1941, The Situation Worsens

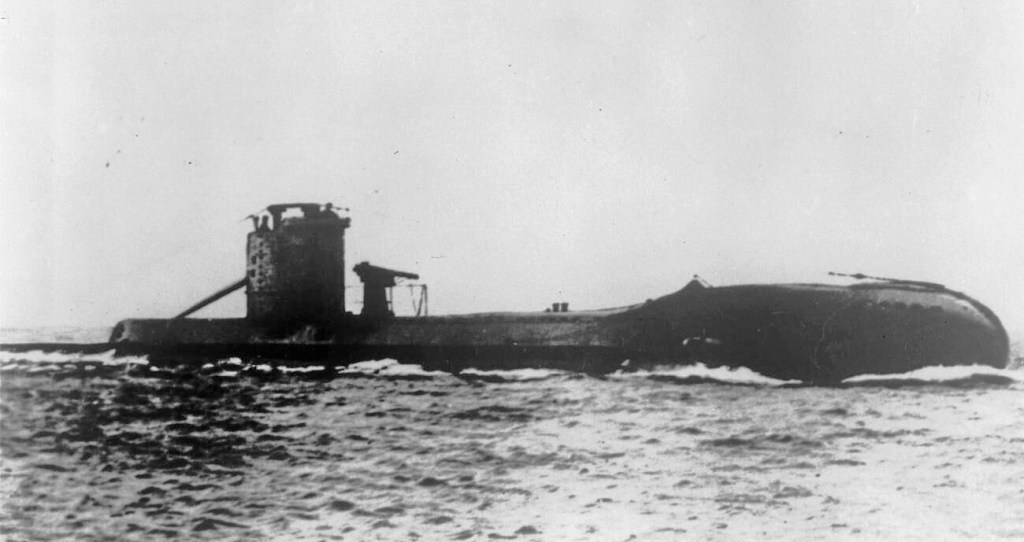

Britain pulled out the bulk of her submarines from the Far East and sent them to Malta where they took up station at Manoel, a small, teardrop-shaped island across the bay from the capital city of Valletta. These submersibles were timeworn O-Class boats, big, noisy vessels, sometimes lovingly finished with teak fittings on the inside, and designed for the rigors of the Pacific. In the shallows of the Mediterranean, they are hopelessly vulnerable and several were lost to enemy action almost at once.

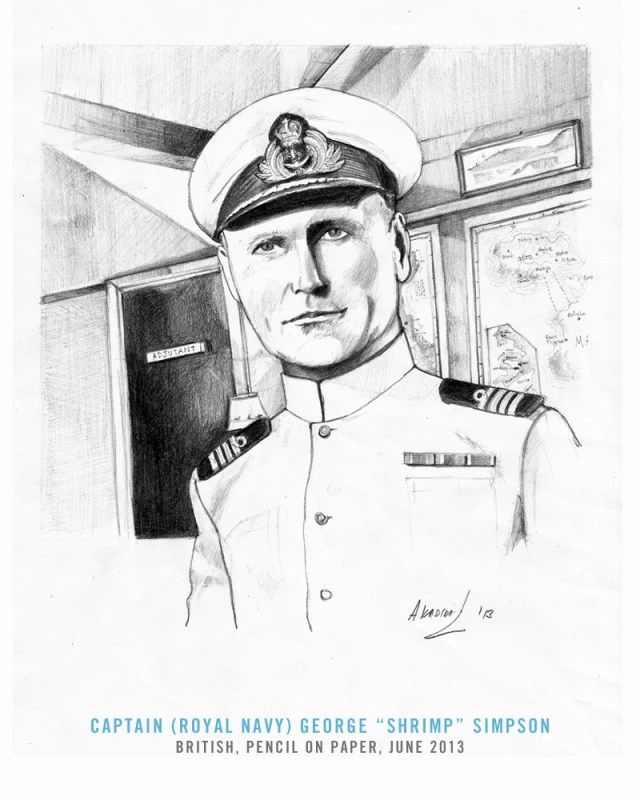

The Admiralty reacted by sending more O-Class boats from the Far East and smaller U-class training submarines from England to join a new flotilla forming on Manoel under Commander George Simpson, nicknamed “Shrimp” because of his diminutive size.

Having been badly bullied throughout his life over his short stature, Simpson had become an empathetic humanist. He was also tough and resourceful and intended to use his fledgling command to sink as many ships carrying Rommel’s command as he can.

London also sent new radar units and more bombers until Malta was a well-stocked fortress prepared to hold its own by the start of 1941. Little did the defenders know, however, that fate was moving inexorably against them.

The first six U-class submarines on Malta, December 1940 to January 1941

| Submarine | Commander | Arrived | Submarine | Commander | Arrived |

| Utmost | Lt. John Eaden* | 8/12/40 | Upright | Lt. Dudley Norman | 17/1/41 |

| Upholder | Lt. David Wanklyn | 14/1/41 | Usk | Lt. Peter Ward | 17/1/41 |

| Unique | Lt. Anthony Collett | 17/1/41 | Ursula | Lt. A.J. Mackenzie | 29/1/41 |

Germany’s Fliegerkorps X, having settled in on Sicily, prepared to do some sinking of its own by the start of the new year. Specialists in anti-shipping, the Germans had taken to practicing bombing attacks on a mock-up of an aircraft carrier off Sicily. The consensus was that four hits were needed to sink a British carrier. Their first victim of the year, they had decided, would be Cunningham’s cherished HMS Illustrious, which was escorting a convoy codenamed Excess to Malta.

Trouble hit Illustrious on 10 January 1941. A mass of German bombers punched through her fighter screen to land six 1,100-lb bombs. Within the space of an hour, Illustrious was on fire and in danger of sinking. Undaunted, her crew affected emergency repairs, allowing her to enter the dangerous Sicilian straits on a straight course towards Malta’s Grand Harbor. More air attacks followed. By when she arrived at Grand Harbor that night, Illustrious was more charred steel and mangled men than a fearsome weapon of war.

An unrelenting Fliegerkorps X followed her to Malta, attacking her repeatedly over the next few days as she lay berthed at the Harbor’s French Creek. A formidable anti-aircraft umbrella thrown up the defenders attempted to stem the attackers. Swathes of bombs pummeled the area all around her, smashing entire neighborhoods in Valletta, Floriana and the densely-populated three cities area across the harbor. Civilian casualties were high. Yet, the resistance of RAF and naval fighters, backed up by the anti-aircraft batteries prevented the Germans from destroying Illustrious.

The Germans re-appeared on 18 January, but inexplicably switched their targets to Malta’s airfields: Luqa and Hal Far. Defending fighters — all of five Hurricanes and four of Illustrious’ Fulmars — rose to the challenge. At Hal Far, bombs plunged into hangers and at least three Swordfishes were destroyed. At Luqa, the airfield’s ack-ack gunners bracketed the sky with star bursts and puffs of black powdery smoke against a large force of enemy bombers.

The Germans flattened two hangers and blasted a Vickers Wellington bomber to oblivion. Shrapnel pierced several other Wellingtons and one bomb fell near the airfield’s wireless building, destroying part of the structure and killed two members of the ground crew cowering in a trench.

The German attacked Illustrious again on the 19th. Two near misses lifted her bodily out of the water and hurled her against the dock wall where she was berthed, perforating the outer hull plating, fracturing her port turbine and flooding a boiler room. Inexplicably, the Germans abandoned all further attacks on Illustrious over the next few days, allowing stopgap repairs to be completed. This allowed the carrier to get away to Egypt on the night of the 23rd. She left her 815 Squadron and twelve Fulmars on Malta to join the RAF defenders.

“German plane after German plane drop like hawks on their prey.”

— Maltese Civilian

Angered, Fliegerkorps X demanded that Berlin send fighters to eradicate the RAF on Malta. The Luftwaffe high command obliged by sending a squadron of budding aces and killers.

As members of the island’s sole fighter unit, the pilots of 261 Squadron had lived a comfortable, unhurried existence. Facilities were not be on par with England, but morale was high, casualties were low and reinforcements frequent. That changed when the squadron of Germans, equipped with Messerschmitt Me109E fighter aircraft commanded by a driven, young ace, Oberleutnant (First Lt.) Joachim Münchberg, began operating over the island.

Müncheberg was a 22-year-old farmer’s son from Pomerania and the embodiment of “German purity.” A born athlete who had forsaken athletics for the ultimate sport — air combat, he had joined the Luftwaffe in November 1938. His first kill was a British Blenheim Mark I light bomber, brought down over France on 7 November 1939. Other victories followed, including four in a single day in May 1940. In 1941, Müncheberg brimmed with confidence, although much later he would become badly disillusioned by the war and lose his way. In 1941, he was a media darling. His men adored him and looked to him to show the way. He did not disappoint.

The Me109s immediately established air superiority over the island. British casualties began to skyrocket and as March turned to April, 261 Squadron was fighting for its life. To add insult to injury, the Allied pilots found themselves being treated with condescension by “Sammy” Maynard and the new governor of Malta, General William Dobbie. The governor, a devout member of the Plymouth Brethren faith, would later be accused of praising the lord but not passing the ammunition.

Claims filed by pilots for enemy aircraft shot down were repeatedly turned down by headquarters which was unequivocal in its opinion that the pilots are not doing enough to stop German raiders.

“We begin to feel that we have to lob the bastards into Dobbie’s or Maynard’s front garden before we can get a confirmation,” complained an Australian pilot officer, John Pain. Many RAF pilots found that it was futile to point out that their aging Hurricanes were no match for Messerschmitts.

Malta was reeling by mid-March, wracked by military losses, an escalating civilian death-toll and the beginning of serious economic hardships. Münchberg’s squadron, having achieved total air dominance, roved across the island at will, terrorizing the RAF and civilians alike. “The island is down to eight serviceable Hurricanes,” Cunningham wrote London. “I am seriously concerned…”

RAF on Malta, April 1941

| Unit | Aircraft | No. | Unit | Aircraft | No. |

| 261 Squadron | Hurricane I | 12 | 69 Squadron | Maryland | 4 |

| 228 Squadron | Sunderland | 5 | 830 Sqdn, FAA | Swordfish | 10 |

The arrival of a British convoy of four freighters with 45,000 tons of goods solved the immediate problem of supplies, but this did little to address the rampant damage being caused by Fliegerkorps X. When Simpson’s submarines retaliated by sinking several Italian freighters moving troops and supplies to Libya, Rommel demanded that the Italian navy protect convoy routes. The fleet obliged but met the Royal Navy.

A fierce battle erupted, resulting in the destruction of five Italian warships and the deaths of 2,400 Italian sailors for the loss of a single British aircraft. Cunningham was jubilant. At Hitler’s headquarters, the reaction was one of fury.

Despite being resupplied in March, Malta’s food stockpiles continued to dwindle at an alarming rate, prompting the authorities to introduce the rationing of certain food items, including coffee and sugar. The Maltese worried that the island staple, bread, would follow. Fliegerkorps X continued to pummel the island. From mid-January to the end of May, it hit Malta with 459 raids, an average of 92 a month, prompting Göbbels to write: “Malta heavily-bombed. There can be nothing left there.”

But the British had no intention of quitting just yet. Dobbie requested more troops, warning that the island could be invaded at any time. In April, the Wehrmacht High Command informed other branches of the service that Hitler intended to conquer Malta in the autumn of 1941. When pressed on the matter, Hitler expressed concern that any potential invasion of the island was doomed to failure because of the questionable fighting prowess of the Italians whose military support was critical. Rommel was unswayed.

“Without Malta, the Axis will lose control of North Africa,” he said and cited the loss of thousands of tons of cargo since the start of the year to British submarines operating out of Malta and Alexandria as evidence.

But it was no cakewalk for the British submariners. Lt. David Malcolm Wanklyn, tally and gangly, with large, sharp eyes softened by amicability and a narrow, contoured face highlighted by a prominent aquiline nose, was supposed to be gifted submarine commander. But his operational performance had been mediocre.

Part of Wanklyn’s problem in 1941 was a shortage of torpedoes (or “Tinfish” as the submariners called them) — not just at Malta, but in the Royal Navy on a whole. In 1940, just 939 torpedoes were available to the submarine service when it actually required at least 1,200.

At Malta, many submariners had to make do with older and unreliable stocks of tinfish, many of which are known to veer off course or explode prematurely. In January, at least one submarine, HMS Truant, became exposed to enemy fire after one of its torpedoes exploded prematurely and destabilized the submarine. The vessel survived this brush with death and returned to Malta, its crew shaken.

To economize minimalist stocks on Malta, submariners are under orders to fire just one torpedo against easy targets, when sometimes a full spread was required. The standard U-class submarine could carry eight 12-inch Mark VIII torpedoes, but until July 1941, few submarines going out on patrol had the luxury of a full complement.

Even as Simpson publically attempted to defend Wanklyn from charges of incompetency, Wanklyn redeemed himself on 25 April by sinking the 5,428-ton Italian freighter Antonietta Laura — a feat followed a day later by his crew’s boarding of the grounded German freighter, the 2,452-ton Arta, a survivor of the so-called “Tarigo Convoy,” off Kerkennah.

Surfacing in brilliant moonlight and creeping forward in the shallows of the bank, the wet sandbars gleaming in the light, Upholder inched onward until her crew could see Arta’s decks crammed with motor transport. The ship appeared to be deserted and Wanklyn authorized a boarding party. At 8.20 PM, the boarding party, under Lt. Christopher Read, armed with Thompson submachine guns, clambered aboard the German vessel.

The ship was indeed deserted, save for the dead.

“There are a few ‘good’ German soldiers [aboard] and a good stink was coming from them,” said one of boarders.

Pushing on into the bowels of the ship, the boarders blew open the captain’s safe and secured key documents. Then, capturing as much Germany army equipment as possible — flags, submachine guns, helmets, boots — they placed demolition charges on the stricken ship and escaped. At 9.44 PM, explosions shattered Arta’s dual holds and set the ship ablaze, casting a lurid light on the sandbars and frightening seagulls which stared baffled.

Further successes came on May 1 when Wanklyn attacked a German convoy, firing four torpedoes in a spread at 11.32 AM which hit the German ships Arcturus and the Leverkusen. The latter was carrying the divisional headquarters of a panzer division.

At 11.44 AM, submerged to wait out the inevitable Axis depth-charging, the British heard three distant explosions. When Upholder climbed back up to periscope depth an hour later, the submariners saw the Arcturus sinking while Leverkusen listed heavily. Wanklyn was reluctant to use another torpedo against Leverkusen but at 2.45 PM, the ship was seen on an even keel and working up speed to get away. Alarmed, Wanklyn came into position and fired his last two torpedoes at 7.01 PM. These tore into Leverkusen. She san 44 minutes later.

Flush with success and out of torpedoes, Upholder returned to Malta. As they entered Lazaretto Creek on May 3, the crew mustered up on deck, grinning broadly, “with a guard of honor on the far casing wearing German helmets, carrying German tommy guns and flying the German ensign.” Wanklyn had vindicated himself and his crew.

In all, Malta-based submarines sank nine Axis merchant ships and an irreplaceable cruise liner between late February and late May 1941. Gratified by such mastery at sea, Churchill ordered a military convoy to sail directly from Gibraltar to Egypt. The supplies were intended to stabilize Britain’s crumbling North African front. Rommel had launched an offensive which had seen German and Italian troops sweep towards the important coastal city of Tobruk in Libya’s Cyrenaica province.

The British naval chiefs protested. Axis air domination had made direct sailings to Egypt a thorny proposition and most British convoys destined for Egypt took the long route — around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. Churchill, however, was adamant. Naval escort aircraft were deployed on Malta to cover the convoy. But this only served to heighten German attacks on the island.

Valletta was pounded relentlessly, prompting at least one Maltese to tell Dobbie: “We will endure anything except the rule of these barbarians and savages.”

Meanwhile, the British convoy, codenamed “Tiger,” was also attacked. Malta-based warships intended to protect the convoy were unable to move out of Grand Harbor because of Axis mines in the water, and a valuable Allied freighter was destroyed. The British would never mount a direct convoy to Egypt again until 1943.

The morale of the RAF unraveled with each successive German attack. Maynard split 261 Squadron and merged the balance with reinforcements to form a new fighter unit, No 185 Squadron. But losses in aircraft and pilots continued on an unsustainable scale. In desperation, London decided to send three fighter squadrons to help Malta.

All three units (Nos 213, 229 and 249 Squadrons) were veterans of the Battle of Britain. The squadrons also had to provide a degree of air support for the British army in North Africa, now struggling to contain Rommel’s Afrika Korps. The Axis had cut-off Tobruk and were laying the ground for a lengthy siege of the port city. Meanwhile, Rommel’s forward elements had pushed on towards the Egyptian frontier.

Of the new units, 249 Squadron was the most illustrious British fighter unit of the Battle of Britain. It had none of the self-righteous arrogance or the pedigree of the other squadrons of Fighter Command but its men, mostly hailing from the much-maligned proletariat backgrounds, had shot down more Germans than any other British squadron in the Royal Air Force.

“The thing that impressed us was the complete absence of bullshit by the regulars.”

—Pilot Officer John Beazley, 249 Squadron

They are also men who had become increasingly weary of the eventless patrols that dominated RAF Fighter Command operations in Great Britain, since the winter of 1940. Anxious for more action, several pilots, including a mercurial young Lancastrian named Tom Neil had asked for a transfer overseas. Senior officers, however, had decided to transfer the entire squadron abroad. So the men went, expecting exotic locations, perhaps even India. Instead, they are dismayed to find themselves on Malta. Most saw the island as a dismal place full of swirling ochre-colored sand, bad food, intolerable heat, chaste women, dubious aircraft, and where the Germans held every advantage.

Neil and his squadron struggled to come to terms with Malta. Everything about the island repulsed Neil — their dusty airfield at Takali, the island’s battered and badly patched up Hurricanes, the lack of proper housing, the armies of fleas found in every bed and room, the general filth of the place, the inefficiency of operational procedures and the island’s utter primitiveness when compared to England.

Within days of their arrival, the squadron was caught by Münchberg’s Messerschmitts on the ground and given a pounding. Their high morale, carefully fostered in the skies over England, evaporated. But a reprieve was at hand. The Messerschmitts returned to France six days later, having wiped out 48 British aircraft on Malta without suffering a single casualty. Had they stayed on in Sicily, they could have wiped out the RAF within a few short weeks. But this was not the only mistake that the Germans made.

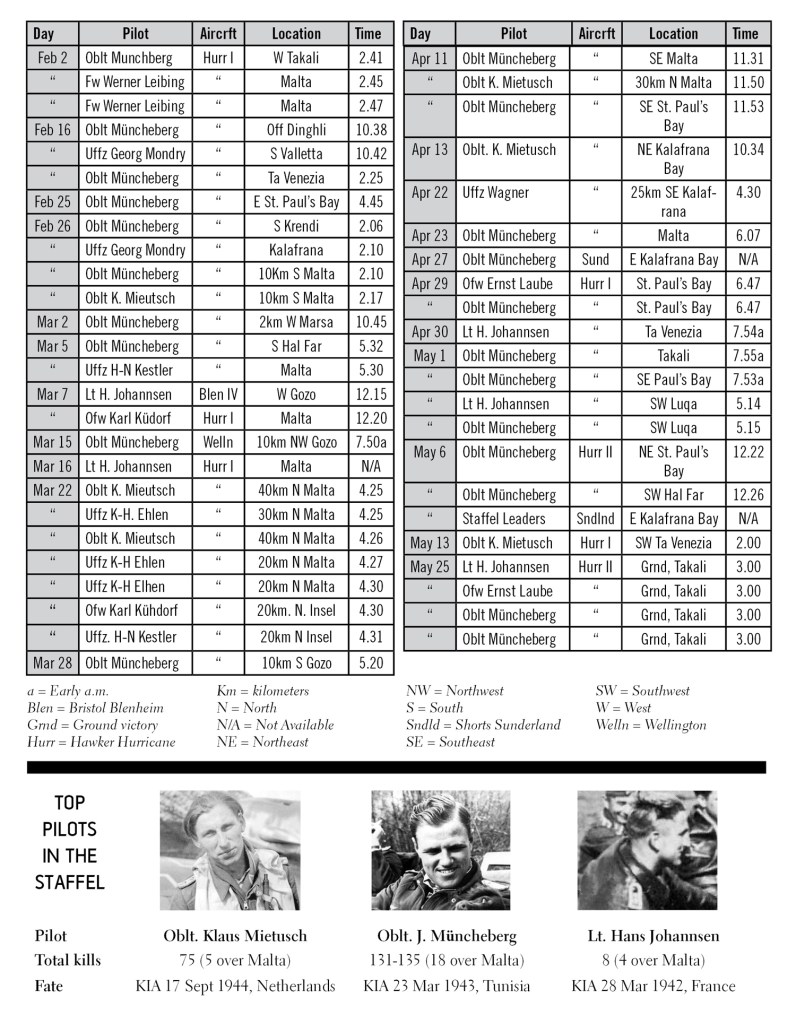

The kill tally of 7/JG26

Fliegerkorps X had also been reinforced with squadrons of Heinkel He111 bombers and a new fighter group, III/JG27, led by the 23-year-old Oberleutnant Erbo Graf von Kageneck, a pleasant-faced, blonde-haired pilot whose aristocratic origins rendered him an invaluable propaganda tool for Göbbels.

The von Kagenecks were heavily invested in the war (one brother was a celebrated tank commander) and Kageneck himself was an ace — albeit a minor one, for his tally of 13 victories did not yet permit him entry into the elite club of the experten — those pilots who had scored at least 15 victories in the air. Those aces who had scored 40 kills were rewarded with the coveted Knights’ Cross, the WWII-generation’s “Blue Max.” Despite participating in the invasions of Poland, Belgium, France and Greece, and fighting over Britain in the summer of 1940, von Kageneck had scant opportunities for combat. Malta, he hoped, would end his lean streak.

Jagdgeschwader 27 was equipped with Me109 E-7s, their engine cowls painted a bold yellow over which appeared the jagdgeschwader’s strange and unmistakably racist badge of a stylized leopard head overshadowing a horrified African wearing loopy earrings. The pilots were a professional bunch but had been marginalized by the other wings during the Battle of Britain because of their abysmal performance. In that battle, they had lost 83 Me109s in combat and had suffered 58 pilots killed, captured or missing by December 1940. In return, they had claimed 146 RAF aircraft shot down — but this figure was likely incorrect as overclaiming was endemic within the Luftwaffe. The arrogance of the German pilots was quantifiable, their aspirations for greatness absolute.

Malta’s radar warned of an incoming raid just before midday on May 6. ‘C’ Flight of 261 Squadron scrambled only to realize that it was badly outnumbered by 30 to 40 Messerschmitts from III/JG27 and Münchberg’s 7th Staffel escorting four Heinkel He111 bombers. A fiasco ensued. Four Hurricanes were shot down but miraculously, only one pilot was a casualty — Pilot Officer Dredge, who suffered injuries and burns while trying to crash-land. He was Kageneck’s 14th victory of the war.

At the end of May, instead of using his paratroopers to invade Malta, Hitler attacked Crete in the eastern Mediterranean — a decision of such misplaced ambitions that history would remember it as a monumental error. Until late in 1942, Hitler failed to understand that the Mediterranean was one of the most important theaters of war in which the British Empire could be fought and defeated. He could not see that the prestige of the British Empire was “inseparably linked with Britain’s influence in the Mediterranean,” or that the region presented the British Army with the means of occupying itself after its unceremonious exit from France in 1940.

Without the North African battlefields, the British Army would have grown fat and indolent while waiting in England for the cross-channel invasion of France.

Hitler’s intentions for Crete did not have as much to do with obtaining a strategic advantage in the Mediterranean as they did with buttressing his southern flank. This was intended to prevent the British from using Crete to bomb oilfields in Romanian. Crete fell on the first day of June, but not before 2,000 German parachutists were killed and another 4,000 were wounded. German commanders expected to follow up the victory with an airborne invasion of Malta. To their shock, Hitler, who was appalled by the losses and convinced that paratroopers could never be employed with the element of surprise against Malta, declared that “the day of the parachutist is over.”

By the end of May 1941, two thousand Maltese homes had been hit by bombs. Three hundred Maltese had died so far, with another 250 seriously wounded and 12,000 rendered homeless. Unhappy with Maynard’s inability to attain air superiority, Dobbie sent a letter to London asking that “tired and jaded” officers be replaced.

Churchill, who read all Malta-origin dispatches religiously, concluded that Maynard was out of his depth in the sort of heavy fighting now emerging at Malta. All eyes now fell on a veteran bomber-man, Air Vice-Marshal Hugh Pugh Lloyd, to replace him. Lloyd was a bombastic veteran of World War I – and not above petty theatrics.

Nothing deterred Lloyd, 46-years-old whose genesis was noteworthy. He had joined the army in 1914, at the onset of that war. He had served as a dispatch rider, then as a sapper and finally as a pilot for the Royal Flying Corps (RFC).

As a combat engineer he was wounded thrice before deciding that the ground was not the best place for him. He subsequently transferred to the RFC in 1917 and was posted to No 52 Squadron, a bomber unit operating over the trenches of France. His heroism was unquestionable. He had won the Military Cross and the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for combat heroics but his penchant for invention and exaggeration was legion. He once told a Wellington pilot on Malta that he had served as a child soldier during the war, enlisting at the age of 14. In fact, he was 20. His displays of the stiff-upper lip and stoicism were mistaken for fortitude and his later play-acting of courage under fire while clamping down a cigarette holder in his mouth to metaphorically represent the “bit” between his teeth, was often confused for grit. Lloyd was also a confirmed bomber-man with little regard for fighter tactics, although no one realized this at first.

Lloyd’s orders were to focus on sinking “Axis shipping sailing from Europe to Africa.” It was an order that he would take to heart — at the cost of nearly everything else.

Lloyd’s arrival in the first week of June was followed by a profoundly depressing tour of the island squadrons and military bases. Except for the headquarters of the military which was set in a cavern under Valletta, critical facilities are all above-ground and vulnerable to bombing. The airfields were in poor shape and too small to support large-scale operations. Equipment such as tractors, steamrollers and bulldozers needed for expansion work were non-existent and a shortage of motor transport forced Maltese laborers to depend on horse-drawn carts.

The island had trace amounts of bitumen and tar, but its steam rollers were meant for civil road construction and were too light for airfield application. There was just one steam roller “equivalent in weight to a Blenheim.” When lightweight steam rollers were used, Lloyd discovered that heavy aircraft left standing on tarred ground for a week had a tendency to partly sink, preventing them from getting out on their own power.

At Takali airfield, where the landscape was reasonably flat, work progressed at brisk pace. Aircraft pens, each with a small room for equipment and offices, were drilled into the side of the Mdina Hill, at the edge of the airfield. Other bluff faces around the airfield were similarly tunneled to get equipment underground, including motor vehicles and aircraft repair machinery. At Hal Far and Luqa airfields, the work was tortuous. Efforts to connect the three airfields using aircraft tracks faltered because of the sheer ribald toughness of the country. In the end, only Luqa was connected with Hal Far.

The sun scorched in June, the final month of the Maltese spring, to be followed by the harsh summer when temperatures rose to an average of 92° F. Slaving away in the blistering heat, the Maltese police, civilians and British sailors completed the taxi track to Safi in a single day and inaugurated it that evening to great fanfare. The Army watched silently on the sidelines, patrolling isolated beaches and watching the coastline, its numbers too insubstantial to thwart an invasion but covetous enough for government officials seeking an untapped source of labor.

In early 1941, the army numbered 10,000 troops, boosted by the arrival of a battalion each of Hampshires and Cheshires from Egypt. These battalions joined the 2nd Devons who had been on the island since 1939. Conscription was passed on February 19, making all men aged between 18 and 41 eligible for military service, exempting those Maltese employed in government, at the docks, as stonemasons or as stone cutters. This added a further 14,600 Maltese conscripts to the army, and by August 1941, the army would boast of having 22,000 men in uniform. Its tepid patrol duties, however, prompt derision. The RAF never passed up an opportunity to mock the “pongos” for their “passive” war.

The army mitigated some of this heckling by offering to help expand the taxi track from Luqa to Hal Far, going so far as to build a bridge over a nullah. Bands of laborers also built a roundabout track which was nicknamed “Stirling Valley” under the delusion that the Shorts Stirling was the best British bomber in the RAF. The so-called “Stirling” loopway became a critical addition to Luqa, allowing aircraft to collect in a ground circuit. Surveyors also identified a cavern in a ravine at the end of Luqa’s main runway where valuable aircraft and engine repair shops could be moved. However, work moved at a snail’s pace.

Nevertheless, with reinforcements at hand, and with British submarines brining in small quantities of supplies from Gibraltar, Lloyd set about executing his “brief to attack.”

Meanwhile, decryptions of German intelligence signals by Bletchley Park, the nerve-center of British codebreaking operations, had revealed that the Italians were sailing a series of convoys to North Africa in mid-July 1941. Malta’s submarines were vectored into the area. Several Axis transport were sunk — giving Rommel added reason to complain that the Italians are not doing enough to protect the convoys.

British Submarine Kills, Mediterranean, February to May 1941

| Submarine | Date | Ship destroyed | Tonnage | Location | Notes |

| Upright | Feb 25 | Armando Diaz | 7,080 | off Sfax | 464 crew killed |

| Utmost | Mar 9 | Capo Vita | 5,683 | Gulf of Hammanet | Blew up |

| Unique | Mar 10 | Fenecia | 2,584 | Off Tunisia | |

| Utmost | Mar 28 | Heraklea | 2,500 | Off Kerkennah | Carrying troops |

| Rover | March | Cosco | 6,000 | Off Calabria | |

| Tetrach | Apr 12 | Persiano | 2,474 | Off Tripoli | Tanker |

| Upholder | Apr 25 | Antonietta Laura | 5,428 | Lampedusa Channel | |

| Upholder Upholder | May 1 | Arcturus Leverkusen | 2,576 7,382 | Off Kerkennah | |

| Glavkos* | July | Several boats | N/A | Off Rhodes | |

| Urge | May 20 | Zeffiro | 5,000 | Off Tunisia | |

| Upholder | May 24 | Conte Rosso | 18,000 | Off Sicily |

For Rommel, every cargo ship sunk was one less unit of supply which prevented him from advancing into Egypt. In a letter to Hitler on July 19, he wrote that: “It is my feeling that the Malta problem must be solved immediately.”

Hitler stalled for time. But Dobbie’s prognostications that Malta would go the way of Crete if it was not resupplied, prompted the British put together a convoy of six freighters to restock the island. Codenamed Substance, the convoy braved heavy attacks by Italian aircraft and torpedo boats. It landed 65,000 tons of supplies on Malta. This gave the island an eight-month supply of arms and ammunition, and 7½-months of food and civilian commodities.

Humiliated by their inability to stop the convoy from arriving at Malta, the Italians sent midget submarines and small explosive boats to penetrate the defenses of Grand Harbor and sink the freighters at their moorings.

Engine noises out at sea, coupled with radar imagery, betrayed the Italian assault force gathering off the Maltese coast in the darkened hours of 25/26 July. When the Italians proceeded with their attack, disaster ensued. Fixed by powerful searchlights and pounded relentlessly by coastal guns, the initial wave of fast attack boats were wiped out at the entrance to Grand Harbor. At dawn, RAF Hurricanes took off to hunt down the rest. They caught up with the Italians as they were midway to Sicily. Only 11 Italians survived out of the original force of 44.

1941. An Island in Angst

Just when the travails of the Maltese reached a pitch, Fliegerkorps X was transferred to Crete. This gave the islanders breathing room. Lloyd occupied himself with wrangling aircraft and men for his command. Aircraft transiting to Egypt via Malta were “hijacked” and their crews pressganged into local squadrons. Yet, Lloyd was strangely ignorant about the needs of his fighter units. When Tom Neil and several others ask him for better aircraft, preferably Supermarine Spitfires (the premier British fighter aircraft of the war) he lambasted them for not being “more offensive-minded.”

Oblivious that he was earning the scorn of his fighter pilots who had started to refer to him derisively as “Hughie-Pughie,” Lloyd concentrated on honing Malta’s offensive power. He likened his attack units to the “Sword of Achilles,” a statue in Hyde Park which had struck his fancy. He feted his bomber and multi-engined aircraft crews, going out of his way to praise the unconventional, puerile reconnaissance pilot, Flying Officer Adrian Warburton, for actions he believes were beyond the call of duty. In comparison, all he could see among his fighter pilots were grousers and malcontents.

Malta’s submarines were hammering enemy shipping, but they are also being bled white in the process. Morale, however, remained high and Simpson received permission on September 1 to christen his command the 10th Flotilla.

Alarmed, Vice-Admiral Eberhard Weichold, the German naval liaison officer at Italian Supreme Headquarters (Comando Supremo), reported to Berlin that the British submarine were “the most dangerous weapon” in the Mediterranean. This statement was borne home when Luftwaffe (German Air Force) units in Africa reported that they running out of supplies because of losses at sea.

The German Naval War Staff recommended the immediate return of German air units to Sicily. Hitler responded by ordering Fliegerkorps X to protect Axis convoys from their new bases in Crete and by ordering 20 U-boats into the Mediterranean, despite arguments from his naval chiefs that “British aircraft and submarines…in the Mediterranean…cannot be combatted by U-boats.”

Far from the Mediterranean, meantime, Sergeant George Beurling, a 19-year-old Canadian in the Royal Air Force whose name was destined to become irrevocably linked with Malta, visited London to celebrate his graduation from preliminary flight training.

His convoluted journey into the RAF was the culmination of a 11-year fascination with flight which had seen him hang around local airfields in Canada as a young boy. He had subsequently obtained a private pilot’s license at the age of 17. Then followed his misbegotten attempts to join various air forces around the world after he was turned down by his native Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) because of his lack of a high school diploma. Flying for Canada, the blonde-haired Beurling later said, was “reserved for university graduates, or people with brown hair or former glass blowers, but certainly…not young men who wanted to get in there and fight.” And Beurling badly wanted to fight.

His attempts to join the Chinese Air Force came to naught when he crossed illegally into the United States to catch a boat from San Francisco. Outed by a policeman, he was arrested and deported. In the end, only the hard-pressed RAF, anxious to replace its losses of the Battle of Britain, would have him.

Beurling preferred to think of a war as an adventure. In London, however, he was confronted by its brutality. On one occasion, during a German bombing raid, he witnessed a little girl playing with a doll in the middle of a street. As he rushed to carry her to safety, he noticed that one of her arms had been severed at the shoulder. On another occasion, he was confronted by the sight of a woman pinned in the underground by bomb debris. As the tunnel filled with water, a doctor was brought in to amputate a leg in order to free her. Beurling was sickened. “For the first time, I was just plain, redheaded mad with the whole German race,” he said.

As the lull continued, Malta once again became a staging post. Entire flights of aircraft passed through the island, destined for North Africa. In mid-September, however, 23 Hurricanes arrived for Malta’s squadrons, having been launched from a British carrier.

Realizing that the island was regaining its strength, the Italians launched a series of air attacks. But whereas the Germans were mounting two to three large raids every day, the Italians were able to execute only two to three heavy raids every week — and losses were heavy. The raiders faced a phalanx of anti-aircraft guns, fighters and during the hours of darkness, radar-equipped nightfighters.

By mid-September, the Tenth Flotilla was also itching for fight. An opportunity came on 17 September, when British Intelligence revealed that a large Axis convoy with three ocean liners had sailed from Taranto with troops and ammunition for Rommel.

Simpson was at his office in Lazaretto when Lt-Commander Bob Tanner burst in with the “hot” news. Simpson realized he had 90 minutes to scramble his submarines if he had any hope of catching the convoy. Whatever else the virtues of the U-class British submarines might have been, speed was not one of them. They could manage a measly 11¼ knots on the surface and 10 knots submerged. Simpson summoned his boat captains — Lieutenants David Wanklyn, Teddy Woodward, Arthur “Baldy” Hezlet, Johnny Wraith and Edward “Tommo” Tomkinson, and proposed sending Upholder, Unbeaten and Upright to set up a ambush sixty miles northwest of Homs. The two remaining submarines, Urge and Ursula, were to be positioned off Homs to catch any that Axis ships that broke through.

Simpson was aware that some of his submariners had recently returned to port and were not fully rested. He asked for volunteers. Tomkinson stepped forward and said: “Quite frankly, sir, I don’t care about these sudden schemes devised on a signal just received. I would ask you to count me out.” It said much for Simpson’s style of command that he replied: “All right, Tommo, then Urge won’t go and Arthur Hezlet can take long stop at Homs alone in Ursula.”

Four British submarines slipped into the Mediterranean. Lt Woodward’s Unbeaten moved towards Cape Bon, while Wanklyn’s Upholder and Wraith’s Upright patrolled the coast towards Tripoli. Hezlet’s Ursula waited at the entrance of the swept channel ahead of Tripoli where he intended to sink any survivors within sight of safety.

The convoy, consisting of five destroyers and the Italian liners, Oceania, Neptunia (both with displacements of 19,500 tons each) and Vulcania, had left Italy late on September 16. They were due to dock in Tripoli at 9 AM on the 18th.

The liners were veterans of previous convoy runs as were their escorts. They were prepared for trouble —or so they believed. The first British submarine to spot the convoy was Woodward’s Unbeaten, at 3.07 AM on the 18th. Unfortunately, the ships were eight miles away and Woodward watched helplessly as they steamed by. Woodward ordered a slow pursuit even as his crew attempted to warn the other submarines of the approaching ships. The wireless transmission failed but the communications officer managed to get the word out using the submarine’s asdic system.

Wanklyn received the signal at 3.40 AM. He spotted the convoy six miles away. Surfacing, he made for the convoy at top speed. With her gyrocompass out and yawing badly in rough seas, Upholder strained to reach attack range. Twenty-eight minutes later, Wanklyn saw two liners overlapping in the distance. He fired a salvo of torpedoes. As the tinfish raced towards their targets, Wanklyn waited calmly, reconstructing the attack in his mind, retracing his actions. In any case, it was out of his hands. Either the torpedoes would hit or they would miss.

Just when it seemed that the salvo had missed, one of the torpedoes slammed into Oceania’s aft with a thunderous bang, cutting off her propellers and crippling the ship. A second torpedo tore into Neptunia, which appeared to rise out of the water. A moment later, she plunged back into the water stern first, like some great whale falling back into the sea in an awful screech of breaking metal and deforming bulkheads. Woodward who was closing in from the north, had his breath taken away. “My God,” he said, watching through his periscope. “Everything was lit up, searchlights everywhere.”

As the escorting destroyers frantically try to shield Oceania, Vulcania tried to make a break for it, speeding from 17 knots to her maximum of 21. Wanklyn dove and closed in to deliver a coup de grace on the Oceania. The great liner loomed large as the thin line of dawn broke. She was painted in an outrageous, sunburst camouflage scheme of blue and ocean grey. A destroyer loomed out of morning gloom and and sent Wanklyn deeper. When the destroyer had passed, Wanklyn and Upholder rose back up and fired two torpedoes at the liner.

Woodward had foolishly come in between Wanklyn and Oceania, intending to make his own attack on the liner when his asdic operator reported a torpedo in the water coming straight at them. He immediately flooded his Q ballast tank, plunging the submarine to 90 feet just as the torpedo screamed by overhead. Moments later, the shattering boom of an explosion reverberated in the water. The strange sound of an ethereal net being dragging over their submarine accompanied by lots of little pops and bursts engulfed the submarine. It was the sound of the Oceania in her death throes.

Wraith’s Upright attempted to nail Vulcania, but missed and this liner reached Tripoli intact. The so-called “Battle of the Bottoms Up” was over.

At the time of her sinking, Neptunia was carrying 312 crewmembers, 1,799 Italian troops and 827 Germans and Oceania was carrying 314 crew, 1,767 Italian troops and 819 Germans to give a total of 5,838 people. While Simpson estimated that some 5,000 had been killed, actual figures were likely 383 people — the majority of whom had perished during the explosive impact of the torpedo upon the Neptunia.

A disproportionate number of those who died in the water were German troops who had insisted on going overboard with their full kit and rifles. Simpson conceded that over 5,000 were rescued from the sea by the escorting destroyers which should have themselves been sunk had the flotilla been equipped with modern torpedoes (they had pre-war Mark IVs).

“I thought about this for a long time,” Simpson said. “…To be merciful is something we were in no position to afford.”

In Rome, Supermarina bemoaned the loss of the “magnificent ships,” with naval officers cursing the circumstances which had forced their employment. Count Ciano wrote in his diary on September 25 that: “The Mediterranean situation is dark and will become even more so…in responsible naval quarters they are seriously beginning to wonder whether we shouldn’t give up Libya willingly, rather than wait until we are forced to do so by the total lack of shipping.”

In stark contrast, the British were ecstatic. Wanklyn was the hero of the hour. Back at Lazaretto, Wanklyn’s crew acquired a new flag in honor of their victory — black with a skull and crossbones — the famed “Jolly Roger.”

The flag was the revival of an ancient naval tradition frowned upon by senior naval officers. Its reappearance had precedence in September 1940, when the submarine Osiris, having been posted in the “seemingly impenetrable” Adriatic, had claimed the sinking of a destroyer (in fact, it had sunk the 897-ton Italian torpedo boat Palestro). With the excitement of this first sinking, Malta-based naval officers had intended for their submarines to fly the pirate flag at the conclusion of every successful war patrol.

For Simpson, the act of flying the flag gave him an opportunity to heighten the esprit d’corps of his flotilla and link their activities to the age of Malta’s Knights of St. John and the corsairs once under their employ. He was aided by Carmela Cassar, a Maltese woman of about 60, distinguished, tall and ageless, who arranged to have a series of silk and lacework flags made by Maltese nurses and the nuns of a local convent.

One flag is presented to each submarine commander. The Upholder’s crew stitched two white chevrons on their four-by-four-foot flag to indicate two supply ships sunk. A system of marking develops — White stars to indicate ships sunk by gunfire, daggers to indicate a successful commando raid launched by submarine and red chevrons or bars to indicate a warship sunk by torpedoes.

Yet, Wanklyn himself was “morose and disgusted.” He told all those who asked about his dejection that only sheer luck had allowed him sink those two ships. He had used no proper calculations, no readings, nothing but the naked eye peering through the periscope — and firing his “tinfish” when he saw two ships overlap each other. This gloom partly affected his psyche. The next six weeks, from September 23, were like being limbo. Wankyln and the Upholder did not sink any ships for the simple reason that they never saw any ships.

His gloom was not reflected in the Admiralty, for having witnessed the disruption of the Axis convoy routes, the sea lords planned their own massive nine-ship convoy to the island — the largest number ever sent to Malta in one go. The convoy was codenamed Halberd.

When an Italian seaplane spotted Halberd sailing east towards Malta with a massive escort of warships on September 26, the Italians mobilized for battle. They had decided in May that they would expend their remaining oil reserves – at the next available opportunity – to engage in a decisive fight with the British. This was intended to give Mussolini the strategic Mediterranean victory that he had long sought. That opportunity had now presented itself. News of the Italian sortie alarmed the British. The oldest of their fears — that one day, the Italians will mobilize their full strength to bring a convoy to a stop — was now threatening to manifest.

A mass of Italian aircraft swarmed Halberd at noon on 27 September. Lines of Axis torpedoes raced through the water at all angles, plunging into several escorting warships. By late afternoon, the Italian fleet was in position to attack the haggard remnants of the British force. But the Italians themselves had become disarrayed by misty conditions over the sea and contradictory reconnaissance reports. They turned back without attacking. The British were bewildered — and elated.

They could “have eaten up the convoy without the slightest difficulty,” said Vice-Admiral James Somerville, the escort commander. Halberd reached Malta on following morning. It disgorged 60,000 tons of supplies. Island morale soared, but everyone knew that this optimism would last only as long as islanders thought that another convoy will follow.

Frustrated by their inability to sweep the RAF from the skies, the Italians introduced a high-performance fighter aircraft into operations. These Macchi MC202 Folgores (Thunderbolts) were equipped with a powerful German engine, the Daimler-Benz DB601A.

The first Folgores entered Italian service with the veteran 9th Group on Sicily in September 1941. The Italians were inordinately proud of their new fighter, a beautiful, streamlined aircraft with the pedigree of a sports-car, boasting cockpit armor and self-sealing fuel tanks but badly let down by two, slow-firing .50-caliber machine guns — although after the first 400 machines, an additional two 7.7mm machine guns were added to the wing. The Folgore had a top speed of 374 miles per hour at over 16,000 feet and a climb rate of 3,546 feet per minute.

Long before any RAF pilot on Malta ever saw a Folgore, rumor ran rife that the aircraft used the same engine as the Messerschmitt Me109 and was just as fast. Some pilots attempted to couch their nervousness amid bravado. “Eyeties were eyeties,” Tom Neil said. But these Eyetie aircraft were a new breed, as the pilots of the RAF’s 185 Squadron discovered on October 1.

Ambushed by the Italians, the British squadron found itself in a sprawling wheeling dogfight. The Italians shot down and killed Peter “Boy” Mould, the island’s most popular squadron commander. Mould was a celebrated former athlete and an ace from the Battle for France. His death sent even Lloyd into mourning.

Yet, the mourning period was short. Lloyd had bigger problems. The heavy autumn rains brought construction work at the airfields to a grinding halt, wiping out much of the hard work of cutting and excavation achieved over the summer. The airfields turned into a sea of mud and only the dedication of the ground crews and labor teams, who toiled endlessly under the driving rain helped to keep them open. Incidences of jaundice, fever and pneumonia soar. Rainstorms, however, did not interrupt the activities of the Royal Navy.

On 21 October 1941, Vice-Admiral Wilbraham Ford, the naval chief on the island received two cruisers and two destroyers, collectively titled Force K. These vessels were to increase the sink rates of Axis convoys. Whereas the Italo-Germans had suffered the loss of 20% of their cargo in October, Ford intended to use Force K to amputate Rommel’s lines of supply in November.

Force K, October 1941

| HMS Aurora | Capt. W.G. Agnew | HMS Lance | Lt-Cdr R.W. Northcott |

| HMS Penelope | Capt. A.D. Nicholl | HMS Lively | Lt-Cdr W.F.E. Hussey |

A British intelligence reported that a convoy of seven ships was due to sail from Naples for Tripoli on November 8. Ford sent Force K to intercept. The result was spectacular. Every Axis freighter in the convoy was destroyed.

The results of the engagement… [are inexplicable]. All, I mean, all our ships were sunk. The British returned to their ports after having slaughtered us.

Count Ciano

At Hitler’s headquarters, the mood was one of disbelief. On the following day, Rommel complained to Berlin that his supply line had been severed as a result of Force K’s attack and that only 8,093 troops out of the 60,000 promised had arrived so far. A day later, the Italians ceased all direct traffic to Tripoli, falling back on their secondary, eastern route to Benghazi, an untenable, long-term solution. Something clearly had to be done if catastrophe was to be prevented from overtaking the sea lanes to North Africa. General Walter Warlimont at OKW (German High Armed Forces High Command), asked that a new fliegerkorps be redeployed on Sicily. Hitler agreed and on December 2, the battle-hardened Fliegerkorps II, which had spent the year campaigning on the Russian front, began transferring to Sicily.

In the meantime, a two-freighter British convoy with 10,000 tons of supplies sailed unescorted towards Malta in November. The ships never arrived. Italian aircraft had torpedoed both vessels. With winter coming, Dobbie and the governing council had no option but to scrap a plan to increase rations for Christmas. They were aware that London had no plans to dispatch another convoy until the following year. Worse news followed. A realistic assessment of food stocks on the island resulted in a memorandum urging immediate, large-scale rationing to allow the population to get through the winter. Dobbie also introduced price controls to rein in the runaway cost of food, thanks in part, to a thriving black market.

The average officer pilot could afford the black-market; the average Maltese faced bankruptcy if they tried. A new government advisory board recommended fixing prices of essential commodities at or near pre-war levels. Regional Protection officers were instructed to ensure that businesses follow fair pricing agreements.

Arresting price inflation on Malta with fixed prices, November 1941

| Old Price | New Price | Old Price | New Price | ||

| Bread | 3½d | 3d | Matches (1 box) | 2d | 1d |

| Tomato Paste | 9d | 6d | Bottle of edible oil | 8½d | 6d |

| Sugar | 6d | 4d | Tin of Milk | 9½d | 7d |

| Lard & Margarine | 1s 8d | 1s | Kerosene (1 gallon) | 1s 3d | 1s |

| Soap bar | 4d | 3d | Coffee | 1s 2d | 10d |

All servicemen were required to follow the new price guidelines but the fighting men of the RAF and the Royal Navy faced less stringent rationing. For submariners, the rules were slightly different. Boats out on patrol enjoyed good meals from well-stocked stores.

The winter, however, ushered in more bad news for Malta. The venerable aircraft carrier Ark Royal, which had formed the backbone of Hurricane deliveries (known as “Club Runs”) to the island in 1941, was sunk by a German U-boat. The carrier’s contingent of Hurricanes, which had fortunately taken off before she sank, were the last factory-fresh Hurricanes to ever reach the island.

With no more reinforcements to be had, Lloyd was allowed in mid-December to temporarily “hijack” two half-squadrons of Hurricanes which were on their way to Java to combat the Japanese Far Eastern juggernaut. But the RAF was discomfited by increasing numbers of Macchi Folgores roving over the island and by reports of Fliegerkorps II filtering into Sicily with high-speed bombers and potent Messerschmitt M109 fighters. RAF pilots once again asked Lloyd to write to the Air Ministry to send Supermarine Spitfires before it was too late.

Lloyd was enraged. “It isn’t the aircraft. It’s the man,” he said. Flight Lt. Tom Neil had to physically restrain himself from lunging at Lloyd.

Morale plummeted, but for some pilots, the nightmare was almost over. Their three-month tour of duty had expired and they were going home. Neil was among them. His relief was palpable.

Force K and Malta’s submarines dominated the central Mediterranean that winter, even as Enigma decrypts revealed Rommel’s desperate fuel situation. Rommel travails were enhanced by a British counteroffensive in the desert codenamed Crusader, which aimed to breakthrough to the besieged city of Tobruk.

In desperation, the Italians resorted to sending waves of small, two to three-ship convoys to Rommel, which achieved little. Sixty-two percent of supplies destined for Rommel went down with the merchant ships in November, as did 92% of badly needed fuel — a staggering accomplishment enabled almost single-handedly by Force K. This struck the high note of British anti-shipping endeavors in the Mediterranean. With the arrival of Fliegerkorps II in the theater, however, things were about the change.

The German redeployment in Sicily coincided with the arrival of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring as commander of the Axis Southern Front. Kesselring has fought the British before, during the Battle of Britain, when he had commanded Luftflotte II (Air Fleet II). This force was responsible for inflicting much of the devastation wrought on southern England and London in 1940. Kesselring was quick to realize that Malta represented the Battle of Britain in miniature and that this gave the Luftwaffe the unique opportunity to rectify its previous mistakes.

He arrived in Rome on 28 November and was presented with Directive 38, Hitler’s vision for the Mediterranean.

Hitler’s Directive 38, 2 December 1941

- In order to secure and extent our position in the Mediterranean and to establish a focus of Axis strength in the Central Mediterranean. I order, in agreement with the Duce, that part of the Luftwaffe no longer required in the East be transferred to the South Italian and North African areas, in the strength of about one Air Corps with the necessary anti-aircraft defense. Apart from the immediate effect of this improvement on the war in the Mediterranean and North Africa, efforts will be made to ensure that it has considerable effect upon further developments in the Mediterranean area as a whole.

- I appoint Field Marshal Kesselring to command all forces employed in these operations. He is also appointed Commander-in-Chief South. His tasks are:

- To secure mastery in the air and sea in the area between Southern Italy and North Africa in order to secure communications with Libya and Cyrenaica and, in particular, to keep Malta in subjection.

- To co-operate with German and allied forces engaged in North Africa

- To paralyze enemy traffic through the Mediterranean and British supplies to Malta and Tobruk, in close cooperation with the German and Italian Naval forces available for this task.

- Commander-in-Chief South will be under orders of the Duce whose general instructions he will receive through the Comando Supreme.

- The following will be subordinate to commander-in-chief South:

- All units of the German Luftwaffe stationed in the Mediterranean and North Africa.

- The air and anti-aircraft units at his disposal for the execution of his tasks by the Italian Armed Forces.

For the execution of the tasks assigned to him, commander-in-chief South is authorized to issue directives to the German Admiral Group South (for eastern Mediterranean).

— Adolf Hitler

Meanwhile, a violent storm raged in the Mediterranean that December, lashing ships at sea, sending merchantmen scurrying for harbors and grounding aircraft on Malta. There was barely enough tinder to keep Maltese fireplaces going and shortages of coal interfered with the preparation of food. Electricity was erratic and such was the scarcity of commodities that even the black markets had bare shelves. In this sepulchral atmosphere, the first of Fliegerkorps II’s aircraft start appearing in the region.

When Force K reported that it was nearly out fuel, the Admiralty sent the Breconshire, a high-speed, deep-capacity tanker from Alexandria to provide replenishment. The tanker was escorted by several cruisers and destroyers under Vice-Admiral Philip Vian.

A massive Italian convoy, codenamed M42, also happened to be sea on a collision course with the British. When the Italians discovered this, they scrambled their fleet and a mass of aircraft to attack Vian. A series of disconnected struggles and events ensued: Warships from Malta blundered into an Italian minefield and were destroyed; Vian found himself under withering fire from the Italian navy for 11 minutes (an engagement recorded as the First Battle of Sirte). At Alexandria, Italian frogmen planted explosives on British warships in the harbor, crippling two battleships. In the midst of this drama, Breconshire reached safety as did the Italian convoy, M42, providing Rommel with enough supplies and men to mount a second counteroffensive towards Tobruk.

Back in England, George Beurling was posted to No 57 Operational Training Unit, staffed by the legendary “few” of the Battle of Britain. Beurling was in awe of his instructors, all of whom were combat veterans, especially the heavily decorated Flying Officer James “Ginger” Lacey who was renowned at the time as the greatest ace of the Battle of Britain. However, few of the staff were impressed by Beurling’s exuberance or his physical appearance – his tendency to dress loosely with a long lock of sandy-blonde hair hanging over his temple, a scarf wrapped lackadaisically around his neck.

Once airborne, however, Beurling quickly showed his aptitude for flight. “He flew his Spitfire…as if he’d been born it,” remarked his instructor, Sgt. Tony Pickering.

Beurling was classified during training as “above average” but he turned down Lacey’s offer of a commission. “I feel like a pilot, not an officer,” Beurling said and no one knew what to make of him. But what they didn’t know, Beurling had realized early on: all he desired was to prove his mettle against his adversaries in the crucible of battle. Medals and promotions meant little to him.

Persistent German air reconnaissance over Malta tipped Kesselring’s hands that he was about to launch a new air offensive. The island was soon swarmed by a mass of German fighters and bombers from December 19.

British losses began to spiral out of control. “The Hurricanes were easily outnumbered and their performance was not equal to that of the new Me109s,” said Lloyd, admitting that perhaps it was not the man after all, but the machine.

“Our answer…should have been the Spitfire, but not one was allowed out of Britain,” he added.

By New Year’s Day, 1942, the Luftwaffe had successfully carried out Malta’s 1175th air raid since the start of the island’s war on 11 June 1940. It was only the end of the beginning.

I was very interested to read your notes on Ronald Chaffe. I am currently writing a definitive history of Bristol Rugby Club, and he played one game for us in 1935-36. No official list has survived of the club’s WW2 fallen, but I knew he was one of them. However, I only knew he had died off the coast of Malta, so your notes have been of great value and will be acknowledged in the book. The only other info I have on him is that he attended Cotham School in Bristol and is listed on the war memorial there.

Mark Hoskins

Historian Bristol Rugby

Glad to be of help.

Yeah, Ron Chaffe was a very colorful character. His untimely death was the stuff of a Homeric tragedy. Completely unnecessary.

I have additional information about his time on Malta which could be of interest – although it may not be pertinent to your book.

Thank you so much. Anything else you have would be of interest. I know so little about our WW2 casualties. You may well have a couple of gems I might use.

Hi Mark,

I’m away from home, on assignment, at the moment. I’ll get you more information once I’m back.

Thank you. Absolutely no rush.

Evening, Ronald John Chaffe was my Grandad’s brother. I would love to know more about his time in Malta. I am visiting in December. Thanks, Olivia

Hi Olivia,

Thank you for your message. We can wait for Mark Hoskins to also weigh in on this, but unfortunately, Ronald Chaffee did not get to spend much time on Malta.

He arrived on Malta on 21 Feb 1942, with a group of nine pilots from Gibraltar. Assigned to command No 185 Squadron, he was thrust into his first combat action on the following afternoon.

He was chasing a Junkers Ju88 bomber when German Messerschmitt fighters shot up his Hurricane from behind. He bailed out and members of his squadron saw him in his dinghy about five miles south of Delimara Point. The British had fast rescue boats that were sent to speed out and pull downed pilots from the sea. On this occasion, however, one of the available rescue launches refused to go out because German fighters were around and the Germans were known to strafe the boats. An Air-Rescue flying boat could also not be dispatched at the tome as RAF fighters were too enmeshed in combat and could not provide cover. Therefore, a proper search for Chaffe could only be conducted that evening. The next senior officer in the squadron, Flight Lt. Rhys Martin Lloyd, led a flight of four Hurricanes on the search mission. But it was getting dark and they couldn’t see Chaffe’s dinghy.

Rhys Lloyd tried again after breakfast the following morning, with a force of nine Hurricanes and a Martin Maryland. A squadron of German fighters bounced them. Heavy fighting ensued and the search mission returned to base after combat ceased – having been unable to search for Chaffe. When a second search mission was tried a few hours later, it encountered more German fighters. But a rescue launch was finally dispatched to collect new fliers reported in the water. The launch found two seriously wounded Germans and the body of a third. There was no sign of Chaffe or his dinghy. Sadly, no trace of him was found.

I am very interesting in learning when this book will be published.

Thanks for the interest,Steven.

The book is almost complete, but I’ve been caught up in a side book project on nature for an organization – which has taken a protracted amount of time to finish.

Nevertheless, I plan to wrap up “Malta” by June and hope to move it on to the publishing stage by the end of the year.

Thanks for the information. I would be very interested in purchasing a copy if you will let me know who is selling it.

I’ll post the information on this page when it’s out. Thanks.

Very comprehensive history of the Malta disaster. My father flew Hurricanes there Nov 1941 to March 1942. Lloyd told them on parade that they (pilots) were dispensable.

A very comprehensive history of the Malta disaster. My father flew Hurricanes there from Nov 1941 – March 1942. Lloyd told them (pilots) on parade that they were dispensable. Tragic loss of life.

Thank you for your message. Yes, Lloyd was a complicated, bizarre figure who was almost theatrical in nature. What is your father’s name, if I may ask?