March 2021 Update: I am pleased to announce that an updated, corrected and more comprehensive look at the battle of Normandy is now online. Find it here. It encompasses the expansion of my research into the campaign. The number of maps are now +40 (a jump from the 19 or 20 found in this post). The site also hosts hundreds of high-resolution images, including aerial reconnaissance photos from the US National Archives, all laid out in narrative form.

In the blank, unexplored spaces of the ancient world, map makers set down warnings that “here be dragons.” In the modern world, dragons might not exist but ambiguity does.running

When an associate recently suggested a quartet of books revisiting the battle for Normandy for the upcoming 75th anniversary of D-Day in June, I realized that I had no desire to add to the existing span of literature on Normandy. To do so felt trite, conventional and despite the overwhelming heroic mythos of the campaign, boring, because it meant retreading ground already explored at length but hundreds of writers since 1944.

While I may be incapable of adding words, I have no compunction about adding art pertaining to the battle, and especially maps, because here is a medium capable of heightening clarity and through which a modicum of originality can be achieved even though the places have all been mapped a thousand times before since early humans began to wonder about the world around them, recording the lines, culverts and rises made by people and nature alike on parchment in order to quash our fear of the unknown. Swords and arrows, it turns out, are not the only ways to kill dragons. Structure and knowledge are equally potent.

For me, map-making, like music, is another form of communication, using a language made up of lines, hues and symbols to tell a story. Maps are meant to be things of precision and when they work, they invite the viewer to explore the world set in pixel or ink before them, allowing us traverse a landscape in our imagination and wonder what happened here or there.

Below follow my attempts to map the most important events in the three-month slog which constitutes the battle for Normandy. I have given myself until January 31st February 10 to complete the series in order to start an unrelated photography project on living spaces on the Indian subcontinent, partly inspired by the work of the living British artist, Doreen Fletcher, who paints the neighborhoods of London’s East End, even as gentrification threatens to expunge the character of the place. (Check out her work; it’s interesting)

In any case, here are the maps, with a handful of pertinent photographs and my thoughts. If you have comments or criticisms to make, I’m open to hearing them.

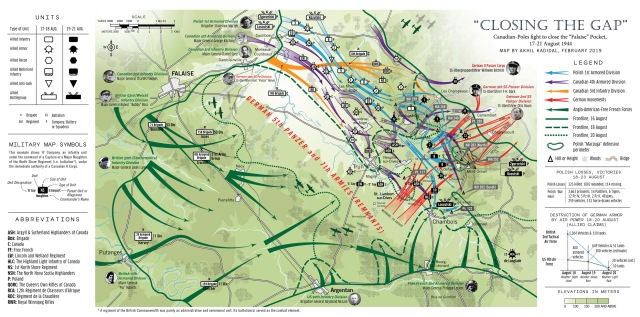

The below map, titled “Closing the Gap,” while posted out of chronological order in the following series, is possibly my favorite, with my dispensing of the usual NATO-style military symbols which are a staple of battle maps in favor of a self-devised system of icons and glyphs intended to compact unit designations. I think the end result is more attractive and effective in the way it conveys information.

Building on the work of Major C.C.J. Bond, late of the Canadian Army, whose work was published in the official “The Victory Campaign,” Part III, this map includes research from several sources, including Terry Copp’s Fields of Fire (2003). I was particularly interested in analyzing the travails of the Free Polish Division around the town of Falaise (depicted using blue arrows) whose contributions have been largely ignored by postwar historians. The included figures of German motorized transport and tanks claimed as destroyed by the Allied air forces can be misleading in that claims by pilots often did not mirror reality. In fact, the Germans lost 133 tanks (most of which were abandoned), 701 “soft-skinned” vehicles and 51 guns in the so-called “Falaise Pocket,” in contrast to claims by pilots that they had blown up 6,251 vehicles within the pocket.

![]()

An Overall look at Operation “Overlord”

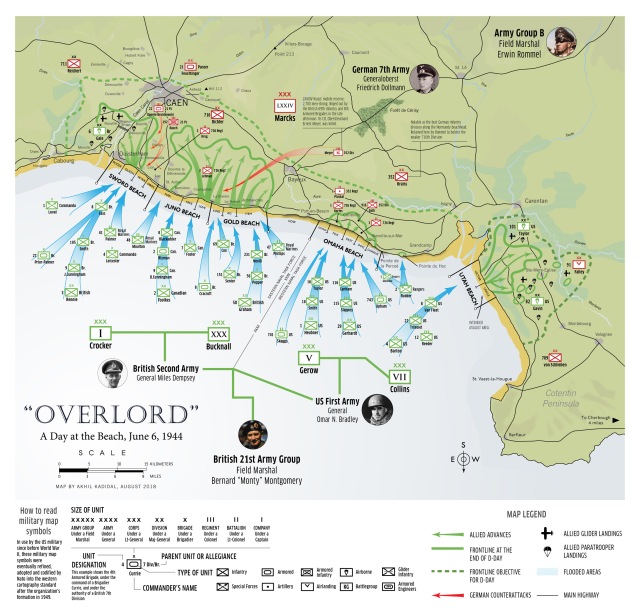

The prospect of returning militarily to France sent the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill into paroxysms of fear and dread, haunted as he was by the specter of another “Dunkirk.” For years, he had put off a cross-channel invasion of western France by cajoling and manipulating the Americans into participating in military expeditions in the Mediterranean intended to take the Allies into Germany through the soft, underbelly of Italy. By 1943, however, the Americans were of the firm belief that Nazi Germany could only be defeated through a direct assault on Hitler’s “Atlantic wall” a metaphysical entity threading from Spain to Norway. The American planners of the 1940s knew well enough that walls, no matter how thick or tall, offered no impediment to determination and a plan began to coalesce, involving pitching twelve Allied divisions (roughly 156,000 men) into German-occupied Normandy, to hew an iron beachhead from which Allied troops could range deeper into Nazi-occupied Europe.

In retrospect, Churchill’s fears seem unfounded. He spent much of June 5 and 6 in a state of unbridled inner terror, fearing that the invasion, codenamed Operation “Overlord,” would fail, dealing the western alliance with a critical setback, and forcing them to marshal manpower for another invasion in late 1945 or 1946 — by which time Hitler could have used his western reserves to smash the Soviets on the eastern front. Yet, the bulk of Germany’s forces along the Norman coast were tired, rear-echelon units with substandard equipment. The best division in the area was the 12,734-strong German 352nd Infantry Division, which had almost no combat experience (50% of its officers were green while the rank and file was largely made up of teenagers from the Hannover area). Only the presence of a hardened cadre of veterans from the Eastern Front peaked the division’s fighting prowess to acceptable levels. The other divisions were worse, with the exception of the 709th Infantry under the experienced Lt-General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, also a veteran of the Russian front.

Von Schlieben’s command, however, was less than stellar, being largely composed of men regarded as unsuitable for frontline service. The average age of a soldier in the 709th was 36 and their training had been minimal. Russian defectors padded out the infantry even though their combat effectiveness was questionable. The unit’s left flank, however, was bolstered by the 91st Airlanding Division, which although green, was better motivated and tough.

The Allied armada, which left England on June 5, would take 17 hours to cross the English Channel while Allied paratroopers flew out after dusk to secure the flanks of the invasion zone – west of the Norman capital Caen and on the Cotentin peninsula, in order to stem the flow of German reinforcements into the planned beachhead assault zone. At midnight, 13,348 Allied paratroopers began to descend onto Normandy, throwing the Germans into chaos. Then, just after dawn, at 6 am, the Allied invasion fleet hove into view off the Norman coast.

![]()

Sword Beach

A critically important sector, troops hitting “Sword” Beach were meant to roll up into the Norman capital, Caen (population 54,000), whose great road hub would have facilitated an easy advance deep into Nazi-occupied France and open the way to Paris, just 149 miles away.

The unit handed the task was the British 3rd Infantry Division, the oldest command unit in the British Army with exploits ranging back to the Battle of Waterloo in the 19th century. Bolstered by 4,000 commandos, a brigade of (212) Sherman tanks, and the paratroopers of the 6th Airborne Division on their right flank, the Third pushed ahead towards Caen on the morning of June 6, sweeping aside German resistance until the sole German armored division in the area, the 21st Panzer, placed itself between them and Caen at midday.

The 21st Panzer, once a fabled stalwart of the North African war was now a toothless tiger, replete with misfits and recruits — although 2,000 original members, having been hospitalized for wounds in North Africa two years ago, had returned to swell its ranks. Evidence of its diminished standing was borne out by the fact that it had until recently, been equipped with old French tanks captured in 1940, although by D-Day, it had been outfitted with Panzer IVs, a medium tank which was an even match for the Allied Sherman. Even its commander, Major-General Edgar Feuchtinger, behaved as though the running of this division was something of a chore, if not punishment. Accordingly, Feuchtinger spent more time lavishing attention on his mistress in Paris, than on working to get his division to full operational status. In fact, Feuchtinger was once again philandering in Paris when the invasion materialized, enraging his superior, Lt-General Hans Speidel, the Chief of Staff of Army Group B. As a chastened Feuchtinger raced back to Normandy on the afternoon of the 6th, the division activated itself and sent out patrols.

British tanks and Infantry streaming towards Caen began to take heavy fire as they reached the Periers Ridge, a stretch of high ground before the villages of Periers-sur-le-Dan and Bieville. Instead of smashing through, the British infantry of the 1st South Lancashire Regiment and the tanks of the 13/18th Royal Hussars dug in. Aside from a smattering of German infantry and strung-out screens of antitank guns, there was virtually nothing between them and the city. They could have well been in Caen by mid-afternoon. But their leader, Brigadier Edward Cass, preferring to wait for reinforcements. It would prove a fateful decision.

Meantime, senior German officers were scrambling to deploy their armored reserves scattered around central and southern France. At 9 am, nearly two hours after the beach landings, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt of OberKommando West, had attempted to rush the 12th SS (Hitler Jugend) Panzer Division and the elite Panzer Lehr Division into the invasion zone, only to be stalled by Field Marshal Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of Operations Staff in Berlin, who argued that only Hitler had the authority to move these units. But Hitler, a habitual late riser, was still asleep and would not awake before noon. When he did, he flew into a rage at the news of the Allied invasion. By when the armored units finally began to move, it was 4 PM.

By this time, British thrusts towards Caen and Lion sur-Mer had stalled, prompting them to give up on their plan to link up with Canadian troops fighting in the neighboring “Juno” sector. Rushing through this gap, tanks and infantry of the 21st Panzer reached the coast intact. “The future of Germany may very well rest on your shoulders,” a senior officer had told their commander, Colonel von Oppeln-Bronikowski. “If you don’t push the British back, we’ve lost the war.” Instead, the Germans were horrified to see a swarm of Allied transport aircraft tugging gliders headed in their direction at 6 pm. Afraid that they would be cut-off by gliders landing all around them, Oppeln-Bronikowski called the retreat. Caen, however, would remain in German hands for the next five weeks, becoming a thorn in the Allied side and costing the lives of thousands of troops before it eventually fell.

This map was arduous to make, in that it took nearly 10 hours to complete, because instead of separating the various component actions of June 6 into three entities — the airborne landings, the main beach assault and the push inland and the German counterattack — I sought to encompass every aspect of the eastern British sector into a single map. However, in comparison to my map of “Utah” Beach which can be found below, this map was also frustrating to make because of a paucity of information.

For example, I did not have the luxury of detailed information about the drop patterns of British airborne units from official British sources — unlike the US military which liberally proffers information about the activities of the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions on Normandy’s Cotentin Peninsula. Movements of land forces were established through careful research and by consulting several books on Normandy, specifically Georges Bernage’s Gold Juno Sword (2007). The resulting map, I hope, offers a clear picture of events in the “Sword” sector, although, given its complexity, I feel myself searching for Waldo.