest of the Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade left Ginkel Heath and moved along the railway towards the high ground north of Arnhem which was their objective. They reached the southeast corner of LZ S before darkness fell.

The rest of the British 1st Airborne, which had been holding the landing grounds at Ginkel, Renkum, and Wolfheze abandoned these places and took up position to the east, around the Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek and extending down towards the Lower Rhine at Heveadorp.

The Hartenstein Hotel became the headquarters of the British 1st Airborne.

Tanks come for the British

By Tuesday morning, the 1st Airborne was in three main parts. Frost and his men were still firmly sealed in at the bridge, and desperately short of ammunition. “Approximately four [British] battalions were trying to batter their way in towards us, with the enemy besetting them from all sides,” Frost wrote later. (Frost, loc. 3563, 76%)

By now, Dutch excitement at the prospect of liberation had waned as rumors spread that the British were in trouble. (Ryan, pg. 343) At Velp, over three miles to the east, Audrey Hepburn and her family had taken to the cellar of the Villa Beukenhof. The sounds of the battle at the bridge intruded into the basement. Even though the van Heemstras could not see the fighting, they knew that things were going badly.

Meanwhile, a stream of German reinforcements drove towards Velp and Arnhem. By the evening of 18th, members of the Dutch resistance were ashen to see German tanks and fresh troops moving through Velp, towards Arnhem. True horror was coming for the British at the bridge. Henri Knap, the head of the Arnhem underground’s intelligence, telephoned the Hartenstein Hotel to warn the British.

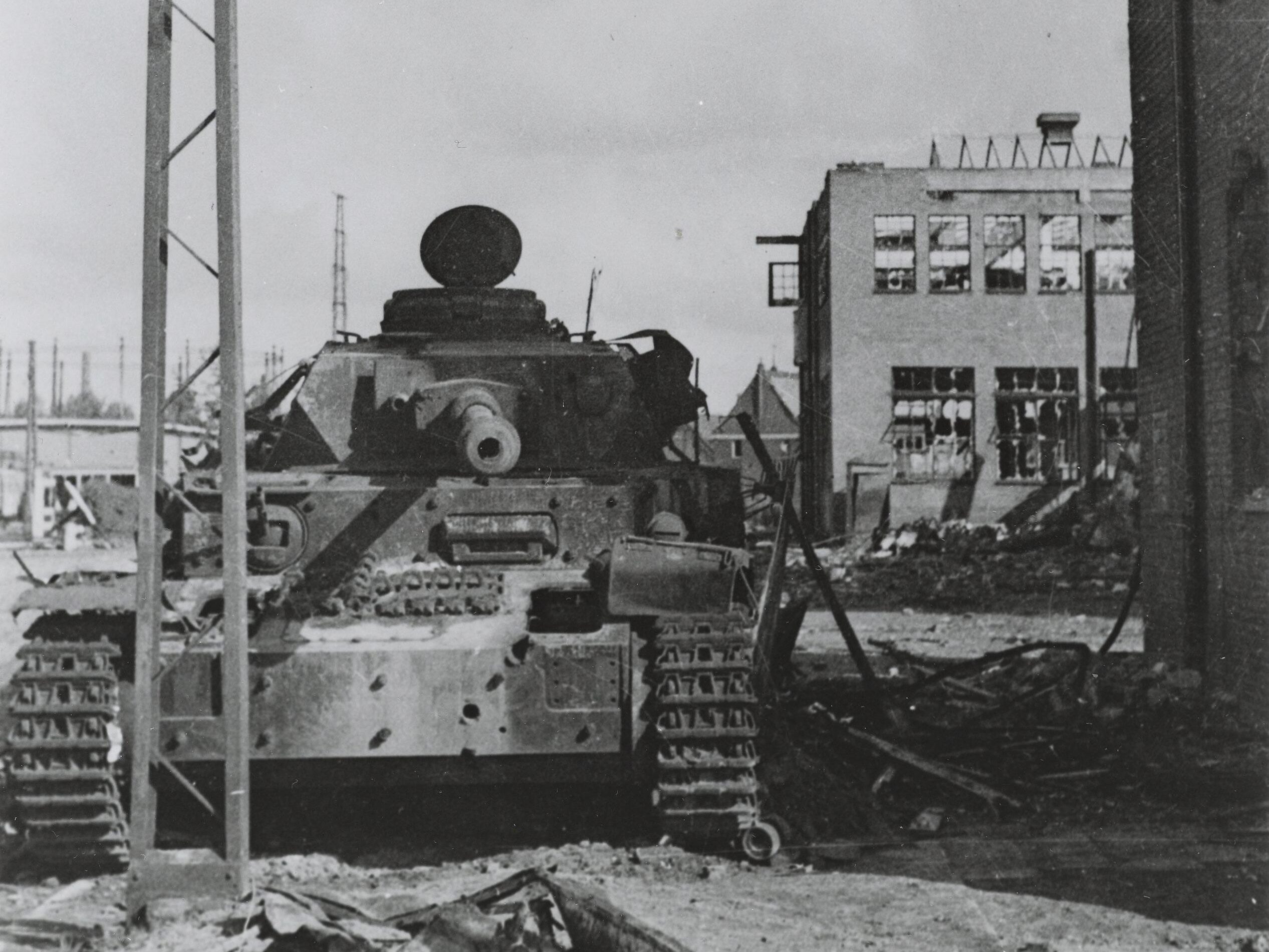

We know now that the German armor included seven Sturmgeschütz (StuG) IIIs and three Sturmhaubitze (StuH) 42 assault tanks of the 280th Sturmgeshutz Brigade.

These were followed a day later (on the 19th) by 14 Tiger I tanks of schwere Panzer Kompanie (heavy tank company) Hummel. Some 28 Tiger IIs from two companies of the 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung (heavy tank battalion) arrived in the Arnhem sector on 23/24 September. (Zwarts, pgs. 5-6; 26, 56, & Wolfgang Schneider, Tigers in Combat I (Stackpole, 2004), pg. 272)

The British officer who took Knap’s call asked the resistance man to hold on. When he came back on the line in a few minutes, he thanked Knap but his tone was skeptical. “The captain is doubtful about the report,” the officer said. “After all, he’s heard a lot of fairy tales.” (Ryan, pg. 343)

Once again, British distrust of the Dutch resistance would undermine their command of the situation.

The tanks hit Frost’s perimeter first, from the morning of the 19th. The fighting was bitter. SS Squad leader Ringsdorf again summed it up:

This was a harder battle than any I had fought in Russia. It was constant, close range, hand-to-hand fighting. The English were everywhere. The streets for the most part were narrow, sometimes not more than 15 feet wide, and we fired at each other from only yards away. We fought to gain inches, cleaning out one room after the other. It was absolute hell! (Kershaw, pg. 126)

Despite the brutality of the fighting, there were unexpected moments of decency. The SS often allowed wounded British to be evacuated from buildings, and they also respected the Red Cross flag, allowing British wounded through the battlelines to St. Elisabeth’s hospital which had become the primary aid center in the Arnhem area.

When the Germans occupied the hospital on 18 September, they allowed British surgical teams and even the Dutch civilian staff to carry on working, treating wounded from both sides. (Margry, Part IV, Ch 3, Loc. 8419, 59%, image caption)

That is not to say that SS could not be brutal. In one incident, the SS stopped a jeep with wounded under a Red Cross flag. When one of the medics tried to explain that the wounded were being transported to a casualty station, the SS lit him up with a flamethrower and walked away. (Ryan, pg. 493)

At Oosterbeek, the ter Horst family had graciously turned their large family home into a regimental aid center. The family matriarch and housewife, Kate, was the mother of five children. She helped doctors to care for the British wounded and comforted the dead and dying with readings of psalms from an English-language bible.

A German tank began to shell the house. Enraged, a 1st Airborne medical orderly, Bombardier E C Bolden, grabbed a red cross flag and rushed out.

“What the hell are you doing?” Bolden screamed at the German tank commander. “ This house is clearly marked with a Red Cross flag. Get the hell away from here!”

Astonishingly, the German tank commander apologized and backed off. (Ryan, pg. 493) While these incidents are anecdotal, it is almost impossible to reconcile such acts of decency by the Germans (especially the SS) with their barbarous actions in Soviet Russia.

Defiant to the End

That Frost and his command were able to hold the bridge for so long was partly due to their unconventional, almost egalitarian command structure built on mutual respect between all ranks.

Captured Germans were astonished to see rank-and-file British paratroopers being “close and informal with their officers”25 – Something unseen in the German army, much less the traditionalist British army, with its classist divide.

Frost’s fighting spirit and that of his men never appeared to waver, even as they were pummeled in their perimeter. Even late into their ordeal, on the 19th, when the Germans sent a captive British airborne engineer to convince Frost to surrender, his fierce determination to win was manifest when the engineer revealed that the Germans were actually “disheartened” at their own heavy losses.

In a flash, Frost realized that if “only more ammunition” arrived they would “soon have” their “SS opponent in the bag.” (Frost, loc. 3587, 76%)

But no ammunition reached the airborne. By the afternoon 19th, Urqhuart had realized that he had no way to help Frost. (Hilary St. George Saunders, The Red Beret (Battery Press, 1985), pg. 248)

Major General Sosabowski’s Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade had been due to drop on the south bank of the bridge on the 19th, but bad weather in England had postponed the drop. Had the Poles dropped on time, they may have well saved the situation.

As night fell, the entire town of Arnhem appeared to be on fire, including the two large churches.

By the 20th, German tanks were 30 yards from British positions at the bridge and were systematically shelling each building. At about 8 am, Frost’s radiomen were finally able to raise a British unit outside their perimeter – the 1st Airlanding Light Artillery Regiment via its Type 19 radio.

Major Freddie Gough was able to talk to Urquhart who relayed that the rest of the 1st Airborne, was under heavy attack, and was in “poor shape.” They had no way to reach the bridge, Urquhart told Gough.

Frost had under 100 troops in fighting form, carrying on with what little ammunition was available, killing Germans in droves. Among his fighting men was a single American, Lieutenant Harvey Allan Todd, a former high school teacher and football coach from Illinois.

Todd was part of a Jedburgh Team, one of 99 such Allied special operations teams created during the war to help organize and arm the resistance movements in Europe, arrange supply drops, procure intelligence, and provide a liaison between the Allies and the Resistance. (Office of Strategic Services: Jedburghs, US Army, https://www.soc.mil/OSS/jedburghs.html)

Part of a joint US-British-French program26, most Jedburgh teams comprised three personnel and Todd’s team (codenamed “Claude”) was no different.

The team landed with Lathbury’s 1st Parachute Brigade at Renkum Heath on 17 September.

Soon after, its wireless operator, US Technical Sergeant Carl Scott, became separated from the rest of the team and never saw them again. This left Todd with only his team leader, a Dutch Captain named Jacobus “Jaap” Groenewoud, for company. But a German sniper killed Groenewoud at Arnhem on the 19th.

As the remaining member of his unit, Todd became a one-man killing machine within Frost’s command.

In his post-war debrief, backed up by British reports, Todd spoke of using a Bren light machine gun to take out a German 20 mm flak position 130 yards away on the 18th, of killing half a dozen Germans using a sniper rifle over the next 48 hours, of silencing a German rooftop machinegun post on the 20th, of having been blown out of his position by tank fire later that day, of fighting fires and rescuing wounded Airborne at the brigade HQ that night, and of having destroyed a second German machine gun post on the 21st with a grenade. In all, Todd claimed to have single-handedly killed 16 German soldiers. He was awarded the US Distinguished Service Cross.27 (See Will Irwin, Abundance of Valor (Ballantine Books, 2010))

And what happened to this Rambo-like individual after the war? Todd became an insurance agent in his native Illinois.

Later that same day, Frost was badly wounded in the legs by a mortar bomb, and Major Freddie Gough of the 1st Airlanding Reconnaissance Squadron took command of the perimeter. Unbeknownst to both of them, salvation could be had from England, if Browning wished.

Major General Edmund Hakewill-Smith, commander of the British 52nd Airlanding Division had offered to land one of his brigades by glider on the southside of Arnhem bridge. Landing a large number of gliders on the southside polder would have resulted in casualties among the troops within. Nevertheless, the arrival of an airlanding brigade on the southern side of Arnhem bridge would have saved Frost’s command and won the operation for the Allies.

Browning responded: “Thanks for your message, but offer not – repeat not – required as situation better than you think. We want lifts as already planned including Poles.” (Middlebrook, pg. 413)

By the start of the 21st, the bridge defenders were almost out of ammunition. Finally, the Germans intercepted a radio message sent out on the air from someone within the bridge perimeter: “Out of ammunition. God Save the King.” (Ryan, pg. 430)

All able-bodied survivors at the bridge perimeter were ordered to split up and try to escape the German cordon. But German SS troops moved swiftly into the broken perimeter and began to round up the paratroopers. Frost was among the captives.

The paratroopers all knew of the SS penchant for cruelty and braced for the worst. To his surprise, Frost was taken aback by how “polite” the SS were and how “complimentary [they were] about the battle we had fought.” It was clear that Germans were relieved that the battle for the bridge was over.

“But the bitterness I felt was unassuaged,” Frost wrote later. “No living enemy had beaten us. The battalion was unbeaten yet, but we could not have much chance with no ammunition, no rest and with no positions from which to fight.” (Frost, loc. 3662, 78%)

Gough was also a prisoner. A German major sent for him, gave him the Hitler salute, and said: “I fought at Stalingrad and it is obvious that you British have a great deal of experience in street fighting.”

“No,” Gough told the German. “This was our first effort. We’ll be much better next time.” (Ryan, pg. 430)

Sosabowski’s Choice

Sosabowski and two-thirds of the Polish Para brigade (1,002 men) finally landed on 21 September, on a new drop zone further west of the bridge and south of the Lower Rhine, near the village of Driel.

Their orders included using a small ferry at Heveadorp to cross over to Oosterbeek. But the ferry was at the bottom of the Rhine; destroyed by its boatman who feared its use by the Germans. Sosabowski was furious. (Middlebrook, pg. 406)

Soon, Sosabowski’s force was under siege from German tanks and infantry which had crossed south from the Pannerden Ferry and the now-open Arnhem bridge. Fortunately, units of the British 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division linked up with the Poles at Driel on 22 September.28

The Wessex’s relief force included DUKW amphibious trucks carrying ammunition, supplies and stores. (21st Army Group, pg. 62) The Poles received a few small boats and at least one dinghy with which to traverse the Lower Rhine.

But efforts to cross the river on the 22nd and early in the morning of the 24th were met with German illumination flares and heavy fire from the northern bank.29 (ibid., pgs. 63-64) Nevertheless, some 205 Poles managed to reach the 1st Airborne, where they took up position with Shan Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade. (Sosabowski, pg. 251; 21st Army Group, pg. 67)

Crossing the Lower Rhine to the 1st Airborne Division

| Date | Men crossed | From Unit | Time of crossing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22/23 September | 52 | Polish 3rd Battalion | 10 pm to 4 am |

| 24 September | 153 | Polish 3rd Bn, Anti-Tank Battery, Brigade HQ | 3-5 am |

| 25 September | 350 | 4th Dorsets, personnel from 112th Field Regiment, 22 personnel from 181 Airlanding Field Ambulance; Lt. Col. Tommy Haddon (Co, 1st Border), Haddon’s intel officer, plus two other men; Major Pat Anson (10th Para); | 1.30-2.15 am |

The British wanted more of the Poles over. On the 24th, the commander of the 43rd Wessex, Major General Ivor Thomas (a dour, unpopular commander nicknamed “Butcher” by his own men) started out giving orders to Sosabowski, telling him that the Poles’ 1st Battalion would cross the river that night with the 4th Battalion (Dorsets).

Sosabowski was annoyed that nobody had consulted him about this before. Thomas’ language also defied basic military courtesy. “Excuse me, General,” Sosabowski told Thomas. “But one of my battalions selected by me will go there.” (Sosabowski, pg. 254)

This annoyed Thomas. Sosabowski then compounded the matter by urging Thomas to land the entirety of the 43rd Division and all of the Polish Brigade further west from German defensive concentration to establish a strong riverhead. Thomas took the advice badly. Horrocks had to defuse the situation lest it erupt into a full blown argument.

Sosabowski then ameliorated his relationship with Browning that same day with further acts of forthrightness. During an informal meeting, Browning suggested to Sosabowski that the “river crossing may not succeed as there is no adequate equipment.”

Sosabowski was “thunderstruck.” In a moment of anger, he criticized the British generalship for initiating operations across river country without the foresight that boats may be needed. When Sosaboswki suggested that every minute of delay meant more deaths within the 1st Airborne, Browning looked wounded and ended the meeting. (Sosabowski, pgs. 255-256; Middlebrook, pg. 416)

This would have ramifications later. The British should have taken Sosabowski’s words as one of genuine concern over perceived flaws in operational plans that could be addressed and resolved. Instead, they appeared to take it as personnel criticism.

The lack of boats for the Poles meant that only the 4th Dorsets could cross the river that night, along with some artillery and medical personnel, plus some 1st Airborne parachute and glider officers whose aircraft had failed to reach the Arnhem area. They landed among the Germans and a battle erupted – as Sosabowski had previously warned it might.

The Dorset battalion fragmented into small groups and most them could not even locate the 1st Airborne lines. (21st Army Group, pg. 70) The Germans captured about 200 of the 315 Dorsets who had made the crossing and at least 13 died at some point. (Middlebrook, pg. 422)

The 1st Airborne was now fighting for its life. Frost and his bridge defenders had been bulwarks, keeping major SS and Heer (Army) combat units at bay from the rest of the division. After they were destroyed, German armor, artillery and infantry were free to converge upon Urquhart at Oosterbeek.

XXX Corps’ British 64th Medium Artillery Regiment at Nijmegen, guided by observers within the “Red Devil’s” perimeter, repeatedly broke up German tank attacks. (Ryan, pg. 439) However, the dysfunction of the RAF tactical forces was manifest at this late hour when even their air power was unable to adequately help Urquhart.

The 1st Airborne had received virtually no tactical air support at all. (Allied Airborne Operations in Holland, pg. 23)

“The lack of close air support was a surprise to us,” Urquhart said. “In the first two or three days before the flak started to build up, low-flying rocket aircraft would have been invaluable…. rooftop attacks by Allied fighters on tanks in the streets would have made a lot of difference.” (Urquhart, pgs. 216, 260, 283-284) It is incredible that Urquhart was not informed about the dubious air support arrangements made before the operation began.

Only from 22 September (D+5) did the 2nd TAF finally make some effort to support the “Red Devils” with its Hawker Typhoon fighter-bombers.

A big, brutish-looking aircraft armed with four 20 mm cannons and capable of carrying and launching eight 3-inch rockets, the Typhoon was a formidable aerial threat to the Germans. The Typhoons began pummeling the area outside the 1st Airborne perimeter, and on 22 September, even levelled a factory that the Germans were using for sniping and observing the “Red Devil’s” perimeter. (Allied Airborne Operations in Holland, pg. 14)

Members of the 1st Airlanding Recce Squadron saw Typhoons for the first time during Market on the afternoon of 24 September. The aircraft roved low over the landscape, menacing seemingly omniscient entities, hunting for targets. Rockets sparked to life from their underwing hardpoints and roared towards a target. A massive cloud of smoke heralded destruction.30

Sometimes, the 2nd TAF sorties were ineffective as the Germans learned to hide and hold their fire when the Typhoons were overhead, according to the war diary of the 1st Airlanding Recce Squadron.

“Germans pretend that they are not there at all, and that they love us,” the diarist noted dryly.

Out with a Whimper

By the 25th Montgomery had decided to end the operation. Commanders, like Sosabowski and others, were in favor of keeping the offensive going, because the Arnhem bridge was still intact.

However, 21st Army Group HQ had decided that the Oosterbeek area was “not suitable for development as a Corps bridgehead owing to difficulties of expansion and the impossibility of building and maintaining a bridge in this area.” (21st Army Group Report, pg. 106)

Nevertheless, another bridgehead could have been established further west over the Lower Rhine. But it was not to be. Montgomery had run out of time. He had no way to send the 1st Airborne sufficient supplies and ammunition to stay in the fight, and he could not yet launch a concerted amphibious assault across the river to relieve them. The only option was to evacuate the 1st Airborne as quickly as possible. (Montgomery, pg. 146)

He ordered the retreat. The remnants of the 1st Airborne from Oosterbeek and the survivors were to start crossing south, over the lower Rhine that night. The evacuation was supported by two British engineering

units, the 553rd and 260th Field Companies (Royal Engineers), and two Canadian units, (the

20th and 23rd Field Companies, Royal Canadian Engineers).31

Operation Market-Garden was over, and all the Allies had to show for it was a mass of casualties and a bridgehead at Nijmegen leading nowhere. In October, the Allies bombed and destroyed the Arnhem bridge to prevent the Germans from using it to deploy more armor onto the south bank.

Out of the 8,969 1st Airborne Division troops who landed eight days before, less than 1,600 returned, including Urquhart and the airlanding brigade commander, Pip Hicks. About 200-300 of those left behind would later escape, including both parachute brigade commanders, Lathbury and “Shan” Hackett, but the rest were dead or in German hands.

On the 26th, the British wounded at the St. Elisabeth Hospital in Arnhem heard marching troops approaching, their voices full of English song. For a moment, they thought that XXX Corps had finally reached them.

When they hastened to the windows, they found it was some 500 British airborne from the Oosterbeek perimeter, weaponless, some lurching forward with the support of sticks, their uniforms caked a “filthy brown color,” their eyes red and bloodshot, with armed Germans walking alongside, leading them to captivity. (Urquhart, pgs. 265-266)

As the captive airborne went by in song, Urquhart wrote that Dutch civilians watched on with admiration, and that even the Germans were in awe. “There were many who witnessed this strange sight who say that the men looked unbeatable and that it was more like a victory march,” Urquhart said. (Ibid.)

Perhaps that was wishful thinking on this part.

Articles in the British press began to appear on the operation, portraying the failed operation as a victory, and with no mention of the Americans at all (except for a brief mention in the Daily Telegram on 22 December). American paras soon realized that it was Montgomery’s interest to portray the loss as a victory. (Gavin, pg. 186-187) Adding to their annoyance was that the US press also failed to mention the contributions of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

Browning was one of those who was trying to rewrite reality. In a letter to his wife, the novelist Daphne du Maurier, he wrote: “Roy Urquhart’s party has done magnificently but have been very badly knocked about. They have covered themselves in glory and without them we couldn’t have done what we have done.” (Richard Mead, General ‘Boy’ (Pen & Sword, 2010), Ch 20, Ref. 26.22, 51%)

What had “we” done anyway?

*The Imperial War Museum (IWM) previously identified this officer as South African Major N Coxon of 1st Para. However, information suggests Coxon was no longer with 1st Para by September 1944. Some historians have since identified the man as McCombe. Was he McCombe? The dark splotches and bandages on his face make facial identification difficult. At the same time, the officer in the picture has the rank of major on his epaulets; McCombe had the lower rank of Captain at the time.

In reality, the goose-stepping, right-arm raising, servile cogs of the Third Reich, in their fast-moving ad hoc formations were the true victors of the campaign.

As the 9th SS commander, Harzer said after the war, Nazi Germany had prevailed using troops that were mostly unsuited to combat, either by virtue of being untrained or being ill-equipped. (David Bennett, A Magnificent Disaster (Casemate, 2008), Ch 14, 76%)

Even Montgomery conceded that battle was lost because the Germans “managed to effect a surprisingly rapid concentration of forces.” (Montgomery, pg. 149)

The German victory meant that Montgomery could not even silence the V-weapon sites which were shelling London and Antwerp, and it put paid to the optimism that the war could be ended by Christmas 1944.

Allied Casualties, 17 to 25 September 1944

| Unit | Total Strength | Fatal Casualties | POWs & Evaders* | Wounded | Missing | Total Losses | Evacuated safe from Arnhem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British 1st Airborne Div | 8,969 | 1,174 | 5,903 | A | 7,077 | 1,892 | |

| British Glider Pilots | 1,262 | 219 | 511 | A | 730 | 532 | |

| Polish 1st Para Brigade | 1,689 | 92 | 111 | A | 203 | 1,486 | |

| US 82nd Airborne Div | B: 11,994 | 215 | Unknown | 790 | 427 | 1,432 | N/A |

| US 101st Airborne Div | 11,237 | 315 | Unknown | 1,248 | 547 | 2,110 | N/A |

| HQ Br I Airborne Corps & Signals | 195 | 4 | Unknown | 0 | 8 | 12 | N/A |

| US Glider Pilots | Unknown | 28 | 26 | 58 | 112 | N/A | |

| British No 38 Group | Unknown | 6 | 23 | 184 | 213 | Unknown | |

| British No 46 Group | Unknown | 8 | 11 | 62 | 81 | Unknown | |

| US IX TCC | Unknown | 16 | 204 | 82 | 302 | Unknown | |

| Known Totals | 35,346 | 2,077 | 6,525 | 2,302 | 1,368 | 12,272 | 3,910 |

A: 2,000 to 2,500 in total for men from the British 1st Airborne, British Glider Pilots Regiment and the Polish 1st Para Brigade. These stats are not counted in the total losses as they are already counted in the “POWs & Evaders” column.

B: This is my estimate of the minimum number of troops the division had, due to insufficient information on how many 82nd AB troops landed on 23 September.

N/A: Not Applicable

Sources:

Allied airborne operations in Holland, pg. 5; Report of airborne Phase (17-27 Sept., 44) Operation “Market”, XVIII Corps, pg. 84; By Air To Battle, pg. 98.; MacDonald, Siegfried Line Campaign, pg. 199; Margry, 24%; Middlebrook, Ch 21.

German Pyrrhic Victory

The German victory while decisive, was pyrrhic.

The Allies suffered at least 12,272 casualties during the operation, including 2,077 killed. German losses are less certain. Allied after-action reports, however, provide strong estimates.

In the Arnhem sector, Urquhart estimated that his division caused 7,000 German casualties. (Urquhart, pg. 261-262). According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Bittrich’s SS II Panzer Korps alone suffered between 1,300 to 1,725 killed-/missing-in-action and 2,000 wounded-in-action casualties, as of 27 September.32

Some of the German missing-in-action (MIA) cases would have been taken prisoner by the British. In all, the British 1st Airborne held about 2,220 German POWs. However, following the collapse of the 1st Airborne perimeter, the Germans reclaimed most of its captive men (and at least one servicewoman) from British custody.

In the 82nd Airborne sector, the “All Americans” eliminated at least 2,763 Germans from the battlefield (including killed, captured and wounded) between 17 and 20 September (during the airborne phase of the operation). The 101st Airborne inflicted about 2,000 casualties on the Germans (in addition to having taken 3,511 POWs) from 17-26 September. Between 17 and 26 September, XXX Corps also captured 1,066 Germans.33

This produces a minimum casualty figure of 11,574 for Nazi Germany.

Hi thereYou write so brilliantly. Such clarity, such mastery of the language.Thanks for sharing.I had a friend, a Dutch – Indonesian woman, whose father took the family to Holland

Hi. I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you – for sharing about your friend!

Actually, my original message got truncated. So here is the remainder

My friend was about 10 when the War began and she spent the duration in Arnhem. She witnessed many horrible things, including people being shot in the street. And some of the fighting. The family suffered greatly from food shortages too.

The War left a lasting impression as you can well imagine, I am sure.

Best wishes

Steve (I’m the guy who sent you the books on WW2 in Burma)

Hi Steve, good to hear from you! I still have the books on my shelf.

I can only imagine the trauma she must have experienced. Did she record any of her experiences?

No, and she passef away years back. Her father was an engineer on the Dutch East Indies Railway in Java. Went to Europe with the family around the time of Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace in our time”

Bad mistake. At war’s close they returned to Java, but like a lot of Dutch and Indo-Dutch, fled to Irian when Indonesia won the war of Independence in 1949.

Lived in Irian until the “Act of Free Choice” in 1963, from memory. What a joke that was.

Then migrated to Australia to build a new life. Lovely woman who married a lovely Australian guy.

Cheers

Steve

That is so interesting. Thanks for sharing this information, Steve. Mighty grateful.

The civilian experience at Arnhem is understudied in English-language history. Documents indicate that 453 civilians died during the Arnhem battle. I can only imagine the plight of the civilian populace caught up in the battle.

She spent the War living in Arnhem. She was a young woman. She witnessed many horrors. It was an experience that coloured the rest of her life.

Wow Akhil!!! Need some time to digest this :). Great stuff I’m sure!!Marco Cillessen

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts, Marco.

For anyone interested, there is an episode from Thames Television Tv series U.K called “This is your life” filmed in the seventies (i think).One episode featured Major General John Frost CB DSO &Bar MC DL.Towards the end of the show a group of men who were with him came on as a suprise.This episode on YouTube.Also on there, is a tour of the bridge and a first hand account of the fighting in around it by Steve Morgan of 2 Para at the time, a lovely man.

Dear Akhil ,

First my compliments on a verry good website.

But the foto`s of the railway bridge in Oosterbeek are both not from the battle.

The first one is from after the war and the second on is from may 1940 and shows the damage done by the Dutch Army on the 10th of may when all the bridges in the surrounding of Arnhem and Nijmegen where Blown.

The book: The lost Company, by Marcel Anker (2017) will show howe the bridge looked before and after the battle

Kind Regards

Hans Wabeke

Thanks for this valuable information. I will delete the images.

The Horsa Glider could take the 6 pounder AT gun but NOT the 17 pounder AT these where flown in by the Hamilcar gliders.

You are absolutely right. Thanks for pointing this out.

The pictures of the railway bridge are NOT from the batlle in 1944, the first on is from after the war and the second shows the bridge in may 1940. Alle the bridges around Arnhem and Nijmegen where destroyed by the Dutch Army in the early morning of the 10th of may 1940.

Yes, this has been pointed out to me. There was brief imagery of the broken bridge from “Theirs is the Glory”. I need to see if I can find that footage.

The book “the lost company” by Marcel Anker (2017) contains pictures from the bridge before and after the battle

The book seems to be out of print, sadly. Let me check if I can source it somehow.

Try ‘Meijer&Siegers”Bookstore in Oosterbeek

Thanks.

“bolt-action .303-inch (7.7 mm) Lee-Enfield rifles (sheesh!)” Why “sheesh”? The standard firearm of the German army was also a bolt-action rifle; both rifles in the hands of a trained soldier are deadly. This piece comes across as very condescending towards the British, from the Generals right down to the firearms.

Hi,

Thank you for your comment. It is appreciated. What is your name, by the way?

In my view, the issuance of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield No. 4 to the airborne forces gave the paras/glider troops a weapon that was not only heavy but also cumbersome in close-quartered fighting, not to mention that it could not give airborne forces an adequate volume of fire to match that of the Germans. Sure, the Germans also had the Kar98K, but their airborne forces also had the automatic FJ42, the semi-automatic Gewehr G43, the StG44, not to mention the venerable MP40 and the MG42 which could produce a heavy volume of fire. By the way, I make mention later on in the monograph that some Paras at Arnhem demonstrated their adroitness with the Lee-Enfield through sheer shooting accuracy.

Also, in Urquhart’s book, a few negative things are said about the Sten Mk V and how it was a “temperamental weapon at best” – a comment I found dismaying. I also have some data in my files somewhere about how the US M1 Carbine found some favored use in the 1st Airborne Div.

Anyway, I reject the charge of condescension. Have you read my other pieces on this website? They are replete with tellings of British heroics and achievements, whether they be on Malta, in Burma with the Chindits, in Normandy (even during the stalled Epsom offensive) or in North Africa.

My name is Martin, I’m not sure where the “furry” so and so came from, the Chindits is an excellent piece indeed, as is most of your stuff, especially the liberation of Paris, sorry I shouldn’t moan, you do an excellent job, and I see where you are coming from, it took the British army far too long to get a semi automatic rifle into service, saving ammo on the generals minds no doubt, now I’m doing it lol.

Thank you, Martin. I am grateful for your candor! At the end of the day, I am happy to discuss/debate any queries about my research – and WWII in general- time permitting.

Thank you Akhil

“armed with the new Sten Mk V variant (a version that incorporated a wooden stock and foregrip, representing a major enhancement of an ugly wartime weapon made out of stamped sheet metal).”

The Sten Ugly? Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Now, I give you that the MKV might be improved, but it was a hell of an ugly improvement, to my eye anyway. 😀 Still, for me, the MKII Sten is the most beautiful submachine gun of WW2. Still, I am partial to brutalism, and the Sten cost tuppence ha’penny at a time when Britain needed a sub machine gun quickly and the Lanchester, while a lovely weapon, was too time-consuming and expensive.

Just a few thoughts, currently reading your Stalingrad, it is excellent, if I could just add here that I think one of the reasons the Germans liked the PPSH so much was it’s 50 round drum magazine.

The Sten Mk II is the iconic variant of the weapon and gave Britain a high-value frontline weapon at a fraction of the cost, I agree. But the Mk II is also hard on the eyes! The Sten Mk V is a more elegant-looking weapon (IMHO), and with its wooden stock, pistol grip, and foregrip, had improved handling.

The Stalingrad piece is old now; written years ago. Sadly, I lack the time to do a refresh.

I feel that the PPSh-41 was a formidable weapon. However, as you may know, most of these SMGs were hobbled by limited range (as per Ian Hogg, the effective range of the Thompson SMG was 50 m, that of the Sten Mk II was 40 m; the PPSh-41 and the German MP40 had better effectives ranges of 100 m). Stopping power is a separate matter. In any case, these SMGs were effective only as close-quartered weapons. Going back to Arnhem, it is arguable whether the 1st Airborne would have befitted from having more automatic weapons such as the Sten Mk V, Thompson or M1 Carbine (effective range: 180 m), when considering factors such as volume of fire versus ammunition availability.

Also, if I may add to my previous comment about the Lee-Enfield No 4 rifle: According to Lt. Col. H F Joslen’s, Orders of Battle, Second World War, 1939 -1945, the standard basic allowance for a British Airborne Division in 1944 included: 7,171 Lee-Enfield No 4s, 6,504 Sten Mk Vs, and 966 Bren LMGs (to mention a few weapon types). The actual number of weapons issued to the 1st Airborne would have varied slightly, but it is likely that the Lee-Enfield was the predominant small arm in the division in September 1944. The employment of the M1 Carbine during the Arnhem battle appears to have been limited to troops within the 1st AB HQ and the Glider Regiment. During my research, I didn’t pay much attention to the number of M1 carbines or other small arms issued, so I don’t have a number on how many M1s were used in the Arnhem sector. Perhaps a visitor to this site has the answer.

Pingback: Colors of the Caribbean