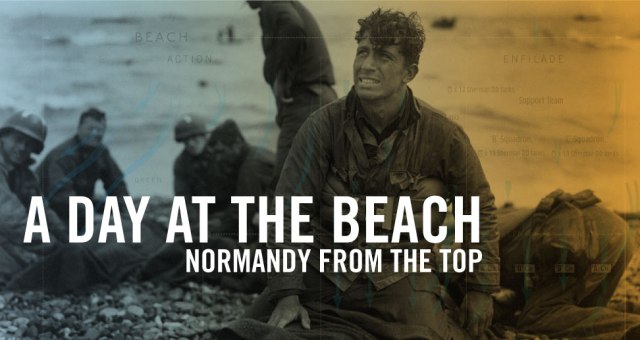

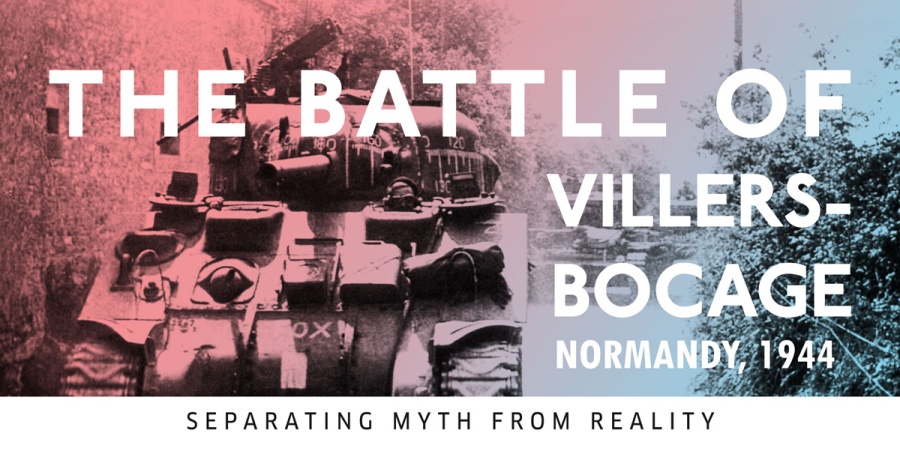

When the British landed in Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944, they had one primary objective: seize the key city of Caen from where William the conqueror had sailed for England nine centuries ago. Apart the symbolic victory to be had from seizing Normandy’s capital city, Caen offered the Allies a base from where they could launch deeper offensives into France. Unfortunately, the frontal advance was held up a German Panzer division on D-Day and so a murderous slog began. Frustrated, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery planned to outflank the enemy using his best divisions. In the lead was the veteran British 7th Armored Division, famed as the “Desert Rats” for having cut their teeth in North Africa.

Initially, all went as planned but when the British came upon the unremarkable town of Villers-Bocage, 12 miles from Caen and 20 miles from the beaches, fortune began to turn against them. Even as the “Desert Rats” occupied the town and prepared to consolidate their gains, the Germans attacked — setting the stage for one of the most controversial battles of the Normandy Campaign.

BY AKHIL KADIDAL

BY AKHIL KADIDAL

The long column of British tanks and light armor crept up along the gently slanting Norman highway under the stiff early-morning sun and came to a gentle stop by the side of the highway. Nearby, barely two hundred yards away, sheltered beyond a tall line of trees and hedgerows, the crew of a German Tiger tank gaped in astonishment. Even as they watched, a sea of khaki figures enveloped the highway, smoking insouciantly and brewing up tea. SS Oberstrumfuhrer (Lieutenant) Michael Wittmann was furious. True, he had been told to expect a British probe in the area towards the direction of the strategically-important city of Caen about a dozen miles to the east, but not so quickly and not without warning. And now the British appeared to be relaxing, even settling down for the day.

“They’re acting as if they’d won the war already,” muttered Wittmann’s gunner, Corporal Balthazar “Bobby” Woll.

Wittmann glared. “We’re going to prove them wrong.” Leaving three Tigers to guard his flanks, Wittman thundered onto the highway, guns blazing, to begin one of the most daring — and controversial tank actions of the war.

BITTER FIGHTING ON D-DAY

BITTER FIGHTING ON D-DAY

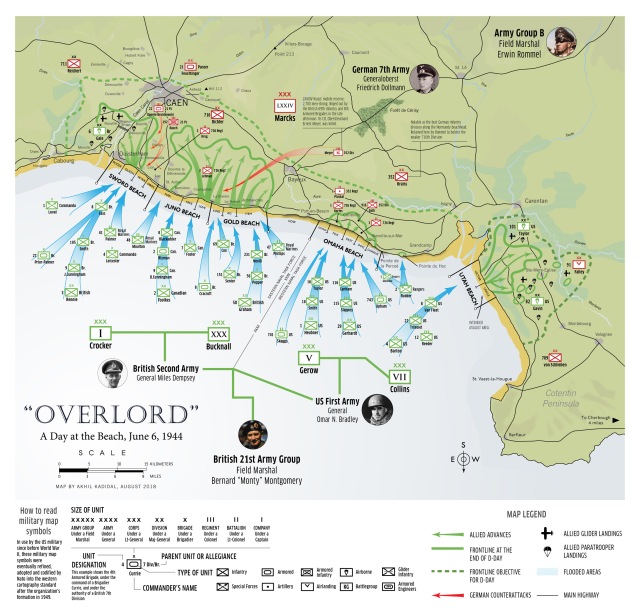

As D-Day came on June 6, 1944, men from the British 3rd Infantry Division sloshed upon the soft, sable-like sand of a beach in occupied France codenamed Sword with a singular mission: push inland and capture the Norman capital of Caen by nightfall.

For this task, the division had been outfitted with eight infantry battalions, plus engineers, specialist troops, commandos and Royal Navy men, all backed up by three armored regiments equipped with amphibious Sherman DD tanks in an independent armored brigade.[1] They were a force to contend with. The 27th Independent Armored brigade alone had a standard strength of 190 medium tanks and 33 light tanks, making it a match for a German Panzer division.

Initially all went well. Compared to the deadly fighting in the American Omaha beach sector to the west and the Canadian Juno sector just a few short miles to the right, German resistance at Sword was surprisingly light. Most of the opposition in the sector came from the German 716th Division, a poorly-equipped, depleted coastal division under a scarred-face Major-General named Wilhelm Richter. In fact, the only serious predicament facing the equipment-laden British troops was how to wade ashore in four feet of thick, cold water while clinging on to ropes running out to the beach. Still, by 11 AM, three infantry battalions had assembled inland, past the beach and had set up a divisional headquarters at the village of Hermanville. Now the troops set about trying to get to Caen. The KSLI, or otherwise the King’s own Shropshire Light Infantry, a mouthful for a non-Englishman, led the way, accompanied by several Shermans from the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

Both infantry and the tankers were in good spirits. The Sherman DD tanks of the Staffordshire Yeomanry Regiment had landed properly, better than on exercises and the tank crews had even taken the time to boil some hot cocoa on the beach. But already, events had started to move beyond the control of the British. On the KSLI’s flank, the 1st Suffolk Regiment had come up against two major German defensive points codenamed Morris and Hillman and like a whirlpool, these sucked in more and more units from the assault force. Even worse, as Lt-Colonel F. J. Maurice of the KSLI discovered, much of the Staffordshire’s tanks had become embroiled in traffic jams on the beach and the infantry was ordered to move on foot with the promise that the rest of the Shermans would arrive soon.

But Morris and Hillman had become thorns on the sides of the advance. Morris only fell at 1 that afternoon. Hillman held out until the evening, causing heavy casualties to other regiments trailing after the KSLI. At Biéville, the KSLI’s luck finally ran out when it came up against self-propelled guns. A pitched battle erupted and just as the German guns pulled out, reinforcements arrived in the form of the German 21st Panzer (Tank) Division, hardened veterans of the fighting in North Africa. Meantime, Sherman tanks from the Canadian 2nd Armored Brigade had reached the Caen-Bayeux road by themselves, only to be recalled to the beachhead because there had been no infantry to cover them. By 6 PM, the entire Anglo-Canadian advance had stalled in the face of the panzers. The drive to Caen had been thwarted.

On the western beaches, meantime, British 50th Northumbrian Infantry Division advanced out of Gold beachhead and by nightfall reached the Bayeux-Caen road. Although short of its D-Day objectives, the division consolidated its gains, dug in and awaited reinforcements. Bayeux was found abandoned at mid-day on the next day, the 7th, but progress afterwards was slow and Caen was an ever-present reminder of lost opportunities.

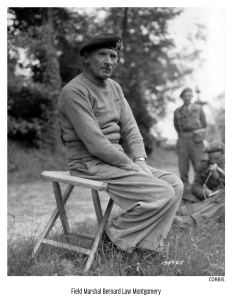

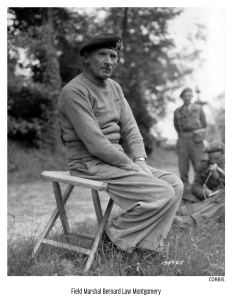

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, the commander of the British 21st Army Group pitted his men into a direct assault on the city from June 7-8. Most of his divisions inched forward but German resistance was dogged. The 50th Northumbrians kept moving southwards and pushed on for three miles towards Seulles, Longues and an inland village, Tilly-sur-Seulles. Frustrated by the slow advance, Montgomery came ashore on June 8 and set up his headquarters at the Chateau de Cruelly only to discover the tactical situation was markedly different than what he had envisaged.

His lead divisions had been in constant contact with the enemy for two days non-stop, and were visibly tiring. The prospect of capturing Caen or even breaking southwards seemed to grow more remote by the hours. Worse still, the first of the elite German panzer divisions had arrived in the battlefield and were assuming positions against the highly-experienced but weak British infantry divisions, who apart from the form of a few armored brigades, were badly deprived of the heavy tank support that could only come from the conventional armored divisions still bivouacked in England.

The SS 12th Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth) Panzer Division, with as many seasoned veterans as fanatical teenagers within its ranks, deployed across from the British I and XXX Corps, south of Bayeux, and prepared to fight it out till the end. On the east flank, the 21st Panzer had been holding the line despite efforts by the Staffordshire Yeomanry and the 3rd Division to break through. Montgomery quickly grasped that an offensive against these two first-class divisions would spell disaster for his tired troops. Instead, he decided to outflank them — outflank them as his old enemy, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel of the Afrika Korps, had repeatedly outmaneuvered the British 8th Army in North Africa two years before until there was no more desert to flank at a lonely railhead in Egypt called El Alamein. Now, the roles had been reversed. Montgomery wondered if Rommel, (now in command of Army Group B on the other side of the line) had noticed.

In a letter to the Military Secretary at the War Office on June 8, Montgomery wrote: “The Germans are doing everything they can to hold on to Caen. I have decided not to have a lot of casualties by butting against the place. So I have ordered the Second Army to keep up a good pressure at and to make its main effort [in a flank] towards Villers-Bocage and Evrecy, and thence southeast towards Falaise.”

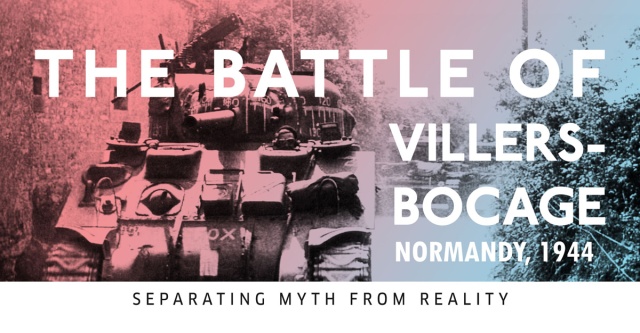

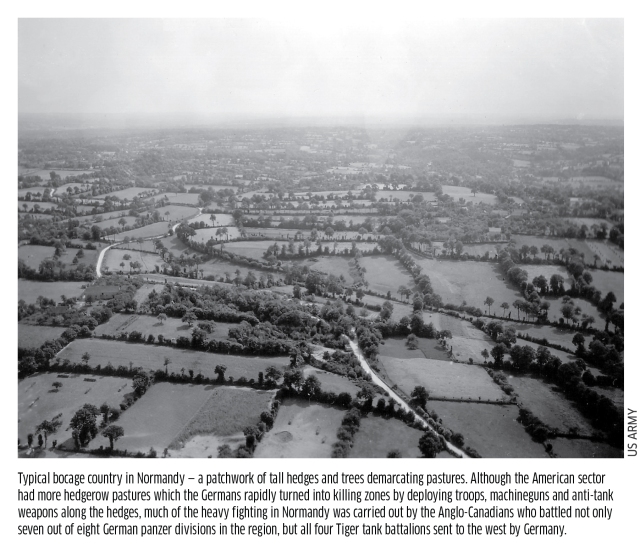

Much of the German tank opposition at this stage of the fighting was of the form of the old Panzer Mark IV, albeit upgraded and an even match for Sherman and Cromwell tanks. The 75mm cannon-armed Sherman DD’s of the 27th Independent Brigade had fared well against such opponents, inflicting heavy losses to the 21st Panzer Division from June 7 to 8th. Consequently, several senior Allied officers wanted the tanks to get on by themselves and forge the lead in some sort of armored schwerpunkt. The British 8th Armored Brigade which had landed on Gold with the 50th Northumbrians, attempted to do just that, driving into the Norman interior. They were quickly frustrated by hedgerow-heavy terrain, poor visibility and Germans wielding portable anti-tank weapons.

Tank commanders became especially wary of snipers and of Panzerfaust 30s, a short-range throwaway hollow-charge rocket which could punch through 200mm of armor (the Sherman Mk V’s maximum armor was 76mm – in the turret). Even worse, the weather was turning sour, and in any case, Montgomery could not advance over the next few days without the benefit of air support which had only one in three days of clear weather. At this critical moment, when the Germans were disorganized and partly clinging to the notion that the main assault would fall in the Calais area of France, the British could not proceed because of the weather.

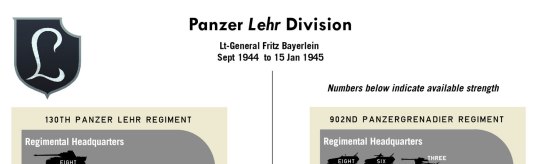

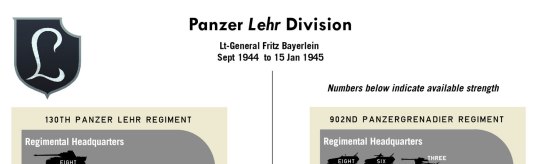

The loss of momentum began to work for the Germans who used the respite to usher in fresh divisions from the south. One was the 130th Panzer Lehr Division under an old desert hand, Lt-General Fritz Bayerlein, one of Rommel’s former staff officers in North Africa. Although untested, the Panzer Lehr was considered an elite formation because of its high level of training. Accordingly, it was equipped with the best equipment Germany could provide, including 99 Mark IVs and 89 Mark V Panthers, arguably the finest medium battle-tank of the war.

Order of Battle, The Panzer Lehr Division

On the evening of June 9, the division moved into the line near Tilly-sur-Seulles after a trying 90-mile drive from Chartres, during which it had been repeatedly attacked by Allied fighter-bombers, resulting in the loss of 130 trucks, five tanks and 84 self-propelled guns. Ailing under the loss of its support vehicles, the division nevertheless joined the 21st Panzer and the SS 12th Hitler Jugend in forming an armored shield around Caen along with the remnants of the various static infantry divisions.

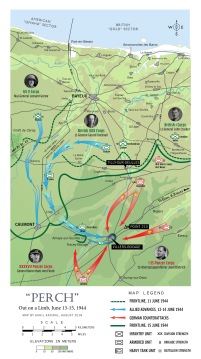

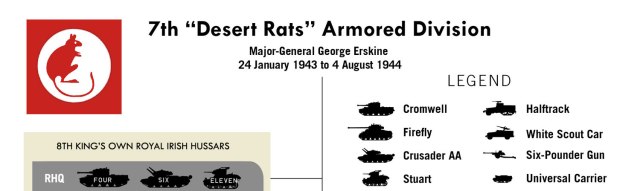

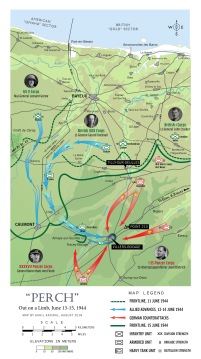

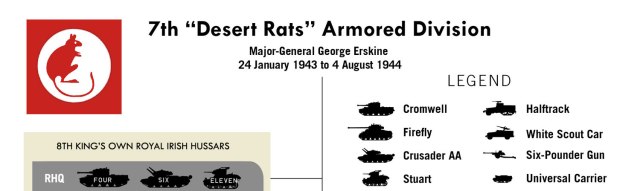

Meantime, the commander of the British Second Army, Lt-General Miles Dempsey, who had originally foreseen that Caen might not be taken easily, fell back on a contingency plan. He proposed executing Operation Perch, a wide flanking drive west of Caen of XXX Corps to Tilly-Sur-Seulles and then on to Mont Pinçon, a 1,183 foot mountain 20 miles southwest of Caen. Montgomery wholeheartedly agreed. This was exactly the sort of flanking maneuver that he wanted. British reinforcements, notably in the form of Maj-General George “Bobby” Erskine’s 7th Armored Division (famed as the “Desert Rats,” having made their reputation defeating Rommel in Africa) had begun landing at Gold beach from the evening of June 6, giving Montgomery enough forces to conduct a bold dash.

By the evening of the 7th, the division’s 22nd Armored Brigade had landed in its entirety but it was not until June 12 that the accompanying 131st (Queen’s) Infantry Brigade arrived. The division, long used to the sprawling wastelands of the desert, was taken aback by the close-quartered nature of Normandy. Massive bocages (hedgerows), towering nearly twelve feet high bordered every field, road and track behind which an entire German regiment could have lain in ambush. On one occasion, a British tank commander in the 5th Royal Tank Regiment was forced to fight off German infantrymen who leapt onboard his tank from several high embankments. Nevertheless, Montgomery hoped that the employment of the heavily-experienced “Desert Rats” would redress the odds on the frontline.

Initial British advances as part of Perch were already crawling to a halt in the face of fierce resistance from the Panzer Lehr around Tilly. Frustrated, Dempsey and his staff proposed an even more ambitious plan, codenamed Wild Oats, in which they suggested sending the armored forces in a quick dash west of Caen where they would be met south of the city by the British 1st Airborne Division and to the east by the 51st Highland Division, another veteran from out of Africa, effectively encircling the city. It was a radical plan which contained as much chance of dazzling success as it did failure. Unfortunately for its planners, it foundered at the office of the Allied air commander, Air Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, a martinet outmatched only by his incompetence who did not believe in parachute operations. In spite of the cancellation of the parachute drop, the army was eager to attempt the operation. Precious time, however, was wasted during the organization phase and by when Erskine’s tanks were ready, it was already June 10 and Wild Oats was starting to fade as an operation of practicality.

Initial British advances as part of Perch were already crawling to a halt in the face of fierce resistance from the Panzer Lehr around Tilly. Frustrated, Dempsey and his staff proposed an even more ambitious plan, codenamed Wild Oats, in which they suggested sending the armored forces in a quick dash west of Caen where they would be met south of the city by the British 1st Airborne Division and to the east by the 51st Highland Division, another veteran from out of Africa, effectively encircling the city. It was a radical plan which contained as much chance of dazzling success as it did failure. Unfortunately for its planners, it foundered at the office of the Allied air commander, Air Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, a martinet outmatched only by his incompetence who did not believe in parachute operations. In spite of the cancellation of the parachute drop, the army was eager to attempt the operation. Precious time, however, was wasted during the organization phase and by when Erskine’s tanks were ready, it was already June 10 and Wild Oats was starting to fade as an operation of practicality.

Fearing that the front was “congealing,” Dempsey called for the 7th Armored to be employed more actively. In a series of discussions on June 12, Dempsey, Erskine and Lt-General Gerard Bucknall of XXX Corps modified Perch. Erskine received orders to leave elements of the 131st Queen’s Brigade along with the 8th Armored Brigade at a line opposite Tilly, while taking his remaining tanks and infantry on a western flanking maneuver through a critical gap which had opened in the German lines between Panzer Lehr and the 352nd Infantry Division, before driving into the flanks of Panzer Lehr. It was a daring plan which would test the mettle of the British Army.

THE WEARY DESERT RATS

THE WEARY DESERT RATS

When asked why he had not employed his two best divisions on D-Day — the 7th Armored and 51st Highland — Montgomery had replied: “You don’t send your best batsmen in first.”

Yet, there were signs that the 7th Armored was no longer the diehard division it had been in North Africa. By when it returned home to England in late-1943, most of its men had not seen Britain since 1940. They had lost hundreds of their comrades in nearly three years of uninterrupted warfare in the Mediterranean and those that survived knew that their only reward would be more campaigning in Western Europe. The veterans were of the firm opinion that they had already done their bit even as other divisions had spent those war years training in the comparative safety of England. Now it was time for the rest of the army to step up.

Erskine was aware of this sentiment but the problem of maintaining discipline became difficult when a large number of experienced officers and NCOs were transferred to green units in order to shore up their veterancy levels. Even more damaging to the esprit de corps of those left behind was the replacement of their trusted Sherman tanks with British-made Cromwells (in some ways a better tank), but mechanically less reliable and with a pitifully slow reverse gear.

Some of the anger was assuaged by the introduction of Sherman “Fireflies” in January 1944, a variant armed with 17-pounder (77 mm) main guns which gave the crews a better chance of knocking out members of the German “zoo” — the Panther tanks and the even more fearsome Tiger tanks which had smashed their way into Allied lore on the strength of their armored toughness and firepower during engagements in Tunisia and Sicily.

Yet, the birth of the Fireflies was no mean thing, being that it was the result of a clamor by ordinary tankers and senior officers for a better class of tank in order to arrest five years of misbegotten tank development by Britain which had resulted in some of the worst and most ineffective combat vehicles used by side during the war. Much of the desert war from 1940 to late-1942, for example, had been fought with hopelessly outclassed tanks, under-armored and mechanically unreliably, against German machines which were not only more mobile and reliable but could project a larger cannon shell at great distances.[2] A British army report in 1942 compounded the situation by claiming that armored corps needed a no bigger tank gun than the 75 mm cannon – a statement which markedly failed to take into account that the Germans might upgrade their weaponry.

Fortunately for the British, Dempsey and Lt-General Richard O’Conner of VIII Corps thought otherwise. In an influential report, they declared “17 Pounders in all forms and sabot ammunition are absolutely first rate in our priority for equipment” — a statement bolstered by the official statements of 144 tank crews who asked that the 17-pounder cannon be mated with the Sherman tank. Even Montgomery, an uniformed martinet on tank warfare, acknowledged that the “17-Pounder is most popular.” [3] For hitting power and accuracy, the gun rivaled the German long-barreled 75mm Kwk guns and the formidable 88mm cannon. There were times, however, when a round failed to penetrate the frontal armor of Tigers and Panthers and its accuracy fell off noticeably at over a thousand yards.

The fact the gun had been designed as a high-velocity anti-tank weapon was also important. It could barely accommodate lower velocity HE shells for use against infantry and this delayed its employment for much of 1944 until a solution was found in September. In the interim, when Fireflies went to Normandy in June, they numbered only four tanks in each armored squadron — or one Firefly in a troop of four tanks. There were only 84 Fireflies in Normandy on June 11, 149 by the end of the month, and 235 by the end of July.

With time already wasted over Wild Oats, Dempsey visited Lt-General Gerard Bucknall of XXX Corps on June 11 to goad him into action. Back at the front, Erskine was frustrated at the lack of proper orders. Convinced that Perch should have gone into action a day earlier, he had privately raged at the lethargy of headquarters but now that orders had finally come through, he went to the task with glee, certain, as he later told his superiors, that there would be no “serious difficulty in beating down the enemy resistance.” His intended goal was to go roaring through a gap in the German lines between Caumont and the unremarkable town of Villers-Bocage which the Germans had been trying to plug with elements of the 2nd Panzer and SS 17th Panzergrenadier Divisions which had been delayed in transit. Finally, at mid-day on June 12, Dempsey made an important decision. A 7th Armored report summed up the choice:

Because of the difficulty of the terrain and resulting slow progress…the 7th Armored would Division would attempt to turn the enemy position on the left of the American sector. The Americans were already to the north of Caumont and there was a chance of exploiting a success towards Villers-Bocage and if possible to occupy Hill 113.

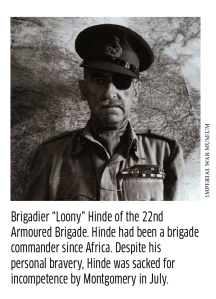

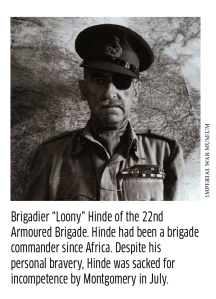

Speed and aggressiveness were of paramount importance. The unit given the job of “rushing” the gap was the 22nd Armored Brigade under Brigadier Robert “Loony” Hinde who had earned his nickname through his sometimes bewildering interest in the local flora and fauna, and because of a somewhat reckless disregard for his own safety.

Once, amidst a heavy battle he paused to examine a caterpillar. “Anybody got a matchbox?” he asked, excited. When an annoyed Lt-Colonel Michael Carver, DSO, MC of the 1st RTR suggested that this might not be the best time to go bug-hunting, Hinde exploded: “Don’t be such a bloody fool, Mike. You can fight a battle every day or your life, but you might not see a caterpillar like that in fifteen years.”[4] Other officers remembered how on many occasions, they had to warn forward units not to automatically fire on vehicles beyond the main advance as the brigadier was ahead of them.[5] Hinde’s personal bravery was without question but his tactical grasp was less than stellar since Africa.

Once, amidst a heavy battle he paused to examine a caterpillar. “Anybody got a matchbox?” he asked, excited. When an annoyed Lt-Colonel Michael Carver, DSO, MC of the 1st RTR suggested that this might not be the best time to go bug-hunting, Hinde exploded: “Don’t be such a bloody fool, Mike. You can fight a battle every day or your life, but you might not see a caterpillar like that in fifteen years.”[4] Other officers remembered how on many occasions, they had to warn forward units not to automatically fire on vehicles beyond the main advance as the brigadier was ahead of them.[5] Hinde’s personal bravery was without question but his tactical grasp was less than stellar since Africa.

He scrabbled together a battlegroup comprising the 4th County of London Yeomanry Armored Regiment (4CLY, nicknamed the “Sharpshooters”) together with infantry and reconnaissance elements of the 1st Rifle Brigade, and sent them rushing towards Villers-Bocage at about the same time as a German Tiger tank unit started filtering into the sector from the east.

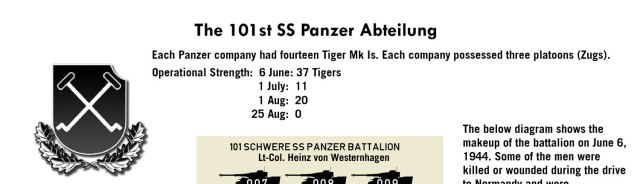

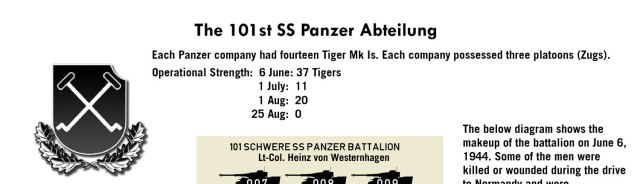

Originally stationed at Beauvais, the 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion under SS Obersturmbannführer (Lt-Colonel) Heinz von Westernhagen, had received orders to move to the front on June 6. With an established strength of 45 Tigers, it set off in the early morning hours of June 7. Much of its officers were men were veterans of the Eastern Front. Westernhagen had been severely wounded during the battle at Kursk and had only rejoined the battalion in February. One of his subordinates, Lt. Michael Wittmann of the 2nd Company had amassed a tally of over 100 tank kills during his time in Russia and the commander of the 1st Company, Rolf Möbius, was also a budding panzer ace who would be credited with destruction of more than a hundred enemy tanks during the war.

At 3 AM on the morning of June 7, the Tigers passed through Gournay-en-Bray and made for the Seine River. They passed through Paris on June 8 but as they reached Versailles, Allied fighter-bombers struck. Several Tigers were damaged or knocked-out with nine men killed and eighteen wounded. Dispersing to mitigate further casualties, the battalion would not reach Villers-Bocage until the evening of June 12, where they parked under the shady recesses of small woods south of the main highway, N175. Exhausted by five nerve-wracking days on the road, they collapsed into a stupor on the ground beside their Tigers, too weary to even reconnoiter the ground ahead.[6]

The British meantime, had been making steady progress. On the afternoon of June 12, the “Desert Rats” bypassed Tilly and swung westwards before moving along on a southeast arc. The advance was largely uneventful until the 22nd Brigade’s Cromwells encountered and knocked out a German Panzer IV at a hamlet called Jerusalem. The recce tanks of 11th and 8th Hussars relentlessly probed the German lines for a weakness. The Third Troop of A Squadron of the 8th Hussars eventually found it, but lost two Cromwells in the process, including the troop leader, Lt. Talbot-Harvey, who was posted as missing.

Then at 4 PM, during the approach to Livry, a German anti-tank gun knocked out a Cromwell from the Kings Royal Irish Hussars (KRIH), killing two of the crew. A German soldier with a panzerfaust then scored a direct hit on a Stuart light tank from same unit, blowing it up. Further advances by the Hussars were repelled with additional losses in tanks. The delay was temporary however, and the “Rats” smashed up the road with the full strength of the 22nd Armored Brigade. Livry fell, and with darkness closing, the British set up camp for the night.

The bright red hue of fires from Caumont in the west, ablaze with American shelling, illuminated the night. But on the other side, to the southeast, towards Villers-Bocage, was a strange ethereal darkness that was the German lines. The “Rats” closely observed this darkness. From their forward positions, a mere six miles separated them from Villers-Bocage and an engagement with history.

Troops of the 1st Rifle Brigade search German prisoners near Tilly-sur-Seulles on 13 June 1944.

Stuart tanks of 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars, 7th Armoured Division, 15 June 1944.

Sherman tanks move up past a crash-landed Spitfire, while advancing on Tilly-sur-Seulles in June 1944.

FATEFUL ENCOUNTER

FATEFUL ENCOUNTER

Early, at 4.30 on the morning of the 13th, Brigadier “Loony” Hinde started up the brigade. There had been some light rain the night before and everything was moist. A Rifle Brigade officer, Lt. Bruce Campbell of A Company’s 2nd Platoon, went up to a Cromwell which had occupied a crossroads outside Livry and asked the commander if he anything was amiss. The commander replied that there had been quite a lot of firing in the town during the early hours but that it had died down since. Worried that the Germans had recaptured Livry, Campbell mounted an immediate recce into the town, only to find empty streets. He reported that Livry was still clear and concluded that the Cromwell commander must have referred to all that American firing at Caumont the night before.

So the division started off again, the unison of engines shattering the morning calm. The “Desert Rats” had an armored strength of 210 Cromwells, 44 Stuarts and 36 Shermans, but the forward pincer forging on towards Villers-Bocage comprised only the armor of the 4th CLY accompanied by the 1st Battalion of the Rifle Brigade Regiment (a misnomer if there ever was one) and the 5th Royal Horse Artillery — accounting for 55 Cromwells, six Sherman Fireflies, 11 Stuarts, five Centaur AA tanks (which never entered town), eight Daimler Dingo armored cars, two to three Observation tanks of the 5th Royal Horse Artillery, six 6-pdr guns and six 3-inch mortars.[7]

Wary of what lay ahead, the 4th CLY’s commanding officer, Lt-Colonel William Arthur Onslow, the Viscount Cranley, MC, asked for a reconnaissance of the roads ahead as German scout cars had been spotted observing the routes south from Tilly.[8] Hinde demurred, anxious to push on without delay in order to keep the German armor away from the Americans at Caumont.

Moments later, Lt. Charles Pearce, the liaison officer of the 4th CLY’s Regimental Headquarters Troop, riding in a Humber scout car behind the leading Cromwell of the troop, saw one of these German scout cars for himself. It was an eight-wheeled German Sdkfz shadowing the convoy from an orchard to the left of the road. Pearce radioed an urgent warning to the RHQ leader, Major Arthur Carr, only to discover that Carr had so overburdened his Cromwell with kit that it could not even turn its turret target the enemy. The next tank in line, commanded by Lt. John Cloudsley-Thompson, moved to attack, but by the time it could get into position, the German had vanished.

Jarred by these encounters, the regiment continued on. As they clattered up the highway, a great winding road flanked by Chestnut trees, nerves were on high alert. Tension, however, was counteracted by droves of local farmers and villagers who emerged from the many farms and hamlets along the way, bearing presents of fruit and wine. Several British officers took this opportunity to gain raw intelligence from the locals about German dispositions. It was this stage that myth and rumor-mongering began to intrude into quantifiable intelligence data. One farmer, for example, informed British officers that a German tank had been stranded without fuel at the Chateau de Villers-Bocage. Despite the salivating prospect of taking this prize, the British had no time to investigate and pressed on.

Abruptly at 8 AM, they found themselves within Villers-Bocage, surrounded by cheering locals. Several cafes opened for business and the leading British troops had the good fortune to trade their rations for fresh produce. Yet, these good spirits were not to last. By when Lt. Campbell arrived with the Rifle Brigade, many of the locals, fed by reports of German forces in the area, had simply vanished.

An hour passed before Lt-Colonel Cranley received instructions to push on up the highway towards a high ground about a mile east of town marked on maps as Point 213. Cranley was reluctant, protesting again that the area had not been reconnoitered and that his men might be out “on a limb.” Hinde was insistent. After he had made his point, the brigadier departed Villers-Bocage for his headquarters in the rear. Cranley, meantime, left four Regimental HQ tanks at the top of the main street and took A Squadron of the CLY (eleven Cromwells, four Fireflies and one command car) with the A Company of the Rifle Brigade to Point 213.[9] They reached the place easily enough and set up a rudimentary bivouac along the length of the arrow-straight stretch of the N175. Caen was just twelve miles away. Wittmann’s Tiger Company was 200 yards away.

Back at headquarters, Montgomery was signaling the news to his deputy, Major-General Freddie de Guingand in England: “So my pincer movements to get Caen in taking good shape, and there are distinct possibilities that the enemy divisions may not find it too easy to escape, especially Panzer Lehr.”

Back at headquarters, Montgomery was signaling the news to his deputy, Major-General Freddie de Guingand in England: “So my pincer movements to get Caen in taking good shape, and there are distinct possibilities that the enemy divisions may not find it too easy to escape, especially Panzer Lehr.”

Meantime at Point 213, several Rifle Brigade officers were summoned back into town to receive new orders from Major James Wright, the CO of the Rifle Brigade’s A Company. A half track was sent to collect them, but someone had the presence of mind to point out that concentrating all officers in one vehicle was a mistake and so three halftracks went. While this conference was going on, the rest of troops at the Point were placed on standby. Suddenly Lt. Bill Garnett, a troop leader in A Squadron, at the head of the column, spotted a German staff car on the highway. He opened up with his Besa machinegun and saw the car go spinning away into a field and catch fire. After this short excitement, the column parked itself on the highway shoulder and allowed itself to be overtaken by a general atmosphere of insouciance.

Nine Rifle Brigade halftracks that had not been used by the officers waited in a neat column by the right-hand side of the road as an artillery Observation Post (OP) Cromwell, commanded by Captain Roy Dunlop from the 5th RHA clattered up the road to join A Squadron.[10] At the tail end of the Rifle Brigade, an anti-tank section under the command of Lt. Roger Butler with four Loyd carriers and about three guns deployed near the Tilly junction where a Calvary stood. The area was not secure, but this did not deter the crews from leaving their tanks and vehicles for a spot of morning tea and banter. The riflemen posted sentries but none of them could see more than 250 yards on either side of the highway.

By now, a long column of traffic had developed behind the vehicles of the Rifle Brigade. Immediately behind were three Stuarts of the 4CLY’s Reconnaissance (Recce) Troop, and behind that, in the town itself was the Regimental Headquarters (RHQ) Troop on the main street, Rue Georges Clemenceau. The regiment’s B Squadron was deployed near the Jean d’Arc intersection at the western proximity of the town, while C Squadron was on the outer western edge of Villers-Bocage. The rest of the “Desert Rats” were still further behind, near Tilly or Livry.

Within Villers-Bocage, a 2 Troop, B Squadron Firefly commanded by Sgt. Stan Lockwood took up station at the Jean d’Arc intersection. One of his comrades, Sgt. Wally Allen, a Cromwell commander from 1 Troop parked his tank nearby and walked over to have a chat. As the smells of a pastoral French village swam in the air, Allen commented about the smell of baking bread from one of the nearby shops. Up above them, the sky was wonderfully blue. The war seemed a hundred miles away.

But near the point, Wittmann, standing atop his turret, studied the panoramic view. Both the town and the rising highway were seemingly packed with British vehicles of all types: Sherman Fireflies, Cromwells, Stuart tanks, halftracks and several towed anti-tank guns. The Germans were well inside Cranley’s forward screen and Wittmann stood to mount the only opposition to the British in their drive eastwards. Yet, he was hardly ready to act. For one, the bulk of the 101st SS Panzers had not arrived. Ten Tigers from SS Captain Rolf Möbius’s 1st Company were ten miles to the east, beset by irritating mechanical problems. The 3rd Company was even further away, near Falaise and would not reach the Villers-Bocage front until two days later.

Wittmann’s company was still trying to recover from the trials of the journey from the north. To exacerbate matters, the Tiger, although a formidable tank, had teething mechanical problems. Despite the official establishment strength of 15 Tigers in the 2nd Company, only six of Wittmann’s Tigers had reached the battlefield. Upon arrival, Wittmann’s own tank (No. 205) had broken down because of a transmission a problem, and then Lt. Wessel’s machine (No. 211) had gone to Panzer Lehr headquarters to establish contact with that division. To compound matters, a third Tiger (No. 233) under Sgt. Lötzsch had damaged a track and a fourth Tiger (Sgt. Stief’s No. 234) had an overheating engine. This left just Lt. Hantusch’s Tiger 221 and First Sergeant Kurt Sowa’s Tiger 212 ready for action.

Commandeering 212, Wittman, together with his gunner, Corporal Balthazar “Bobby” Woll, an old comrade from the Eastern front, Wittmann decided to attack. “I had no time to assemble my company,” he later said. “…I had to act quickly, as I had to assume that the enemy had already spotted me and would destroy me where I stood. I set off with one tank, having given the others orders not to retreat but to stay where they were and hold their positions.”

Commandeering 212, Wittman, together with his gunner, Corporal Balthazar “Bobby” Woll, an old comrade from the Eastern front, Wittmann decided to attack. “I had no time to assemble my company,” he later said. “…I had to act quickly, as I had to assume that the enemy had already spotted me and would destroy me where I stood. I set off with one tank, having given the others orders not to retreat but to stay where they were and hold their positions.”

At 9.05, he burst out of his hiding place and clattered towards the N175. Up until this point, the British had been oblivious to the presence of the Germans but when Wittmann turned into the highway, a Sgt. O’Conner of the Rifle Brigade who had been travelling towards Point 213 in a halftrack, saw him and broke radio silence to announce the danger: “For Christ’s sake get a move on! There’s a Tiger running alongside us 50 yards away.”

“Don’t worry it’s one of ours,” replied Lt. Alfred “Alfie” de Passe, a Rifle Brigade officer further down the highway.[11] He was mistaken. O’Conner’s warning was the first the British would receive of the attack. It was already too late.

An 88mm shell punched into a Cromwell which was attempting to position itself.[12] Captain Christopher Milner, the Rifle Company’s second-in-command, had just passed the tank when it appeared to come apart at the seams. Almost immediately, Milner seemed to be seeing Tigers all over the area. A second Tiger had appeared from beyond the trees, near the town, its guns belching flames. To the north, a third was spotted.

An 88mm shell punched into a Cromwell which was attempting to position itself.[12] Captain Christopher Milner, the Rifle Company’s second-in-command, had just passed the tank when it appeared to come apart at the seams. Almost immediately, Milner seemed to be seeing Tigers all over the area. A second Tiger had appeared from beyond the trees, near the town, its guns belching flames. To the north, a third was spotted.

A formidable Sherman Firefly, the only tank which could have defeated Wittmann’s ambitions at this critical stage, rumbled on to the center of the highway and began to turn its turret. A second later, a German shell tore through it with a deafening crack, blowing up the machine whose wreck now blocked the highway to Point 213.

Lt. Campbell and two of his subordinates, Lt. Coop and Sgt. Gale, had been driving back towards the point when a large-caliber shell roared by towards another Cromwell deployed on the side of the road. They watched in horror as Wittmann’s Tiger clambered up on the highway and began raking the Rifle Brigade’s vehicles with gunfire. Campbell’s halftrack veered left towards the Point and escaped danger.

A rifleman attempted call up Major Wright to warn him about what happening, only to have Wright tersely tell him that knew he that “they were all around us.” Complacency with the knowledge of the threat would not help the British, and the light-skinned carriers and half-tracks began to erupt into flames along the length of the highway as horrified riflemen scrambled away, desperate trying to reach cover. Lt. de Passe, who had earlier so cavalierly dismissed the warning, was now killed when he scrambled up onto his halftrack to get a PIAT (a shoulder-mounted anti-tank weapon).

Wittmann recalled that “there was unbelievable confusion among the enemy.” Yet for the tumult of war and explosions there were surprisingly little casualties. To be certain, nearly all of the Rifle Brigade’s vehicles were on fire. Milner, later recalled that, “the enemy attended first of all to the three motor platoons by….trundling back towards Villers, shooting up vehicles and riflemen section by section, with only the company’s two 6-pdr anti-tank guns able to offer even a measure of resistance, which I learned afterwards they did with considerable bravery but with little effect.” True, a few riflemen attempted to destroy the Tiger with their six-pounder (57mm) anti-tank guns, but were pinned down as they tried to do so and two were destroyed by the Tiger as it rumbled by. Others ran desperately for the refuge of the woods, with gunfire ripping all around them.

Reaching the Tilly crossroads, Wittmann then came upon the three Stuarts from the Recce Troop. Woll turned the massive 88mm gun on them. To his surprise, instead of fleeing, the leading Stuart commanded by Lt. Rex Ingram bravely attempted to block the road. Woll sent it to a fiery end. A second Stuart erupted in a spectacular explosion that propelled the turret skywards. The third blew up.[13]

As the long black plumes of smoke spiraled upwards into the sky, Wittman rammed Ingram’s destroyed Stuart aside and pushed on. Aware of the danger of anti-tank weapons, he stumbled upon a halftrack belonging to the 4th CLY’s medical officer and blasted it with a round before turning his attention to a line of Cromwells on the Rue George Clemenceau. Unbeknownst to him, these were the tanks of the Regimental Headquarters.

Lt. Charles Pearce, the liaison officer who was nearby in his Humber scout car, saw the last Stuart go up in flames and attempted to warn the others, only to find the radio net swamped by frantic signals from A Squadron up at the point. Several of the headquarters men were in a state of utter bewilderment. Lt. John Cloudsley-Thompson thought that the Stuart blowing up was a tank from A Squadron. Behind him, however, Captain Paddy Victory, of the 5th Royal Horse Artillery, had been listening to the battle closely, and was in communication with Captain Roy Dunlop, his man at the point who was desperately calling for a smoke screen. When it finally became clear to the Headquarters Troop that something was terribly wrong, several attempted to back their tanks away from the main street.

Cromwells, however, had a notoriously slow reverse gear, with a ratio of only about 0.2 mph, and these attempts to get into cover were, in the words of one surviving man, “painfully slow.” Before they knew what had happened, the Tiger was among them. A flash illuminated the street as a shell blasted into Major Carr’s overburdened Cromwell at nearly point-blank range. The tank erupted into flames. Lt. Pearce, who had parked next to Carr, remembers the strike. “The flash from the 88 was terrific with a very loud bang.” A thick shock of black smoke filled the street.

Realizing that he was next on the list, Pearce ordered his driver to get them out of there. Immediately backing away and turning around, he sped on a side road back towards the intersection to summon help from B Squadron. On the way, he encountered Captain John Philip-Smith with the other half of the Recce Troop who demanded to know what was going on. When Pearce told him, Philip-Smith deftly moved his surviving Stuarts out of harm’s way.

Wittmann continued blasting the headquarters troops. In the second Cromwell, Captain Cloudsley-Thompson watched the horror approach. “Through the smoke I could make out the shape of a huge Tiger and I was not more than 25 yards away,” he said.

Wittmann continued blasting the headquarters troops. In the second Cromwell, Captain Cloudsley-Thompson watched the horror approach. “Through the smoke I could make out the shape of a huge Tiger and I was not more than 25 yards away,” he said.

Cloudsley-Thompson opened fire, but the shell ricocheted off the German machine. In desperation, he fired a smoke canister which flew past the Tiger and landed behind it. Woll methodically turned the 88mm gun on the Englishman and in the next moment, Cloudsley-Thompson heard a whoosh pass through the tank. They had been hit. A burning sensation broke out between his legs and a jet of blue flame swept through the turret. He opened his mouth to shout and found it abruptly covered with sand and burned paint.

He managed to yell “bail out,” and clambered out gasping for air, rendered nearly half deaf by the concussion. He hit the ground hard and as the rest of his crew piled out of the broken Cromwell, the Tiger’s machinegun opened up. Cloudsley-Thompson scrunched on the ground, trying to make himself a small a target as possible as bullets whizzed by and smacked into the metal of his dead Cromwell. The Tiger trundled on, blasting two more headquarters tanks.[14] A third, commanded by Captain Pat Dyas, the 4th CLY adjutant, deftly escaped by backing into the garden of a farm, the Ferme Lemonnier. Miraculously, Wittmann failed to see him and drove on. Then Cloudsley-Thompson watched as Dyas, who had been already wounded in the head by ricochet shrapnel hitting his turret hatch, emerged from the garden and crept up after the Tiger, apparently unable to initially fire because its gunner had dismounted to urinate in the garden.

Two Observation Post (OP) tanks from the 5th Royal Horse Artillery now had the misfortune of coming under the gaze of the Tiger. One was a Sherman commanded by Major Dennis Wells, which did not even possess a main gun. A piece of lumber had been attached to the turret to give it the impression of being armed. Within moments, this machine and Captain Victory’s Cromwell went up in flames.

The liaison officer, Lt. Pearce raced back towards the Jean D’Arc intersection to summon reinforcements, only to find the intersection and the adjoining streets deserted. Despondent and feeling that he had “made an appalling mistake” and come down the wrong street, he pushed on while attempting to get through to A Squadron and Cranley at the Point. Little did Pearce know that Cranley and A Squadron were already under siege by the remainder of Wittmann’s company. Then at last, Pearce spotted a lone B Squadron Firefly on a side-street.

Its commander, the 30-year old Sgt. Stan Lockwood, alarmed by the noises of gunfire and explosions, had been watching the main road with foreboding. Pearce’s scout car came racing around the corner towards him, its commander waving his arms frantically. The car screeched to a halt nearby and Pearce shouted to Lockwood to get his tank activated and attack the approaching Tiger.

Lockwood directed Pearce to B Squadron headquarters, located on the outskirts of the city, and moved forward alone to take on Wittmann. They deployed at a corner a hundred yards away and waited for the Tiger to appear.[15] Long minutes passed. Finally, succumbing to an irrepressible curiosity, Lockwood nosed the Firefly around the corner to see the Tiger still firing up the street.

Quickly, Lockwood and his crew pumped four shells at the Germans and were elated to see flames and smoke come streaming out of the Tiger. Realizing that he was under attack, Wittman turned his turret around and fired a shell at the corner house shielding Lockwood’s Firefly. In the upper floor, a German sniper who had been watching the scene felt the floors give way as the house toppled over on the British tank. By when Lockwood extricated himself from the mess, the Tiger had disappeared.

Wittman beat a hasty retreat back up the main road. At this point, in one of those remarkably personal moments of war, Wittmann stumbled upon Dyas who had been stalking him. The Cromwell’s crew fired a 75 mm round from a range of less than a hundred meters (110 yards). The round ricocheted off the Tiger’s thick hull. Frantic, Dyas got off one more round before a single 88mm shell tore into the Cromwell’s turret.

Wittman beat a hasty retreat back up the main road. At this point, in one of those remarkably personal moments of war, Wittmann stumbled upon Dyas who had been stalking him. The Cromwell’s crew fired a 75 mm round from a range of less than a hundred meters (110 yards). The round ricocheted off the Tiger’s thick hull. Frantic, Dyas got off one more round before a single 88mm shell tore into the Cromwell’s turret.

Bleeding from the nose and the ears, Dyas stumbled out of the turret ashen, followed by his driver pushing out from the front hatch. Machinegun fire erupted around them as they stumbled away from their burning tank. It is possible that Dyas mistook this for rifle fire for he later reported that he had been shot at by German infantry. A local girl helped him and the driver to safety. In a state of agitation, Dyas stumbled towards a signals tank of the headquarters troop previously disabled by Wittman.[16] Discovering that its radio was still operable, Dyas informed Cranley of the disastrous series of events which had befallen the regiment in town.

Cranley replied that he knew that the situation was desperate but that he was powerless to intervene because his own force at Point 213 was under siege by other Tigers (by now tanks of Rolf Möbius’s 1st Company had also joined in the attack). It would be the last that Dyas heard of his commander. At mid-morning, the radio at the point went off the air.

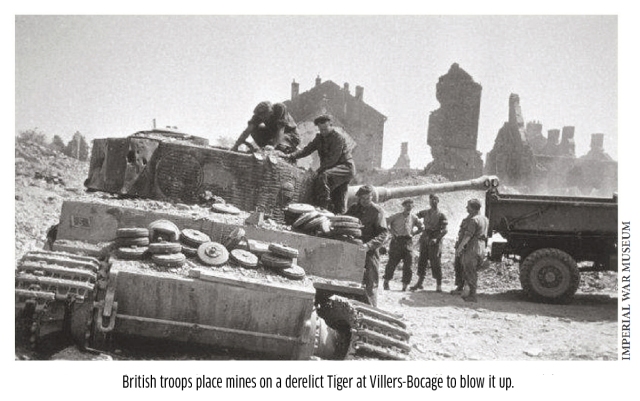

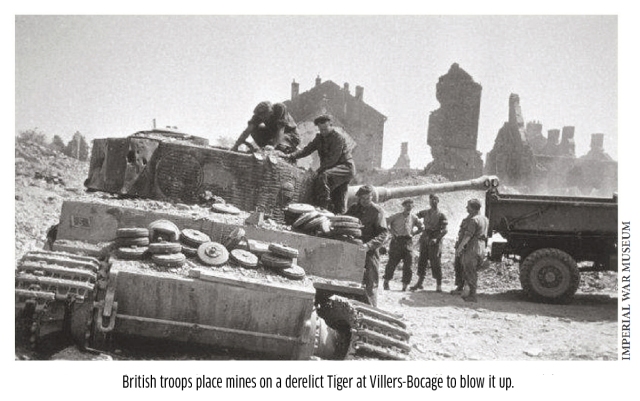

Wittmann, meantime, was in haste to escape the town but found that his luck had started to run thin. As the Tiger passed the long line of burning vehicles of the Rifle Brigade near the Tilly crossroad, it came within the sight of a single British six-pounder gun. As the tank emerged from the murky screen of swirling smoke and dust, the gun crew, commanded by a Sgt. Bray, opened fire. The shell blew off a wheel sprocket, immobilizing the Tiger. Unable to move, Wittman ordered his crew to blast everything on the road and as the British scurried for cover, the Germans grabbed their small arms and bailed out, sprinting for the safety of their own lines without losing a single man.[17]

The engagement had been a tremendous German success. In the words of the official 7th Armored Division history:

[The Tiger’s] first shot destroyed one of the Rifle brigade half-tracks, thus blocking the road; and then at its own convenience, destroyed the remainder of the half-tracks, some Honey [Stuart] tanks of the recce group, four tanks of …the Regimental HQ troop and two OP (artillery observation post) tanks accompanying the squadron. Escape for the tanks, carriers and half-tracks was impossible; the road was embanked, obscured by flames and smoke from the burning vehicles whose crew could only seek what shelter they could from the machine-gun fire, and our own tanks were powerless against the armor of the Tiger, with limitless cover at its disposal.

German propagandists and even post-war Allied historians gave Wittmann inflated credit for wiping out a full armored regiment and sometimes even a division, but his actual tally amounted to eight fully-armed medium tanks, three Stuarts, 14 carriers or halftracks, two six-pounder guns and one unarmed Sherman.

Walking back to the Panzer Lehr headquarters at the Cháteau d’Orbois some 3¾ miles (6 km) north of Villers-Bocage, Wittmann and his crew requested reinforcements to go back and finish off the British. Divisional officers readily agreed.

The remains of the Rifle Brigade’s 6-pounder section as seen from Villers-Bocage. The riflemen received much criticism for parking their vehicles so closely together. In reality there was a healthy distance between each machine.

RSM Gerald Holloway’s Cromwell

This is John Cloudsley-Thompson’s Cromwell. Considering its condition, it is remarkable that all five members of the crew survived. Much of the debris piled on the machine is the result of looting by German soldiers who investigated every hold and box.

Captain Pat Dyas’ Cromwell

Major Dennis Wells’ Sherman OP, minus its wooden cannon which lies on the ground before it.

Captain Paddy Victory’s Cromwell

REGROUPING AMID THE RUBBLE

REGROUPING AMID THE RUBBLE

Back in Villers-Bocage, surviving members of the 4th CLY were determined to repay the Germans with equal measure. But when Lt. Pearce pressed Major I.B. “Ibby” Aird of B Squadron to alert his unit for action as there was little between them and A Squadron about a mile and a half away, Aird, sitting on the turret of his Cromwell, stared wordlessly.[18] Just then, Major Peter McColl, the commander of C Squadron showed up. He demanded to know what was going on and why his squadron and the following Queens infantry were still blocked in traffic west of Villers-Bocage. When Pearce recounted the debacle, an astonished McColl barked at Aird to get cracking, and to Pearce’s surprise, Aird finally stirred and did just that.

McColl set up a temporary regimental headquarters and at this critical juncture of the battle, dispatched a set of orders which probably saved the regiment from being completely destroyed. Aird’s contribution was a suggestion to send a force of tanks and men to relieve A Squadron at the point.

By now, Cranley’s situation was dire. Despite losing three additional Cromwells to Tigers commanded by Sergeants Georg Hantusch and Jürgen Brandt, he still had nine operational tanks (including two Fireflies) but not all of his tanks had crews.[19] Worse, only a platoon-worth of Riflemen had joined him at the Point, having survived the initial maelstrom on the highway. Unfortunately, a large percentage of these men were officers — Major Wright, Captain Milner, Lieutenants Campbell, Coop and Parker —who held command over just a few fighting NCOs and 10 other ranks.

By now, Cranley’s situation was dire. Despite losing three additional Cromwells to Tigers commanded by Sergeants Georg Hantusch and Jürgen Brandt, he still had nine operational tanks (including two Fireflies) but not all of his tanks had crews.[19] Worse, only a platoon-worth of Riflemen had joined him at the Point, having survived the initial maelstrom on the highway. Unfortunately, a large percentage of these men were officers — Major Wright, Captain Milner, Lieutenants Campbell, Coop and Parker —who held command over just a few fighting NCOs and 10 other ranks.

All together the riflemen had two scout cars, three halftracks, and four motorcycles. Major Wright hoped to get a battalion of Queen’s through to them, but this was sheer fantasy at this stage. In the meantime, the platoon split into two parties. One, commanded by Corporal Nicholson took six men to the southern side of the road, while Lt. Campbell occupied the junction away from Point 213 with four men. This became “Campbell’s Corner.” Milner occupied a farm house nearby, as Sergeant Gale watched the farm track on the other side. Lt Butler conducted a one-man recce along the southern hedgerow of the field and Lt. Coop occupied a position just forward of Campbell’s corner.

Cranley, meantime, deployed his tanks as best his could. One Cromwell parked itself near the farmhouse and protected the northern flank. Three tanks waited by the highway near the house with the rest of the Rifle Brigade vehicles. From here, they decided to hold until reinforcements arrived. Cranley preferred to escape on foot after setting the tanks and vehicles on fire, but this plan was vetoed by “Loony” Hinde in distant headquarters.

At 10 AM, with the arrival of the 101st SS Panzer’s 4th Company (mostly halftracks and armored cars), the Germans began to overrun most of the isolated British tank crews and riflemen on the highway. Some thirty Rifle Brigade men evaded the Germans and made their way back to the town. They were the fortunate ones.

Units of the Panzer Lehr also entered the battle area. A patrol under a Major Werncke heard tank engines beyond a tall line of hedgerows and trees. Dismounting from his scout car, Werncke continued on foot to discover a column of Cromwell tanks whose crews and officers had dismounted and were studying a map at the head of the column. Werncke would later claim to have sprinted to one of the empty Cromwells, jumped in the driver’s seat and took off before the British could react. Roaring through the eastern end of the town, he encountered a scene of “burning tanks and Bren gun carries and dead tommies.” Werncke drove his prize pack to headquarters.[20]

Aird and McColl wanted to send in infantry to root out enemy forces within Villers-Bocage before sending in B Squadron to conduct a breakthrough, but Cranley rejected the idea. Instead, he requested a smoke screen so that units at the Point could pull out under cover. But Cranley was out of time. Minutes later, he radioed that more Tigers were attacking and that withdrawal had become impossible. Then, at 10.35, Cranley’s radio went dead. Presumably, his command had been overrun.

Actually, Cranley had planned to breakout, with or without orders. The Cromwell near the farmhouse attempted a probe north to see if there was a way out when it was knocked out by a shell from a panzer down the lane. The driver was killed but the rest of the crew bailed out and ran back to Milner’s farmhouse where the captain urged them on to “Campbell’s Corner.”

Lt. Campbell, who had seen the flash of the Cromwell’s demise, was anxious to move the surviving Rifle Brigade vehicles before they met the same fate. Major Wright’s scout car raced across 20 yards of vulnerable open ground without being hit and parked near a ditch where the wounded were being treated. Another Cromwell here decided to move on and nearly ran over some of the wounded in the process. Campbell now dashed to another ditch where Majors Wright and Peter Scott, MC, the commander of the 4th CLY’s A Squadron were firing at the Germans with two Cromwells.

The Germans soon began to bombard the point with cannon and artillery fire, hitting the trees to create tree-bursts. The British held on for four minutes before Cranley’s command began to disintegrate. The remaining tanks and infantry bolted in all directions. Major Scott and several other officers were killed and the survivors started to come out with their hands up. Many of the tankers attempted to burn their tanks to prevent them from falling into enemy hands but the Germans put a quick stop to this. About thirty men from the CLY fell into the bag as did several crews from the 5th Royal Horse Artillery.

The Germans soon began to bombard the point with cannon and artillery fire, hitting the trees to create tree-bursts. The British held on for four minutes before Cranley’s command began to disintegrate. The remaining tanks and infantry bolted in all directions. Major Scott and several other officers were killed and the survivors started to come out with their hands up. Many of the tankers attempted to burn their tanks to prevent them from falling into enemy hands but the Germans put a quick stop to this. About thirty men from the CLY fell into the bag as did several crews from the 5th Royal Horse Artillery.

Captain Milner, who had had been saved this indignity on account of his isolated location, wondered at the sudden lack of gunfire. Leaving the farmhouse he walked along a lane and made his way back to the main position where he found men in black headgear casually talking to men from his own unit. Thinking that they had been relieved by troops from the British Royal Tank Regiment (who wore black berets), Milner hurried towards them. Abruptly he realized that the men in black were Germans. Doing a swift about-face, he dived into a garden on the left. Incredibly, no had one had seen him.

The Germans rounded up some fifty members of the Rifle Brigade in total. Cranley himself avoided capture by hiding out. Milner was still in the garden when a German officer curiously began yelling: “Englishman surrender.” Afraid that he had been spotted, Milner started to move away along the hedgerow but the German seemed to be following him. Then, the German stopped on the other side of the hedgerow and started to speak with another officer by a Küblewagen.

Convinced that his time was up, Milner stood up with his Sten gun at ready, determined to mow down both Germans. Aiming at them at point-blank range, he squeezed the trigger. The gun jammed. The Germans, who were busy in a conversation, took no notice. Overcome by embarrassment as though he had interrupted a private gathering, Milner ducked down and slipped away, returning to the farmhouse only to find it crawling with German troops. He sneaked back into the field and went east, towards Villers-Bocage.

A little later, while wading through tall grass, smoke shells from the British lines began to land all around, presumably to aid the now captured A Squadron. Dispirited and exhausted, Milner collapsed into a stupor. By when he awoke, it was hours later. The smoke had dissipated. Hungry and thirsty, he waited for night to fall before making his way back towards British lines. After several scares, including narrowly avoiding a party of snoring Germans in a shallow trench and a tumble with an unidentified sentry, he staggered into a 4th CLY cookhouse where he was deftly handed a can of bacon and a mug of tea.

Later summoned to regimental headquarters, he was confronted by the red-faced visage of the CO, Lt-Colonel Victor “Nuf-Nuf” Paley, who demanded to know what the “bloody hell” he had done with A Company. Milner made his report and was released to recuperate. His role in the Villers-Bocage story was over.

Geerman troops inspect the abandoned hulk of the Sherman Firefly”Alla Kafeek.”

British tanks captured on the highway at Point 213. The Germans are busy examining their new prizes.

Captain Roy Dunlop’s Cromwell of the 5th RHA, captured at Point 213.

Germans inspect the Cromwell which was knocked out while probing north of the farmhouse at Point 213.

Back in town, Major Aird ordered Lt. William “Bill” Cotton of the 4th Troop to break through to Cranley, unware that all resistance had collapsed at the Point. Cotton, a popular, seasoned officer who had come up from the ranks and held a Military medal, was skeptical that anything could be done, but he took his troop of four tanks (including one Firefly and one close-support Cromwell) through the town only to stop at a steep railway embankment near the train station. Deciding that it was pointless to carry on without infantry support, they returned to the Maire, the town square with a World War I memorial, to set up a position to ambush any Tigers that returned.

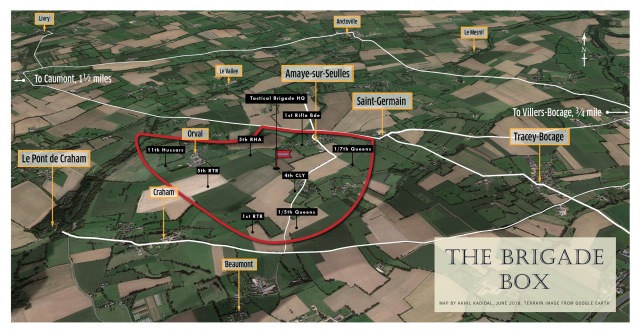

They were soon joined by troops from the 1/7th Battalion, Queen’s Royal Regiment and a single 6-pounder gun which was set up in the alleyway near Cotton’s Troop at point-blank, enfilading position. More Queens filtered into the town at 1 PM. Their commander, Lt-Colonel Desmond Gordon, ordered A Company to secure the train station while B and C Companies took up positions in the center and to the east. They were just in time. When three Germans of a scouting party from the 2nd Panzer Division were captured, they revealed that their division was now entering the fray south of the town. In the matter of hours, the entire tactical situation had changed from a victorious British advance up the road to Caen to that of the 22nd Brigade facing off against two Panzer divisions and a Tiger battalion.

THE AFTERNOON SORTIE

THE AFTERNOON SORTIE

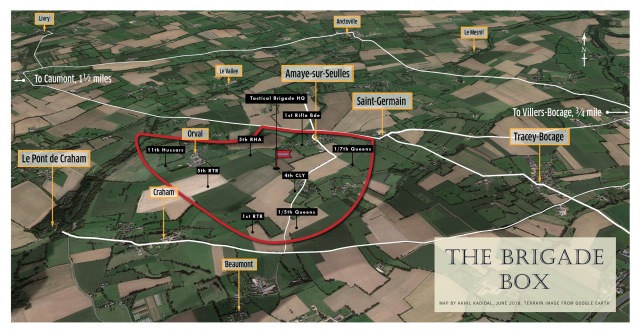

Suspicious of the fate which had befallen the 4th CLY’s A Squadron, Brigadier Hinde now prepared to hold the town with B Squadron and the infantry of the 1/7th Queen’s.

The CLY’s C Squadron was still bivouacked at Tracy-Bocage, a small village 1¼ miles east where it would stay for the remainder of the battle. It was joined there by the Cromwells of the 5th Royal Tank Regiment and a company of the 1st Rifle Brigade. Inexplicable, when Hinde should have retaken the initiative by unleashing this “battlegroup” in a flanking maneuver to cut the enemy’s counterattack at its roots, he did nothing.

Back at Chateau d’Orbois, Wittman had been deliberating with Major Kurt Kauffman, Chief of Operations of the Panzer Lehr, about their next course of action. After warning Lt-General Sepp Deitrich of the I SS Panzer Korps that the 12th SS Panzer Division was blocking reinforcements from moving on to Villers-Bocage, Wittman took a Schwimmwagen back to Villers-Bocage, returning just in time to find Captain Rolf Möbius 1st Company reducing the British pocket at Point 213. Meanwhile, Kauffman ordered Captain Helmut Ritgen of the Panzer Lehr to assemble a force of armor and infantry to go back to Villers-Bocage and plug the northern exit.

Ritgen scraped together a force of fifteen Panzer IVs (mostly from the 6th Company, 2nd Battalion, 130th Regiment) and collected ten more tanks from a workshop south of the N175 highway, before trundling off in the direction of the Maire. En-route they blundered into a screen of 6-pounders. When one of his Panzer IVs burst into flames, Ritgen pulled back. A smaller force of four panzers breached the British perimeter from the south only to pull back after losing half of their number.

Although the tank pincers had been repulsed, German Panzergrenadiers from the 901st Regiment infiltrated the town, resulting in scattered house-to-house fighting. Fearing that he was losing control over his scattered command, Lt-Colonel Gordon of the Queen’s ordered his men to pull back and regroup. His A Company stayed at the train station, but C Company now went to the northeastern edge of the town. D Company occupied the southeastern flank while B Company went into reserve. All around them came the noise of gunfire. To the west, in the direction of what most of the British considered secure territory, the Germans attacked the 1/5th Queen’s Regiment at Livery, losing one panzer.

By noon, Möbius had cleared up Point 213, and now received orders to investigate British activity in the town. All together, he had nine Tigers available for the counter-attack, joined by a dozen Panzer IVs from 2nd Battalion of the 130 Panzer Lehr Regiment. [21]

By noon, Möbius had cleared up Point 213, and now received orders to investigate British activity in the town. All together, he had nine Tigers available for the counter-attack, joined by a dozen Panzer IVs from 2nd Battalion of the 130 Panzer Lehr Regiment. [21]

The raiders went into action at 1 PM, diesel engines roaring as the armada of Tigers and Panzer IV’s rumbled out of their positions and towards the town. Corporal Leo Enderle of the regiment’s 6th Company later recounted: “Before the counterattack started we followed the road along which lay the wrecks of tanks and transport vehicles. When I stuck my head out of the tank I could also see dead bodies.”

A British dispatch rider, seeing the lumbering Tigers and Panzer IVs bearing down the road towards him, braked violently, crashing to the side of the road. Two of the leading Panzer IV’s rumbled over the southern train crossroad and were speeding forward into the town when they were hit by British anti-tank guns and destroyed. Both had been warned not to traverse the crossroads yet, and the second Panzer, though hit, had continued to reverse until a British shell tore through it from the left to the right. The rest of the Germans waited, certain that the crew was dead, but then the loader’s hatch opened and one man emerged, tumbling out head-first, badly bloodied. He stumbled down the field in a daze and collapsed in an adjoining side street where he bled to death. Finally, a few Tigers appeared and blasted the British anti-tank barricade to oblivion.

Möbius’s intention was to seize the town square and he organized the main counterattack down two prongs: the first down the main highway through Villers-Bocage and the second, through the southern section, parallel to the main road.

Certain that this massive fleet of armor would be enough to deter British ambitions, he pushed forward. As they reached the town square, the first prong ran into Lt. Cotton’s ambush. The first Tiger (commanded by SS Lt. Philipsen) was allowed to pass, but the following tanks took the brunt of the ambush. The solitary Firefly, commanded Sgt. “Bobby” Bramall, fired at a passing Tiger, and missed, hitting a building across the street. His second shot tore into the Tiger’s flanks, killing its commander, Sgt. Heinrich Ernst. Ablaze and clanking monstrously, the Tiger came to a halt as its surviving crew spilled out and ran for cover.

Seconds later, Philipsen’s Tiger was hit. It had ranged so far down the Rue Pasteur that it had become an isolated target. Hit multiple times by PIATs and anti-tank shells, the Tiger erupted into flames. The turret cupola clanked open and Philipsen emerged, leaping from his doomed machine to make his escape. A following Mark IV was equally unlucky. Commanded by Sgt-Major Dobrowski of the Panzer Lehr, it was caught off guard by the sudden destruction of its two companions, and amidst showers of PIAT bombs fired by nearby British infantry, attempted to retreat, racing at sped full speed up the main street and firing on houses to keep the infantry down. Unfortunately, Dobrowski had not reckoned on the presence of the Firefly. Bramall deftly pulled his machine out its ambush position at the square, aimed squarely down at the fleeing panzer and fired. The high-velocity shell struck the Panzer IV square in the center, amid a searing shower sparks. A column of flames and smoke erupted from the doomed machine as the German crew scrambled out from flame-blown hatches and attempted to find cover in the ruined street. Cotton ordered them captured, but the Germans escaped in the heat of battle.

By now alerted to the ambush, a group of three Tigers split up. They attempted to flank the British and go south but one came across a Queen’s anti-tank gun that stopped it cold. The battalion commander, Lt-Colonel Gordon later wrote:

A report was received that several Mark VI Tiger tanks were moving down the main street towards the square. Major ‘Tiny’ French of C Company immediately ordered his Company to disperse into the houses in the side streets which overlooked the main road and to be prepared to take aggressive action. He then personally took a PIAT and together with a small party armed with ‘sticky bombs,’ went off further into the town in the direction from which the enemy tanks were approaching. He found four Tiger tanks and one Mark IV in the main street and approached the leading one with from a side street to within 20 yards. He fired two rounds with his PIAT while his party threw their sticky bombs. The results of this attack could not be observed but it caused one tank to move forward where it was driven onto waiting 6-pdr anti-tank guns [of the battalion] and completely destroyed. During this attack one of the enemy tanks blew down a house near which Major French was standing and he was wounded in the leg, but, in spite of this, returned to collect his company and take them into their allotted positions.

On the receiving end, SS Sgt. Werner Wendt of Tiger 132 recounted the heavy fire that his force encountered: “There was fire from all corners. Even today I can still picture Second Lt. Winfried Lukasius as he was knocked out by the close range weapons. He bailed out. His burns looked frightening.” But Lukasius did not die. He rejoined the unit later in the year. In all, the infantrymen of the Queen’s alone accounted for at least two Tigers and a Mark IV with PIATs and Gammon (sticky) bombs. In the end, one last Tiger remained on the main street, waiting patiently for the Cotton’s troop to emerge from cover. Bramall decided to hit it with a shell through a shop window. He fired twice, damaging the Tiger’s gun mantlet. Alarmed, the Germans pulled back slightly and then attempted to race out of town. Determined to stop it, one of the Cromwells commanded by Corporal Horne pulled out of its position and blasted the monster square in the tail, blowing it up. The blazing hulk rolled for another 30 yards before crashing into a building. A cheer of victory went up as an unearthly peace befell the streets. The Germans were retreating.

Möbius later declared that he was forced to withdraw after losing three tanks to close range weapons. In reality, the British had knocked-out six Tigers and two Mark IVs within the town (not counting another four Panzer IVs destroyed on the outskirts). To prevent the enemy from salvaging some of the wrecks, Cotton and Sergeant Bramall went out with petrol and blankets to set the tanks on fire. They almost certainly succeeded in setting three Tigers ablaze, including Philpsen’s machine. For their feats during the battle, Cotton was to get the Military Cross and Bramall, the Military Medal.

As the battle eased at 2.30 PM, Brigadier Ekins of the 131st (Queen’s) Brigade visited Villers-Bocage to see the situation for himself. When Gordon informed him that enemy infantry was infiltrating his forward positions relentlessly, Ekins responded darkly that the situation was hopeless and left. He was not missed. Then at 3.25, Gordon drove to the 22nd Brigade’s forward headquarters at Amaye-sur-Seulles to discuss the battle with Hinde.

There, he found the normally firebrand Hinde, reclusive and ill-prepared to discuss the situation. Gordon stressed that unless his battalion was reinforced, the battle would be lost. Hinde refused to listen. “I don’t think ‘Looney’ quite appreciated that I was rapidly losing control of my companies because of the many tank hunting parties that were dispersed in the nearby houses,” Gordon later wrote. “— A situation not helped by the scarcity of radios in an infantry battalion at that time.” Hinde, however, did radio Major Aird to hold Villers-Bocage at all costs. It was an absurd order.

A Tiger lies destroyed in Villers-Bocage in the wake of the afternoon attack.

This Tiger belonged to Lt. Philipsen.

Sgt-Major. Dobrowski’s destroyed Panzer IV sits aside First Sgt. Ernst’s smashed Tiger.

BITTER FIGHTING TILL THE END

BITTER FIGHTING TILL THE END

Determined to crush all resistance at Villers-Bocage, “Sepp” Dietrich organized a mixed bag of two 88mm self-propelled guns, three field artillery cannons and infantry to infiltrate and recapture the town in bloody street-by-street fighting.[22] Supporting them would be a concerted attempt by the recently-arrived 2nd Panzer Division to circle around and isolate Villers-Bocage from the bulk of the 7th Armored in the west. Soon German units were attacking the British Divisional column snaking back to Amaye-sur-Suelles.

Infuriated by the constant harassing raids along his flanks, the divisional commander, Erskine decided that the time had come to take a more active participation in the battle. At 3 that afternoon, he ordered the 1/5th Queen’s Regiment to advance on Livry in fifteen minutes. This battalion was intended to support the 1/7th Queen’s should the time come. Instead it became embroiled in its own battle against the advancing spearheads of the 2nd Panzer Division.

At 4 PM, in Villers-Bocage, the lead elements of the 1/7th Queens reported enemy infantry approaching again from the southwest. A fierce battle erupted once again. Backed by artillery and mortars, the Germans threw themselves against Queen’s A Company. One platoon was cut off and captured, but the Queens maintained a stoic defense, inflicting severe losses to the enemy and destroying nine panzers. In return, eight officers and 120 men had been killed or wounded. Of greater concern, the Germans had punched several holes in their lines.

In the east, two battalions of panzergrenadiers from the 2nd Panzer Division and several troops of tanks had run into the 1/5th Queen’s at Tracy-Bocage which was being supported by self-propelled 25-pdr Sexton artillery guns of the 5th Royal Horse Artillery. The Germans were so close that the RHA gunners, especially those in CC Battery, began to fire upon the enemy over open sights. Even the other companies of the Rifle Brigade held strong but the attack was so virulent and the British reserves so low that rear area troops were thrust into battle. Cooks, linesmen, signalers and storekeepers were given a weapon and thrust into the fighting. Together, they held back the German tide, killing or maiming hundreds of determined panzergrenadiers and knocking-out eight Panzer IVs.

At Villers-Bocage, two battalions of German grenadiers advanced from the south to hit 4th CLY’s B Squadron. Their blood up, the British tankers routed the Germans, inflicting heavy casualties. On the main street, a solitary Panzer IV appeared out of the smoke and began to shoot up the British positions before it was beset by Queen’s infantry and destroyed. By dusk, the 1/7th Queens were hanging on desperately, their numbers sorely depleted. Gordon radioed that that the town was in danger of falling if reinforcements were not dispatched. But no reinforcements were forthcoming and several British mortars and a carrier were wiped out under scattered artillery firing from both sides. At 4.50, Hinde informed Erskine that the situation had become difficult and that the 22nd Brigade had to be evacuated. Erskine refused.

By 6 PM, with German reinforcements continuing to swirl around the Villers-Bocage, and with 1/7th Queen’s headquarters pinned by artillery, Hinde reluctantly ordered the brigade to withdraw. Due to come under the cover of a smoke screen and an artillery barrage by the 5th Royal Horse Artillery and the American V Corps, the remnants of 4th CLY, the Rifle Brigade and the 1/7th Queen’s prepared to pull out. By now, rumors of a catastrophe had filtered back to the other units of the 7th Armored, promoting a collapse in morale. Most of the men in the rear had no inkling what had really happened in Villers-Bocage. Corporal Peter Roach, a British scout car commander remembered hearing that evening that “the leading regiment…had run into real trouble…Regiment two was sitting dangerously tight while Jerry was making his way down the flanks. Someone was reporting a man moving towards him. Was it a civilian? Perhaps! No it wasn’t. It must be a German infantryman. Suddenly the colonel’s voice, with a touch of weariness and exasperation: ‘Besa the bugger then’.”

The units at Villers-Bocage finally began their withdrawal at 6 PM with the survivors retreating towards a “Brigade Box” at Amaye-sur-Seulles. The last to leave were the tanks of the 4th CLY. The Allied bombardment paused to allow the tanks to escape. At that moment, Sergeant Lockwood’s Firefly stalled.

“I can’t start the bloody thing,” Lockwood’s driver shouted frantically.

With the bombardment scheduled to start the area at any moment, Lockwood considered abandoning the Firefly. To his relief, Sergeant Bill Moore in the leading tank, alighted from his machine and despite the sniping and machine-gun fire, drew a cable link from his tank to the Firefly. They got out just in time. As they departed, Lockwood stared back the town. “We felt bad about getting out,” he said later. “It made it seem as if it had been such a waste.”

The Germans harried some of the retreating British all the way back to Tracey-Bocage and another battle raged there for the next two and a half hours. The attacking German infantry was finally suppressed at 10.30 that night and when they had gone, the troopers of the 22nd Brigade settled in the “Box,” exhausted and angry.

Losses were high for the “Desert Rats,” although there is some confusion on the actual figures. The 22nd Armored Brigade lost 217 men killed, wounded and missing, most of whom had been taken prisoner when the Germans cut off and captured Point 213.[23] The Rifle Brigade lost about 80 men, of which nine had been killed and the rest captured. The 4th CLY lost 85 men, with about four to 12 killed, five wounded and the rest missing or captured. The 1/7th Queen’s had suffered 37 men seriously wounded and seven men killed in combat – a remarkably small number. Two men from the 5th RHA also died.