1942, The Turning Point

A massive battle erupted over Grand Harbor on 10 May. A smokescreen covered the Welshman at her moorings. The smoke was a novelty which the defenders of the island have never seen before. It was an ally. Said Gunner Stan Fraser is a member of a 3.7-inch AA gun battery: “About 30 bombers are reported to be approaching the island. The stage is set and gleefully we await the entrance of the villain, having laid a trap for him.” An unprecedented number of British fighters were airborne — 37 Spitfires and 13 Hurricanes. By the afternoon, the number of Spitfires available for combat had risen to 42. Shocked and overcome by the sprawl of Spitfires, the Germans lost a dozen aircraft by dusk.

Barnum & Bailey have nothing on the show we witnessed. Stukas diving…Spitfires circling…Ju88s bombing. The sea from Malta to Sicily looked Henley Regatta; there were so many German crews in their dinghies.

Corporal Cyril Wood

But the British had not come through unscathed. Three Spitfires had been destroyed and one pilot killed.

The day, recorded in the annals as the “glorious 10th of May,” was a decisive victory for the Allies at a time when there were none to be had. The islanders wept with joy to see the Axis bleed in this manner. The islanders took the Axis casualties as retribution for the deaths of 1,104 Maltese since the start of the war and for the destruction of Floriana and Valletta which had been largely deconstructed into 1,500,000 tons of debris.

RAF Tally, 10 May

| By Fighters | By AA | |||||

| Destroyed | Probable | Damaged | Destroyed | Probable | Damaged | |

| Ju87 Stuka | 9 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Ju88 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Me109 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Z1007bis | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – |

| MC.202 | 1 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Total | 20 | 16 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

Despite Malta’s resurgent nature, that same evening Kesselring signaled Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia reiterating that: “Enemy naval and air bases at Malta eliminated.” Never mind that between May 10-12, the Axis would lose more bombers than during the whole five weeks of the main offensive from March to April in the course of 11,500 sorties.

Kesselring’s optimism worked against him. Believing that Malta was finished, Hitler finally executed his plans to withdraw several air units to other fronts. Kesselring found that he had the ignominious honor of making preparations to transfer I/JG3 and II/JG 53 to Russia; III/JG53, III/StG3, III/ZG26 and the Ju88 night fighters of I/NJG2 to bases in Libya to help Rommel, and lastly, the bombers of I/KG54 to Greece. The result was an abrupt decline in German air activity over Malta from May 13.

With the siege still in effect, however, and with London’s refusal to send a convoy in May, citing the lack of a battleship for protection, Malta’s stockpiles diminished.

Adult males on the island were restricted to a 1,500 daily calorie diet at a time when working males require 3,000. Women and children have to make do 1,200 calories. “In April, most belts had to be taken in by another two holes and in May, by yet another hole,” Lloyd said.

In neighborhoods and streets, there is a pervasive sense of being trapped in a climate of death, destruction and horror. “We thought we would never be able to get out of Malta,” said a British expatriate stuck on the island since the beginning. Food was so scarce that even household pets were turned out and become competitors for what little food was available.

The government seized upon collective feeing as the answer and a series of communal (Victory) kitchens open across the island, although patrons complain about the poor quality of food. “Why should Hitler invade?” went a popular gaffe. “We’re all prisoners on Malta already.” — A view ironically shared by Hitler.

When some German commanders escalated their demands for invasion, Hitler flew into a rage. On May 21, Kurt Student traveled to Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia, to deliver a presentation on Herkules. He expressed his confidence that it would succeed. His view was backed by the Navy and by the chief of staff of the Luftwaffe, General Hans Jeschonnek. The Italians were so enthusiastic that they had already formed a special Inter-Allied Malta Staff in Rome to coordinate the invasion. The staff had already started to allocate forces for the assault.

The staff made noble plans: Herkules was to be supported by 222 Italians and 189 German fighter aircraft, 474 Italian and 243 German bombers, and 170 Italians and 216 German transport planes. The airborne forces amounted to two Italian parachute divisions and the German 7th Fallschrimjäger Division. The La Spezia division was to be flown-in once the island airfields had been secured.

Once the landing beaches were under control, a motley collection of 151 barges, trawlers, ferries, motorboats and landing craft were two transport the Friuli and the Livorno divisons to the island along with the marines of the San Marco regiment. Two more Italian divisions were to be held in reserve. Ninety-six thousand men in all. And all backed by the Italian fleet under Iachino, the “victor” of the Battle of Sirte. In contrast, the British had their Mediterranean Fleet in distant Alexandria, and 26,000 men on Malta.

An irate Hitler declared that all the plans and proposals that he had been shown, ran “counter to his ideas.

Like a mythical bird rising from the ashes, Malta resurfaced from under the rubble and her aircraft begin to strike Axis convoys again. New Spitfires streamed into the island in the first week of June to replace the losses of May. On 3 June, Operation “Style” saw 31 Spitfires launch from HMS Eagle.

Led by three Malta veterans, Johnny Plagis, Jimmy Peck and Tony Barton, the flight was initially uneventful until German Messerschmitts appeared near Pantelleria. Several RAF pilots observed 12 Me109s (from II/JG53) watching them from a distance. It was the first and only time in the history of the Spitfire “Club Runs” that the Luftwaffe affected an interception.

A former air-rescue pilot, Flight Sgt. Tom Beaumont, shouted over the radio that the Messerschmitts were coming in. Sgt. Len Reid from Australia looked to his flight leader, Johnny Plagis, whom he had been told was a great ace, for guidance. To his shock, Plagis, rolled over and abandoned the flight, leaving them to their fate. The Messerschmitts let Beaumont have it. He inched forward until he was beside Reid as if beseeching for help when his aircraft erupted into flames. It turned over and plummeted into the sea.

Reid had problems of his own. Tracer rounds flash past his cockpit. He dove to build up speed. The Germans followed him straight down, blazing away without hitting him. Reid managed to give them the slip and heads in the rough direction of Malta.

Another section under Flying Officer Bob Middlemiss (a Canadian) was also in trouble. With no way out, the section executed unending defensive circles, edging closer and closer to Malta, before they could make a dash for safety. Four Spitfires were shot down in total, including Beaumont’s. Another Spitfire crash-landed on Malta but Plagis arrived safely, where he was informed that he had been promoted to flight lieutenant and transferred to 185 Squadron.

Several of the new arrivals were truly men of caliber. Three of the new arrivals, including Jones, Ramsay, and Middlemiss, went into 249 Squadron. The most experienced of them, Pilot Officer Gray Stenborg, a New Zealander with four victories, went into 185 Squadron. The most dangerous of them, Pilot Officer Henry Wallace “Wally” McLeod, went to 603. McLeod, a sharp-eyed, ice-cool Canadian, harbored aspirations to become his country’s greatest fighter ace. What he would engender, however, was a reputation for being a “cold-blooded killer.”

George Beurling arrived on the island on 8 June as part of Operation “Salient,” a 32-strong Club Run of Spitfires which again launched from HMS Eagle.

No sooner had Beurling landed on Malta when he was astounded to see a trio of Messerschmitts “come whipping out of nowhere,” just 10 feet off the ground, their guns blazing before masterfully dodging the ack-ack to make their escape.

Beurling was anxious to begin operational flying but his reputation for unconventionality had preceded him. No squadron wanted him. He realized that someone has poisoned the well against him and that his old nickname from England — “Screwball” had followed him to Malta. Word also spread that Beurling’s other nickname was “buzz” because he liked to “buzz” things.

Lord Douglas-Hamilton of 603 wanted nothing to do with Beurling having been told that he was “a rather crazy pilot and a line-shooter.” He was also unimpressed with Beurling’s slipshod manner of dress and what with his wearing “a lock of his long, sandy hair hanging over his brow.” Douglas-Hamilton held a coin toss with Stan Grant of 249 between the choice of Beurling and another pilot. Beurling went to 249 Squadron.

Bob Middlemiss, now a member of 249, was surprised and concerned to learn that Beurling was joining his squadron. “He tends to get separated from the squadron,” he warned the flight commanders, Laddie Lucas and Buck McNair. “Very individualistic, a little bolshy… He’ll either buy it very quickly here or shoot some down.” It is on this opinion that McNair, promoted to command B Flight after MacQueen’s death, refused to accept Beurling and suggested that he be shipped back to England. Grant instead assigned Beurling to Lucas’ A Flight.

Beurling redeemed himself on the next day when he broke an attacking Messerschmitt in half, and saving the life of squadron’s sole Anglo-Indian, Pilot Officer Owen Berkeley-Hill, who was on the verge of being shot down.

Coming to the island is like coming awake from a pleasant dream into the heart of an earthquake.

George Beurling

Churchill, meantime, was anxious to return Malta to its erstwhile status of “lynchpin.” He authorized a double convoy to bash through to the island. This would set the stage for a massive battle at sea.

Churchill’s double convoys, named Harpoon and Vigorous, with a total of 17 freighters between them, were backed up by a battleship, two aircraft carriers, 40 destroyers plus the surviving submarines of Simpson’s Tenth Flotilla now operating out of Alexandria. Aircraft at Gibraltar, Libya and Malta were also available for support. Sailing from either end of the Mediterranean, the convoys hope to divide the enemy and tease out the Italian fleet where it can be mauled by the powerful British escorts.

Churchill also intended to use the convoys to test the mettle of the Mediterranean Fleet’s new commander, Admiral Sir Henry Harwood, who had replaced Cunningham following the latter’s transfer to Washington D C on a diplomatic mission.

In Egypt, a veteran Bristol Beaufort pilot, Squadron Leader Patrick Gibbs, was summoned with other officers for a conference at the headquarters of 201 (Naval Cooperation) Group in Alexandria. They were briefed about the incoming ships. The orders were to prevent a possible intrusion by the Italian Fleet. “I need hardly tell you, gentlemen that the fate of Malta may depend on the success of this operation,” the group commander said.

Since mid-1941, a steady stream of Beauforts, Beaufighters, Hudsons and Blenheims had been sent out to North Africa and Gibbs fully expected to find a position with a fully-staffed and operational squadron or perhaps even to take command of a squadron.

To his shock, he discovered that the strike force in North Africa was “microscopic” and that a Beaufort pilot, no matter how experienced, was unwanted. This was how he had come to find himself becoming a semi-permanent fixture at Air Headquarters, Cairo, watching the war go by via labels placed on maps, and turned down by every strike squadron in the land — that is, until his eyes fell on 39 Squadron flying Beauforts from a dusty airfield in the western desert.

The squadron was trying to forge a miniscule reputation for itself without much success. The entirety of its wartime experience amounted to just two strike operations — one on January 23 during which it sank a destroyer and the other on March 9, when it shot down a German Ju88. But on April 14, when the squadron mounted its third torpedo operation against an Italian convoy and promptly lost seven out of nine Beauforts, Gibbs saw his chance to transfer to the squadron. His machinations paid off. In Late-April, he was ordered transferred to “39 Beaufort squadron (what’s left of it).”

The squadron was a mess. Yes, the Beauforts, unwieldy like London buses, were at the mercy of enemy fighters, but the squadron had shot its own bolt through halfhearted operations. Gibbs was aghast to discover the squadron only operated once a month, whereas a similar squadron in England operated once a week. Aircraft serviceability was low because the desert sand got into everything and the scorching desert heat had an enervated effect on the minds of men.

The only way for the squadron to improve was to fly frequent operations, obtain more modern Bristol Beaufighters for escort and perhaps get the improved, Mark II version of the Beaufort. The squadron’s existing Mark I aircraft struggled to attain 150 mph in the desert heat when their top speed should have been 270 mph. Some Mark IIs did arrive soon enough, as did increasing numbers of Beaufighters in May.

On Malta, itself, Lloyd had only the Naval Air Squadron at Hal Far. that could be used to protect the convoys. Then, nine Beauforts from No 217 Squadron arrived at Luqa on June 10. They were en-route to Ceylon where the rest of their squadron was gathering. Lloyd hijacked them without a second’s thought, as he he did a following flight of six Beauforts on the following day. Neither the Air Ministry nor the unit skipper, Wing Commander W.A.L. “Willie” Davis, were amused. Lloyd admitted in his postwar memoires that his hijackings (he calls them “wranglings”) gave Malta a bad name and that the nickname “Sticky-Fingers” stayed with him well after the war. But he argued that his actions were “boyish pranks” aimed at keeping Malta in the fight:

Some reinforcement aircraft would ‘accidentally’…find their way into our pens and the older ones would be sent ‘in exchange…this high-handed action [was extended] to more experienced crews, particularly if they had friends on Malta or had volunteered to stay.

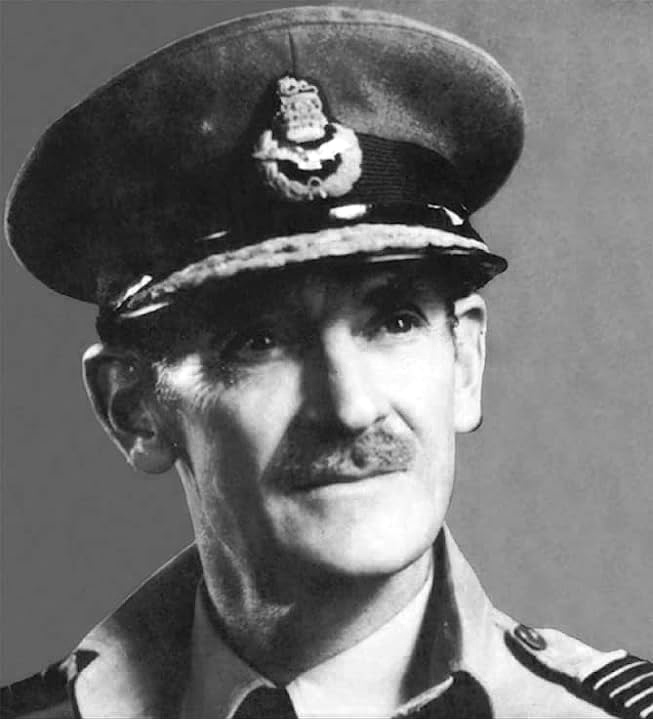

Air Vice Marshal Hugh Pughe Lloyd

Few men in 217 Squadron, however, volunteered to stay. For one, they were all green; just two men in that great congregation of air crews had any experience. Their Beauforts are also unfit for combat. Internal machinery required servicing and that none of the aircraft had torpedo launch equipment which had been removed to make room for an extra fuel tank in the bomb bay.

Meanwhile, Harpoon formed in Scotland; Vigorous at Alexandria and Haifa. Both faced a formidable foe in the form of the Italian navy which had learned much since 1941. The Italians, however, also understood the difficulty of sortieing against convoys protected by battleships and aircraft carriers. So, when on June 13, their intelligence identified the makeup of the convoys, they decide to use their airpower, submarines and fast torpedo-boats against the carrier and battleship-heavy forces of Harpoon, while pitting their heavy fleet units against the cruiser-heavy eastern convoy (Vigorous).

Harwood quickly showed that he was not Cunningham’s equal. When Vigorous, transporting 72,000-tons of supplies, drew the attention of the main units of the Italian fleet, his nerves failed. On 15 June, the British unleashed their airpower on the Italian fleet. Harwood believed the planes would send Iachino packing.

Awoken from their insouciance, the Italian anti-aircraft gunners opened fire but a first wave of attacking Beauforts from No 217 Squadron had already launched their munitions and were already racing away. The ack-ack was still active when five Beauforts led by Wing Commander “Willie” Davis arrived moments later. As a smokescreen enveloped the Italian heavy cruiser Trento, which had just taken a torpedo hit, the British aircraft ranged over the Italian fleet, dodging the ack and dropping their torpedoes at the big ships.

Lt. Ted Strever, a hearty young South African, mustachioed, tall and burly, went in low with the hopes of nailing a battleship. He dropped his torpedo and ordered the navigator, Pilot Officer Bill Dunsmore, to open fire with forward Vickers gun in the glass nose. To Strever’s dismay, the torpedo just missed the bow of his target and the ack-ack rose up to greet him. “The flak coming at us from all these was indescribable,” he says. “There was tracer, green, orange, blue…the water boiled around us. Big black shell bursts exploded.”

There was a loud crash above his head and the top hatch went flying off with shrapnel peppering the instruments and shattering the glass. A 20 mm shell hit the wing root, perforating the middle fuselage with steel splinters. The mid-turret was smashed and the gunner, Sgt. Bob Gray cried out in pain as shrapnel cut open his thigh.

Strever raced out of the cauldron of fire and limped back to Malta, his radio knocked-out and his instruments lying in a jumble on the cockpit floor. He belly landed at Luqa and once back in the safety of his billet, was overcome by terror. “Every time I closed my eyes I could see streams of tracer, hear the explosions and feel the buffeting of the blasts,” he said. “I lay on my bed and thought ‘well if this is what we are in for, we are not going to make it through this lot’.”

Iachino and his men were surprised by the aggression of the attacking Beauforts, although he admitted that violence of his anti-aircraft barrage and “the quick maneuvering of the battleships had disoriented the attackers, causing them to scatter.” Harwood, who had staked much on these airstrikes, was appalled to learn at 9.28 that the Italian Fleet is still intact and sailing towards what Iachino called, “Alpha Point,” where he could expect to meet the convoy.

Harwood ordered Vian to reverse course at 9.40 AM. This was the third time in less than 12 hours that Vian had turned around his naval force. The two remaining Allied airstrikes launched on schedule. At 4.30 AM, nine B-24 Liberators (two among them belonging to the RAF and the rest from the US Army Air Force’s “Halpro” Detachment), took off from Fayid Field near the Suez, on a historic first for American air operations in the Mediterranean. They were followed at 6.25 AM by the Gibbs and 39 Squadron with orders to land at Malta afterwards.

Iachino was kept abreast of the situation by German reconnaissance reports but the Gibbs’ Beauforts took him by surprise at 9.40 AM. As the lower skies filled with flak bursts, a lookout reported high-flying bombers approaching. The pit of Iachino’s stomach dropped. “We barely had time to look up when we saw around us several large columns of water rising up from either side of bow,” he said.

A 500-lb bomb hits Iachino’s flagship, the battleship Littorio, killing a man, wounding twelve, knocking the turret out and shaking a nearby catapult so violently that the floatplane atop it fell to pieces. Another bomb fell close to Vittorio Veneto. The jubilant Americans withdrew; convinced that they had mauled the Italian fleet. As they departed, Gibbs’ Beauforts come in.

Twelve Beauforts had taken off in four sections, with the squadron CO, Wing Commander A J Mason, leading two sections, Flight Lt. Alastair Taylor leading one with Gibbs as his wingman and the last one being led by another long-time squadron member, Flight Lt. Tony Leaning.

The sections led by Taylor and Leaning had new Beaufort Mark IIs while the sections under Mason had older Mark Is. The plan was to divide close to the target and attack in two waves. But Mason’s older Mark I had crawled along, infuriating Gibbs who had to throttle back to 120 knots and drop flaps to stay in formation. The ante was upped when messages flashing from the other aircraft demanding that they go faster, resulted in no change.

Gibbs became convinced that Mason’s former career as a flying-boat pilot was responsible for his incompetence. Just then, a nightmare became reality. Gibbs’ gunner warned of approaching single-engine fighters. Suddenly, two Beauforts fell out of formation on fire and the neat formation turned into a ragged circus. Five Beauforts aborted after suffering damage, leaving just five headed towards the objective.

As they approach the Italian Fleet, long-range flak bursts bracket the Beauforts. These are not small bursts but a wall of exploding shells with “innumerable lines” of tracers drawing against the sky.

With sweat pouring down his face, Gibbs dodged the ack-ack in a desperate attempt to avoid being hit, even as he mentally registered 25 ships in the water before him. Somehow, he and the other planes penetrated the forward destroyer screen, although two aircraft took massive damage. Abruptly, as though he had entered the eye of the storm, the sky turned calm and no obstruction lay between him Iachino’s flagship, Littorio. A sense of slow-motion clarity creept into the imagery. Gibbs could see individual sailors walking calmly on deck as he dropped his torpedo.

Time accelerated to super speed as he turned his Beaufort to escape. The whole side of the battleship came alive with gunfire. Tracers flew at his aircraft and the water turned into “a cauldron of foam.” A terrific explosion sounded near the bomb-bay accompanied by sound of metal being shredded. Yet, Gibbs escaped the maelstrom and reformed with a solitary Beaufort flying nearby. It turned out to be Mason. Both aircraft headed towards Malta, soon joined by a third Beaufort. Malta, replenished by spring rains, was luxuriant and green, a welcome contrast to the yellowed tan of the desert.

Gibbs’ hydraulics refused to engage so he belly-landed on Luqa’s main runway only to be confronted by a hopping mad Wing Commander who told him: “Damn it man, this sort of thing is usually done on the grass.”

Meanwhile, Harwood’s dithering prompted Vigorous to make no less than five 180-degree turns over the course of 24 hours. By the afternoon of Tuesday, June 16, the convoy was back in Alexandria, having never sighted Malta.

1942. An Imperial Balls-Up

Enemy aircraft swarmed the ships and crews of Harpoon nearly overcoming British carrier fighters which struggle to stem the tide. Heavy losses ensued on both sides. The convoy’s heavy escort then turned back for Gibraltar upon reaching the Skerki Banks, the narrow stretch of sea between Sicily and Tunisia’s Cape Bon.

To make matters worse, the Italian 7th Cruiser Division under Rear-Admiral Alberto Da Zara, one of the finest naval commanders in the Italian navy, entered the fray. This unit had two cruisers and seven destroyers. His opponents were Force X — am escort formation with the cruiser Cairo and 10 destroyers, under the senior-most British officer remaining with the convoy, Captain Cecil Hardy. Force X did not have the firepower or the experience to thwart Da Zara.

Although believing himself outnumbered, Da Zara engaged Harpoon. “The decision was not heroic, but rational and conscious,” he said later. “After [Italian defeats at] Punta Stilo, the Gulf of Genoa, Sirte, the second Sirte, the Regia Marina needed a ‘surface success’.”

Hardy released the five Tribal-class destroyers of his 11th Flotilla to attack Da Zara while he attempted to shepherd the vulnerable freighters to Malta, now about 80 miles away. Under Lt-Commander Bryan Scurfield, the Flotilla was green. But they were prepared to sacrifice themselves if it meant that the convoy could escape.

“This is what I have been training for 22 years,” Scurfield said. “…It is to my mind merely a question of going bald-headed and trying to do as much harm as possible by guns and torpedo.”

Scurfield and his command charged the Italians. Da Zara was full of admiration for Scurfield’s boldness but critical of his recklessness. Despite being 11½ miles from their targets and out of range, the British destroyers opened fire, their guns pointed high to compensate for their lack of range. Like a sage reading tea leaves, Da Zara studied the size of the geysers and concludes that he was facing warships armed with six-inch guns. In fact, the 11th Flotilla’s Tribal-class destroyers only had 4.7-inch main guns.

Abruptly, Scurfield’s command began to disintegrate. Two direct hits slammed into the bridge of his ship, the Bedouin, shattering her mast and destroying her radio aerials. Nevertheless, Scurfield pressed on to within 5,000 yards of the Italians to launch torpedoes in the face of withering enemy fire. Tracers filled the air; heavy shells carved translucent tunnels in the briny air. Scurfield turned the destroyer starboard and fired his torpedoes. No sooner were they in the water when Bedouin ground to a halt under the weight of fire. It was 7 AM on 15 June. Da Zara dodged the torpedoes but fearing another attack, he made smoke and moved away. The sight of their retreat filled Scurfield with joy.

“We were at least masters of the battlefield,” he said. It was to be a short-lived triumph.

Two Italian destroyers under Capt. Castrogiovanni, Vivaldi and Malocello, attacked the convoy independently. Vivaldi unleashed two torpedoes in the direction of the convoy and was rewarded by the sight of an American freighter, Chant, blowing up, unaware that the freighter had been hit by three German bombs. Chant meandered out of line, ablaze like a roman candle. It was on a collision course with another freighter, the Orari whose skipper, Captain Rice, ordered full speed to escape being struck. A moment later, Vivaldi came under accurate gunfire from Hardy’s Hunt-class destroyers. When a shell punched into Vivaldi‘s engine room, Da Zara ordered Castrogiovanni to withdraw.

By when air support from the island materialized in the form of two Beaufighters from 235 Squadron and eight Spitfires from 601 Squadron, “The Bish” Bisdee was astounded to find a major naval battle unfolding beneath him.

“Lots of Italian warships, some on fire, others firing on convoy and us,” he said. “Nineteen ships in convoy weaving like hell and taking a caning.” Seeing two ships close to the convoy, Bisdee flew low to identify them and discovered that they are the Vivaldi and Malocello. “Wish I had a bomb to drop down the funnel,” he remarked.

Meantime, Scurfield’s 11th Flotilla was fighting like a wounded lion. Ignoring a beating from Da Zara’s flagship, Eugenio, the British destroyers concentrated their fire on the cruiser Montecuccoli, which towered nearby as “if the central figure in a monumental fountain.”

As British shells straddled the cruiser, the Italians moved in to quash the threat. At 7.02 AM, a six-inch shell tore into a torpedo mount of Lt-Commander W. Hawkins’ Partridge, causing an explosion which hurled metal and flesh in all directions.

Partridge veered in a wide circle, out of control as Bedouin took a plastering from four shells one of which explodeds in her boiler-room and fractured a steam pipe. Eight more shells struck Bedouin over the next five minutes which de-masted her, destroyed her radar, broke her starboard engine and killed several of her bridge crew outright. Scurfield, however, had survived and ordered the ship to turn away.

With the two senior ships out of action, the responsibility of command fell on Lt-Commander D. Maitland-Makgill-Crichton and Ithuriel (a Canadian vessel). Maitland-Makgill-Crichton was a dashing blue-blood who was a master of languages, known to peers and subordinates as “Champagne Charlie.”

Bedouin later capsized. Some 209 men went into water. There, they were captured. Among them was Scurfield.

The convoy survivors reached Malta at 10 pm on the night of June 15 only to hit a minefield and suffer additional casualties. Only two cargo ships had come through out of six that had left Scotland. “An Imperial balls-up,” said one British gunnery officer and no one can think to contradict him.

In Malta, the disappointing result of the convoy prompted Gort to tell the islanders: “We must continue to stand on our own reserves.”

The Lt-Governor of the island, Sir Edward St. John Jackson, expounded on the crisis which the island now faced, warning of further privations and asking the Maltese to make more sacrifices. A crowd of Maltese descended upon Jackson’s residence at the Vilhena Palace and surrounded the building. Jackson perhaps expected a lynching. Instead, the Maltese serenaded him with accordions and guitars.

Amid legitimate fears that the island’s remaining stocks of food would not last past mid-August, Churchill made it clear to the British Chiefs of Staff that it was necessary “to make another attempt to run a convoy to Malta. The fate of the island was at stake.”

Just then, the Prime Minister was handed devastating news: Rommel had captured the coastal city of Tobruk on June 21, following a four-week slog.

News of Tobruk’s capture left the islanders shaken. With the allied lines pushed ever further east, the island was now a lonely bastion in the central Mediterranean. Rumors of invasion ran rife. The local government places its forces on high alert and the new governor, Lord Gort, who had a pathological fear of being captured, conceived fantastic plans to lead a force of volunteers on a suicide mission to Sicily. Even Kesselring expected the invasion to take place according to the timetable. Instead, he found Rommel in a roadman’s hut in Libya, planning an advance in Egypt.

Kesselring was outraged but Hitler backed Rommel. Operation Theseus was expanded to encompass the capture of Egypt. A humiliated Kesselring had no choice but fall in behind the venture, although he asked the Italians on Sicily to mount another blitz to keep Malta down in July.

The Italians also bolstered their forces on the island, sending the 20th Fighter Group on June 24, with thirty-six spanking new Macchi MC202s. Under the command of Major Gino Callieri, the group’s three fighter squadrons were staffed by men of varying quality. Callieri is well respected and known as the “cat,” not because he was stealthy but because he had caught, killed and eaten a cat on a bet during his academy days. But the best among them was Captain Furio Niclot Doglio of the 151st Squadron, a pre-war test pilot and the holder of nine aviation world records.

A trained aeronautical engineer, Doglio had been a pilot since 1930. He had flown operations over Southeastern England during the Battle of Britain, had seen extensive action in North Africa and had earned a Bronze Medal for Military Valor. He was a man treasured by the air force. As a fighter pilot, however, he was still an infant with a single victory over a Hurricane scored in 1941.

The arrival of the fighters was accompanied by Mussolini who had descended onto Sicily that same day to hand out medals and deliver pep talks. Coincidentally that same day, Lord Gort and Lloyd decorated their aircrews at an investiture at Castille in Valletta. Kesselring, meantime, was back in North Africa to throw his full weight behind the Suez venture. For the longest time, Malta had exercised control over events in North Africa. Now, North Africa had reciprocated by removing Fliegerkorps II from the central Mediterranean.

The Italians, backed by their smaller German allies in Sicily, however, planned a new air offensive. They hoped that this “July Blitz,” as it was known, would prove Kesselring’s belief that only fighter-bombers were needed to keep Malta in check. Instead, the blitz would test the mettle of the Italians to the limit.

Massive dogfights erupted over the island in July, presenting George Beurling with the sheer sprawl of chaotic combat that he had long dreamed about. He began to carve a great hole within the Axis ranks. Astounded, many of the veteran RAF pilots on the island watched his feats from the sidelines, having reached the end of their tours.

On July 10 — coincidentally the opening day for Herkules (which never materialized) — Beurling dove under a Me109 and pulled up, raking its underbelly with cannon fire. The Messerschmitt blew up, killing its pilot, Lt. Hans-Jürgen Frodien, a budding ace with four victories. Next, Beurling blasted a Macchi at the top of a loop. After the pilot bailed out, Beurling radioed the downed man’s position to air -sea rescue — contrary to his later reputation as a “killer.”

But the realities of war were catching up with him. On the next day, he was aghast to learn that a popular squadron pilot, Warrant Officer Chuck Ramsay, had been killed in action. Then on July 12, something happened which he would never forget. The catalyst was the death of the Anglo-Indian Flying Officer, Owen Berkeley-Hill, who was shot down moments after witnessing Hetherington shoot a Falco II. “I saw it, Hether, old boy,” Berkeley-Owens had said. Those were his last words.

Beurling, who had downed a Re.2001 Falco II flown by Lt. Francesco Vichi of the 358th Squadron in that morning’s combat, volunteered to join Hetherington in a search for Berkeley-Hill. Meantime, two MC202 Folgores, flown by the commander of the 2nd Fighter Group, Lt-Col. Aldo Quarantotti and his wingman (Lieutenant Carlo Seganti) scoured the sea for Vichi. Both flights ran into each other.

Slower than its contemporaries, the Folgore operated best at lower altitudes, although the Spitfire held the speed advantage at altitudes of 23,000 ft and higher. Therefore, the Italians had an advantage over the Spitfires rushing at them at low altitude, but they were sloppy and too preoccupied in their search for Vichi.

Hetherington climbed above the clouds to make sure that the Italians were not bait for an Axis trap while Beurling took on the duo. The first inkling the tall and Adonis-like Lt. Carlo Seganti had of danger was when his machine began shuddering due to point-blank firing from Beurling. Segenti’s Macchi erupted into flames. By when the machine began plummeting seawards, Seganti was already dead. Beurling next drew up on Quarantotti’s Folgore and closed to within 30 yards.

Quarantotti waggled to his wings as if to indicate that he was on a mission of mercy. He then turned and looked at Beurling and for a brief, terrible moment, Beurling could see “all the details on his face.” Beurling’s fingers instinctively pressed the gun button. Quarantotti’s head flew off. The body slumped forward. A macabre stream of red emerged from behind the cockpit canopy, staining the pale-colored fuselage.

The sight of this event would form a critical component of Beurling’s wartime and postwar PTSD, but he would not be able to understand what the memory was doing to him or why he woke up nights drenched in sweat. Instead, in the years to come, he would narrate this event to gushing female admirers, perhaps hoping to smother his horror in feeling in bravado. One, during an interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Company, he would declare that the image of Quarantotti’s headless body was a “great sight…the red blood down the white fuselage. I must say it gives you a feeling of satisfaction when you actually blow their brains out.”

The Italian high command initially believed that Quarantotti and Seganti had been killed in a collision. Both men were awarded posthumous Medaglias d’Oro (Gold Medals). When the truth emerged days later, however, Quarantotti’s men were thrown into despair. A further 48 hours after that, the Italian fighter group, already wracked by heavy losses in the past weeks, ceased to operate until a new commander could take over.

By this point, the German participation in the air offensive was nearly over even as the Italian component of the July Blitz came to a virtual standstill. In the first 13 days of July, the Axis had lost 102 aircraft shot down (according to Lloyd). During that same period, the RAF had lost 25 Spitfire pilots killed. In the second half of the month, only seven Spitfire pilots would die in combat, illustrating the diminishing nature of Axis air attacks.

Dusk on 15 July found Beurling sitting in the sergeant’s mess drinking juice. A figure darkened the threshold. It was Gracie, grinning strangely and acting fussy. Finally, he told Beurling that he has been awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) thanks to a recommendation by “Laddie” Lucas on 6 July 6. Beurling was surprised.

It was his first “gong,” but he never bothered to read the citation.

“Just a lot of words, you know,” he said later. But that first gong was something though. “You know what it means?” he said. “It meant all the time I spent trying to trip across Canada on the rods and the Seattle hoosegow and the long trek back. It meant my attempts to get into the Canadian, Chinese and Finnish Air Forces and three trips across the Atlantic in a munitions ship to get into the RAF. It meant all the months of training in England and the hell of a time I had to get posted to the front where I could get some fighting and prove myself to everybody else what I had known for years about myself…That DFM…that’s the one I treasure more than all the others. I won…that the hard way”.

As the July blitz petered out, Tedder replaced an exhausted Lloyd with Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park, the quintessential hero of the Battle of Britain. Park’s deft management of the fighters of the RAF’s No 11 Group in southeastern England in 1940 had blunted the Luftwaffe’s aspirations for success and had contributed to the collapse of the German invasion of the Britain. Park had also been responsible for carrying out much of the actual day-to-day fighting of that campaign.

In Lloyd, the Air Ministry had seen a man capable of taking the fight the enemy. In Park, it saw a man capable of blunting the enemy for good. The contrast between the two men was no clearer than when Park arrived on 14 July (during an air raid) and was agog at the scenes of devastation wrought by the Axis since January.

“Now you will see how Malta can take it,” said Lloyd, his chest puffed with pride. “Aren’t we brave?”

“I think you’re dumb,” Park retorted. “Why don’t you stop the bombing and get on with the war instead of sitting back and taking it?”

The fighter pilots greeted the departure of “Hughie-Pughie” Lloyd with relief but while Park was almost unanimously admired by the men under his command, he was less well regarded by his peers owing to a series of feuds during the Battle of Britain over tactics.

Within a day of his arrival, Park decided to silence his critics by doing what he did best — defending the realm. He proposed a new “Fighter Interception Plan,” designed to bringing the Axis bombing to a halt. Scrapping the existing system of scrambling fighters only when the raiders are halfway down to Malta, Park wanted them intercepted well out to sea.

For the job, Park had just four Spitfire squadrons: 126, 185, 249 and 603, plus 1435 Flight. He did not have the luxury of an aircraft reserve owing to losses. In the first 15 days of July, 36 Spitfires had been destroyed – roughly 40 percent of the Spitfire strength on the island. Three more had been damaged and several others were unserviceable. Fortunately, 31 Spitfires were flown in from Eagle on 15 July as part of Operation “Pinpoint.” These partly replenished the fighting strength of the squadrons. The Spitfires were all tropicalized Mark Vb versions with two 20mm cannons and four Browning 0.30-cal machineguns — a layout better suited for operations over Malta.

With just these units Spitfires (amounting to 50 fighters), Park intended to dramatically reduce the number of bombs falling on Malta.

Reflecting upon the island’s improved circumstance, Captain “Shrimp” Simpson and leading elements of the 10th Submarine Flotilla returned to the island on the night of 21 July. Simpson had been pleased to learn that the harbor and the channels were clear of mines. The food situation, however, was just as troubling as ever with the island being nearly out of all type of essential supplies, barring a trickle which continued to arrive via the “magic carpet” submarine service.

In July, the submarine HMS Clyde delivered 194 tons of goods, including 88 tons of aviation fuel to the island while HMS Parthian delivered 47 tons of ammunition, 36 tons of aviation fuel and 33 tons of other goods. Other submarines, HMS Porpoise and HMS Otus, also ran emergency stores from Alexandria. However, the bulk of these deliveries involved aviation fuel and not food. Gort worried that the Spitfires would not have enough fuel to protect the next convoy which was expected in August.

The resuscitated Tenth Flotilla on Malta

| From Alexandria | From Gibraltar | ||||

| P31 (Uproar) | Lt. J.B. Kershaw | Arrives 30 July | Unbroken | Lt. A.C.G. Mars | Arrives 21 July |

| P34 (Ultimatum) | Lt. P.R.H. Harrison | Arrives 30 July | United | Lt. T.E. Barlow | Arrives 22 July |

| Una | Lt. Pat Norman | Arrives 1 Aug | Unison | Lt. A.C. Halliday | Arrives 2 August |

| Umbra | Lt. Lynch Maydon | Arrives 15 Aug | |||

On 26 July, amid heavy combat in the skies, Park introduced his “Fighter Interception Plan.” The results, however, are less than satisfactory because RAF pilots have not had time to practice the new procedures.

The Fighter Interception Plan failed again on the next morning, 27 July, when 14 Spitfires are scrambled too late to stop nine Ju88 from bombing Takali. The continuous harassing raids impeded Park from properly executing the plan. A respite was needed to give the pilots time to practice the new procedures. What no one knew at that moment was that a single man would partly trigger the conditions that same day to bring about the much-needed lull.

As the Ju88s pummeled Takali and headed out to sea, they were harried by 126 Squadron while eight Spitfires from 249 Squadron besieging the escort of two dozen Me109s and at least 13 Macchis.

“We slammed up the hill to 25,000 feet where the fighters were covering the bombers,” said George Beurling. “The Ju’s were just going to work on Takali when we came along and they plastered the joint, leaving the drome pocked with bomb craters.”

Beurling’s eye fixed on four Macchis running in line astern formation. The Macchis saw Beurling and other RAF pilots coming and broke into two and threes. Beurling maintained his eye on the aircraft in the Number Four position. This aircraft happened to be flown by Sgt. Falerio Gelli of the 378th Squadron, who pulled into a tight, climbing turn. Beurling quickly fired a near perfect deflection shot. His cannons jammed, but the fire from his twin Browning machineguns tore into Gelli’s engine and radiator.

The Macchi flicked over into a spin and plummeted like a rock. Gelli pulled out at the last minute. His nerves badly shaken, he turned to make a run for it when his engine began discharging thick, black smoke. Too low to bail out, he looked for a place to crash-land. A church steeple loomed ahead. The pit of his stomach fell away. He turned the stick violently to evade the steeple and saw a tract of stony ground ahead. He crash-landed on the field, hitting his head hard on the control panel. He pulled himself free of the machine and walked to a safe distance before sitting down. He had crashed on Malta’s Gozo island. Maltese civilians found him with his head swollen by a great bump on his head. They did not lynch him.

The fracas continued in the sky overhead as Spitfires from 126 Squadron conducted head-on attacks on fighters and bombers. Meanwhile, Spitfires of No 249 Squadron came in from 10 o’clock. In the air was the great Captain Furio Niclot Doglio of the 151st Squadron, by now renowned within the Regia Aeronautica as a “Spitfire killer.”

Doglio had downed six Spitfires in eighteen combat missions, including two on 13 July. He was also known “The Savior,” when, days before, he had fought off a Spitfire which had been attacking a Ju88, for which the grateful German pilot had followed him back to his airfield to give him a bear hug. To his pilots, Doglio looked like one of those men who would get through the war unscathed. They were wrong.

As Doglio prepared to chase after 126 Squadron. His wingman, Sgt. Ennio Tarantola, wagged his wings to warn him about an incoming Spitfire on the left (the Italian radios were non-operational). Doglio understood and attempted to warn others members of the flight by also wagging his wings. It would prove a stupid, costly mistake. Beurling was flying the Spitfire.

There was a brrr of gunfire and a bright flash erupted through the air as Doglio’s Macchi blew up. Amid the flames and a great cloud of debris, a large piece of the Macchi could be seen falling towards the sea. It was the cockpit, with Doglio trapped inside. A frantic figure could be seen hammering at the canopy before the wreckage hit the sea.

Beurling lined up on a third Macchi, but when he spotted two Me109s below him, he decided they were better prey. He did a half-roll and came up underneath them, raking one in the belly with gunfire. Its fuel tank exploded and the Me109 went down. Yawing, Beurling let the second German have it, blasting pieces from his wing and tail. The horrified German sped for home, “skidding all over the sky.” His guns running dry, Beurling returned to Takali to refuel and rearm.

Doglio’s death devastated the Italians. “When he died, some of the fighting spirit of the Regia Aeronautica died with him,” said a member of his squadron, Lt. Ronaldo Scaroni. “There was a feeling that if Furio Niclot couldn’t survive, none of us could. For the first time we began to doubt that Malta could be taken.” Suddenly, Malta seemed invincible.

When Beurling submitted his combat claims to the debriefing officer, explaining that he had hit his first target (Gelli) in the port aileron and on the starboard side of its fuselage, squadron pilots and ground crews travelled to Gozo to inspect Gelli’s pancaked aircraft – where they found damage to its starboard fuselage and port aileron. This confirmation cemented Beurling’s reputation as a “crack shot.”

“He immediately became a hero,” said Lord Douglas-Hamilton.

No sooner had the Spitfires refueled and rearmed when a second call for scramble came in. Beurling and three pilots, including a fellow Canadian “Willie the Kid” Williams, took off again, racing for altitude. Their quarry was a single Ju88 and 20 Messerschmitts. Spitfires from 126, 185 and 603 Squadrons had already shot down four other Ju88s in the formation as they reached the coastline. White parachutes dotted the blue sky.

The quartet from 249 saw a great swirl of Germans circling the descending parachutes of their countrymen, ostensibly to protect them from harm. “Willie the Kid” Williams and Sgt. Red Bryden bounced the topmost Messerschmitts only to have Williams bounced in turn by Lt. Karl-Heinz Preu of Stab/JG53. Beurling launched in a desperate bid to save Williams’ life. As he interposed himself between the Germans and Williams, the Messerschmitts abandoned their attack on Williams and turned on Beurling.

A raucous, sweeping dogfight began. The combatants went round and round, performing loops, turns, split-Ss, and dives until Preu’s Messerschmitt entered Beurling’s gunsight. A single, one-second burst was all it took. The rounds tore into Preu’s glycol tank. His Messerschmitt turned over and dove into the sea from a thousand feet. Thus ended the life of Karl-Heinz Preu, an ace with five Spitfire victories. It was Beurling’s fourth victory of the day but he was not yet done. He peppered a second Messerschmitt, causing black, oily smoke to issue from its engine before the German fled for home.

Although only awarded a “damaged” for the last Messerschmitt, Beurling’s haul of four confirmed victories equaled an erroneous similar score awarded to Johnny Plagis in April, and left him at the top of the island food chain with 14 confirmed victories. He was now the island’s undisputed top ace — a position he would never relinquish.

Parachutes were dropping everywhere. Highlight of the day was ‘Screwball’ Beurling… he’s a wizard.

Noel Pashen, New Zealander, 27 July

Meantime, two more Me109s went down. One was flown by the great East Prussian ace, OberLt. Siegfried Freytag, of Danzig and I/JG77 who had 62 confirmed victories scored from over England, Russia and Crete. Freytag bailed out and landed in the water off Grand Harbor, in full view of observers. The British sent out a launch to get him but a German Do24 flying-boat set down and literally whisked Freytag from a life of captivity.

A last raid at 8 PM cost the Axis four more Ju88s and eleven fighters. Doglio’s death, low-serviceability rates and compressibility problems with the Macchi MC202 prompt the Italians to suspend their “Blitz.” It was the respite Park has been waiting for.

The edict banning pilots from visiting prisoners did not apply to Beurling, the man of the hour. He accompanied an intelligence officer to Gozo to question the captured Sgt. Gelli, who gave his name as Cino Valentini.

“Cino” was talkative but Beurling ruffled his feathers by declaring that Italian air tactics “stunk.”

“Cino” for his part, gave the impression that it was just poor dumb luck that he had been shot down— after all he was “a real pilot” with three Spitfires to his credit. He did not ask Beurling how many planes he had shot down. “Cino” also also told the British Intelligence officer that Italy would not lose the war, prompting Beurling to comment: “He sure thinks old Muss-face has done plenty for Italy, huh? I wonder how he feels since” the British are rolling up Rommel.

And Rommel was indeed being rolled up. Once the initial panic in the Egypt had subsided, the British 8th Army had made its last stand at a lonely desert railhead called El Alamein. By when Beurling was talking to “Cino,” what was known as the First Battle of El Alamein had come to a close after 27 days of relentless combat. British and Commonwealth troops under General Claude Auchinleck had fought Rommel to a standstill, preventing him moving from deeper into Egypt. A thwarted Rommel had dug-in east of Alamein, making repeated demands for reinforcements and supplies so that he could make another push in September. Depressed by failure and obsessed with supplies, he blamed Rome for his lack of success, railing against Italian corruption, Italian lethargy, apathy, bureaucracy and temerity.

Conditions were anything but ideal for the Axis over the Mediterranean. Park mounted long-range patrols with Bristol Beaufighters to interdict Axis planes flying from Italy to Libya while Beauforts attempted to harass all convoys plying the waves.

But Park was running out of time and he knew it. Fuel was being consumed at an unsustainable rate. At the end of July 1942, Malta’s fuel reserves stood at 4,000 tons, of which Simpson’s submarines alone consumed 50 tons per patrol each. The Chief of Staff of the RAF, Sir Charles Portal, suggested evacuating all aviation units on the island except for the Spitfire squadrons. But this would interrupt the vital need to interdict Axis shipping.

Finally, on 30 July, the Chiefs of Staff in London agreed to allow only the transit of Beaufort anti-shipping aircraft through Malta. They also ordered that “strikes from Malta must be reduced to an absolute minimum.”

The food situation was also dire. The failure of Harpoon–Vigorous had left Malta in crisis. The daily allowance for women and children was down to 1,000 calories. The infant mortality rate was one in three and the daily allowance for adult males was 1,100 calories — at a time when people in Britain never had to make do with less than 2,800 calories per day.

But deliverance was close at hand. The Admiralty had decided to mount a massive convoy to redress the odds. It was to be the largest re-supply attempt to date, with 52 merchantmen and warships. The convoy became a frame upon which the fate of Malta hinged. It was imperative that the ships reach Malta by 15 August, for that was the day when the island’s last reserves of food were scheduled to be issued to the Victory Kitchens.

Crossing this threshold would lead the government to its last option — the slaughtering of every horse and goat on the island, but which meat would feed the island for only five to ten days. After this, the island faced the certainty of mass starvation. The risks were high and the expectations immense.

1942. A Pedestal

In this period of upheaval, a large convoy gathered on the River Clyde in Scotland in the last week of July. The convoy, codenamed WS21S or “Pedestal,” was a repeat of “Harpoon,” but on a grander scale with 14 large and fast merchantmen (all of them 7,000 tons displacement or above) carrying food, fuel and ammunition.

Their escort consisted of scores of destroyers, cruisers and an unprecedented three aircraft carriers which was emblematic of the Admiralty’s newfound respect for these vessels, plus two powerful battleships which had been freed from duties in the Indian Ocean owing to the Japanese defeat at the Battle of Midway.

If British carrier operations had reached a surprising maturity during “Harpoon,” with carriers properly employed to run a convoy through enemy airspace, the new operation reflected the Admiralty’s belief that “sea and air power must be used in conjunction” if the convoy was to get through.

“Ships alone are now unable to maintain command at sea,” they declared. But a brainstorm from the Sea Lords this is not. Rather, it was the result of British naval officers having closely observed the workings of US carrier task forces in the Pacific.

Abruptly, the Fleet Air Arm, with years maligned as a shadow force, found itself being venerated. “It had taken nearly three years of war for the Royal Navy to find out how to use aircraft carriers,” quipped one naval aviator. He might have added: Better late than never.

The carriers, which were part of Vice-Admiral Sir Neville Syfret’s Force Z, are granted a grace period of three weeks to coalesce as a task force. No one had any experience in operating three carriers at once, with its complexity of air operations and procedures. Even “Harpoon,” with its two-carrier escort, had a peak naval strength of only eighteen fighters. Pedestal had 74.

Eighteen Fulmars, six Hurricanes and 14 Albacores were deployed aboard Victorious; six Martlets (US-made Grumman F-4 Wildcats) were on Indomitable as were 24 Hurricanes and 12 Albacores. The Eagle deployed 16Hurricanes.

All of the fighters were obsolete by the standards of aircraft employed by Axis land-based forces and worse, several squadrons were green. Two squadrons, however, were full of killers and budding aces. One was 800 Squadron, one of the Fleet Air Arm’s oldest flying units. This squadron had seen repeated combat since 1940 and was helmed by Lt-Commander Bill Bruen, a legendary naval aviator. The second was 880 Squadron under Lt-Commander Butch Judd, a bear of a man with a formidable temper whose grizzled, jet black beard gave him a piratical bent.

One of Judd’s deputies was Lt. Richard John “Dickie” Cork DFC, who, unusually for a naval aviator, had served with the RAF during the Battle of Britain in 1940. During that period, he had shot down five German aircraft. The Navy regarded him so highly highly that he had his own “private” Sea Hurricane.

Fleet Air Arm squadrons which participated in Operation Pedestal

| Squadron | Strength | Commanding Officer | Squadron experience |

| HMS Victorious | |||

| 809 Squadron | 14 Fulmars | Capt. Ronnie Hay DSC (RM) | Inexperienced |

| 884 Squadron | 6 Fulmars | Lt-Cdr. Buster Hallet | Inexperienced |

| 885 Squadron | 6 Sea Hurricanes | Lt. Rodney Carver DSC | New and inexperienced |

| 817 Squadron | 2 Albacores | Lt-Cdr. N.R. Corbet-Milward | Inexperienced |

| 832 Squadron | 12 Albacores | Lt-Cdr. W.J. Lucas | Average experience |

| HMS Indomitable | |||

| 800 Squadron | 12 Sea Hurricanes | Lt-Cdr. Bill Bruen DSC | Experienced |

| 806 Squadron | 8 Martlet IIs | Lt. R.L. “Sloppy” Johnston | Many new pilots |

| 880 Squadron | 12 Sea Hurricanes | Lt-Cdr. F. “Butch” Judd | Experienced |

| 827 Squadron | 16 Albacores | Lt-Cdr. D.K. Buchanon-Dunlop | Experienced |

| HMS Eagle | |||

| 801 Squadron | 12 Sea Hurricanes | Lt-Cdr. Rupert Brabner, MP | Experienced |

| 813 Squadron | 4 Sea Hurricanes | Lt. King-Joyce | Experienced |

| HMS Furious | |||

| 822 Squadron | 4 Albacores | Lt. H.A.L. Tibbetts | Average experience |

| Op Bellows | 32 Spitfire Mk V | For Malta | |

Each of the three carriers were to operate independently within the destroyer screen and to the rear of the convoy. Each was given a personal escort of an anti-aircraft cruiser. Victorious got HMS Sirius, Indomitable got HMS Phoebe and Eagle got HMS Charybdis.

Victorious, with her large contingent of slow-climbing Fulmars, was in-charge of low-altitude defense. Indomitable and Eagle were tasked with high cover. The five Hurricane squadrons were to protect the fleet from 20,000 ft. Two Fulmar squadrons had orders to fly at 5,000 ft, and the single squadron of Martlets was to be used at medium altitude. Eighteen fighters were to be on patrol at all times, with another 18 on constant readiness and 12 on immediate reserve. The experience of “Harpoon” had shown that at least two fighter-direction ships (to coordinate with Maltese air cover) were needed in case one was lost.

Consequently, Burrough’s Force X was granted two Air Defense Ships, Nigeria and Cairo. RAF officers were also embarked on command cruisers to coordinate RAF-Royal Naval activities. Once the convoy reached within 125 miles of Malta, Park’s squadrons were to assume air defense over the ships.

The merchantmen were a diverse group. The most vital of them was the tanker, Ohio, of the Texaco Oil Company. At Roosevelt’s behest, she had been transferred to the British register much to the angst and ire of her American crew. In recompense, the British had offered the Americans their merchant ship, the Glengyle which had been refitted as an infantry assault ship.

A gang of British seamen, bolstered by two dozen ack-ack gunners and a naval liaison officer moved aboard Ohio at Clyde. Their role was to assist with the complicated maneuvering of the vessel. The ship itself was given an English skipper, Captain Dudley Mason of the Eagle Oil and Shipping Company.

The ship metamorphosed into a strange creature of war, bristling with anti-aircraft weaponry, festooned with water-carrying pipes and fire-fighting equipment.

Two other American ships, the Santa Eliza of New York and the Almeria Lykes from New Orleans were manned by American seamen but carried large numbers of British anti-aircraft gunners. This created some friction because the Lykes crew expressed anti-British sentiments. The rest of the merchant crew were the pick of the litter from the British merchant fleet with convoy commodore A.G. Venables, a retired Royal Navy Commander, having hoisted his flag aboard Port Chalmers of the Port Line Limited Company of London.

All of the merchant ships were outfitted with anti-aircraft weaponry, plus parvanes to deal with mines and fire-fighting gear. The ships were loaded with mixed cargo to mitigate the impact of losses. Every available space onboard the ships was packed with crates, cartons and packages. There was barely space for the crews to move. The cargos totaled 105,000 tons, composed primarily of tinned food, alcohol, flour, ammunition and shells, and petrol, in addition to Ohio’s 11,500 tons of kerosene and diesel oil.

Syfret’s Force Z was to travel as far as Skerki bank and the Sicilian narrows, while Rear-Admiral H M Burrough’s Force X was to escort the merchant ships right to the island. Even the smallest of Syfret’s ships were more powerful than Burrough’s ships, with veteran L-class and Tribal-class fleet destroyers screening capital ships and aircraft carriers.

Burrough had several fleet destroyers, but his force was smaller and more vulnerable. A fourth aircraft carrier, the Furious, joined the fleet at Gibraltar, but her role was ancillary as she was charged with dispatching 38 Spitfires to Malta as part of Operation “Bellows”.

By the nightfall on 8 August, “Pedestal” was breathing upon the Pillars of Hercules. Like creatures of the night they venture into “the Rock” under the cover of darkness to refuel on the concurrent nights of 8/9 August and 9/10 August. This caused havoc at the harbor with a long queue of ships waiting to have their innards filled, or as in some cases, re-filled because of wholesale incompetence. Amidst the ongoing confusion, the crew of the Santa Eliza, listening to an enemy radio program, heard their ship mentioned by name along with the rest of the convoy.

A Vichy French airliner spotted Pedestal as it weaved a route towards Malta on the evening of the 10th.

The sheer scale of the convoy prompted Kesselring to fear an invasion of Sardinia or even Crete. The Italians took steps to reinforce their combat squadrons, assembling, through great difficulty, 500 aircraft to attack convoy.

At Sardinia they even prepared two experimental, explosives-filled SM79 drones to crash into the ships. The Germans contributed another 164 Ju88s in seven kampfgruppen on Sicily, 26 Stukas, 10 He111s bombers, 43 Me109s, eight Me110 heavy-fighters and four Do24 flying boats. Many of the aircraft had been hastily moved from airfields in Cyrenaica, where Rommel complained about their departure. Kesselring assured him that the transfers were temporary.

Axis submarines and aircraft homed in towards the convoy. On the following morning, 11 August, a German U-boat, U-73, torpedoed the Eagle. To the shock of the British, the great carrier went under in eight minutes.

Some 927 of the crew, including the skipper, Captain Mackintosh, were saved by nearby British vessels, but 233 men are lost. Only four of Eagle’s fighters had escaped the debacle. They set down on Indomitable and Victorious. In just a few minutes, the convoy had lost 25 percent of its fighter strength. Four minutes after her slipped underwater, the ship’s boilers exploded, reverberating U73 with a series of fearsome concussive blasts, each of which felt to the survivors on the surface like a hit across the back by a bat.

News of her destruction sent Churchill, who happened to be visiting Stalin in Moscow, into paroxysms of depression. His angst was partly displaced by anger at how badly everything was going. When Stalin said that the British withdrawal from Libya was evidence of British cowardice and if the British tried fighting, they might like it, Churchill launched into an inflamed defense of British military prowess. But he had not a single, recent victory to hold up the Soviets. Even the fate of Pedestal was in doubt, beset as it was by massive air attacks which British carrier aircraft are hard-pressed to repel. In the meantime, the captain of the U-73, Lt. Helmut Rosenbaum, was awarded an immediate Knight’s Cross.

“Operate with no other thought in mind than the destruction of the British convoy,” radioed Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring to Kesselring. As dawn came on 12 August, the British carrier aircraft prepared for the massive air battle they had been told to expect.

At 9.15 AM, an air patrol of eight Sea Hurricanes from 800 and 880 Squadrons reported 24 incoming Ju88s, all from Lehrgeschwader 1. The Germans lost seven Ju88s destroyed but return home convinced that they had somehow sunk a carrier and two merchant vessels.

A massive force 96 Italian aircraft appeared in front of the fleet at 12.15 PM, accompanied by the long-expected fighter escorts — 14 MC202s and 26 Re2001s.

Within the swarm were ten SM84s of the 38th Bomber Group armed with a revolutionary new weapon: the Motobomba FF (Mad bomb). Once dropped by parachute ahead of an incoming convoy, the 360-kg bomb was designed to submerge to ten feet where a gyroscopic motor caused it to circle underwater with a five-mile radius, without leaving a wake. The idea was that ships would blunder into one of these circling bombs. If no contact was made, the bomb was programed to explode after a pre-determined time. Each of the ten SM84s carried two of these bombs.

Despite a determined defense by the British and almost eighteen fighters, the attackers broke through with SM79s racing through on both sides of the fleet. In the face of awesome anti-aircraft fire, several Italian planes dropped their torpedoes at the big ships, losing three of their number, and prompting battleships Rodney and Nelson to alter course to avoid being hit. Meantime, bombers of the 38th Group had released their motobombas ahead of the convoy before being set upon by British Fulmars from 884 Squadron. Three of the bombers were shot down and the fourth fled for home on fire. Seeing the strange bombs descending on parachutes was enough to cause the fleet to alter course with a 45° turn to port.

The Italian attacks petered out by 1 PM without having achieved anything. As the Italians departed, fresh waves of German Ju88s arrived. Their arrival came at an opportune moment when there were mostly only Fulmars airborne to challenge them. The Hurricanes and Martlets were back on-deck, refueling and rearming.

A stick of bombs fell upon the freighter Deucalion. She grounded to a halt as her electrical power shorted out. To the horror of her crew, she began to settle in the water. Her skipper, Captain Ramsay Brown, ordered lifeboats be lowered as a precaution. Several British crewmen who had temporarily replaced his Chinese regulars, used this opportunity to jump ship.

At about this time, a bewildering aircraft was seen in the sky, flying in a straight line and but making no move to attack the convoy. Observers identified it as an Italian SM79. The Italians knew it to be one of their radio-controlled drones, packed with 1,000-kgs of explosives. The intention was to crash it into a carrier. Instead, the aircraft failed to respond to controls, much to the chagrin to its inventor, General Ferdinando Raffaelli, who was watching from a nearby Cant Z1007bis. His creation sailed insouciantly over the convoy. It later plunged into the slopes of Mount Khenchela, in Algeria.

Meantime, 880 Squadron, led by Judd, was vectored to a small formation of torpedo-armed Heinkel He111 bombers flying at wave-top height at 2 PM. Judd mounted a tail attack on a Heinkel, only to take heavy fire. With a bone-jarring crack, the starboard wing of his Sea Hurricane snapped off. His fighter tore into the water from an altitude of 500 feet. The irrepressible Butch Judd was killed.

By 5 pm on 1 August, the convoy was at Skerki Banks. The British carriers began picking up blips on their radar screens. Syfert scrambled a high portion of his operational fighters and at 6.35 PM the largest enemy raid yet came into view.

Syfret believed the attackers numbered as many as 200 aircraft. In reality, they numbered nine Italian Stukas, 29 German Stukas and 14 SM79 torpedo-bombers escorted by four Messerschmitts and 28 MC202s. Ordinary Seaman Roland Hindmarsh on the light cruiser Manchester remembered a palpable feeling of awe among his fellow sailors at the sight of the incoming force. Such numbers may be commonplace over Malta, but not at sea.

Many of the gun crews were exhausted, having been on readiness for nearly forty-eight hours. As Hindmarsh and the other gunners at ‘A’ Turret swung their guns into position, a midshipman on duty calls that the Stukas are diving.

The Manchester began to shake violently as her entire compliment of anti-aircraft batteries opened fire, showering the blue sky with long, swaying lines of glinting, glowing metal. “Train right,” someone called and released each battery to independently engage targets. “Low elevation, short fuse,” called the midshipman. “Target nine torpedo bombers, sea level!”

The guns swung low and opened fire. The water began to froth. The SM79s continue their run-in even as Manchester turned violently to starboard to avoid an incoming torpedo. Abruptly, the torpedo bombers veered off and the guns fell silent. A faint cheer broke out along the turret crews. Manchester had survived, but the ordeal of Indomitable was just beginning.

Overhead, 29 Fleet Air Arm fighters were entangled in a deathmatch with Axis aircraft. Captain Ronnie Hay’s 809 Squadron shot down a Savoia-Marchetti SM79 torpedo-bomber before he and his squadron were jumped by Messerschmitts and Macchis. Gunfire pummeled a Fulmar which fell in flames. A second was hit in the wings, prompting the other five to dive for the deck to escape.

Lt. Dickie Cork and Blue Section of 880 Squadron hurled themselves into the midst of Axis fighters trying to attack the Fulmars, but Cork was distracted by a SM79 flying low towards the fleet. Moving into attack position, he hammered it repeatedly until he could see fire sprouting from its innards. A crewman bailed out as the aircraft soared above the water at 50 feet. The bomber slammed into the sea seconds later, followed by the crewman. It was Cork’s third confirmed kill of the day, having dispatched a Me110 and a Ju88 earlier. Then he committed a rookie mistake. He decided that he wanted to photograph surviving members of the Italian crew in the water with their little dinghy.

Two Italian Macchis fighters poured fire into his Hurricane. Cork escaped by diving towards the sea but his fighter was too badly damaged to reach indomitable. He set down on nearby Victorious, his engine seizing just as his arrestor hook caught on the line. The Hurricane was assessed as being beyond repair and dumped over the side.

Fifteen minutes after the start of the raid, as Syfret’s fighter reserve (a section of Hurricanes from Indomitable) prepared to launch, a dozen German Stukas from I/StG3 dove out of the hazy, smoke-filled sky. Three bombs plunged into the carrier. “All we saw of her for minutes was columns of spray,” said Nelson’s executive officer. “Finally the maelstrom subsided and there was ‘Indom,’ still there, but blazing both for’ard and aft of the island, with great columns of smoke pouring from her flight deck.”

A bomb had penetrated her deck armor behind the main deck lift, twisting it out of shape, making it impossible to bring up aircraft from the hanger below. A second bomb had exploded in the mouth of the hanger killing and maiming many of the maintenance crews working there and ramming the already buckled seven-ton aircraft lift, which was at full elevation, up on its chains, two feet above the deck. This prevented the aircraft from landing.

Fires raged throughout the ship even as it took on water. The fires were so intense that a crewman on another ship believed that the “flight deck was dripping molten metal.” This was ignited aviation fuel.

Only the sheer determination of damage control parties kept Indomitable afloat, and by 7.30 PM, making 28½ knots, she raced to rejoin the convoy. The Germans returned home to make the incredible claim that they had set the USS Wasp on fire with six bombs (the Wasp was actually off Guadalcanal in the South Pacific). Fifty men had died aboard Indomitable and another 57 were wounded (the majority of the casualties from 827 Squadron). The damage to her flight deck was enough to prevent her from launching or receiving aircraft — leaving her airborne fighters in the lurch.

These aircraft diverted to Victorious, but that carrier was already crowded and the arrival of 12 of Indomitable’s fighters between 6.30 and 7.30 PM caused pandemonium as deck crews desperately bundled the new arrivals under fire into jam-packed hangers.

Overhead, a new wave of enemy aircraft appeared as the previous wave circled overhead and went home. An aerial torpedo plunged into the destroyer Foresight, tearing her stern to pieces and sending men “flying spread-eagled through the air,” according to a gunner aboard the Almeira Lykes. With her back broken and her propeller shafts fragmented, the destroyer was as good as finished. The destroyer Tartar took her in tow, but the continued threat of aircraft and submarines prompts her scuttling on the following day.

It is almost 6.30 PM before the last of the attackers disengaged – 45 minutes before Syfret was to pull back Force Z to Gibraltar. By now, Victorious was overflowing with aircraft. The Fulmars and Martlets were sent down to the hangers, but the Hurricanes were unable to fold their wings and unable to use the lifts. Many were dumped over the side. By the end of the carnage, Victorious only had 10 Fulmars, eight Sea Hurricanes and three Martlets ready for combat. She had started out the day with 50 fighters.

At 6.55 PM, Syfret received firm orders to pull back to Gibraltar. As the carriers and the other heavyweights turned away and vanished over the horizon, the merchantmen grimly contemplated their fate. The presence of the carriers had not mitigated their ordeal. Now in their absence, hardly a man was left in doubt that the worst was yet to come.

Syfret hoped for the best. So far, not a single cargo ship had been sunk and in two days of combat, his carrier-borne fighters had claimed the destruction of 39 aircraft, with Indomitable alone claiming 28 aircraft shot down on the 12th.

Syfret’s misplaced hopes that the convoy, having reached the Skerki banks, would be immune from further submarine attacks was shattered at 7.55 PM, when under a still bright Mediterranean sky, the Italian submarine Axum under Lt. Renato Ferrini fired four a salvo of four torpedoes at Burrough’s heavyweights, Nigeria and Cairo.

The first torpedo tore into Nigeria sixty seconds later, flooding her forward boiler-rooms, cutting off her engine power and jamming her rudder. Two torpedoes hit Cairo, blowing off her stern and the fourth hit the Ohio, blasting a 20-foot-wide hole in her side, below the water line. Ohio shuddered to a stop, flames roaring in her kerosene tanks and licking at her side, her boilers doused, forcing a trailing freighter, Empire Hope, to take drastic evasive action to avoid a collision.

The convoy became confused, with Burrough on Nigeria being temporarily unable to communicate with the rest of the ships. In his silence, the convoy lost all sense of cohesion. Some of the ships turned around to formate with Nigeria, which because of her jammed rudder, sailed in circles. Others proceed eastwards and become separated from the main force.

It was only at 8.15 PM when Captain Onslow of the destroyer Ashanti chased down the circling Nigeria and matched her speed – to allow Burrough to transfer his flag to the destroyer – that the first step to reclaiming control was made.

Cairo lay pitifully in the water, her stern in the sea. Burrough ordered her evacuated and sunk. Three torpedoes from the destroyer Pathfinder fail to explode on impact — much to her skipper’s embarrassment. Sustained gunfire from the destroyer Derwent finished the job. Next, when some semblance of control was restored on Nigeria, Burrough ordered her back to Gibraltar, accompanied by the destroyers Derwent, Bicester and Wilton, which were overburdened with Cairo’s 377-strong crew.

The loss of the two fighter control ships effectively deprived the convoy of its fighter control abilities and badly jarred the navy’s nerves to the extent that when several Beaufighters from No 248 Squadron arrived overhead, the aircrews heard an unusual signal being transmitted in the clear: “If it flies, shoot it!”

A moment later, the Beaufighters found themselves under siege from their own fleet. The aircraft peeled off and exited the area at high speed. This was unfortunate because minutes later, at 8.35 PM, just before sunset, the Germans launched a late attack on Force X with 37 bombers.

By this time, Ohio was back on the move, having relit her boilers and having extinguished the flames in the kerosene tanks. A bomb fell aside Ashanti, causing a boiler to eject flames outward, setting the destroyer partly on fire. Captain Onslow coolly moved alongside Ohio and signaled the tanker’s fire-fighting crew: “Put out, please.”

A loud explosion sounded nearby. A Heinkel He111 had scored a direct torpedo hit on the Brisbane Star, blowing a great hole in her side and flooding her No. 1 Hold. Losing speed but still able to make revolutions, her skipper, Captain Riley makes the decision to proceed to Malta alone. He turned towards Cape Bon, to “creep along the coast or adventure on.”

Nearby, the Empire Hope yawed and turned furiously, dodging 18 bombs, until the 19th exploded at her side, crippling her engines. A sitting duck, she attracted a horde of bombers and at 8.50 PM, took two direct hits which prompt her cargo of ammunition and fuel to erupt into flames. In the massive explosions that followed, dozens of men were hurled into the water with burns. The skipper, Captain Williams, ordered an immediate evacuation, but as the men paddled away in the lifeboats, they realized that the skipper and the chief engineer were still onboard. When the chief engineer appeared on deck for evacuation, he was in full uniform and declared that he had no intention of falling into enemy hands in his dirty, boiler-suit. He need not have worried. Nearly the entire crew was saved by the destroyer Penn.

Twelve minutes later, a torpedo from a Heinkel plowed into Clan Ferguson, igniting her cargo of 2,000 tons of aviation fuel and 1,500 tons of ammunition, and creating such an explosion that it seared observers on the nearby Glenorchy and Wairangi. Incredibly, 64 of her crew survived the conflagration but were captured by the Italian submarine Alagi and handed over to the Vichy French in Tunisia.

Meantime, Deucalion, accompanied by the destroyer Bramham, was quietly hugging the Tunisian coastline, working her way towards Malta when she was spotted by a pair of Ju88s. With their engines turned off, the Ju88s dove silently. The first bomber soared overhead without attacking and the second came to within 200 feet before turning on its engines. Every gun crew aboard the freighter lit up on the incoming Ju88, scoring hits. The Ju88 did not waver and as it drew level with the bridge, it dropped an object which appeared to be rocket-propelled. The projectile raced towards the ship horizontally, smashing into her with a thunderous roar which ignited aviation fuel and kerosene in the No. 6 tween-deck. Almost immediately, the tail of the ship erupted into an inferno.