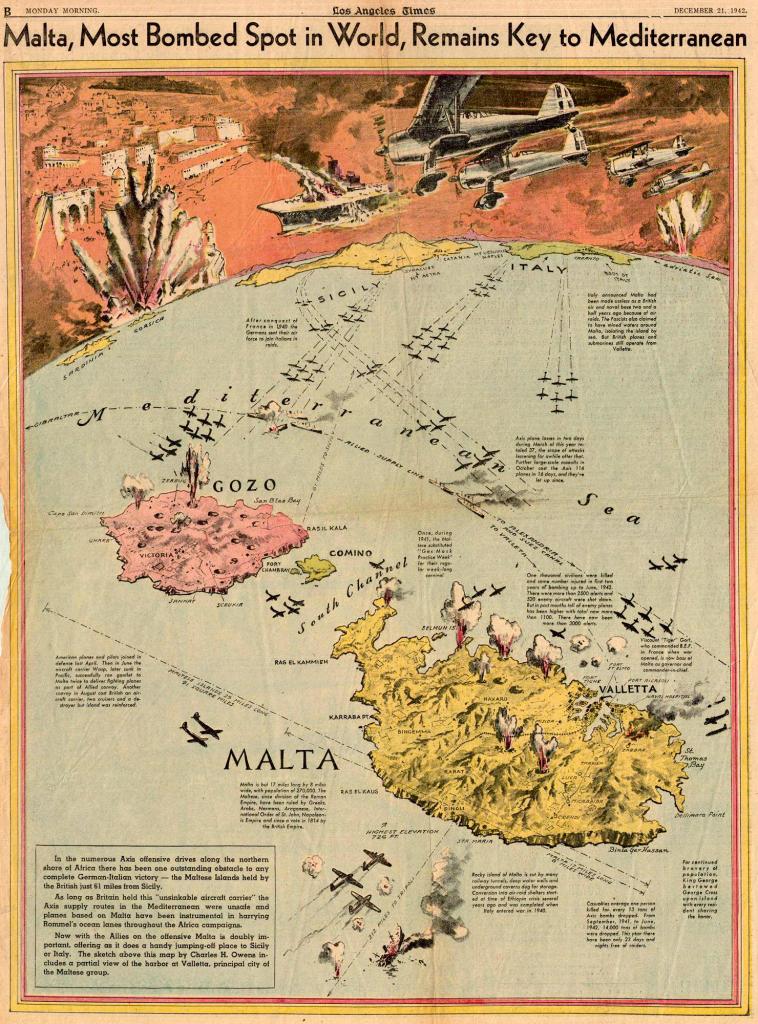

1942, The Storm

Unrelenting bad weather and a deluge of bombs made a mess out of Malta’s three airfields. Lloyd enlisted the army’s help to not only restore the airfields but to improve them. Through herculean effort, the troops worked 12-hour shifts for the next three months in searing sunlight and in lashing rain. They laid 27 miles of dispersal tracks, built 14 large bomber pens, 170 fighter pens, 70 reconnaissance aircraft pens and 31 naval aircraft pens, using nothing more than sand-filled gasoline cans and sandbags.

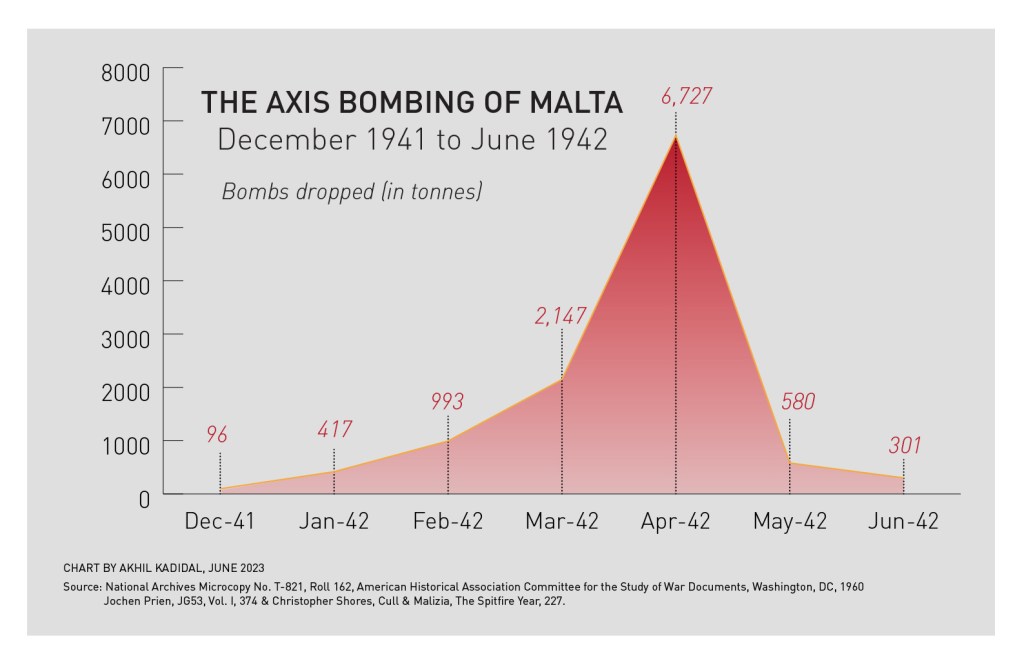

On 3 January, the Axis launched a mini-Blitz against the island to cover the passage of an Italian convoy, codenamed M43. With six freighters, the convoy carried a mass of tanks and artillery, plus 3,504-tons of military supplies for Rommel.

Already socked in by bad weather, Malta began to reel under the pressure of the initial Axis attacks. On that day, Pilot Officer Howard Coffin, a handsome, tall American from Los Angeles with slicked-back blonde hair and an immaculate sense of dress, was so intent on plugging an Axis bomber that he failed to notice two Messerschmitt Me109s on his tail. The aircraft were flown by Lt. Gerhard Michalski of 4/JG53 and his wingman.

“They used cannon shells and almost blew my ship out of the sky,” Coffin said. “I was hit in the arms and legs by shrapnel. Gas began pouring out of my tank.”

Coffin pancaked his aircraft at Takali. He remembered a wheel coming off his aircraft and veering off, bouncing along its own trajectory before his world went black. Coffin woke up 24 hours later at Mtarfa Hospital, woozy with morphine and unable to move any of his bandaged limbs.

When the doctor came in, Coffin gave him a look as if to say “what’s with the bandages?” He then exclaimed: “Got a date in Valletta!”

The safe arrival of convoy M43 on January 5 gave Rommel 54 tanks, 19 armored cars, 74 trucks and motor transports, dozens of anti-tank guns, artillery pieces. The delivery of four panzer companies with Panzer IIIs and IVs represented a serious setback for the British 8th Army defending Cyrenaica. But when the British sent a convoy of their own to Malta and deployed Wellington bombers to harass Axis sea lanes, the conversation in Axis circles once again turned to question of invasion.

Hitler remained recalcitrant. He argued for the continued “neutralization” of the island by air, while sending tanks to Rommel to help “recapture the operational initiative.” In the absence of any cogent policy towards Malta, the German Luftwaffe continued to bomb, shoot and kill over Malta, with no end in sight.

As the bad weather finally broke on January 13, the Luftwaffe emerged in strength, savaging the Maltese landscape in an imbroglio of flames, explosions and hot metal which the defending Hurricanes were nearly powerless to stop.

Most Hawker Hurricanes on the island were of the Mark IIB variant, armed with eight machineguns. These aircraft were useless against the German Ju88 bombers which are only marginally slower than the interceptors and were equipped with bulletproof glass and armor plating around the cockpit. “…A lot of our time was taken up by attempting to survive in well-used Hurricane Mk Is and later Mk IIs,” said one frustrated pilot, Sgt. Fred Etchells of 249 Squadron. “On several occasions…to my disgust, I saw an odd Ju88 unescorted and asking to be shot down, but even with all power on and the nose down by 15°, it was able to increase distance between us.”

Group Captain Basil Embry, a technical expert sent by the Air Ministry to assess the situation recommended revamping operational procedures and replacing the Hurricanes with Spitfires. Vice-Admiral Ford complained to Cunningham: “I’ve given up counting the number of raids we are getting. At the time of writing, 4 PM, we have had exactly seven bombing raids since 9 am, quite apart from over a month of all-night efforts… Something needs to be done at once.”

The island was hit by a hundred attacks and 1,800 tons of bombs that January— 800 tons of which had fallen on the airfields, destroying or badly damaging over 50 aircraft. British fortunes on Malta and the Mediterranean are at their nadir and two small convoys sent in January did little to alleviate Malta’s growing food crisis. This prompted Vice-Admiral Ralph Leatham (replacing Ford whose tour had expired) to calculate the island’s first “Target Date” — when the island was scheduled to run out of food and beyond which it will surrender to the Axis. Leatham’s first target date is set in mid-June.

An air battle on January 25 revealed a typical example of Allied air inferiority over Malta. Under orders to protect the departure of two merchantmen, the Glengyle and the Rowellan Castle which were returning to Alexandria, 15 Hurricanes patrolled over the ships that evening. The cargo ships were empty, barring some “40 women and children (service families)” who had been given temporary accommodations in the No 3 hold of Rowellan Castle.

Three Hurricanes from 249 Squadron aborted the patrol because of mechanical problems, including Pilot Officer Harry Moon of 249 Squadron whose engine failed. He was forced to glide back to the airfield to make a “dead-stick” landing, but the rest carried on. Initially, all was quiet, until the ships passed Delimara Point at the southeast of the island, when four Ju88s and a squadron of Me109s materialized out of thin air. Seven Hurricanes from Hal Far throttled up to attack the bombers when the Me109s led by Major Günther von Maltzahn (the commander of Jagdgeschwader 53) bounced eight Hurricanes from 126 and 249 which were tasked with top cover.

“I drew towards them from behind with my five aircraft,” said Major von Maltzahn. “Then coming at them from the rear from out of the sun in wide curves, I set up the first attack against…five Hurricanes…[I] attacked the Hurricane lying on the extreme left. She was hit, went down immediately and broke up into flames into the sea.”

The alarmed Hurricanes increased speed, turned back over land and attempt to out-climb the Messerschmitts. Maltzahn spotted two Hurricanes climbing behind him, presumably to get on his tail. Instead, the two planes flew out over Malta. Their lack of aggressiveness puzzled Maltzahn, but he ignored them and focused on a flight of Hurricanes ahead. He fixed the aircraft on the extreme left in his gunsight and opened fire. His shooting turned the Hurricane into a sieve. The pilot bailed out, hurtling up and over Maltzahn’s Messerschmitt before vanishing from view. Another Hurricane, minus its pilot who had bailed out, flew in rings upside down until it hit the ground.

Having shot down three Hurricanes and damaged one from the top flight, the Messerschmitts then caused havoc among the lower flight, shooting one down and seriously damaging four others. Parachutes blossomed over the island. When the Germans retired, it was as von Maltzahn said: “[a matter of] good luck that we came out of this combat completely unscathed, without a hit.” The overconfident Germans claimed eight Hurricanes shot down, with Maltzahn claiming two and his wingman, Lt. Franz Schieß (Schiess) of Austria, claiming one.

The engagement had been a disaster for the RAF. Several veterans pilots had been shot down, killed or wounded, including: Flight Lt. “Ozzie” Crossey who crash-landed, Pilot Officer John Russel who was killed, Pilot Officer C.A. Blackburn who bailed out wounded, Pilot Officer C.F. Slugget who bailed out unscathed, Flight Lt. “Professor” Thompson who landed wounded and Flying Officer Andy Anderson (nephew of the late, great WWI ace, Albert Ball) who bailed out wounded.

By the start of February, Malta was down to 28 operational Hurricane fighters. The Air Ministry belatedly informed Lloyd of its intention to equip his command with five squadrons of Spitfire. However, the Air Ministry did not give Lloyd a timetable for delivery

In the interim, the island aircraft remained at the mercy of the Messerschmitts, barely able to defend themselves much less protect Malta.

On February 7, the island registered 16 alerts over a 24-hour period — a new record, with the Maltese spending a staggering 13 hours under “alert” status. It was a worrying trend which Lloyd had no means to arrest.

A thousand tons of bombs would be dropped on the island in February as day-by-day, the Hurricane force and its pilots were depleted in an unending battle of attrition. The situation was so desperate that statistically of a flight which took off to intercept the enemy, roughly half returned, often to an airfield which was a smoldering ruin with burned-out aircraft lying on the tarmac. The submarines were similarly unspared.

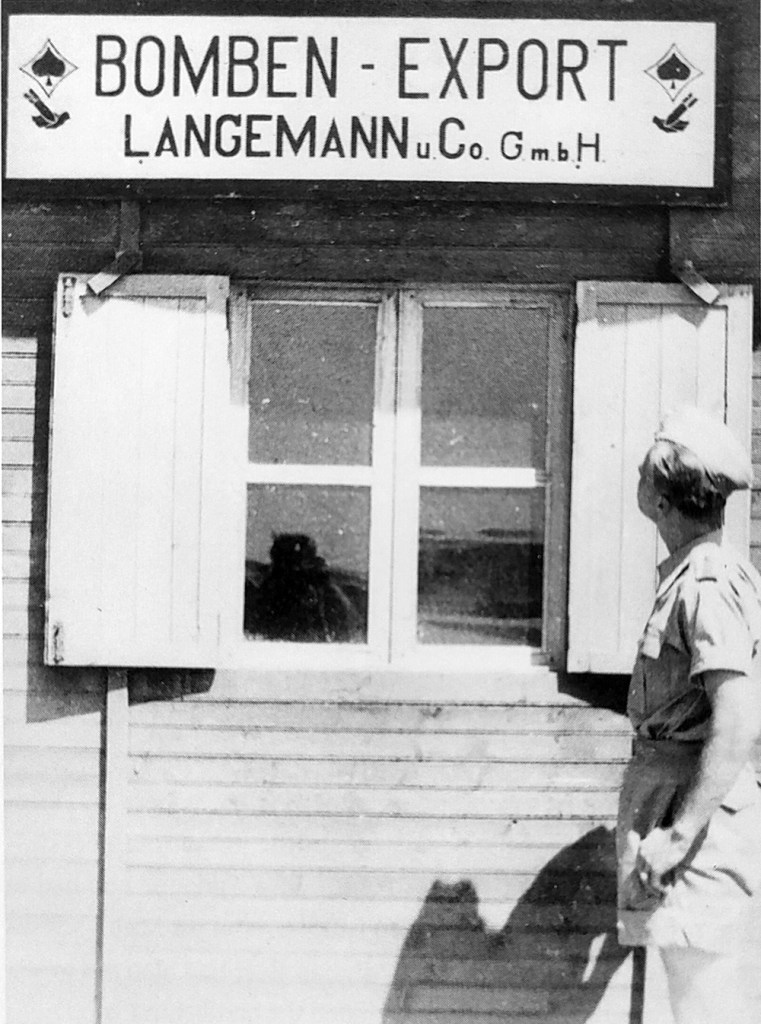

For nearly a year, the submariners could contend themselves that the Germans did not know where their base was located. A map found in a crashed German bomber in April 1941 had showed that the Germans believed the “U-boothausen” was located at Msida Creek, half a mile away. Simpson had issued orders that the base not advertise itself. The base flew no white ensign and all men in uniform had strict orders to stay out of sight during air raids.

But the Germans had corrected their intelligence error. On 6 February, the Germans subjected the dockyards and Manoel Island to a punishing airstrike.

With typical stoicism, submarine operations continue unabated, but the crew of a new arrival, the Tempest, a T-class submarine were ashen by the scenes of destruction which greeted them upon their advent on February 8.

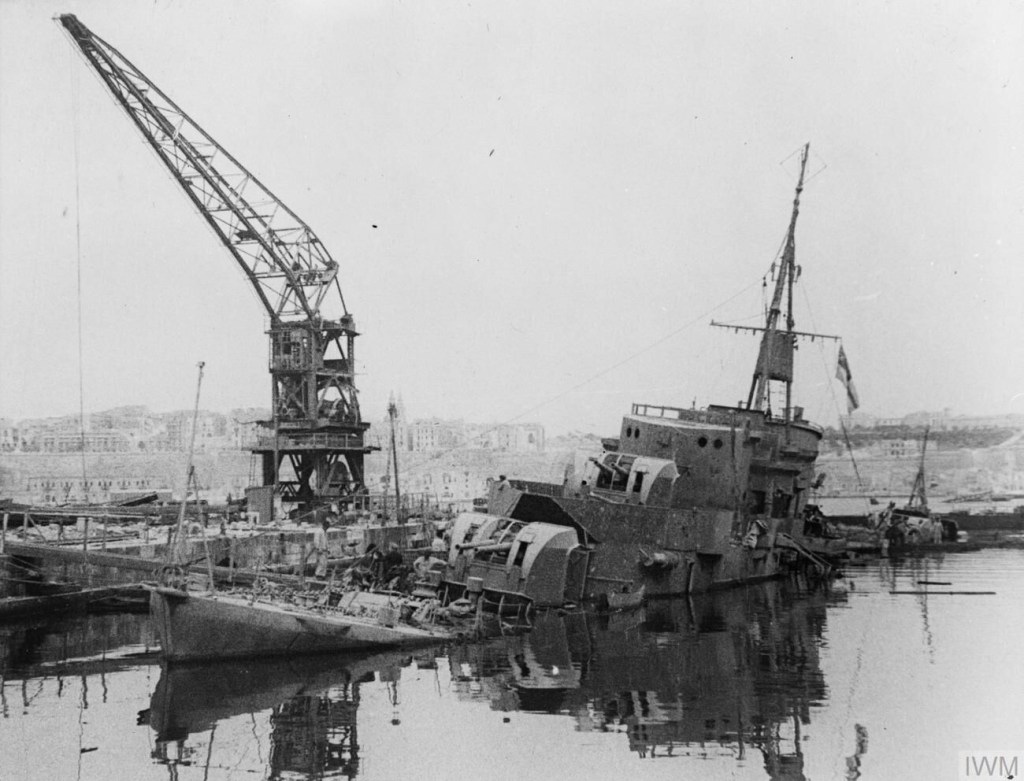

“The houses and high-piled palaces around Grand Harbor were in many places, piles of rubble now, and a film of honey-colored dust lay upon the sparkling blue of the harbor,” said Chief Petty Officer Charles Anscomb. “The docks were smashed and sunken ships blocked the creeks and the main harbor, waterlogged merchantmen sitting on the bottom, destroyers with their whole bows amputated or sunk in mid-stream with their empty crows’ nests watching a forlorn graveyard of fine vessels. It looked as if Malta was crumbling into the sea.”

As if this were not enough, one of Simpson’s submarine commanders, Lt Desmond S R Martin, compounded Malta’s travails.

When Simpson allowed the Una to embark on her second Mediterranean war patrol on 9 February, he believed he was sending off the boat with an able and experienced skipper in the form of Martin.

Martin had commanded the submarine from the day of her in inception in October 1941. “Martin…I knew and regarded as a sound chap,” Simpson said and it was on this personal feeling that he assigned Una to patrol the approaches to Taranto in that second week of February.

At about the same time, the Admiralty issued an order that the British government had given the 8,100-ton Italian tanker Lucania safe conduct. The tanker’s mission was to deliver fuel to the Italian liner Vulcania which was due to evacuate Italian refugees and civilians from an internment camp at Mombasa in British Kenya. The Admiralty order was passed to all submarines at sea, including Una. “She will not be zigzagging, will not be escorted and will be marked on both sides amidships with the Italian flag… [She] is not to be molested,” the Admiralty order said.

Consequently, at 10.10 AM on the 12th, when Lt Commander Edward Woodward of the submarine HMS Unbeaten spotted the tanker, and recognized her, he let her pass – as did Lt-Commander Napier “Bill” Cavaye of the HMS Tempest. But two hours later, Martin, by now ill with pneumonia, was summoned from his cabin and was told of smoke being sighted to the north. As the Una closed the distance, Martin saw a monoplane aircraft patrolling above the unidentified ship.

Without waiting, Martin launched three torpedoes from a range of 2,600 yards. One torpedo slammed into the Lucania dead-on, resulting in a catastrophic explosion. As the vessel went into her death throes, Martin was perturbed to notice that the ship had “indistinct markings.” When the noises of the explosion reached the Tempest, Cavaye was horrified to see the “untouchable” ship sinking beneath the waves.

The crew of the Lucania sent out a last SOS before the ship went under, as if they could not understand the reason for this British treachery. Even the British Admiralty was incredulous. That same evening, Simpson received a signal from London demanding to know if the Lucania had been sunk. A befuddled Simpson forwarded the message to Una. Martin responded that he had sunk an “unescorted tanker in the morning.” Alarmed, Simpson immediately recalled Una to Malta and assigned Cavaye to take over the patrol area.

Meantime, an angry Supermarina dispatched submarine-killing units to the area. Among them was a veteran submarine hunter, the Spica-class torpedo boat, the Circe. This vessel was made even more lethal by the addition of German S-Gerät (sonar). Under the command of its experienced skipper, Lt-Commander Stefanino Palmas, the Circe angrily thrashed the waters over the site of the now-departed Lucania. Initially the radar scope was clear, but Palmas being the shrewd hunter that he was, waited for darkness to come and for the British to make a mistake. The innocent Cavaye obliged by surfacing after nightfall.

Petty Officer Charles Anscombe, who was assigned as a lookout on the Tempest, went up top to take a lungful of “clean air and [gaze at] the cool blackness of the night.” The hours passed. Relieved of his duties three hours later, he went below for sleep. He slept soundly until wailing of the submarine’s siren jarred him awake. It was 3 AM.

Circe was plowing through the waves at top speed towards Tempest. Cavaye ordered an immediate crash-dive. As the submarine went under, the British heard the hypnotic pulsing of Circe’s engines overhead. The noise faded but returned as if the Circe was closing in on a homing beacon. Then the depth-charging began. “Being depth-charged is something which cannot be imagined,” Ascombe said. “It is a terror which has to be experienced.”

Cavaye ordered a depth of 150 feet, but a gentle rattling onboard the submarine grew to a crescendo of clattering dials, gauges and warping metal as the submarine’s depth gauges passed 150 and continued past 165. The submarine was out of control. Fighting the dive, Anscomb and second coxswain Burns leveled the submarine at 350 feet and brought her back up to 150 feet. When the submarine was stabilized, Cavaye decided to wait out Palmas. Long hours passed in silent apprehension. At 7 AM, just when it seemed as though they had given Circe the slip, the British heard the sound of retuning engines and the pinging of sonar.

At that moment, a shattering explosion occurred near the submarine. Tempest began to plummet again, this time towards depth of 500 feet, where the hulls of submarines are known to crack like egg-shells. Cavaye ordered the blowing of the main ballast tank to arrest the fall and the submarine rose, pitching and bowing all the way up. To prevent the submarine from breaking the surface, the crew flooded the tanks again — making tell-tale noises and discharging large air bubbles which betrayed their location.

The depth-charging began anew. Already, the Tempest was in shambles. Taken to the brink of implosion, she had lost nearly all of her main lights. The instruments in the control room had blown out and a propeller shaft had come disjointed in its housing. Her hydroplanes were warped and the hydrophones were no longer operable. Her bulkhead fixture began to crack and her operational instruments shattered. In the engine room, heavy spare parts weighing a ton and bags of mail destined for boats in Alexandria came lose and hurled about the place.

For three hours, the men of Tempest waited in this condition, about a hundred feet below the surface of the sea, waiting for the nightmare to end. In the fetid, cramped stillness of the bruised submarine, a crewman slinking through on an errand to repair electrical lines, accidentally kicked a bucket which clattered loudly across the deck.

“I’ll have that man shot!” Cavaye shouted.

Sea water jetted from small cracks in the hull and began to collect in the battery room, with its high content of sulphuric acid in battery compartments. This triggered the ultimate nightmare of submarine crews — poisonous chlorine gas. Cavaye decided to surrender. The crew donned their DSEA escape gear and as the Tempest began a slow ascent to the surface. Cavaye had ordered his crew to place demolition charges to scuttle her topside.

Circe saw the Tempest as she shot up onto the surface half a mile away. Palmas was in no mood for mercy. Closing in fast, he ordered his men to open up with their machineguns, hammering the submarine’s conning tower and killing some of the first men to leave the hatch. Others were shot and killed while in the water. The sea was so rough that when Anscomb reached the hatch he saw Circe’s masts disappearing and reappearing behind high waves. He avoided the machinegun fire and jumped into the water on the blind side of the submarine’s coning tower. He was later pulled aboard the Circe in a semi-unconscious state to join other survivors.

Palmas was anxious to tow the Tempest to Taranto like a proud fisherman with haul of a lifetime. But the submarine sank enroute with thirty of her the crew still onboard. It was the end of Tempest. Out of her 62-man crew, only three officers and 20 ratings had survived. Among the dead was Cavaye. Yet, even the sacrifice of Tempest was unable to satiate the Axis thirst for blood and on the next morning, war came to Grand Harbor with a fervor unseen since the “Illustrious Blitz” of January 1941. It was Friday the 13th.

German raiders enveloped Grand Harbor and Marsamxett Bay with great clusters of parachute bombs. Leading Seaman Jack Casemore of HMS Unbeaten happened to be walking towards the exposed causeway connecting the island to Sliema when the bombs began falling.

“There was some waste ground between the base and the little bridge on the Sliema front. The air raid sirens had already gone but I thought I could get ashore before they arrived,” he said . “I was halfway across this waste ground when the bombs started to fall. [The]… dive bombers…were targeting our base and submarines and as they were pulling out of their dive, they were machine gunning; first the bullets were in front of me and then they were just behind me. I was petrified; I was running backwards and forwards and eventually hid under a huge oil tank.”

Simpson, who had been near the base entrance gate when the klaxon sounded, ran to the nearest shelter which was adjacent to the mess deck. Inside was a large group of men. A stick of bombs fell on Pieta, a half-mile away, flattening the home of Maj-General Daniel Beak, the new army commander on Malta. The General was in a bathroom when the bomb struck. The sturdy lavatory walls saved his life.

Simpson could hear the wail of a Stuka overheard as it dove on Lazaretto. The bomb crashed nearby, shaking the entire building. Simpson left the shelter and sprinted into Lazaretto to “assess the damage.” He found three Engine Room Artificers (ERAs) and another man on the mess deck who had not made it to the shelter. The windows had blown in. Glass littered the floor. Their unfinished breakfast was coated with fine power and dollops of rocks. The men appeared to be in shock, but seeing Simpson they pulled themselves together and made their down below to the shelter.

During a second raid at 2.30 PM, the Germans dropped parachute bombs on Manoel. These hit the western end of Lazaretto, causing the roofs of two entire stories, solidly built with limestone, to come down on the men’s quarters located in that part of the building. Eight other parachute bombs fell in other parts of Manoel. At Valletta, a bomb hit the Governor’s palace, prompting Dobbie and his staff to evacuate their offices to San Anton’s Palace in Verdala. Furious ack-ack fire brought down a Stuka, but German casualties were light in comparison to the damage they had wreaked. The raids had been uncontested by the RAF which was grounded. This enraged not only the submariners and Maltese civilians but also the Messerschmitt pilots of JG53, who “vented their rage” on a picket-boat south of Malta, tearing it to pieces in six passes.

Beak installed a quartet of anti-aircraft guns around Lazaretto to handle future attacks, but these could do little against continued massed raids which upset life at the submarine base. Only the arrival of Una on the 16th temporarily diverted Simpson from his immediate problems.

On entering the harbor, Una signaled that the first lieutenant was in charge as the skipper was ill. Unfazed, Simpson went down into the submarine to confront Martin.

He found Martin in a state of anxiety. Martin feebly argued that tanker he had sunk could not have been Lucania because it was being escorted by an aircraft and did not have the proper markings on the side.

Simpson, however, learned that Martin had fired his torpedoes at the tanker from an angle of 30 degrees — at which angle the markings would not have been visible. Martin’s continued arguments infuriated Simpson. “I suppose [Martin] was willing to believe anything he wished to believe,” Simpson says later. “I felt that I had been deliberately insulted and disobeyed; also the constant bombing was not helping my temper.”

Martin’s number one, Lt. L.F.L. “Rocky” Hill, came to his chief’s defense by arguing that Martin had never even seen the Admiralty order before sinking Lucania. Simpson was unamused.

Simpson immediately relieved Martin of command and sent him home to explain to the Admiralty why he had disobeyed orders. When it was reported that Tempest has been destroyed as an unintended victim of Una’s carelessness, Simpson’s rage became engorged. He hoped that Martin would be arraigned before Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary, who was known to be livid over the Lucania’s destruction. Command of the Una was handed to another officer, Lt. Pat Norman.

In England, a board of inquiry stripped Martin of frontline command. He would return to active duty in November 1942. But his first command was shore-based. He was given command of HMS Ultimatum during that submarine’s refit. He was next given command of the submarine Seadog, but discovered that the Admiralty had lost faith in him. When finally given command of a T-class submarine Tuna in 1943, Martin saw it as a chance for redemption. With Tuna, he sank U644 in April 1943, and claimed a second U-boat destroyed a month later. These acts would win him the DSO and reform his reputation.

Meanwhile, Malta was gradually vanishing under a carpet of bombs. The Admiralty dispatched a new convoy codenamed MF5 to resupply the island. German aircraft swarmed the convoy and every freighter was sunk. Its destruction exacerbated shortages of all kinds on the island. Stocks of torpedoes become so reduced that the submarines of the 10th Flotilla were reduced to two apiece.

On Sunday, 15 February 15, the Germans kept the island on alert for a record 19 hours and 59 minutes. A series of running battles developed. A German bomber penetrated the RAF’s meager fighter shield and bombed Kingsway, Valletta’s main road. Several bombs hit the Regent Cinema House where a packed house was watching a Gary Cooper melodrama. Scores died, but one sailor found himself trapped in the cinema’s bar. He sustained himself on drink until the rescue team pulls him from the wreckage three days later, “gloriously drunk.”

By nightfall on the 15th, Malta had only 11 operational Hurricanes left. The island’s new senior air controller, Group Captain Woody Woodhall, requested expert pilots from England. A group of men accordingly turned up a few days later. Among them was a ribald Canadian ace, Squadron Leader Stan Turner, Flight Lt. Laddie Lucas (a cultured Englishman and later a Member of Parliament) plus an affable Channel Islander, Flying Officer Raoul Daddo-Langlois (whose nickname was “Daddy-Longlegs”). But they were initially powerless to change matters. Fast running out of aircraft, the RAF was on the verge of collapse.

On 21 February, ten more pilots arrived on a Sunderland from Gibraltar. Among them was Squadron Leader Ron Chaffe who was set to take over 185 Squadron, Flight Lt. Keith Lawrence, an experienced, solemn-faced New Zealander who had two confirmed Me109 kills and Flight Lt. William “Bud” Connell, a Canadian. The others included, Flying Officers George Buchanan from Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), Ronald “Ron” West and Robert McNair, a Canadian, Pilot Officer Richard “Sandy” McHan, a volunteer from one of the American “Eagle” Squadrons in England, and an Australian, Sgt. Gordon Tweedale.

Chaffe, 27, was a friendly man, with a large, balding pate and an easy smile. His career in the Royal Air Force was remarkable in that he had joined the RAF Voluntary Reserve as a common airman in January 1939 and had since worked his up in the ranks. Within a year of his enlistment, he had become a full trained pilot and a member of a combat squadron in Scotland, even though the squadron (No 245) saw little action during the Battle of Britain. Now, he was on Malta, the ultimate battleground for fighter pilots.

Flying Officer Robert “Buck” McNair, 23 years-old, had come recommended by Stanley Turner, who had known him in England while leading the Royal Canadian Air Force’s No 411 Squadron. That unit had been untested, undisciplined — and as events would prove, ineffective. A large number of aircraft and their pilots had been lost in accidents prompting the squadron diarist to write: “Our motto Inimicus Inimico (‘Hostile to an enemy’) — should more aptly be read ‘Hostile to Ourselves’.” By Mid-December 1941, when McNair had the chance to transfer to another unit overseas, his paltry score of one confirmed victory and two shared still constituted nearly half of the squadron’s overall tally.

McNair, although thin and slender, was the type of man who stood out in the room, a born leader of men, immensely self-confident and capable of inspiring others. On one occasion while in a line of men being decorated by King George VI, he was asked how he was feeling. “Just fine, sir,” he would tell the King. “How’s the Queen?”

Although only a high school graduate, he had good grades and was employed as a radio operator for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Natural Resources. When the war broke out, he successfully joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, graduating as a fighter pilot in March 1941.

The other “Buck” in the group was George “Buck” Buchanan, who at 30-years-old was a veritable “elder” among the young men. He also answered to the nickname “Zulu” owing to his birthplace, South Africa. An account suggested that Buchanan was an ex-policeman but that he was also an employee of the North Rhodesian timber industry. He is one of the influx’s most experienced pilots, having 262 hours of operational flying under his belt, although he has just one shared victory (a biplane Henschel Hs123 spotter plane) to his credit. His grading classified him a pilot of “average” ability. He was thought to be a plodder but the sort of stable pilot which makes up the bulk of any squadron. Of the other men, Flying Officer Ron West was a rookie, as was Gordon Tweedale, an Australian who is attached to 126 Squadron.

The new arrivals, like previous batches, were given a rude awakening when the Sunderland they had just arrived in, was strafed by an Me109s as it prepared for departure. Gunfire peppered the Sunderland’s wing and tail. The great seaplane keeled over, a total wreck. It sank two days later. The aircraft had been due to fly out several tour-expired pilots who were forced to wait for another Sunderland from Gibraltar. Meantime at Luqa, ground crews were in mourning for a valuable steamroller which had been wiped out and two fuel bowsers which had been damaged.

The next afternoon, the newly arrived Ron Chaffe was shot down on his first combat sortie while chasing a Ju88. Chaffe had committed the cardinal sin — he had failed to look over his shoulder to see the Messerschmitt behind him. Chaffe was spotted in his dinghy about five miles south of Delimara Point but no one was willing to go out and get him. The rescue launch refused to go because of Messerschmitts in the area and the Hurricanes are too busy fighting to provide cover for one of the Air-Rescue flying boats available. A proper search was made only that evening when the next senior officer in No 185, Flight Lt. Rhys Martin Lloyd (no relation to Hugh Lloyd), led a flight of four Hurricanes out to sea. The flight saw nothing in the gathering gloom.

Rhys Lloyd tried again after breakfast the following morning with nine Hurricanes and a Maryland in tow. Messerschmitts bounced them as they climbed, scattering the neat formation into a disorderly tangle. Just then, someone called a warning that two Ju88s and four Me109s were approaching from the southeast. Sgt. Garth Horricks fired on one of the Ju88s and saw a flurry of strikes on the German bomber. A moment later, an Me109 attacked Horricks, forcing him to break off.

Horricks turned on his attacker, blasting the German fighter at close-range. The Messerschmitt screamed out of the sky in flames. Rhys Lloyd shot a second Ju88, seeing strikes along the wing roots and fuselage. The bomber’s engine began to disgorge black smoke. The Ju88 crash-landed back at Catania. Chaffe was forgotten in the midst of all this. The search mission returned to base when the fighting petered out. When it refueled and went out again — it came up against more Messerschmitts from a following raid. A Ju88 plummeted towards the earth, its tail lopped off by anti-aircraft fire. One RAF pilot, Sonny Ormrod, observed several padres of a local church “on a neighboring roof taking an unholy delight in watching enemy airmen crashing to their deaths.”

A rescue launch was dispatched to collect airmen in the water. They found two Germans seriously injured and the body of a third. There was no sign of Chaffe or his dinghy. The Hurricanes suspended their search when more Me109s attacked. Out of frustration and anger, Sgt. Tony Boyd of 242 Squadron raked a Messerschmitt flown by Corporal Otto Butschek, knocking it into the sea while Sgt. Jock Gardiner of 126 Squadron damaged another Me109. Butschek bailed out but perished in the sea. This was a foreshadowing of Chaffe’s fate. No trace of him was ever found. His death turned his wife, Betty, into a premature widow and left Flight Lt. Rhys Lloyd temporarily in-command of 185 Squadron.

Meanwhile, Stan Turner had been monitoring the RAF’s situation with mounting concern. He came to the conclusion that three primary deficits were causing a majority of casualties on the island — a lack of Spitfires, the haphazard way in which a jumble of squadrons were scrambled, and poor air tactics.

Because Malta also had more pilots than planes, Turner asked Lloyd to create a pool of serviceable aircraft to be used by squadrons on alternate days. This method allowed squadron commanders the option of sending up at least two or three ready sections of aircraft, instead of having all squadrons send up scattered numbers of uncoordinated flights in piecemeal fashion.

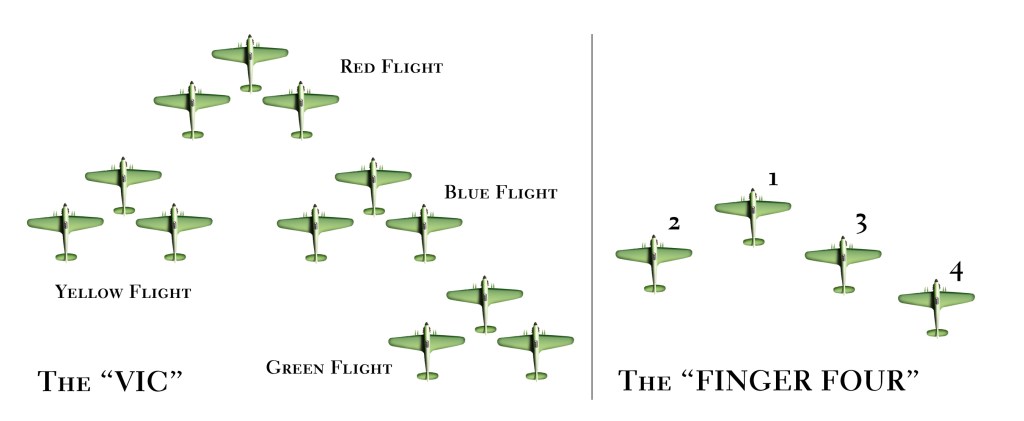

Turner also waged a war against the RAF’s “Vic” formation but struggled to convince the battle-weary veterans of 249 Squadron that his way was the right way. “Look here,” he told “Laddie” Lucas who had assumed command of 249’s A Flight, “I shall look to you to help me with changing the flying pattern here. We can’t have any more of this goddam ‘Vic’ formations otherwise we’ll all get bumped, that’s for sure. I want you to learn this line-abreast stuff with me. And quickly.”

He began to trace on a dusty floor with his foot to show the merits of the “Finger four” flight formation and how it allowed each pilot to cover the tails of the others in the flight. “This way,” he said, “A couple of guys will never get bounced: attacked maybe, yes — but never surprised, no kidding.”

The third deficiency was rooted at Lascaris, over which he had no control. For one, he disagreed with existing practices vectoring Hurricanes straight into incoming enemy aircraft. Instead, he argued that aircraft should climb southwards, away from the raiders speeding in from the north, so that they had more time and space to freely gain altitude without having to mix it in with incoming enemy fighters. He also had an issue with carelessness among fighter controllers — a conclusion forged in a first-hand experience in the skies over the island on February 24, when he and with his American wingman, Pilot Officer Don Tedford, were vectored by ground control to a flight of four Me109 “bandits” allegedly dead ahead.

Turner radioed that he could not see the enemy. The controller insisted that the enemy was right in front of him. He was wrong. The four bandits were behind Turner. The two radar plots have been misidentified.

The Messerschmitts, from Stab (HQ)/JG53— formidable foes — hit them hard. Gunfire smashed into Turner’s engine and a bullet grazed his helmet but it was Tedford who took the brunt of the damage. He radioed that he had been wounded and was bailing out over the sea. He never made it. His victor, Lt. Franz Schiess, recorded his 16th confirmed kill of the war.

Tedford’s death aggreived all other American pilots on the island, chief of all the Los Angelino, Howard Coffin, who abandoned his post at Takali to mount a long search of the coastline on the off-chance that Tedford had survived. Turner was also nearly killed. He was unable to bail out because his cockpit canopy had jammed. Outside, flames ate away at his Hurricane. He dived to extinguish the flames and pranged the kite on Luqa. This did not help his mood.

Fortuitous bad weather rolled in to give Malta a brief respite. A second batch of experienced pilots arrived as the RAF attempted to plug the holes. At Manoel island, battle fatigue was setting in. Simpson sent entire crews to a naval rest camp at Ghaijn Tuffieha in the northwestern part of the island. One submarine captain was so wound up, however, that he took to shooting at passing Messerschmitts with a rifle. Swift retribution materialized when the Germans strafed the rest camp.

At Manoel, there was no end to the raids. During a following raid on 27 February bombs fell on Lazaretto’s officers’ quarters, killing four men and injuring five. Among the dead were the skipper and three officers of the visiting Free Greek submarine, RHS Glaukos (Y6). The men, in the middle of a conference, had cavalierly chosen to disregard the air raid siren.

The Tenth Flotilla lost nearly all of its barracks in these raids. The bombs almost erased all the hard renovation work of the previous year — destroying Lazaretto’s sick bay, the cinema, the laundry and damaging mess decks. The roof of Simpson’s day cabin was blown to pieces, so he took to sleeping — as did some of his officers — in a large and derelict oil tank half-buried in rock. The tank had a floor space of 140 square feet. Planks are laid over patches of semi-coagulated oil but the stench of oil stuck to clothing, stubbornly following the men wherever they went. Soon the tank was an office. A chest of drawers and tables was installed. Officers became accustomed to seeing Simpson’s secretary, Miss Gomer, working diligently at her table as it were set on Fleet Street.

“I felt sure that the Axis intention was to destroy the submarines and the quarters of the crews as they were as much on Kesselring’s blacklist as the aerodromes,” Lloyd remarked later, with the benefit of hindsight.

Lloyd sent a message intended for Tedder and ultimately Sir Charles Portal, Chief of Staff of the Royal Air Force, in London: “Daylight attacks on aerodromes very serious. Little work being done owing to continuous alerts. Much minor damage to aircraft sufficient to make them unserviceable for night operations. They are repaired next day and then hit again. [Wellington] deliveries are a serious problem as they are damaged if they stay here during the day. The longer they stay, the more the damage. Have 17 Wellingtons in this category, including those damaged in landing on arrival here with further minor damage due to air action. To avoid this, the Wellingtons are passed through same night as arrival with relief crews. This is difficult with continuous intruder raids, but we can take it. Must have more fighters as soon as possible…Delay in Spitfires annoying.”

Lloyd was well aware that the island has only eight serviceable Hurricanes left by the month’s end. Abruptly, a rumor circulated on Friday, February 27, that Spitfires were enroute. Everyone was giddy with excitement but their enthusiasm died away at dusk. The old hands smiled knowingly. As always, London made promises it could not keep. But they were wrong. Spitfires were at Gibraltar, undergoing trials with experimental long-range fuel tanks, pending their transit to the island in the first week of March.

February died away with the island being witness of 235 alerts and 222 attacks. The island had been subject to 990 tons of bombs. When in January Fliegerkorps II had flown 1,741 sorties —these figures were up to 2,299 sorties in February (944 of which were fighter escort and 488 pure fighter patrols by JG53), with the Italians contributing 791 sorties.

The British noticed a pattern. Whereas in December and January, the attacks had been of the penny-packet variety, the raids had gained in numbers and intensity.

“At first the bombing was cautious,” said a British army intelligence officer on the island, Major R T Gilchrist. “Three Ju88s would come over three or four times a day, escorted by a large number of fighters. After a time…the raids increased to about eight a day and often five Ju88s were used. The targets were airfields and dispersal units and occasionally the dockyards. That the Germans still came in sections of only three to five was no longer due the weather but to Kesselring’s deliberate tactics of giving the enemy no rest. Whatever advantage this might have had, however, was dissipated by the fact that the defenses could concentrate its fire.”

The Italians made frantic plans for invasion. Lt-General Enno von Rintelen, the German army attaché to Comando Supreme, proposed employing large-scale German forces to invade at the end of Kesselring’s air offensive, while Rommel flies to Hitler’s headquarters in March to discuss future operations in North Africa and to ask that the island be seized.

Intended plan for Operation “C3/Herkules”

Phase 1 — Airborne landings with two divisions in the south of the island intended to capture Luqa, Hal Far & Kalafrana. After securing Luqa and Hal Far, German gliders to bring in additional troops and heavy equipment. Mdina and Qormi to be secured.

Phase 2 — 70,000-strong Italian forces to land at Marsaxlokk Bay with Italian armor, backed by special German unit equipped with ten captured Soviet KV tanks, plus Russian T-34s and German medium tanks. These units are to drive on Valletta.

Hitler did not see why Malta needed to be invaded at all. He stalled for time. To his naval chief, he declared: “I am a hero on land but a coward at sea.” In fact, Hitler had neither the stomach for an invasion nor the patience for a continued blockade which required that large naval and air forces be retained on Sicily. He decreed that the invasion, codenamed Herkules (because it was such a Herculean task) should only take place during the next full-moon period in June, which would give him enough time to add another postponement if necessary.

He also declared that air “attacks alone would prevent the enemy from building Malta’s offensive and defensive capacity.” Kesselring extolled his men to intensify the bombing and bring the British to their knees.

While this happened, Britain was preparing to deliver the first batch of Supermarine Spitfire Mk VB fighters to Malta from the old fleet carrier, HMS Eagle. Onboard the Eagle were a hundred mechanics and 16 crated tropicalized Spitfire Mark VBs. Each “Spit” each with had a large Vokes air filter in the nose which gave the elegant Spitfires a dropping, clown-like chin and cut down on their maximum speed.

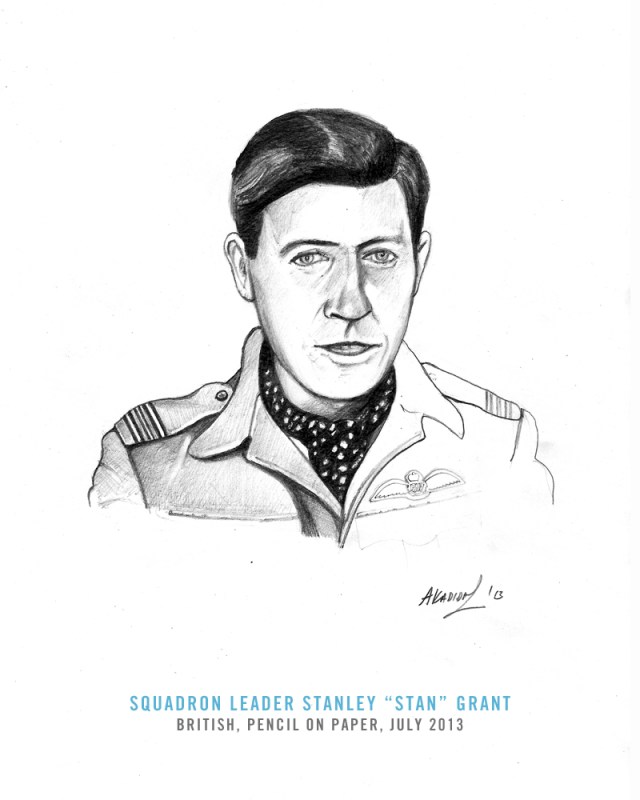

The pilot group was under the command of Squadron Leader Stanley “Stan” Grant, an Englishman possessed of the hardy, sinuous good-looks of an American Midwesterner. Grant was a 1938 graduate of the illustrious RAF College at Cranwell.

He had seen action over Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain with 65 Squadron, but had just one conclusive victory, a twin-engined Me110, to his credit.

The other pilots in the group were: Sgt. Ray Hesselyn from New Zealand, Flight Lt. Philip Heppell, Sgts. Ferraby, Ian MacCormack, John Tayleur, John “Slim” Yarra of Australia, H.J. Fox and Irving Gass, Pilot Officers Ken Murray, Bob Sim and Jim Guerin, Douglas Leggo from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and a Greek national from Rhodesia, Ioannis “Johnny” Plagis. Half of this group was destined to become aces. The most experienced among them was “Nip” Heppell who hailed from a family of fliers. His father had been an pilot in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) of the last great war and his sister was in training to become a pilot for RAF Ferry Command.

Several of the pilots were outright rookies like Sgt. Hesselyn and Johnny Plagis, the latter having failed to join the Rhodesian Air Force because he was not a citizen of that colony. Plagis was graded as “above average” during training. Since then, he had been serving with the RAF’s 266 (Rhodesia) Squadron until orders came through telling him to go to the Middle East.

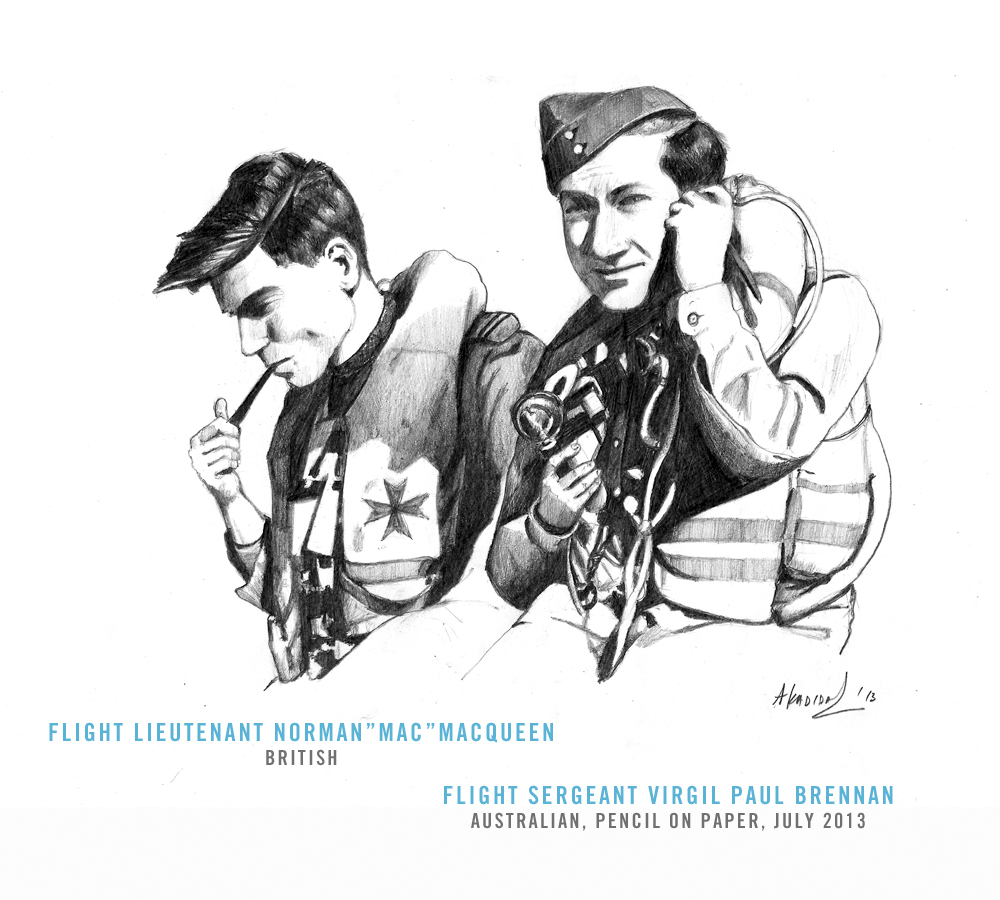

At Gibraltar, Gass and Fox were replaced by Flight Lt. Norman MacQueen and Flying Officer Norman Lee. The 22 year-old “Mac” MacQueen from Rhyl, North Wales was immensely likeable and got along with officers and NCO alike because of his humble origins — He had joined the RAF seven days after the start of the war on 10 September 1940 as an Aircraftsman (the lowest rank in the air force). His subsequent rise through the ranks was meteoric. By October 1940, he was a sergeant. A month later he was commissioned as an officer. Although he had been in action from late 1940, he had just a single damaged Me109F to his credit. He, like Plagis, had been ordered out into the Mediterranean.

Upon the carrier group’s entry at Gibraltar on 22 February, British handlers unloaded the crates at night (to conceal the operation from a German observation station over the Spanish border). Then began the work to assemble the fighters within a large warehouse. Half-finished with wings fitted and undercarriages lowered, the aircraft were loaded onto Eagle on the night of 22 February.

Four days later, on the night of February 26, the carrier sailed, accompanied by the Argus and Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Neville Syfret’s Force H. This comprised the battleships Malaya, the cruiser Hermione and nine destroyers.

When the Spitfires were readied for flight on the following day, the chief engineering officer discovered that the Spitfires’ slipper fuel tanks had been connected in such a way that fuel was being siphoned off into the airstream instead of going into the engine. The fleet turned back for Gibraltar so that a specialist could be flown in to fix the problem. Five days later, on 5 March, the British tried again. All throughout this second journey, the pilots worried that their Spitfires would not make the long journey to Malta.

The fateful moment came at 7 AM on the 7th when Eagle arrived at a point some 600 miles west of Malta. The carrier turned into the wind to allow the Spitfires to fly off. The first Spitfire “Club Run,” Operation Spotter I, had begun.

Pilots were given their orders, headings and the approximate distances to the island. Most worried that their fighters were grossly overloaded by the slipper tanks and would fail to take off from the carrier considering that she had only 667 feet of runway. “When the time came…everyone was keyed up and expectant and most of us wondered if the Spitfire would really get off the deck,” Sgt. Yarra said.

Eight Bristol Blenheims from 1442 Flight in Gibraltar, each dispatched at half-hour intervals, arrived over the carrier to lead the fighters to Malta.

“All the aircraft were lined up waiting and everyone was in their cockpits half an hour before the first Blenheim, which was to lead us, arrived,” Yarra said.

To give every pilot the fair chance of a successful takeoff, the overweight Spitfires were to wait with flaps down until the carrier rose on a wave. At this moment, the deck officer was to signal them off. The Spitfires did not have half-flaps, so a block of wood was wedged into flaps to give them a flap angle of 15 degrees. Once in flight, the flaps were to be lowered once which allow the blocks to fall away.

The slender, taut, Stanley Grant was the first off, followed by the others at 14 pre-arranged intervals. To Yarra’s consternation he discovered that his Spitfire (AB333) had a mechanical fault. He was obliged to return to Gibraltar in the Eagle.

Once airborne, the formation of Spitfires headed towards Malta. Approaching the island two hours later, they found a reception committee of Hurricanes. The Spitfires began to rapidly descend on Takali. The landing gear of Hesselyn’s Spitfire would not lower. He conducted a belly landing. When the smoke, the dust and the whirlwind of thoughts died down, the arrivals found that they were unimpressed by their new home. “Malta — the land of burnt-out Wimpeys and bowsers,” Plagis said.

The arrival of the Spitfires gave the RAF a much-needed shot in the arm. They were the first “Spits” to be based outside England. Of the three primary fighters in action over Malta, the Me109F had the advantage of speed and the MC202 had the advantage of rate of climb. The Spitfire, however, had the advantage of maneuverability, although its large Vokes air filters hobbled its rate of climb and speed. It was also heavily armored and had a strengthened main gear leg to be able to operate on Malta’s rough airfields. Even when most of the island-based Spitfires had two of their four 20mm Hispano cannons removed to reduce weight and conserve stocks of ammunition, the aircraft remained the most potently armed of the trio.

The Spitfires went into No 249 Squadron and Grant joined the unit as a supernumerary squadron commander. The infusion of pilots and aircraft resuscitated the squadron which had been languishing for lack of aircraft. Its roster now comprised 29 Spitfire-trained pilots. Most of the squadron’s Hurricane pilots were shunted to No 126 Squadron.

Four, radar-equipped and night fighting Bristol Beaufighters, which had also flown in at the tail-end of the formation, joined 1435 Flight. They gradually weaned off the unit’s Hurricanes which were ill-suited for night combat. Like the Spitfires, they were first of their kind outside Britain.

Ground crews were frantic in their attempts to get the Spitfires ready, running them through endless equipment checks and repainting their grey-green paint jobs which were more suited for Europe, with dark earth brown and middle sand or dark sea grey. While this happened, the Luftwaffe arrived in strength over the island on 9 March. The island’s serviceable Hurricanes, just 10, rose in challenge.

A Me109 fired at a Hurricane flown by Sgt. Colin Finlay. Rounds peppered the Hurricane’s elevator and blew off half of the rudder, gutting the wings and fuselage, leaving the fabric shredded with great, gaping holes through which the sinuous innards — wires, control struts and levers — could be seen.

Like a gutted, brutalized animal, the Hurricane and its pilot bolted from the scene. Finlay set the aircraft down at Takali.

Twenty minutes into noon, eighteen Ju88s from KG54 with twenty-six Me109s from III/JG53, trundled upon Luqa, Safi and Hal Far. They were met in the lawless skies by 14 Hurricanes peddling the only currency which was skill. Sgt. Archie Steele of 185 Squadron raced through the German formation, shooting at anything that crossed his path. A Me109 was fatally stricken. A Ju88 was damaged but continued flying. Another Me109 was hit but showed no outwards signs of having been damaged. A second Hurricane, flown by Sgt. Gordon Tweedale, got on the tail of a Ju88 which had just dropped its bombs. Tweedale opened up with all his guns. Eight streams of gunfire converged into a cone which ripped through the Ju88. Three Messerschmitts were drawn by the firing.

Gentle-looking, with large, quick eyes, a long chin and a faint trace of a flaxen, trimmed moustache breaking up his youthful, 24-year-old features, Tweedale was risking much by serving on Malta. He was his family’s sole breadwinner. For years since turning 15, he had supported his mother and 13-year-old brother, Graham, working lowly jobs as a clerk, as a jackeroo and as a stockman. He had eschewed a formal education to help put food on the table. But his attempts to join the Royal Air Australian Air Force had come to naught in September 1939 when his lowly educational qualifications had counted against him. He had then done what Beurling had done — obtained a private pilot’s license and improved his mathematical and navigation skills. His diligence had paid off. By July 1940, he was in flight training. Yet, his mother worried about him. After all he was a sensitive soul who despite his hard-life as a cattle-hand, played the violin, composed poetry and built model ships. But Tweedale’s mettle was hard. After all, he had volunteered to come to Malta which he described in a letter home as “the hottest place this side of hell.”

Bullets and cannon rounds tore into his Hurricane and something metal smashed into his left heel. Bleeding and in pain, Tweedale dove for the deck, his kite in bad shape with pieces falling off. He belly-landed at Takali. One Me109 followed him down, intent on killing him. The German flashed across a Hurricane being flown by Sgt. Steele who was touching down on the runway at the same time. Steele instantly opened fire. A lethal cloud of lead entered the world with the sound of ripping canvas and blazed past the Messerschmitt. The alarmed German peeled off and raced along the airfield, chased by a raking stream of anti-aircraft fire.

Despite the heroics of the Hurricane pilots, only one Ju88 had been destroyed. In return, the Luftwaffe claimed four Hurricanes shot down — when in reality none had been destroyed — although those flown by Tweedale and Pilot Officer Howard Coffin had crash-landed. Tweedale spent the next three weeks in a hospital, missing much of the carnage which would decimate his squadron in that period.

During a third raid later that day, there were no more serviceable Hurricanes to send up and so the ack-ack held the line. The anti-aircraft fire ravaged a Ju88 flown by staffelkapitän Lt. Gerhard Becker of 6/KG77. Becker and two of his crew bailed out. Flying Officer Philp “Wiggles” Wigley watched the Ju88 tear into the earth south of the airfield. Moments, later two of the bailed out German crewmen landed hundred yards away, followed by an MG13 machinegun complete with its circular, bulletproof glass screen which thudded into the ground between them. Both Germans were unconscious.

“They were taken to the Station sick quarters before they would become victims of the unfriendly intentions of local people,” Wigley said.

Incidents of Maltese atrocities upon bailed out Axis aircrews were on the rise. Howard Coffin wrote about an incident during which a German pilot had landed in his parachute only to have Maltese “swarm over him with shovels and rakes and hoes and knives. I heard one sharp cry and then the voices roared louder than ever. They cut off his head and spiked it on the gatepost of a ruined house in Mosta. I saw it when I went over days later to catch a bus to Valletta. There were three dogs sitting on their haunches and howling up at the head. I felt a bit sickened but I paused a moment to study the man’s face. Death, I suppose, strips away all corruption of thought that activates such a man. His features seemed, in death, somewhat the same as ours. It was a young face, rather woeful.”

Incredibly, despite their daily attacks on Malta, the Italians and Germans did not discover that Spitfires had arrived on the island – until 10 March. On that day, to their shock, Messerschmitt pilots found themselves besieged by seven of the new machines.

News of the Spitfires sent ripples of shock within Fliegerkorps II. The Germans rapidly reevaluated their tactics, calling for the Spitfire base at Takali to be obliterated using the maximum firepower of the Korps. Once Takali was knocked out, German bombers were to systematically reduce the island’s two remaining airfields at Hal Far and Luqa, followed by the wholesale bombing of dock installations in Grand Harbor. The attacks were scheduled to start on 20 March.

Meantime, back in England, George Beurling was posted to a Canadian fighter squadron. He found this ironic considering that the Royal Canadian Air Force had wanted nothing to do with him previously. A greater shock transpired when, on his first combat sweep over France in March, he was nearly shot down and killed by a German squadron under that erstwhile Malta ace, Lt. Joachim Münchberg (now back in Europe). Upon his return to the airfield, he discovered that Allied losses had been severe and that the skipper of the other Canadian squadron on the airfield was dead. As much as he was jarred by this first encounter with the enemy, he vowed never to be caught off-guard again.

Despite the exigencies of supplies for the battles raging in North Africa, the British Admiralty piled 30,000 tons of supplies on four cargo ships for Malta. Designated convoy MW10, the freighters bristled with anti-aircraft guns and sailed on March 20, flanked by a massive escort. Malta, meantime, was a conflagration. Valletta and the three cities area streamed black smoke as the Germans pummeled the area with rocket-powered bombs. Takali took the brunt.

A sprawl of 106 Ju88s and over 60 Me109s thundered over the island between 7 AM and 10.15 AM on 20 March. Bombs pummeled Valletta, Sliema, St. Julian’s, Hamrun, Zeitjun, Manoel Island, Grand Harbor and most important of all, Takali. The airfield was hit but several of its Spitfires and Hurricanes are airborne at the time and thus escaped immediate destruction.

Flying Officer Buck McNair shot at a Me109 as it turned. He saw pieces fall off. The Messerschmitt dove towards the sea, spewing white smoke before ending in a distant splash south of Delimara Point. McNair was exultant but nearby, Pilot Officer Doug Leggo, the Rhodesian, was in trouble.

Having spent the night drunk and with a woman, Leggo was in no shape for operations. Johnny Plagis had urged him not to fly that morning, but Leggo would have none of it. Once airborne, however, he had trouble keeping up with the rest of the flight.

All of this was noticed by a German pilot, Lt. Hermann Neuhoff, who dove from out of the sun, blasting Leggo’s Spitfire with concentrated, direct fire. The Spitfire lurched and wobbled, ejecting thick, black smoke that hung like a pall in the sky. The Spitfire went into a dive. Leggo tumbled out of doomed machine as it crossed the 22,000 ft mark and opened his chute. The island appeared like a postage stamp below him. A German fighter came roaring out the sky and either fired at the parachute or caused its collapse with its slipstream. Leggo plummeted to his death — to the horror of his squadron mates. A distraught Plagis blamed himself. “I swear to shoot down ten for Doug — I will too, if it takes me a lifetime,” he declared.

Two Ju88s bombard Valletta with PC1800 rocket-assisted bombs. One fireball was seen to smash into the now-vacated Governor’s Palace. Despite the intensity of the morning attack, casualties were unusually low — six civilians and two soldiers killed and forty-one people injured. But by far, the worst was due to come that evening when large readings appeared on Malta’s radar screens at 6.30 PM. At the fore were 63 Ju88s from nearly every bomber unit within Fliegerkorps II. They were escorted by Ju88C nightfighters and Me109s — all rumbling straight for Takali.

Not a single RAF fighter rose in challenge. The Germans roared over the airfield with impunity, shrugging off the ack-ack and blasting the landscape with heavy bombs. Fire and explosives tore through the airfield’s workshops and hangers with the bombers paying particular attention to the Mdina ramparts where Germans believe the British had underground hangers. Air reconnaissance photos had revealed a ramp at the perimeter of the airfield with a large pile of rock and earth outside. What else could it be but a subterranean hanger? The idea was not implausible. The Italians had similar underground spaces on Pantelleria.

The Ju88s dive-bombed the ramparts, dropping more PC1800 rocket-assisted bombs which were designed to penetrate 45-feet of rock. Other bombers hurled incendiary bombs onto the ramp to set the fighters within ablaze. The attack contained a measure of accuracy — except there were no underground hangers.

There was, however, little to be happy about state of Takali after the attack. Pummeled by 114 tons of bombs, the airfield was gouged and scarred and indistinguishable from a moonscape. The runway and above-ground hangers were in shambles. The anti-aircraft gunners had claimed the destruction of four Ju88s. In actuality, they had achieved the crashing of a single, bent Ju88 at Catania.

When the Germans returned on the 21st they find that not a single British fighter would take off to stop them. They took this as proof that the bombing of the “underground hangers” had been a success. Bombers from Kampfgruppen 606 and 806, I/KG54, KG77 carpet-bombed Takali, unloading 182 tons of bombs on the airfield, searing the landscape but incredibly, killing just two people and injuring seven others. This was a testament to the protectiveness of Malta’s limestone shelters.

As the bombers turned for home, eight Me110 heavy fighters from III/ZG26 materialized out of thin air and roared over Hal Far, thrashing the landscape with heavy cannon and machinegun fire. The gunfire plunged into two Hurricanes, a Spitfire and two Beauforts. Belatedly, six Hurricanes from 185 Squadron scrambled. They were led by their new skipper, Squadron Leader E.B. Mortimer-Rose.

The British were out for blood. They hammered the Me110s, claiming every single one as shot down despite the intervention of 35 Me109s. What is known for certain is that the Germans lost at least one Me110 and perhaps two more.

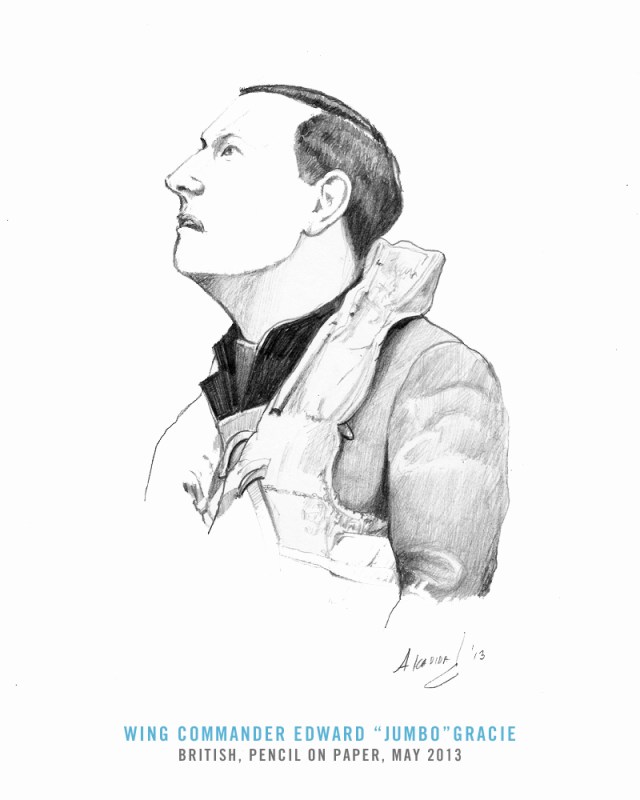

As the Me110s are being hammered, Eagle executed another club run, flying off 16 Spitfires of towards Malta. The operation was codenamed Picket I. The force was led by a redoubtable Battle of Britain ace, Squadron Leader Edward “Jumbo” Gracie DFC, a gruff and bulbous commander reputed to have joined the air force so that he could do his fighting sitting down.

He flight commander in 56 Squadron throughout the Battle of Britain shooting down four German aircraft by 1 August 1940 and claimed a further three by August 30 when he crash-landed following combat and nearly broke his neck. During Picket I, the pilots under his command were an average bunch. Several, however, were destined to make a name for themselves on the island, including Flight Lt. Hugh A.S. “Tim” Johnston, Pilot Officer Jimmy Peck (an American) and Slim Yarra, who was anxious to rejoin his mates from Spotter I.

The bad weather prevented additional Blenheim guides from rendezvousing with the carrier, forcing the launch of just the first batch of nine Spitfires. As the flight passed Pantelleria, they spotted a squadron of Italian CR42 Falcos which, to the surprise of the British, made no attempt to attack. Malta heaved into sight four hours later. The Spitfires entered the landing circuit over Takali. Flight Lt. Tim Johnston was cleared to land. Carefully scrutinizing the sky around him, Johnston dropped his wheels when he noticed two aircraft above and behind him. Deciding that they are Hurricanes, he remained in the circuit until red tracers flashed past his cockpit.

Johnston instantly retracted his landing gear and pulled the Spitfire into a hard turn so violent that he almost stalled. At that second, a pair of fast-moving aircraft zoomed overhead in a blur and disappeared. Once on the ground, a shaken Johnston was told by other pilots and ground-crews that the two machines were Me109s and that they had fired a “quick, wild burst” at him.

Slim Yarra, who had also landed, was anxious to meet his old friends from Spotter. He was aghast to learn that only two Spitfires still survived out of that original batch of 15 that had arrived just a few weeks ago. Four men whom he knew as alive, full of laughter and spirit, had been killed — Cormack, Fox, Leggo and Murray. In fact, a fifth man, Jim Guerin, would die scant minutes later.

The new Spitfires had also arrived just in time to watch a massive German raid hit Takali at 2.35 in the afternoon. Seventy Ju88s, covered by a large force of Messerschmitts, smothered the airfield and the surrounding towns of Rabat and Mosta with bombs. Miraculously, only a few aircraft are damaged, but bombing smashes the surrounding towns (excluding Mdina) and killed 64 people mostly at Mosta and Rabat.

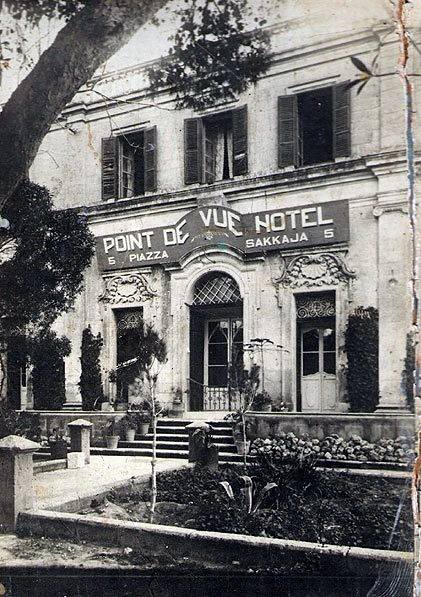

A bomb exploded outside the front door of the Point de Vue Hotel in Rabat, which had been requisitioned as a billet for officers based at Takali.

A number of RAF officers were in the lobby when an enormous, white blast obliterated their world. Four pilots were killed instantly, including Flight Lt. Cecil Baker and Pilot Officer Hollis Hallet of 126 Squadron and Flying Officer John Booth and Guerin of 249 Squadron. A 14-year old Maltese schoolboy, Leon Gamblin, who stumbled upon the scene, was horrified to see a decapitated body.

Three pilots had various degrees of wounds. Flying Officer Buck McNair was hurled nearly thirty feet upstairs by the force of the blast which forced his left arm out of its joint. When his ears stopped ringing, McNair realized what had happened.

“I heard a moan, so I put my hand gently on the bodies to feel which of them was alive,” he said. “One of them had a hole more than a foot-wide, right through the abdomen; Another’s head was split wide open into two halves, from back to front, by a piece of shrapnel. The face had expanded to twice its size. How the man was still alive I don’t know. I thought of shooting him with my revolver. As I felt for it, I heard [Flight Lt.] Bud Connell’s voice behind me: ‘Look at this mess!’”

McNair rested a hand on a wall to steady himself. His hand slithered down. The wall looked dry because it was covered with dust but was coated with blood underneath with “bits of meat stuck to it — like at the butcher’s when they’re chopping up meat and cleaning up a joint.” He turned to Connell and said: “For God’s sake, don’t come in here.” Then McNair noticed his own battledress and trousers hanging in ribbons. He helped one of the wounded to a stretcher but could not recognize the man for his mangled face. “I put a cloth over his face and then a stupid orderly took it off. It was the most horrible sight I’ve ever seen and I’ve seen chappies with heads off and gaping wounds and horrible burns…”

Another survivor, Flying Officer Ron West stood muted in shock. An ambulance pulled up in front of the ruined hotel. A doctor, seeing McNair in relative good shape, asked him to help with the bodies. “Get someone else,” McNair snapped. “I’ve seen enough.”

“As we discussed [the bombing] we began to understand the awfulness of it all. Then we started cursing the bloody Huns — it was maddening to think that all we could do was curse. We were inwardly sick, sick at heart.”

Flying Officer “Buck” McNair

Takali continued to take a pounding. By the evening of the 21st, returning German aircrews reported that it resembled the center of a “volcanic explosion.”

What a slaughter of human lives… Hospitals bombed, churches and town after town cleared out….Unless help comes soon, God save us. No food, cigarette, fuel.

Pilot Officer Howard Coffin

The bombing shattered the Valletta water reservoir situated at the edge of the airfield, flooding Takali and helping to bring some of the fires under control — but at tremendous cost. Freshwater became short in supply until the summer rains could arrive. Lloyd was appalled by the damage at Takali.

He remarked that the airfield reminded him of a World War I battlefield and feared that it would be knocked out for a week. Amid the battered airfield were the ruins of four Hurricanes, two Spitfires, a Beaufighter, a Maryland and a Wellington. Another five Spitfires, 15 Hurricanes, three Beaufighters and a Maryland had been damaged. Homes in the towns and villages surrounding the airfield had suffered terribly. At Mosta, some 35 houses have been destroyed and 31 civilians were dead and 80 injured. At Sliema, 19 homes were damaged and two people killed.

Between 20-21 March, 295 tons of bombs fell on Takali — making it the most heavily bombed airfield in the history of warfare. A bomb also hit the St. Agatha Covent at Rabat where several Maltese fascists and stalwart members of Mizzi’s nationalist party were held. Two prisoners died.

Just when it seemed that the Luftwaffe would blast the RAF from existence, the action moved away from Takali and centered on the incoming ships of convoy MW10. Just when the RAF thought it had no leg to stand on, it found that it had been given a reprieve. The convoy took their place of their suffering, taking the brunt of Axis energy and firepower, and in doing so, produced a fracas destined to enter naval lore known as the Second Battle of Sirte.

The incoming ships of the convoy MW10 had already spurred the Italian fleet into action. The Italian fleet commander, Admiral Angelo Iachino, believed he had the element of surprise. Unbeknownst to him, he had been spotted by a Malta-based submarine in the early morning hours of 22 March.

As the opposing fleets made contact that afternoon, a long-range duel developed. But a violent storm was gathering momentum. By 9 PM, massive waves threatened to swallow the combatants. At least two Italian destroyers sank in the storm before the battle petered out.

By nightfall on the 22nd, convoy MW10 was still 240 miles from Malta. The fastest ship in the convoy, Breconshire, raced ahead and was off Malta by daybreak.

The Breconshire was already a household name on Malta, having made seven previous supply runs to the island since April 1941. Instead of rushing into the harbor, she waited for the rest of the convoy to catch up. This was a mistake. Hit repeatedly by German aircraft, she was crippled while the rest of the convoy sustained losses. One freighter was sunk outright, and the remaining two were damaged. The surviving freighters berthed at Grand Harbor. They were repeatedly bombed even as Lloyd scraped together a force of 14 Spitfires and 11 Hurricanes to protect them. By 26 March, the ships were on fire and sinking.

Albert Toft, the skipper of one of the convoy ships, the SS Talabot, witnessed the bombardment of his ship from the safety of a shelter ashore. When the attack ended, he made his way way back on board to see that a bomb had gone through the electrician’s cabin and through the main deck before exploding in the engine room and starting a fire there. Another bomb had exploded near hold No. 1, where barrels of benzene have been stored. Uncontrolled, the flames crept towards Holds 3 and 4, where aviation bombs and torpedoes were kept.

Toft called on the captain of a nearby cruiser to blast a hole below the waterline to flood the engine room and extinguish the flames. The cruiser’s captain responded that he did not have the authorization to do so. The matter was forward to Vice-Admiral Leatham who sent word that he also could order the cruiser to fire on the ship. However, he gave Toft full permission to scuttle the ship.

Lt. Denis Copperwheat, an officer from a British cruiser, Penelope, volunteered to place the scuttling charges.

However, fearing that the ship’s volatile stores would go up at any moment, residents of the dock-front at Floriana began evacuating from their homes and offices. The heat from the burning ships mingled with the spring heat. At sunset, the sky over Floriana turned a dark, uneasy red.

All the surrounding areas in the Grand Harbor assume a reddish incandescence: the skies are red, the sea is red; red prevails everywhere – such a scene has never been witnessed before… Floriana looks like a furnace.

Local resident

As Toft and his crew engaged in a last minute search of their quarters to save personal belongings and artifacts, the fire reached Hold No. 1. At that moment, a gang of sailors appeared with scuttling charges . Copperwheat went to work. Toft and his crew hastily disembarked. The deck was so hot that “it sputtered under the soles of my shoes,” Toft remarked. The last off the ship was the stewardess, Margit Johnsen of Ålesund, Norway. She held the ship’s cat.

Johnsen, a survivor of the sinking of MV Tudor on 19 June 1940, impressed the men on Malta with her calm — so much so that she is awarded three medals, the War Medal, the St. Olav medal with Oak Branch and the Distinguished Service Cross of Malta — and a nickname: “Malta-Margit.” A photograph would later show her slender-necked and tall, her frizzled blonde hair blowing in the wind, standing somewhat perturbed on the deck of a ship, surrounded by both austere and admiring naval men as a commodore pinned the three medals on her blouse.

After everyone was ashore, Copperwheat detonated the charges. The Talabot went up in a series of sharp, loud explosions that rang across the dockyard. As her ruined remains settled in the shallows, her crew and her naval liaison officers were reminded that just 972 out of her total cargo of 8,956 tons had been unloaded. With her gunwale showing above the waterline, she burned for the next two days, blackening the sky over Grand Harbor. Later, Copperwheat, in a diver’s suit, would cut open several holes on her side to help other divers remove several crates of munitions, including 16 torpedoes. For his work, he would win the George Cross.

An inquest later discovered that in the two days during which they were afloat at port, Maltese dockworkers, who resenting being used as expendable labor by the British, had refused to work extended hours. Only 20% of the convoy’s cargo of 25,000 tons had been unloaded. In the finger-pointing that followed, each of the island’s military leaders — Lloyd of the RAF, Leatham of the Navy and Governor Dobbie — blamed each other, shattering cooperative harmony.

To worsen matters, Spitfire deliveries came to a halt when the carrier Eagle was withdrawn for repairs, leaving Malta in the lurch. Churchill drafted an urgent letter to the American president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, asking that the large American carrier, Wasp be loaned to the Royal Navy. The US carrier’s larger hold could accommodate 50 Spitfires.

As these arrangements were being worked out, Kesselring launched the final thrust of his spring blitz on April 2, triggering massive air battles over Valletta. Worse, the RAF learned that the Italian air force was channeling new aircraft to Sicily to augment German efforts. Such was the scale of the devastation being wrought on Malta that the Admiralty considered evacuating Simpson’s 10th Submarine Flotilla to Egypt.

April began with Kesselring praising his pilots and aircrews.

“Fliegerkorps ll, Messina, has done a splendid job in planning and the execution of the attack. Temporary interruptions of the air assault against Malta are caused by switching the attacking forces to convoys — the sinking of which is an indispensable preliminary to success against the island. ln bitter battles, these convoys, except for a few ships, have been destroyed.”

Having buoyed his men to greater deeds, Kesselring decided to launch his main assault from April 2.

With Takali thought to have been knocked out, the Germans turned their attentions to Valletta in April. The bombing was deafening, roiling the earth as if threatening to topple the city into the sea. Mountains of rubble occupied every street, flanked by lines of broken buildings. April 3, Good Friday, was grim. The airfields were hit, and two fighters destroyed on the ground and on April 4, the RAF found itself in the untenable position of having no more combat-ready fighters to scramble. In the absence of the defending fighters, the Germans had a field-day.

The Free Greek submarine, Glaukos, reeling from the deaths of its officers in a bombing raid on 27 February, was preparing to sail when she was hit by bombs and sunk. Most of the crew escaped, baring two men. “Our strength is now down to six operational submarines, and also Sokol and Unbeaten beyond repair,” Simpson reported to naval command.

Fearing for the safety of his remaining submarines, he issued new orders: Move the submarines into one of the nearby creeks and employ camouflage netting to escape detection.

On 7 April, the 23,072 square-foot architectural jewel of Malta, the Royal Opera House, was obliterated, much to the shock of the islanders. “[The Opera House]…was just a heap of rubble,” said a Maltese civilian, Memè Cortis. “I could not believe it. The Royal Opera House was like Covent Garden to us.”

The attack constituted the largest German air raid against Valletta to date and as its legacy, destroyed or damaged 70% of buildings in the capital and at Floriana. The governor’s palace had been damaged again and Dobbie suggested that he and Lloyd move the remaining offices of their headquarters inland.

“Valletta is a stricken city,” wrote The Times of Malta. “All the beautiful old palaces are bombed, all the churches have been ruined, blitzed…hundreds of houses are no more…nearly all shops destroyed…the streets are impassable, stones, dust everywhere…stones are piled high on the streets, often 20 feet high.”

At least 13 Maltese civilians had been killed, including three young girls from a single family. Many RAF pilots were disgusted by the scale of the devastation, their fury outmatched only by their profound inability to do anything about it. Said one pilot, Sgt. Wood: “The fighters want to go off but were not allowed; it was pathetic watching the havoc caused. The morale of the ground-crews and pilots was terrible; no effort was being made by the authorities to do anything and the aircraft were being written off on the ground, time and time again. The pilots were keen to have a try but the people up top just sat them on the ground and let them go to pot on the ground.”

Ships at the harbor are smashed with the cruiser HMS Penelope, of Force K, being so battered that she was nicknamed “Pepperpot.” She was ordered to leave Malta on 8 April and managed to reach Gibraltar two days later.

The Spitfires were powerless to intervene, owing to their limited numbers, poor tactics by Lloyd and sheer numbers of Messerschmitts which swamped them on every occasion. When Air Marshal Arthur Tedder (chief of the RAF in the Middle East) and Sir William Monckton (acting minister of State for the Middle East), visited the island on a fact-finding tour in the latter half of the month, they were staggered to see massive numbers of German fighters and bombers prowling overhead, shooting and bombing at will. Monckton sought to address the growing feud between Dobbie and Lloyd over the destruction of convoy MW10.

Dobbie demanded that Lloyd and other senior officers be sacked. Instead, Monckton wrote to London that Dobbie needed to go. Monckton’s indictment was that Dobbie was becoming “worn out”. he aded that there were a “litany of complaints about Dobbie, including his lack of vigor, excessive concern for civilians, and too much religion — he objects to soldiers working or training on Sundays, for example.” There was also concern that Dobbie could surrender the island to the Axis.

Churchill who had long supported Dobbie was stunned. Churchill nevertheless accepted the judgment and moved to replace Dobbie with a firebrand, General Lord Gort, VC.

Meanwhile, Simpson was staggered to learn on April 14 that his best submarine crew and captain had vanished without a trace during a patrol. This was the famed HMS Upholder which had sunk three submarines, two destroyers, one armed trawler and 15 freighters while operating out of Malta. These feats had elevated her skipper, Lt-Commander David Wanklyn, to the position of Britain’s great submarine ace and had won him a Victoria Cross.

Their loss shattered the Flotilla’s morale to such a degree that not even news of the King’s award of a George Cross to the island a day later could ameliorate their spirits. The George Cross medial itself is immensely prestigious award normally reserved for humans, for acts of great courage in non-combat situations. The award of the medal to the islands, pre-dated to April 15, was a piece of propaganda brilliance.

It is a handsome medal, ranked second only to the Victoria Cross, designed by Percy Metcalf, an English artist and sculptor, with the Metcalf-staple effigy of St. George slaying the Dragon and cast out of gleaming silver with a plain, blue ribbon. By conferring the medal, London hoped to bolster morale — thus keeping the islanders in the fight on the side of the British. Even the official citation was simplicity itself.

The Governor, Malta.

To honor her brave people I award the George Cross to the Island Fortress of Malta, to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history.

(signed) George R.I.

The Maltese were elated, gratified by the realization that they have not been forgotten by distant Britain. “It is a new thing which His Majesty has done,” Dobbie said in an address to the Maltese. The 17 April edition of the Daily Telegraph recorded the uniqueness of the honor, saying that “this is the first time a decoration has been conferred by a Sovereign on a part of the British Commonwealth.”

In contrast, some dissenting Maltese cried: “We want bread, not the George Cross,” and scattered graffiti popped up across the island, reading: “Instead of the George Cross, increase the bread ration.” Equally outraged were the Italians who described the award as another “preposterous deception by the British Government. Had not our unfortunate Maltese brethren been under the heel of British domination which is being forced on them under the threat of guns and bayonets, we have no doubt as to how the Maltese would behave.”