This page provides a brief history of the Normandy campaign through 19 maps. A viewing of the old film The Longest Day at the age of 12 or 13 first stoked my interest in the campaign. The battle for Normandy, in my febrile mind, represented a classic struggle of good versus evil, broadly speaking anyway. But if I grew up suitably enlivened to contribute something to the collective body of work on the campaign, it was tempered by the realization that most of what can be said has already been written or depicted.

Where the historical treatment of Normandy has lagged, however, is in maps. It is difficult to build a sense of location and understand the physical implications of strategic maneuvers without compelling maps. The history of Normandy is replete with insufficient maps. I wanted to try to address that.

The maps below were created in 2018, over the course of six or seven months. They represent my first serious effort at complex mapmaking. The project was also, to a degree, about self-education.

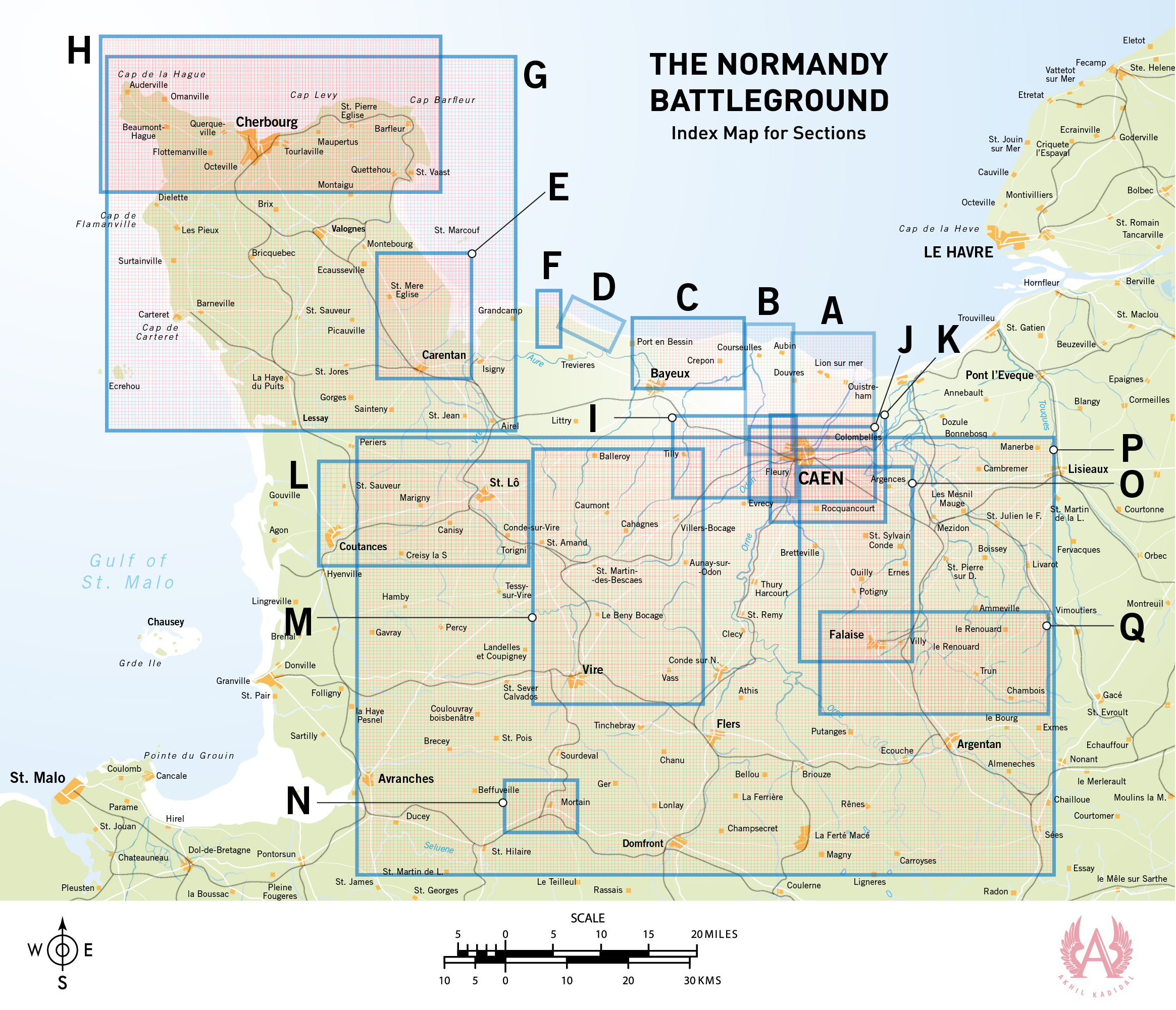

An Overall look at Operation Neptune

The prospect of returning militarily to France aroused feelings of anxiety within British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, haunted as he was by the specter of another Allied defeat in France followed by a Dunkirk-like evacuation of the survivors. For years, he had postponed a cross-channel invasion of western France by cajoling and manipulating his American allies into military expeditions in the Mediterranean. He had assured Washington DC that a strike through the soft underbelly of Italy could pierce Nazi Germany. By 1943, however, the United States was convinced that the Third Reich could only be defeated through a direct assault on Hitler’s “Atlantic Wall”, an incomplete line of coastal fortifications which threaded from southwestern France to Norway.

Allied planners, however, knew that coastal defenses, no matter how dense, offered little impediment to an amphibious assault. An Allied plan began to coalesce. Twelve Allied divisions (roughly 156,000 men) were nominated to pummel their way into German-occupied Normandy and hew an iron beachhead from which Allied troops could range deeper into Nazi-occupied Europe.

The invasion, D-Day, was launched on 6 June 1944.

Churchill spent much of 5/6 June in a state of angst, fearing that the invasion, codenamed Operation Neptune would fail, dealing the western alliance a critical setback that force them to marshal manpower for another invasion in late 1945 or 1946 — by which time Hitler could have used his western reserves to smash the Soviets on the eastern front.

Yet, the bulk of Germany’s forces along the Norman coast were tired, rear-echelon units with substandard equipment. The most combat-effective division in the area was the 12,734-strong German 352nd Infantry Division, which had almost no combat experience (50% of its officers were green while the rank and file was largely made up of teenagers from the Hannover area). Only the presence of a hardened cadre of veterans from the Eastern Front peaked the division’s fighting prowess to acceptable levels. Many of the infantry and static divisions in the area were inferior, with the exception of the 709th Infantry Division under the experienced Lt. General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, also a veteran of the Russian front.

Von Schlieben’s command, however, was less than stellar, being largely composed of men regarded as unsuitable for frontline service. The average age of a soldier in the 709th was 36 and their training had been minimal. Russian defectors padded out the infantry even though their combat effectiveness was questionable. The unit’s left flank, however, was bolstered by the German 91st Airlanding Division. Although green, the 91st Division was motivated and willing to fight.

The Allied armada, which left England on June 5, would take 17 hours to cross the English Channel while Allied paratroopers flew out after dusk to secure the flanks of the invasion zone, west of the Norman capital Caen and on the Cotentin peninsula, in order to stem the flow of German reinforcements into the beachhead assault zone.

At midnight, 13,348 Allied paratroopers began to descend onto Normandy, confusing German high command and infusing chaos among scattered German garrisons. Just after dawn, at 6 am, the Allied invasion fleet hove into sight off the Norman coast.

A. Sword Beach

B. Juno Beach

C. Gold Beach

D. Omaha Beach

E. Utah Beach

F. Pointe-du-Hoc

G. Advancing through the Cotentin Peninsula

H. Capturing Cherbourg

I. The British break the back of the German SS

J. The Allies capture half of Caen

K. A British Schwerpunkt Meets its Match

L. An American Cobra in Normandy

M. Operation Bluecoat

N. The Mortain Counterattack

O. The Big Push (Towards Falaise)

P. The Falaise Pocket

Q. Closing the Falaise Pocket

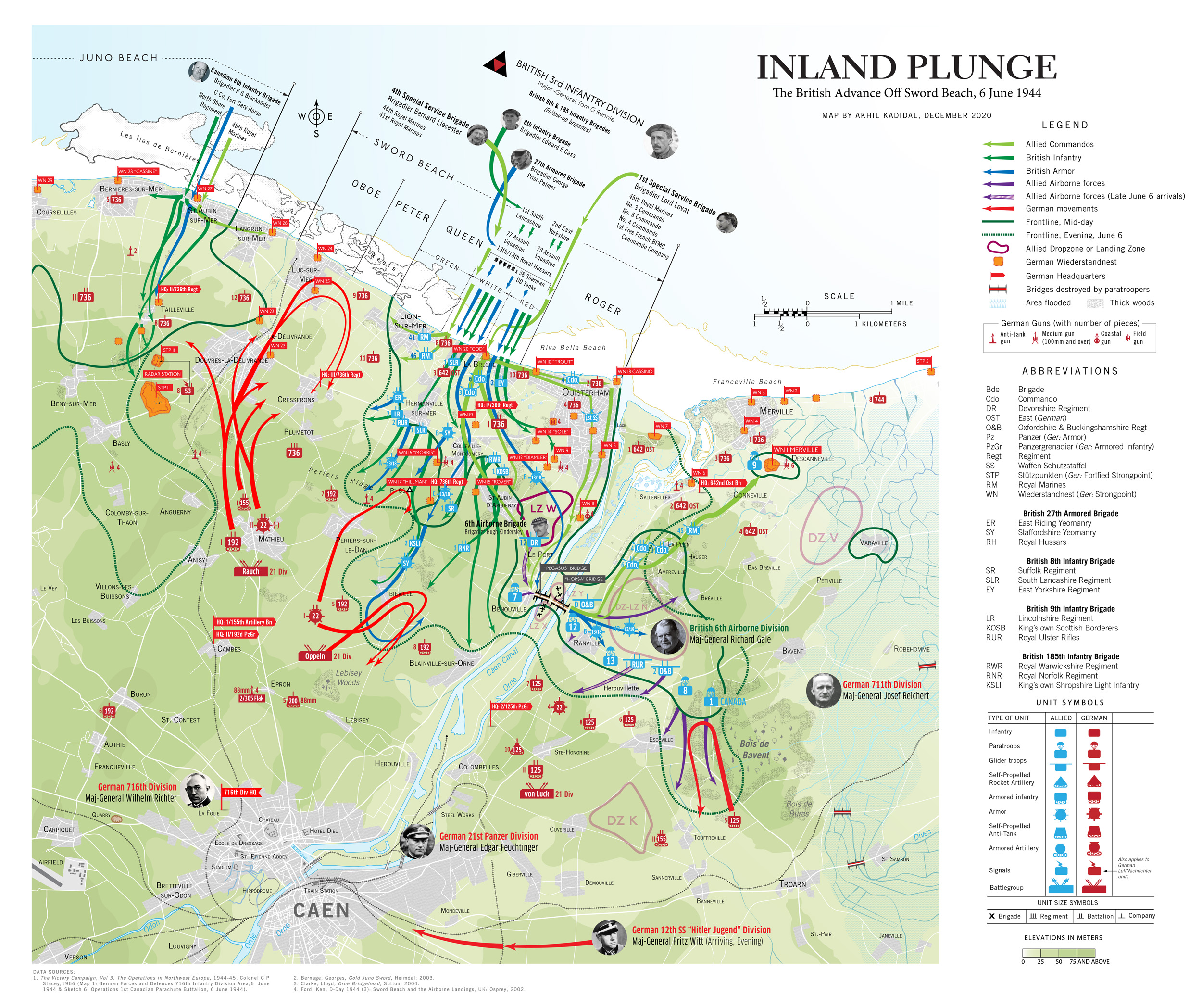

A | Sword Beach

I was an anglophile in my childhood and the actions of the British Army in the 20th century were an endless source of fascination. Great Britain and her military were exotic, replete with alluring organizational structures, practices, decorum, and traditions.

It was therefore predictable that my early interest in the Battle of Normandy hinged on the actions of the British Army, especially in the “Sword Beach” sector.

A crucially important sector, troops hitting “Sword Beach” were meant to roll up into the Norman capital, Caen (population 54,000 in 1944), whose great road hub would have facilitated an easy advance deep into Nazi-occupied France and to Paris, 149 miles away.

The unit handed the task was the British 3rd Infantry Division, the oldest command unit in the British Army with exploits ranging back to the Battle of Waterloo in the 19th Century. Bolstered by 4,000 commandos, plus an independent armored brigade with 212 tanks and the paratroopers of the 6th Airborne Division on their right flank, the 3rd Infantry Division pushed towards Caen on the morning of June 6, sweeping aside German resistance. Then, at midday, the sole German armored division in the area, the 21st Panzer, placed itself between the British and the city.

The 21st Panzer, once a fabled stalwart of the North African war two years ago was now a toothless tiger, replete with misfits and recruits — although 2,000 original members, having been hospitalized for wounds in North Africa, had returned to strengthen its ranks. Evidence of the 21st Panzer’s diminished standing was manifest by the fact that it had, until recently, been equipped with old, obsolete French tanks captured in 1940. By D-Day, it had been outfitted with the Panzer IV, a medium battle tank that was an even match for the Allied Sherman.

The German divisional commander, Major General Edgar Feuchtinger, behaved as though the running of his division was something of a chore, if not punishment. He spent more time lavishing attention on his mistress in Paris, than on working to get his division to full operational status.

In fact, Feuchtinger was once again philandering in Paris when the Allied invasion materialized, enraging his superior, Lt. General Hans Speidel, the Chief of Staff of Army Group B. As a chastened Feuchtinger raced back to Normandy on the afternoon of the 6th, the division activated itself and sent out patrols.

British tanks and Infantry streaming towards Caen began taking heavy fire as they reached the Periers Ridge, a stretch of high ground before the villages of Periers-sur-le-Dan and Bieville. Instead of smashing through, the infantry of the British 1st South Lancashire Regiment and the Shermans of the 13/18th Royal Hussars dug in. Aside from a smattering of German infantry and strung-out screens of antitank guns, there was virtually nothing between them and the city. They could have well been in Caen by mid-afternoon. But the commander of the British 8th Infantry Brigade, Brigadier Edward Cass, preferring to wait for reinforcements. It would prove a fateful decision.

Meantime, senior German officers were scrambling to deploy their armored reserves scattered around central and southern France.

At 9 am, nearly two hours after the beach landings, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the head of OberKommando West, attempted to rush the 12th SS (Hitler-Jugend) Panzer Division and the elite Panzer Lehr Division into the invasion zone. He was stalled by Field Marshal Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of Operations Staff in Berlin, who argued that only Hitler had the authority to move these units. But Hitler, a habitual late riser, was still asleep and would not awake before noon. When he did, he flew into a rage at the news of the Allied invasion. By when the armored units finally began to move, it was 4 pm.

By this time, British thrusts towards Caen and Lion sur-Mer had stalled, prompting them to give up on their plan to link up with Canadian troops fighting in the neighboring “Juno Beach” sector. Rushing through this gap, tanks and infantry of the 21st Panzer reached the coast intact.

“The future of Germany may very well rest on your shoulders,” a senior officer had told their commander, Colonel von Oppeln-Bronikowski. “If you don’t push the British back, we’ve lost the war.”

But the 21st Panzer would find it difficult, if not impossible, to prevail. At 6 pm, von Oppeln-Bronikowski’s men were horrified to see a swarm of Allied transport aircraft tugging gliders headed in their direction at 6 pm. Afraid that his unit would be cut-off by gliders landing all around them, Oppeln-Bronikowski called a retreat. Caen, however, would remain in German hands for the next five weeks, becoming a thorn in the Allied side and costing the lives of thousands of troops.

The above map was arduous to make, in that it took nearly 10 hours to produce. Instead of separating the various component actions of June 6 into three entities — the airborne landings, the main beach assault and the push inland and the German counterattack — I sought to encompass every aspect of the eastern British sector into a single map. However, in comparison to my map of “Utah” Beach which can be found further below, this map was also frustrating to create because of a paucity of information.

For example, I did not have the luxury of detailed information about the drop patterns of British airborne units from official British sources — unlike the US military which liberally proffers information about the activities of the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions on Normandy’s Cotentin Peninsula.

Movements of land forces were established through careful research and by consulting several books on Normandy, specifically Georges Bernage’s Gold Juno Sword (2007).

Continue reading “Mapping Normandy: A Brief History of the Campaign”