1942. The Last Hurrah

The Germans assembled 250 bombers and 58 Messerschmitt fighter aircraft at the end of September for the coming offensive. The Italians contributed another 200 aircraft. Many units had seen action during the April Blitz, except that some had now been re-titled to give them an edge on paper. Hauptmann Rolf Siedsclag’s Kampfgruppe 606 had become the basis for a new I Gruppe (KG77) and Major Richard Linke’s Kampfgruppe 806 had become III Gruppe (KG54).

These forces give Kesselring a force of seven, neatly-formatted Ju88 bomber groups which should have given him a strength of 250 bombers in principle. In reality, he had 156 combat-ready Ju88s.

His numbers of fighter aircraft were even smaller, amounting to 58 operational Messerschmitt Me109s strung out across four Gruppen but with some of the most dangerous pilots in the theater. The most lethal among them was I Gruppe of JG53, led by an old hand who had seen combat over Russia, OberLt. Friedrich-Karl “Tutti” Müller.

Müller, affable and young was a lean-faced pilot with slicked-back brown hair and a typically Teutonic blade-like nose. Service over Russia had seen him rapidly boost his tally to 101 confirmed victories. His three squadron commanders, Lt. Hans Möller, Lt. Erich Thomas and Lt. Wolfgang Tonne, were all aces. Tonne also had 101 credited victories. Four other pilots in the group were experten, the German honorific term used to describe an expert ace.

The wing’s II Gruppe was led by Gerhard Michalski, a squat, burly German destined to become the top Luftwaffe ace of the campaign. Twenty-one out of Michalski’s 46 aerial victories to that date were scored over Malta. Michalski’s men knew their stuff. Between May and October, the gruppe had claimed the destruction of 93 RAF aircraft (all but seven of them Spitfires), for the loss of 15 pilots. Two pilots alone had claimed a third of these victories: Michalski and an NCO pilot, Oberfeldwebel Herbert Rollwage, who has 16 victories.

The third gruppe, I/JG77, was the weakest. This unit had suffered steady casualties over the island since its arrival in the summer. Its 1st Staffel (squadron), however, continued to be led by the East Prussian ace, OberLt. Siegfried Freytag, now known alternatively as the “Star of Malta” or the “Lion of Malta” because of his 16 confirmed kills over the island (a figure which was inflated) and a total of 70 so far in the war. Many of the German fighter squadron units were equipped with new tropicalized Me109G-2 Gustavs.

The fourth gruppe was I/JG27, a crack formation from North Africa which had been brought in bolster the existing units. However, the unit had become demoralized by the loss of several of its top men, including Hauptmann Hans-Joachim Marseille, a consummate practical joker known as the “Star of Africa” who had scored 158 confirmed victories.

The Germans were backed up a 200-strong force of Italian aircraft on Sicily, with three groups of Cant Z.1007bis bombers, plus three groups of Macchi MC202s and one of Reggiane Re2001 fighters — totaling about 100 fighters. As it turned out, Italian participation would be minor.

Kesselring’s primary opposition amounted to 113 operational Spitfires spread out among five RAF squadrons, with a large pool of replacement pilots on hand, who in turn, were backed up by Malta’s invaluable radar network and anti-aircraft batteries. Nearly all of the RAF-Commonwealth old guard who had fought earlier in the year were gone, either dead or rotated home, but Park still had a cadre of 15 veteran pilots.

Malta’s Most Experienced Fighter Pilots, First Week of October

| Squadron | Cadre | Squadron | Cadre |

| 126 Sqdn | F/O Ripley Jones Sgt. Nigel Park F/L Bill Rolls F/O Rod Smith F/Sgt. Arthur Varey | 249 Sqdn | P/O George Beurling F/L Eric Hetherington F/O John McElroy P/O “Willie the Kid” Williams |

| 229 Sqdn | F/Sgt. Jim Ballantyne P/O Colin Parkinson | 1435 Sqdn | F/Sgt. Ian Maclennan F/L Wally McLeod Sgt. Allan Scott |

Among them was George Beurling who was anxious to return to the fray having been bedridden for much of August and September with “Malta Dog” (a virulent dysentery endemic to the island). The first few days were initially quiet but the storm clouds broke on October 11 when a massive force of Axis fighters and bombers attacked the island.

The October Blitz

| The Luftwaffe | ||||

| Unit | Aircraft | Strength | Airbase | Commander |

| Stab/KG54 I Gruppe II Gruppe III Gruppe | Ju88A-4 Ju88A-4 Ju88A-4 Ju88A-4 | 3 27 20 21 | Catania Gerbini Gerbini Catania | OberstLt. Marienfeld Hptm. von Platen Maj. Taubert Hptm. Ibold |

| Stab/KG77 II Gruppe III Gruppe | Ju88A-4 Ju88A-4 Ju88A-4 | 3 22 23 | Comiso Catania & Comiso Gerbini | OberstLt. Schlüter Hptm. Paepcke Maj. W. Stemmler |

| II/LG1 | Ju88A-4 | N/A | Catania | Maj. Kollewe |

| II/KG100 (Part) | He111H-6 | N/A | Catania | |

| Stab/JG53 I Gruppe II Gruppe | Me109F-4 Me109F-4/G-2 Me109F-4 | 4 20 20 | Comiso San Pietro Comiso | OberstLt. Maltzahn OberLt. F-K. Müller OberLt. Michalski |

| I/JG77 | Me109G-2 | 30 | Comiso | Hptm. Heinz Bär |

| I/JG27 | Me109F-4 | 30 | Pachino | Hptm. G. Homuth |

| I/Sch.G2 | Me109F-4 Jabo | N/A | Comiso | Maj. Schenk |

| I/122 Recce Gp | Ju88D/Me109F-5 | N/A | Catania | |

| RAF Fighter Units | ||||

| Unit | Aircraft | Standard Numbers | Commander | |

| Takali Wing 229 Squadron 249 Squadron | Spitfire Mk V Spitfire Mk V | 16 16 | W/C Donaldson S/L H.C. Baker S/L Eric Woods | |

| Luqa Wing 126 Squadron 1435 Squadron | Spitfire Mk V Spitfire Mk V | 16 16 | W/C P.P. Hanks S/L B.J. Wicks S/L A.D.J. Lovell | |

| Hal Far Wing 185 Squadron | Spitfire Mk V | 16 | W/C Thompson Maj. C.J.O. Swales | |

At 7.20 AM, seven Ju88s, escorted by 25 Macchi MC202s and four Me109s appeared off the coast, making for Hal Far. Ground controllers immediately scrambled a scratch force of 19 Spitfires from No 126, 229 and 1435 Squadrons.

A Canadian pilot, Flying Officer Rod Smith, sensed a surreal element to the scramble. “As we climbed above the haze over Malta, the sky became more beautiful than I had ever seen in the Mediterranean,” he says. “It was bright blue and crystal clear with a magnificent bank of cumulus cloud far off to the northeast.” His delight faded when he spotted the leading planes of the incoming raid at 25,000 ft. “It was the most awesome sight of our lives, in large part because the whole background of cumulus presented the whole array in a single glance.”

The raiders offered the impression of being stacked on top of each other like a staircase, with the ones at the apex trailing long white streams of water vapor. The Axis juggernaut rolled on, giving no sign of having seen the incoming Spitfires and abruptly, the British fighters were among them, shooting and weaving.

Smith closed in on the bombers as streams of tracers whipped at his Spitfire from a dozen blinking spots amid the cluster of Ju88s. He aimed at the port engine of a Junkers and opened fire, his Spitfire reverberating with the thudding of its guns. Satisfaction gushed over him as strikes erupted over the bomber cowling. The Ju88’s engine burst into flames but Smith was distracted by tracers flashed past him from German fighters.

He dove right to escape, but then to the surprise of the pursuing Germans, he whipped back around to have another go at the Ju88. The Me109s hauled after him, but Smith had time for a quick burst. Six streams of gunfire converged and the Ju88 erupted into flames before going into a fatal dive. Two more Axis planes fell — both fighters — before the raiders withdrew.

A further six Ju88s escorted by 65 fighters appeared at 10 AM. Twenty Spitfires were scrambled and intercepted the raid fifteen miles north of Comino Island. The Germans penetrated the fighter screen and approached Luqa only to be attacked by 185 Squadron. The bombers appeared unprepared for this eventuality. They dumped their bombs haphazardly over the airfield before turning around. Incredibly, despite the heady combat, not a single aircraft had fallen on either side.

A third group of raiders appeared at 1.30 PM. Wing Commander Arthur Donaldson (the new leader of the Takali Wing) had been using the quiet spell after lunch to practice dive-bombing over Filfla Rock when word reached him that a swarm of enemy bombers and fighters were headed his way.

As 28 Spitfires from 185, 229, 249 and 1435 Squadron raced to reach him, Donaldson scanned the skies and saw the approaching attackers. Over 60 strong, the raiders turned towards Takali and Rabat with a small force of seven Ju88s at their core.

Eight Spitfires of 229 Squadron rendezvoused with Donaldson who immediately led them in a head-on charge against the bombers. He picked out a Ju88 and as it ballooned in front of him, he fired. The bomber erupted into flames and fell out of formation. He plummeted towards the earth with a long tail of fire. It was Donaldson’s first full victory of the war (he had several shared victories before), but he had no time to celebrate. A colossal scrap had erupted around him. Fighters chased each other all over the sky, but then an aircraft was falling, whirling, spewing smoke, fed by flames. It was a Messerschmitt, shot down by Sgt. Jimmy Ballantyne of No 229. The Germans broke off and turned for home.

If the RAF felt that it could rest easy with its first day of tentative success, it was in for a rude surprise. At 5 PM, 16 Ju88s accompanied by 17 Falco IIs from the 22nd Group, themselves escorted by 25 Macchi MC202s and Messerschmitts turned up unexpectedly. For once, their objective was remarkably well-thought out — the Ground Control Station at Salina Bay.

But the attack quickly devolved into a fiasco. Bombs fell everywhere except on target when the raiders were beset by 25 Spitfires. The Spits harried the Germans all the way back to Sicily. Nearby, Flight Lt. Bill Rolls of 126 Squadron shot down two Falco IIs but lingered to watch the pilot of the second machine bail out and come down in the sea. The Italian inflated his dinghy and waved up at Rolls who did not wave back. At that moment, a hail of gunfire riddled his Spitfire, the aircraft shuddering and skittering, as two Messerschmitts came howling from out of nowhere.

Like a river trout recoiling at the touch, Rolls jinked his Spitfire wildly and dove flat-out for the deck, losing the Germans. He nursed his aircraft back to Luqa where despite the damage to his craft, he executed a perfect, three-point landing.

The Italo-Germans lost five more fighters before they pulled out. Three of the kills were made by 185 Squadron led into the fight by Wing Commander “Tommy” Thompson. It was a credible performance by the RAF, and remarkably, its losses had been negligible. Only three Spitfires had been lost, with one claimed by OberLt. Siegfried Freytag for his 73rd victory of the war. Perhaps to give his gutted fighter squadrons a chance to rest, Kesselring sent 30 unescorted Ju88s from KG77 and 54 to mount a finale raid at 5.45 PM, hoping that the cover of the approaching night would protect the bombers. Yet, the fading light offered no camouflage against radar.

Nine Spits, including four from 1435, led by Flight Lt. “Wally” McLeod were scrambled. The Spitfires rapidly gained altitude until they were looking down on the bombers. McLeod and his flight peeled off and dove on the Germans, attracting a storm of machinegun fire. McLeod’s Spitfire shuddered as it was hit repeatedly (it was later discovered that his Spitfire had taken 20 hits), but its determined pilot stayed on target, riddling two Ju88s which crashed in flames. Behind him, another RAF pilot, the boyish Sgt. Ian Maclennan, also dove, opening fire at a third Ju88 from a hundred yards out.

Flashes of return fire from the bomber flicked past him wild and uncoordinated. Maclennan fired back and saw a flurry of strikes erupt on the fuselage of a Ju88. The aircraft caught fire and went into a screaming dive. Three parachutes bellowed open, but by now, Maclennan was already attacking another Ju88 at close range, seeing the telltale white-yellow sparks on the wing. He broke to avoid a collision, losing sight of his quarry but saw a third Ju88 near the southeast tip of the island, racing to join a formation of other bombers. Anti-aircraft gunners on the ground have also seen the bombers and unleash a concentrated barrage.

Maclennan followed the Ju88s into this hellish airspace. Shrapnel and bullets peppered his Spitfire. With a snap and clang, his engine cowling separated from the airframe and vanished. Agitated, he closed in on a bomber and fired. The finger-like tendrils of the salvo reached out and touched a wing. A fire erupted, spreading rapidly as though it was fed by fuel. The Ju88 whirled into the sea.

McLeod, meantime, was still in combat even though his battle-damaged Spitfire was barely responsive. He scored hits on a Messerschmitt and damaged a second before his thoughts turned to self-preservation. He rumbled over Takali and belly-landed on the airfield. A fifth bomber was shot down by Sgt. Tom Kebbell, and a sixth was so badly hit that when it crash-landed on Sicily, its shell-shocked pilot had to be manhandled from the cockpit, having flown the 60 miles to Sicily with his crew dead and dying all around him.

Incredibly, this carnage had barely been completed when a second wave of Ju88s, again unescorted, appeared 30 minutes later. Set upon by 229 Squadron, the Germans lost two more planes. As night set in and the last of the raiders trail off for Sicily, the Spitfire squadrons rack up their losses. Although several of their number had been shot down or badly damaged, only one pilot — Flight Sgt. D.D. MacLean — had been killed in action. It was a remarkable achievement. Setting aside his trademark animosity of the RAF, Gort sent a message to Park: “Well done. The Spitfires have produced a fine opening score.”

Park responded, in good cricket jargon: “Spitfires have won the toss and will up their hard-hitting until the match is won.” But Kesselring had no taste for quitting —not yet.

On the next day, October 12, he increased the number of escorts. At 6.20 AM, 15 Ju88s from III/KG54 and 25 fighters head for Takali and Luqa. Warned by radar, Park scrambled the Takali Wing. Eight Spitfires from 185 Squadron were the first to make contact with the attackers out at sea.

Ten Spitfires from 249 Squadron took-off to attack. The newly arrived Squadron Leader Mike Stephens, a Battle of France ace, who had joined 249 as a supernumerary Squadron Leader, joined an NCO, Sgt. Al Stead, to bring down a Ju88. Finding a Messerschmitt nearby, Stephens also shot it down before he himself became the recipient of unwanted attention from another Messerschmitt. Cut-off and alone, Stephens took an unmitigated thrashing, and in the midst of this beating, was horrified to see his engine sputter to a halt. He took to his chute and witnessed four more planes going down in flames.

Meantime, the Ju88s split into two waves and continued their attack. The second wave attacked Hal Far, blowing up a Spitfire on the ground and damaging others, but took a plastering at the hands of 126 Squadron, losing four of their number shot down with a fifth sent back to Sicily with heavy damage. Flight Lt. Bill hammered a Ju88, seeing it literally fall to pieces when he was distracted by the sight of a Spitfire going down. He broke off his attack and came up alongside the stricken machine, only to be stunned to see that the pilot was none other than his squadron leader, Bryan Wicks, a seasoned pilot with four prior victories from 1940.

Wicks appeared injured. He pushed out of the cockpit and once in freefall, pulled the ripcord to his chute. It opened properly and “after what seemed ages, Wick landed in the water.” Rolls orbited overhead, hoping to guide a rescue launch to the scene. But Wicks, who had commanded the squadron since August, was dead. He was the first and only Spitfire squadron commander to be killed in action over Malta.

A second raid appeared a little after 9 AM with seven Ju88s nestled among a close escort of Messerschmitts and Macchis. When Donaldson led eight Spitfires from 229 Squadron into the fray 30 miles north of Gozo, the sky became filled with twisting and flaming aircraft.

A Ju88 and a Macchi were shot down, even as more Spitfires from 249 Squadron arrived and tangled with the Me109Gs. The Messerschmitts, all from II/JG53, proved no easy foes and six of them set upon Flying Officer John McElroy as he pursued a Ju88.

McElroy turned on his assailants and blasted one with a direct hit. The Messerschmitt fell out of the sky and the rest scattered. As the raiders withdraw, their retreat was narrowly cut-off by 126 Squadron who flamed two Macchis and two Ju88s before the rest escaped. Bill Rolls downed both Macchis, while one of the bombers had fallen to Sgt. Nigel “Tiger” Park, a small, slight pilot from New Zealand who happened to be Keith Park’s nephew.

Fifteen miles north of Grand Harbor, meantime, 1435 Squadron was engaged in bitter struggle with Macchis protecting a force of six Ju88s. The fracas had drawn Messerschmitts from another group and a brutal, turning dogfight began. A Messerschmitt and a Spitfire fell from the sky in flames. Two parachutes blossomed in mid-air. One landed in downtown Valletta. Its British pilot, Sgt. Kebbell, stepped out from under the canopy, causing a stir. The Ju88s plowed on towards the city — only to be intercepted by a rearguard of eight Spitfires from 185 Squadron. Several Me109s, having followed the bombers in, tore into the RAF squadron. An attacking Spitfire took a volley of hits which killed its pilot, Sgt. John Vinall as scattered and haphazard firing by the rearguard damaged several Ju88s. The German bombers remained airborne and completed their mission.

A third attack at noon by eight Ju88s, 10 Macchis and 20 Me109s was met south of Sicily by the RAF, which has been tipped off by radar. The eight Spitfires of 249 Squadron and seven others from 229 Squadron led by Donaldson approach the bombers head-on.

As the bombers distended in front of them at a staggering rate, the British opened fire. Panic rippled through the bomber formation. Flight Lt. Colin Parkinson of 229, a handsome, brawny Australian who often tied a polka-dotted bandana around his neck and radiated the stereotypical ruggedness of his countrymen, sensed the terror of his quarry.

Racing head-on towards his target, he could see strikes from his shooting ripping into the Ju88 all around the cockpit. In the split-second before he pulled up to avoid a collision, he had a vision of the front gunner sprawled dead over his gun. Both engines on the Ju88 poured out smoke and the aircraft went into a spiral dive. Parkinson was prevented from seeing what happened next because three Messerschmitts jumped him. One German overshot and in this way, committed the error which would cost him his life. Parkinson opened fire, hitting the Me109’s engine and the cockpit. Like a great leaf being tossed about by the wind, the Messerschmitt rolled and rolled, up and down before it splattered into the sea in pieces.

Donaldson focused on the leading Ju88 but saw no strikes. He broke upwards and went a stall turn to come back upon a second Ju88. He fired from a range of 200 yards. The bomber’s port engine burst into flames. The aircraft fell out of formation and dived vertically into the sea. Its four-man crew dangled above in parachutes dangling as a sort of human detritus.

Four Ju88 and four Me109s fell to this first screen of Spitfires, creating a fantastic panorama of flaming aircraft and parachutes.

It was the most spectacular sight I have ever seen. The whole sky was filled with enemy aircraft in severe trouble! I… counted no less than ten parachutes descending slowly, three from the Junkers I have shot down.

Wing Commander Donaldson

Those German who survived the first wave, closed to within 40 miles of Grand Harbor where they encountered a second screen of fighters — six Spitfires from 1435 Squadron led by Wally McLeod, who personally dispatched what he believed was the Messerschmitt leader. This Me109 was seen waggling its wings. The actual leader, Gerhard Michalski of II/JG53, destroyed a Spitfire flown by Flight Sgt. W. Knox-Williams minutes later, forcing the Australian to bail out.

Two more attacks hit the island before dusk. During the last raid, at 3.30 PM, Flight Lt. Arthur “Art” Roscoe an American from Illinois and 229 Squadron, was careless enough not to watch his tail. A Messerschmitt bounced him. He felt a great thump to his right shoulder as if someone had slapped him hard. He instinctively broke right. He glanced down at his chest to see blood trickling from an exit wound on his right breast. With a start, he realized that a cannon round had gone through him. Yet, he felt no pain and the Spitfire responded to his every touch.

He pulled the throttle back and engaged the right rudder. As his fighter shed speed, the pursuing Messerschmitt raced alongside. Time began to crawl. The two opposing pilots looked at each other as they passed and time returns to its normal tempo. The Messerschmitt raced in front. Roscoe rammed the throttle lever forward for maximum speed and pressed his trigger buttons at the same time. The Messerschmitt erupted into a fiery cloud of debris. It hurtled earthwards to its doom.

Roscoe high-tailed it back to Takali but he was bounced by another Messerschmitt. His control panel appeared to blow itself to smithereens. His engine was hit and he started to loose coolant. Jinking like a madman, he gave the German the slip and crossed the Maltese coast with his airframe vibrating and his engine clanking and groaning. He flipped the aircraft on its back so as to fall out of the cockpit but nothing happened. He appeared glued to his seat. Horrified that he had lost altitude in this foolish attempt at bailing out, Roscoe was at his wit’s end at what to do. Then he realized that his engine was still ticking away. When experiencing engine troubles, Spitfire pilots were told to flog the Merlin engine, not nurse it. Roscoe now flogged it for all it was worth.

He crash-lands at Takali, on fire, tearing across the airfield “cursing, praying and hoping” all the way, until his progress was stopped by a blast pen. He was hurled from his fighter unconscious and woke up in the hospital, nearly mummified in bandages.

When both sides retired to lick their wounds, it became clear the Axis had suffered major casualties. Combating the five raids had netted the RAF 16 enemy aircraft destroyed (including 12 Ju88s and four Me109s). Several Italian fighters were damaged but none had been shot down. In addition, 13 enemy planes had been claimed as probably destroyed or damaged. All this had been managed for the loss of seven Spitfires — three to pilots of JG53. Three RAF pilots had died and one (Roscoe) was in the hospital with serious injuries.

On the following day, Tuesday the 13th, the Germans came in early at 6.35 AM. Fighter Controllers at Lascaris Bastion radioed that enemy forces comprised 15 bombers with a sizeable escort. Spitfires from 185 Squadron climbed for altitude, sensing that the day would be long and hard like the one before, and just then, eight Ju88 and 30 Me109s came into view.

The Spitfires had no time to climb above the attackers and go at them head-on, half-way between Sicily and Malta. Several Spits broke through the fighter screen and engaged the bombers, while others become quickly enmeshed among the Messerschmitts. The initial melee was confused, with haphazard firing that failed to bring down any German machines. Instead, two Spitfires were damaged in equally rushed shooting by the Gruppenkommandeur of I/JG77, a dangerous, burly ace known as Heinz Bär who nevertheless claimed both as shot down.

Eight Spitfires from 249 led by Flight Lt. Eric Hetherington intercepted the Germans three miles north of St. Paul’s Bay.

The first to see them was George Beurling. He later claimed that before he could warn the others, his radio malfunctioned. He peeled off alone and concentrated on the outermost Ju88 flown by Feldwebel Anton Wilfer of II/LG1. A two-second burst from 300 yards tore the Junkers’ starboard wing root and triggered a great trail of black, oily smoke from the wing. The Ju88 did a slow diving turn to the right and seemed to gather speed before plunging headlong into the sea. Wilfer and his crew were killed. Yet, remarkably, no one appeared to have seen it crash and Beurling would later be denied credit for its destruction.

As Beurling turned to port, he saw a Me109 closing in on him. Beurling turned around and came tearing at the German. His guns rippled with gunfire. A dull whumpf sounded as the Messerschmitt burst into flames and roared by askew. Beurling watched it hit the sea but he had problems of his own. His cockpit seat had broken from its mounting during the high-G maneuver and it was all Beurling could do to avoid being pinned to the instrument panel. Just then, the worst possible thing happened. A second Messerschmitt comes down to tangle.

Beurling pinioned his seat back by levering his legs against the rudder controls and performed a dazzling series of tight turns until he was in position to fire on the German. His machine-guns burst into life again. His cannons remained mute, being out of ammunition. The Messerschmitt splintered. The pilot bailed out. As he deployed his chute, a Spitfire came spinning past, chased by two Me109s. The Germans concluded that the Spitfire pilot had bailed out and riddled their own man with gunfire.

Despite Beurling’s hatred of the Germans, a great revulsion and rage came over him. He nearly vomited into his oxygen mask. “Watch a helpless man be murdered in his parachute…[and] if you don’t boil, brother, and hate the living guts of every Hun-damned German, even though it’s one of his own gang you’ve watched him kill, then there’s something wrong with you,” he said later.

His radio squawked back to life, and the usual cacophony from excited dogfighters came streaming through. But Beurling had no more taste for combat. In any case, he was almost out of ammunition. He went home. As he neared Takali, he called for a crash-wagon, radioing that he “had broken his seat.” This was misunderstood as him having “broken his feet,” and a full roster of medical personnel awaited him. Back on terra firma, Beurling discovered that he was the only RAF pilot in the interception to shoot down any planes, much less score a hat-trick.

Amid this failure by the squadron, four Ju88s got through to bomb Luqa. But even as one raid materialized full of bluster, ebbed and faded away, another emerged to take its place. Kesselring was well-aware of the odds his men face, especially after the Malta-based fighter squadrons had become fully-equipped with Spitfires. Privately, he had confided to Cavallero that “any German airman daily engaged in more than one risky sortie over Malta developed a state of tension defined as ‘Maltese sickness’.”

But Kesselring’s airmen continued to come and on many occasions they succeed in stellar fashion. A second raid against Luqa that mid-morning left Luqa a shambles with bombs peppering the runway and structures. A third raid that late afternoon — again pitted against Luqa, saw several Axis fighters shot down but not a single bomber. In exchange, one Spitfire was destroyed and two more damaged in crash-landings. The planes were from 185 Squadron, the longest-serving fighter unit on the island which had possibly shot its bolt in over a year of continuous operations. All of its seasoned aces had been transferred or evacuated off-island, and the squadron’s performance, while trying to make do with new arrivals, was abysmal.

On every interception over the last two days, it had failed to dent the raiders and of those raids it had intercepted, it proved incapable of bringing down a single bomber. This dry spell is partly broken when the Germans, having bombed Luqa, turned for home. A mixed force of Spitfires from 185 and 126 caught up with them near Zonqor Point. The commander, Maj. “Zulu” Swales, a South African Air Force officer, shared in the destruction of a Ju88 from II/LG1 with Flight Sgt. Arthur Varey of 126 Squadron. The “destroyed” Ju88, however, actually crash-landed at Comiso. Other pilots from 126 Squadron destroyed two fighters during the brief engagement.

A final raid later that day resulted in the destruction of one bomber and five Axis fighters by 249 Squadron. By the end of the day, the RAF understood that it has destroyed 20 enemy aircraft. Actual Axis losses were lower. The Germans too were guilty of over-claiming. The pilots of JG53, for example, claimed the destruction of nine Spitfires — all of which were incredibly confirmed, including four claimed by Ofw. Werner Stumpf.

Nevertheless, Kesselring was unhappy. Over the course of the last three days, he had suffered the loss of 16 Ju88s, two He111Hs, one Cant Z1007 and about 20 fighters. A further nine Ju88s had been written off in crashes. Sixty-eight irreplaceable bomber-men had been killed, captured or missing.

“The assault…was not the success we had hoped for,” he said. “…Our losses were too high. The surprise had not come off, and neither had our bomber attacks against their air bases. Instead, the battle had to be fought against the enemy fighters in the air and their bomb-proof shelters on the ground.”

In his postwar memoires, Kesselring claimed that he called off the blitz at this point because he was worried about an Anglo-American invasion of Tunisia (Operation Torch), but on the next day, October 14, the attackers returned to the island in strength as though nothing had changed. And nothing had.

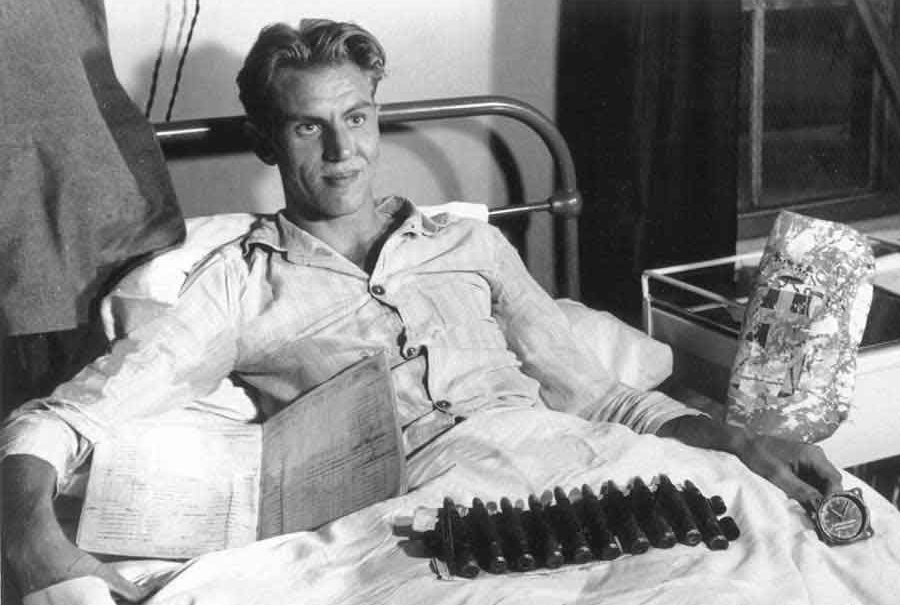

Abruptly, the RAF began to suffer casualties among its cadre. Wing Commander Donaldson of Takali lost two fingers to a cannon round on October 14 and crash-landed his Spitfire which was on fire. Minutes later, Beurling picked off a Messerschmitt from the tail of a squadron mate, saving the man’s life, but at the cost of ignoring the peril to his own tail. Savaged by a following Messerschmitt, his Spitfire went into a fatal spin. Beurling bailed out badly wounded. His war over Malta was over.

By October 16, Kesselring’s offensive was running out of steam. His bomber crews were demoralized after hitting the same targets repeatedly with little effect. Kesselring should have knocked out Malta’s radar network first, but he had forgotten this cardinal lesson from the Battle of Britain. By October 18, it was all over. Kesselring called off the offensive, admitting defeat. He had been unware that he had succeeded in nearly halving the fighter strength of the RAF. Had he maintained the blitz for another week, the RAF would have been destroyed as it nearly was, earlier in 1942.

All Kesselring can could see were the attritional losses of his own squadrons. In nine days of fighting, his aircrews had flown 2,400 sorties but had lost 34 bombers with another 13 seriously damaged. Twelve Me109 fighters had been destroyed (half of which had fallen to Beurling) as were six Italian fighters. The RAF had lost 23 Spitfires, another 20 had crash-landed and 39 were seriously damaged. Twelve Spitfires pilots had been killed and seven wounded.

The Germans began hit-and-run raids on the island in the days following the blitz but on October 20, for the first time in years, there was not a single air-raid alert.

The island’s rebirth coupled with an increasing number of attacks on Axis shipping was enough to drive Rommel to despair. Having returned to North Africa on the 25th, he was met by a barrage of bad news. Among them was the tidbit that 24 hours after his arrival, the tanker Prosperina, a veteran of previous runs, was sunk while sailing to Tobruk. Three days later, the tanker Louisiana followed her into oblivion.

Rome, finally awakening to the danger that its troops face, pressed warships and civilian vessels into service as cargo haulers. Rommel remarked that this should have been done earlier. Two days later, the British 8th Army’s counteroffensive began at El Alamein, sealing PanzerArmee Afrika’s fate. By November 2, Rommel’s army was in disarray and by the 3rd, with 6,000 of his troops killed and thousands wounded, he prepared to abandon not just Egypt but also Cyrenaica.

Hitler told him: “Stand fast, yield not a yard of room… Sieg oder Tod (victory or death,” an order which promulgated despair at Rommel’s headquarters. General Wilhelm von Thoma, the commander of the Afrika Korps, described the order as “a piece of unparalleled madness.” Rommel himself was stunned into speechlessness. With farcical timing, a telegraph arrived from Mussolini congratulating Rommel on his “successful counterattack.”

In his helplessness, Rommel raged at Kesselring under the impression that his over-optimistic reports had misled Hitler. He also castigated the Italian logistics chief, General Count Barbassetti, for Rome’s failure to send him more supplies. Malta finally crossed his mind and he bitterly remarked that the island “had the lives of many thousands of German and Italian soldiers on its conscience.” He did not, however, blame his own ambitions which had blinded him to everything but the Suez.

Operation Theseus was finished. So was Herkules – killed not only by Hitler’s pusillanimity but also by Operation Torch, the Anglo-American invasion of Algeria and Tunisia on November 8. For Malta, a light shone at the end of the tunnel after nearly two-and-a-half years of war.

In the hospital, George Beurling was harboring thought of returning to combat when Park dropped in on October 25 to drop a bombshell — Beurling was being sent home at the request of the Canadian Government which sought his help with air force recruitment and a War Bonds drive. Beurling was incredulous at the audacity of a government which had once rejected him at every turn.

His name was added to a roster of 23 wounded or tour expired pilots due to be evacuated by a Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber to Gibraltar. Among the evacuees were several friends and Wing Commander Donaldson. The Liberator, however, stalled while trying to land at Gibraltar. Beurling and 27 others survived but 12 people were killed, including two of Beurling’s closest friends. Beurling was thrown into despair. He had repeatedly saved the lives of both men over Malta.

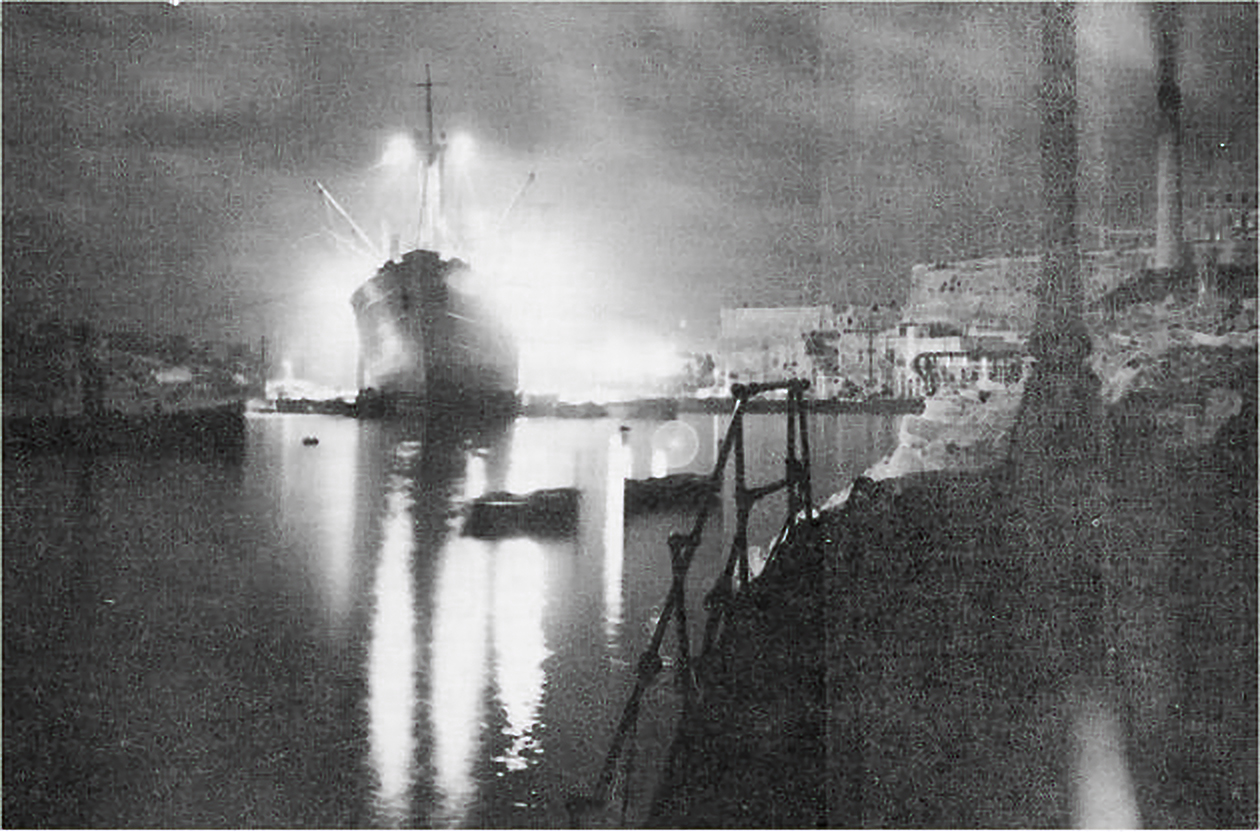

German air units begin to leave Sicily for the Russian front from November 7. Air attacks on Malta drop off sharply although the island’s woes remain unchanged. By mid-November, it was again in the throes of a supply and ammunition shortage, with only about two weeks of food left. The Admiralty sent a five-ship convoy of freighters on November 20. To everyone’s surprise, the ships arrived at Malta unscathed. When a second convoy arrived days later with 55,000 tons of supplies, it was suddenly clear to the islanders that their long siege was over. Celebrations erupted across the archipelago.

In the 29-month siege from June 1940 to November 1942, the island fortress had endured 3,343 separate air raids during which 1,581 Maltese civilians had died (one out of every 200) with another 1,846 severely wounded. Had Britain suffered the same ratio of loss, 800,000 of her civilians would have perished. The island had been subject to 16,000 tons of bombs which destroyed 15,500 buildings by 1943. Seventy-five percent of Valletta was in ruins and island waters were littered with naval wrecks.

The RAF had destroyed 863 enemy aircraft from June 1940 to 7 November 1942 and had lost 547 planes in combat. Nine hundred of its personnel had been killed, including 168 fighter pilots, the bulk of them Britons, but also 38 Canadians, 11 New Zealanders, nine Australians, six Americans, four Rhodesians and one Anglo-Indian.

The numbers prompted Tedder to remark: “I hope the lessons of Malta will not be forgotten. I trust that never again shall our unpreparedness lead our men having to face such odds or stretched so near to the limit of endurance.”

The Victory Tallies and Losses of RAF Fighter Squadrons on Malta, June 1940 to November 1942

| Squadron | 126 † | 185 | 229 | 242 | 249 | 601 | 603 | 605 | 1435 ‡ | MNFU |

| June 1940 to December 31, 1941 | ||||||||||

| Aerial kills | 40 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 24 | – | – | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| Pilots KIA | 15 | 16 | 5 | 6 | 17 | – | – | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 January to 7 November 1942 | ||||||||||

| Aerial kills | +180 | +75 | +30 | N/A | 221 | 26 | 10-20 | – | +65 | – |

| Pilots KIA | 18 | 18 | 12 | 5 | 27 | 9 | 7 | – | 8 | – |

† Includes 46 Squadron which became 126 Squadron later in 1941

‡ Includes 1435 Flight, which became a squadron in mid-1942

Far from becoming an Italian lake, the Mediterranean became an Allied thoroughfare. Large convoys began to ply the waters from mid-1943, unafraid of the threat of Axis ships, submarines or aircraft. By now, Mussolini was gone, having been ousted from power. In early 1945, as the leader of a German puppet state, the Salo Republic, he could be found telling those who still listen that he had made war on the side of the Nazis to restrain Germany.

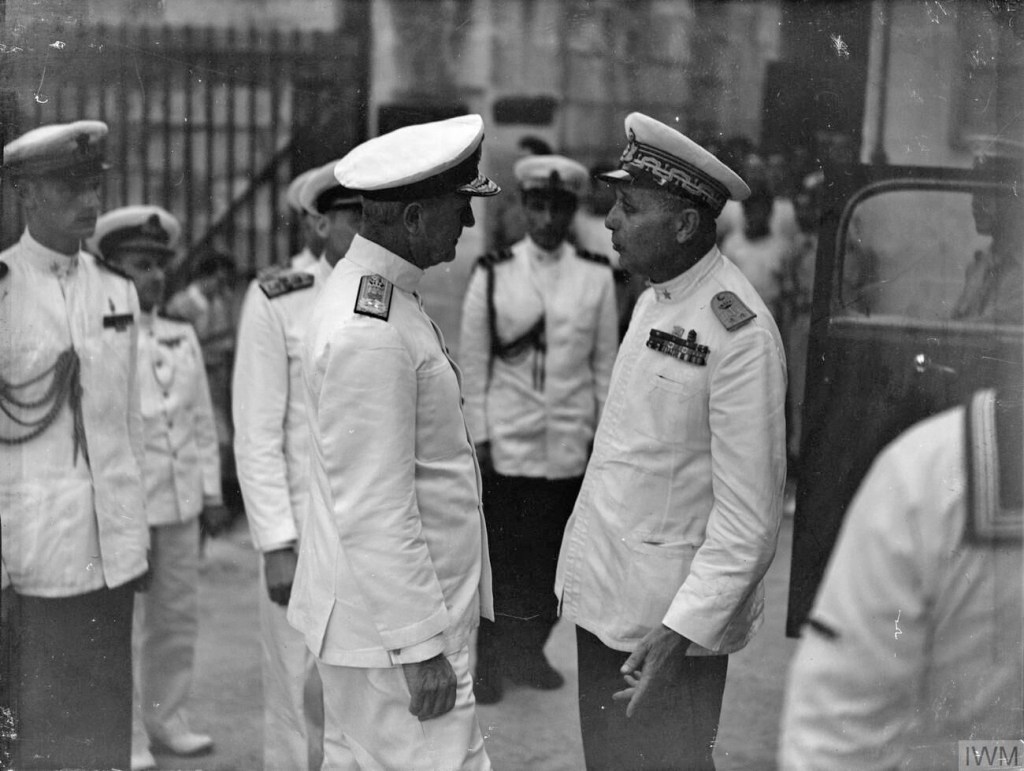

Italy signed an Armistice with the Allies in September 1943, triggering turmoil on Italy, rapture on Malta and rage in Germany which regarded the act as treachery. The Italian Navy was ordered to sail to the La Maddalena Islands in surrender. En-route, they passed the British Mediterranean Fleet sailing to occupy Taranto. Admiral Harwood was nowhere to be seen. He had been sacked in February 1943. In his place stood the old salt of the Mediterranean, Admiral Andrew Cunningham, now returned from the United States.

German Dornier Do217 bombers from Provence, each armed with revolutionary PC1400X radio-controlled gliding bombs, attacked at 3.50 PM, when the Italian fleet was within sight of La Maddalena. Two bombs smashed into the Roma which broke in half and sank with 1,300 of her crew, including Admiral Bergamini. The attack affirmed to the Italians the ruthlessness of their erstwhile Nazi allies . In utter irony, the Italian naval high command (Supermarina) radioed Malta for help.

Park declined to provide air cover as he was unable to organize an air defense force in time. In desperation, the Supermarina decided to send the fleet to Malta where it could come under the protection of the island’s air defenses. Under the command of Da Zara, the only senior Italian officer who held the respect of the British, the fleet arrived at Malta without losing additional units. The ships took up position under the guns at Grand Harbor.

“Malta is delirious with joy,” said one British expat on the island, Christina Ratcliffe. “…Church bells ring out all over the island, the streets of Valletta are festooned with flags and bunting, the crowds surge to and fro, singing happily.” For the Maltese, the war might as well be over, and in a way it was.

The Italians, however, had strict orders not to turn over the ships to the British. If boarding was unavoidable, the Italians had orders to scuttle the ships. The British did board, however, if only to inspect Italian technology and their ship-borne radar. Yet, the graciousness of the British astounded the Italians. Cunningham, following his return from Taranto, personally greeted Da Zara and spoke to him “in unexpectedly cordial terms” and when ten days later, the British complimented the Italians by asking the Regia Marina for help in the battle for Corsica, the Italians gladly obliged.

For three weeks, the Italians existed in a state riven between angst and gratitude over the hospitality of their former enemies until October 13 when the Italian state formally declared war on Germany. This prompted the Italian battlefleet to once again return to Taranto to take up station as an ally of the United Nations which it had fought so hard to defeat.

Gigantic Allied convoys begin to enter the Mediterranean following the Armistice with little fear of German attacks. Between September 1943 and December 1944, 50 convoys with an average of 69 ships entered the sea, to support not only Malta’s recovery but Allied armies fighting up the shaft of the Italian jackboot. Their sheer numbers swamped the remnants of the Kriegsmarine’s 29th Submarine Flotilla, and in turn, the Mediterranean U-boats too, become relics of the past. The last U-boat attack in the Mediterranean took place on 18 May 1944.

Reconstruction efforts on Malta began Gort asking for an initial fund of £10 million in November 1942. After the war, London would add another £20 million to the budget, largely restoring the island to its former baroque glory by 1951.

But the Maltese refused to renovate their Royal Opera House and like Picasso’s Guernica it stands as a hallowed memorial against the war. ■

Bibliography

Abulafia, David, The Great Sea, London: Penguin Books, 2014.

Allaway, Jim, Hero of the Upholder: The Story of Lieutenant Commander M.D. Wanklyn VC, London; Airlife, 1991.

Austin, Douglas, Churchill and Malta: A Special Relationship, Stroud, UK: The History Press, 2014.

“————-——“ Malta and British Strategic Policy 1925-1943, London: Frank Cass, 2004.

Barnham, Denis, Malta Spitfire Pilot, London: Grub Street, 2013.

Bekker, Cajus, The Luftwaffe War Diaries, New York: Ballantine Books, 1964.

Berg, Warren G., Historical Dictionary of Malta. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1995.

Beurling, George, Malta Spitfire: The Diary of a Spitfire Pilot, London: Grub Street, 2011.

Bierman, John & Colin Smith, Alamein, London: Penguin, 2002.

Blair, Clay, Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunters, 1939-1942, London: Orion Books, 2011.

“————,” Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunted, 1941-1945, London: Orion Books, 2011.

Boog, Horst, Werner Rahn, Reinhard Stumpf & Bernd Wegner, Germany and the Second World War, Vol VI, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001.

Bosworth, Richard J.B., Mussolini, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010.

“—————————,” Mussolini’s Italy, New York: Penguin Books, 2007.

Bradford, Ernle, The Great Siege: Malta 1565, New York: Open Road Media, 2014.

“——————,” Siege: Malta: 1940-43, London: Endeavour Press, 2013.

Bragadin, “Marc” Antonio, The Italian Navy in World War II, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1957.

Brazier, Kevin, The Complete George Cross, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2012.

Brescia, Maurizio, Mussolini’s Navy, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2012.

Brown, David, The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean, Vol 2: November 1940 to December 1941, London: Psychology Press, 2002.

Brown, J.D., Carrier Operations in World War II, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2009.

Bryant, Ben, Submarine Commander, New York: Bantam Books, 1980.

Burns, Michael, G., Bader: The Man and His Men, London: Marks & Spencer, 2003.

Busch, Harald, U-Boats at War, New York: Ballantine Books, 1955.

Caine, Philip D., Eagles of the RAF, Derby, PA: Diane Publishing, 1994.

Caldwell, Donald, JG26: The Top Guns of the Luftwaffe, Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2013.

“——————,” The JG 26 War Diary, Vol. 1, 1939-1942, London: Grub Street, 1996.

Carruthers, Bob (ed.), The Official U-Boat Commanders Handbook, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2011.

Castillo, Dennis, The Santa Marija Convoy: Faith and Endurance in Wartime Malta, 1940-1942, NY: Lexington Books, 2011.

“——————,” The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta, London: Greenwood, 2006.

Churchill, Winston, The Second World War Vol II & Vol IV, London: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1986.

Clayton, Aileen, The Enemy is Listening, New York: Ballantine, 1982.

Clayton, Tim, Sea Wolves, London: Little, Brown, 2011.

Cole, Lance, Secrets of the Spitfire, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2012.

Crosley, Michael, They Gave Me a Seafire, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2014.

Cull, Brian, 249 at War, London: Grub Street, 1997.

Cull, Brian & Frederick Galea, Hurricanes over Malta: June 1940 to April 1942, London: Grub Street, 2001.

Cunningham, Andrew, Admiral of the Fleet Viscount: A Sailor’s Odyssey, London: Hutchinson, 1951.

Douglas-Hamilton, James. The Air Battle for Malta: The Diaries of a Spitfire Pilot, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2006.

Dunning, Chris, Courage Alone: The Italian Air Force 1940-1943, Aldershot: Hikoki Publications, 1998.

Forty, George, Battle for Crete, London: Ian Allen Publishing, 2001.

Galea, Frederick, Mines over Malta, Valletta: Wise Owl, 2008.

Gibbs, Patrick, Torpedo Leader, London: Grub Street, 2009.

Granfield, Alun, Bombers over Sand and Snow, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2011.

Greentree, David, British Submarine versus Italian Torpedo Boat, London: Osprey, 2016.

Gustavsson, Hakan & Ludovico Slongo, Fiat CR42 Aces of World War II, London: Osprey, 2009.

“————————————————“ Gladiator versus CR42 Falco, London: Osprey, 2012.

Haarr, Geirr, No Room for Mistakes: British and Allied Submarine Warfare, 1939-1940, Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2015.

Higham, Robin & Stephen J. Harris (eds), Why Air Forces Fail, The University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Hart, Sidney, Submarine Upholder, Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2008.

Hastings, Max, Winston’s War: Churchill 1940–1945, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Hay, Ian, The Unconquered Isle — The Story of Malta GC, London: The Right Book Club, 1944.

Hermann, Hauptmann, The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe, London: Fonthill Media, 2012.

Hobbs, David, British Aircraft Carriers, Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2013.

Horn, Bernd (ed.), Intrepid Warriors: Perspectives on Canadian Military Leaders, Toronto: Dundrun, 2007.

Howard, Bill, What RAF Airmen took to War, New York: Shire Books, 2015.

Jacobs, Peter, Aces of the Luftwaffe, Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2014.

James, Robert Rhodes, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897-1963, New York: Chelsea House, 1974.

Jellison, Charles A., Besieged: The World War II Ordeal of Malta, 1940-1942, New Hampshire, 1985.

Johnson, David Alan, Yanks in the RAF, New York: Prometheus Books, 2015.

Johnstone, Sandy, Where No Angels Dwell, London: Jarrolds, 1969

Jones, Ben (ed.), The Fleet Air Arm in the Second World War, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2012.

Joseph, Frank, The Axis Air Forces: Flying in Support of the German Luftwaffe, Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2012.

Kavanaugh, Stephen L.W., Hitler’s Malta Option, Ann Arbor: Nimble Books, 2010.

Kesselring, Albert, The Memoires of Field Marshal Kesselring, New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016.

Knox, MacGregor, Hitler’s Italian Allies, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Kurowski, Jump into Hell: German Paratroopers in World War II, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2010.

Latimer, Jon, Alamein, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Liddell-Hart, Basil (ed.), The Rommel Papers, London: Collins, 1953

Lloyd, Hugh P. Briefed to Attack, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1949.

Lowrey, Thomas P. & John W.G. Wellham, The Attack on Taranto, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1995.

Lucas, Laddie, Five Up, Canterbury: Wingham Press, 1991.

MacDonald, Callum, The Lost Battle: Crete 1941, London: Papermac, 1995.

Macksey, Kenneth, Kesselring: The Making of the Luftwaffe, London: Frontline Books, 2012.

McCaffrey, Dan, Air Aces. The Stories of Twelve Canadians, Toronto: James Lorimer & Co., 1990.

“——————-“Hell Island: Canadian Pilots and the 1942 Battle for Malta, Toronto: James Lorimer & Co., 1998

McDonald, Paul, Malta’s Greater Siege and Adrian Warburton, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2015.

Mahlke, Helmut, Memoires of a Stuka Pilot, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2013.

Manchester, William, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Defender of the Realm 1940-45, London: Bello, 2015.

Mars, Alastair, Unbroken, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2013.

McKay, Sinclair, The Secret Listeners, London: Aurum Press, 2012.

Millet, Allan R. & Williamson Murray, Military Effectiveness, Volumes 2 & 3, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Moorehead, Alan, The Desert War, London: Aurum Press, 2013.

Morgan, Daniel & Bruce Taylor, U-Boat Attack Logs, Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2011.

Moulson, Tom, The Millionaire’s Squadron, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2014.

Neil, Tom, Scramble, London: Amberley Publishing, 2015.

Nesbit, Roy Conyers, An Expendable Squadron, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2014.

Nichols, Steve, Malta Spitfire Aces, London: Osprey Publishing, 2008.

Nicholson, Virgina, Millions Like Us, New York: Viking, 2011.

Nicholson, Arthur, Very Special Ships, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2015.

Nijboer, Donald, Cockpit: An Illustrated History of World War II Aircraft Interiors, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing, 1998.

“———————“ Spitfire V versus C202 Folgore, London: Osprey, 2014.

O’Hara, Vincent P, In Passage Perilous: Malta and the Convoy Battles of June 1942, Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2013.

“——————-“. The Struggle for the Middle Sea, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2009.

Olive, Michael & Robert Edwards, Rommel’s Desert Warriors, Mechanisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2012.

Orange, Vincent, Park: The Biography of Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, London: Grub Street, 2012.

“——————,” Tedder: Quietly in Command, NY: Routledge, 2004.

Osborne, The Watery Grave: The Life and Death of HMS Manchester, Barsnley: Frontline Books,2015.

Overy, Richard (ed.), The New York Times Complete World War II, New York: The New York Times, 2016.

Pearson, Michael, The Ohio and Malta, London: Leo Cooper, 2004.

Prien, Jochen, Jagdeschwader 53: A History of the Pik As Geschwader Vol. 1, Altgen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2004.

Ralph, Wayne, Aces, Warriors and Wingmen: The Firsthand Accounts of Canada’s Fighter Pilots in the Second World War, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

Rawlings, John D.R., Coastal Support and Special Squadrons of the RAF, London: Jane’s, 1982.

Roba, Jean-Loius & Martin Pegg, Jagdwaffe: The Mediterranean 1942-1943, London: Ian Allan, 2003.

Roberts, David D., The Totalitarian Experiment in Twentieth-Century Europe: Understanding the Poverty of Great Politics, London: Taylor & Francis, 2006.

Robertson, Stuart & Stephen Dent, The War at Sea in Photographs 1939-1945, London: Conway, 2007.

Rogers, Anthony, Battle over Malta: Aircraft Losses and Crash Sites 1940-42, Sutton Publishing Limited, 2000.

Roskill, Stephen W., The Secret Capture: U-110 and the Enigma Story, Seaforth, 2011.

Saunders, Tim, Crete: The Airborne Invasion 1941, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2008.

Savas, Theodore, Hunt and Kill: U-505 and the Battle for the Atlantic, Savas Beatie, 2004.

Schofield, Vice-Admiral B.B., Stringbag in Action, Barnsley: Pen and Sword Maritime, 2010.

Schofield, William & P.J. Carisella, Frogmen: First Battles, Boston: Branden Publishing, 1987.

Schreiber, Gerhard, Bernd Stegemann & Detlef Vogel, Germany and the Second World War, Vol III, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

Sears, Stephen W., Desert War in North Africa, American Heritage Publishing Company, 1967.

Savas, Theodore P. (ed.), Hunt and Kill: U-505 and the U-Boat War, California: Savas Beatie, 2004.

Shores, Christopher & Clive Williams, Aces High Vol. 1, London: Grub Street, 2002.

Shores, Christopher & Brian Cull with Nicola Malizia, Malta: The Spitfire Year, London: Grub Street, 1991.

Shores, Christopher, Aces High Vol. 2, London: Grub Street, 1999.

“———————,” Duel for the skies, London: Grub Street, 1998.

“———————,” The Spitfire Smiths, London: Grub Street, 2008.

Simmons, Mark, The Rebecca Code, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2012.

Simpson, George, Periscope View: A Remarkable Memoir of the 10th Submarine Flotilla at Malta 1941-1943, Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2010.

Smith, Peter C., Combat Biplanes of World War II, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2015.

“——————“, Pedestal: The Malta Convoy of August 1942, London: Kimber, 1970.

Speller, Ian (ed)., The Royal Navy and Maritime Power, New York: Routledge, 2004.

Spick, Mike, Allied Fighter Aces of World War II, London: Greenhill Books, 1997.

“————,” Luftwaffe Fighter Tactics, London: Greenhill Books, 1996.

Spooner, Tony, Warburton’s War, Manchester: Crecy Publishing, 2012.

St. John, Lauren, Rainbow’s End, London: Pheonix, 2012.

Stephenson, Charles, The Fortifications of Malta, 1530-1945, London: Osprey, 2004.

Stilwell, Alexander (ed.), The Second World War: A World In Flames, London: Osprey, 2004.

Sturtivant, Ray, The Swordfish Story, London: Cassell & Co, 2000.

Strever-Morkel, On Laughter-Silvered Wings, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2013.

Sutherland, Jon & Diane Caldwell, Images of War: Malta GC, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2009.

Tedder, Arthur, With Prejudice,London: Cassell, 1968.

Theroux, Paul, The Pillars of Hercules, New York: Penguin Books, 2011.

Thomas, Nick, Sniper of the Skies, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2015.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh (ed.), Hitler’s Table Talk, New York: Enigma Books, 2000.

Vella, Philip, Malta: Blitzed but not Beaten, Malta: Progress Press, 1985.

Von Mellenthin, Freidrich W., Panzer Battles, New York: Ballantine Books, 1971.

Walters, Derek, History of the British U-Class Submarine, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2004.

Warlimont, General Walter, Inside Hitler’s Headquarters, 1939-45, Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1991.

Whiting, Charles, Hunters from the Sky: The German Parachute Corps 1940-1945, London: Leo Cooper, 1974.

Wingate, John, The Fighting Tenth: The Tenth Submarine Flotilla and the Siege of Malta, Cornwall: Periscope Books, 2003.

Woodman, Richard, Malta Convoys, London: John Murray, 2000.

Offical Histories

Hinsley, F.H., E.E. Thomas, C.F.G. Ransom & R.C. Knight, British Intelligence in the Second World War, Vol I, London: HMSO, 1979.

Hinsley, F.H. & C.A.G. Simkins, British Intelligence in the Second World War, Vol IV, London: HMSO, 1990.

Playfair, I.S.O. et al., The Mediterranean and Middle East Vols. I, II, III & IV London: HMSO, 1954-1960.

Richards, Denis & Hilary Saunders, The Royal Air Force, 1939-1945, Vol. 2, London: HMSO, 1953

Whelan, J.A., Malta Airmen, Wellington: War History Branch, 1951.

Ark Royal: The Admiralty Account of her Achievement, London: HMSO, 1942.

East of Malta, West of Suez, London: HMSO, 1943

His Majesty’s Submarines, The Admiralty

The Air Battle of Malta, June 1940 to November 1942, London: HMSO, 1944.

The Mediterranean Fleet: Greece to Tripoli, London: HMSO, 1944.

Works of Art in Malta: Losses and Survivals in War, London: HMSO, 1946.

Other Sources

Barton, Anthony R.H., Malta Log Book (Compiled by Tony Barton)

Claude Weaver, Military Service File, Library and Archives of Canada, SWW28909

Proceedings of the RAF Historical Society, Issue 9, 1991.

The Times of Malta Archives (Also available at: https://www.timesofmalta.com/archive)

Private or self-Published

Greene, Jack, Mare Nostrum: The War in the Mediterranean, Privately published, 1990.

McAuley, Lex, Against All Odds: The Flying Career of Flight Lieutenant John Yarra, Banner Books, 2015

“—–————,”Beaufighter Nightfighter Ace Malta 1942, Banner Books, 2015

“—–————,”The Wartime Flying Career of Pilot Officer Gordon Tweedale, Banner Books, 2015.

“—–————,”The Flying Career of Flight Lieutenant Paul Brennan, Banner Books, 2015

Micaleff, Joseph, When Malta Stood Alone, Valletta, 1981.

Video

The Battle for Malta, First broadcast 7 January 2013. London: BBC

The Malta Story, directed by Brian Desmond Hurst, 1953. London: ITV Studios. 2004. DVD

Heroes of the Skies: George Beurling, First broadcast 28 September 2012, London: Channel 5.

Magazines

Flypast Magazine, “Gladiators at Malta,” Issue 2, Alfred Coldman, 1998.

Naval War College Review, Vego, Milan, “Major Convoy Operation to Malta, (Operation Pedestal),” Winter 2010, Vol 62, No 1, pgs 107-153.

Websites

Aces of the Luftwaffe, http://www.luftwaffe.cz/ (Accessed 2017)

Aces of World War II, http://acesofww2.com (Accessed 2013)

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, http://www.cwgc.org/ (Accessed 2009)

The Library and Archives of Canada, http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Pages/home.aspx (Accessed 2013)

The Luftwaffe 1933-45, http://www.ww2.dk/ (Accessed 2017)

Malta: War Diary — Story of a George Cross, http://maltagc70.wordpress.com/ (Accessed 2013)

Rhodesiana.com, “George Buchanan DFC” by Bill Musgrave, 10 May 2005. (Accessed 20 January 2012)

The U-Boat Wars 1939-1945, http://www.uboat.net/ (Accessed 2017)

World War II Unit Histories and officers, http://www.unithistories.com/ (Accessed 2017)

First-hand Accounts

Austin, Leonard, Foreman, Malta Dockyards (Aug 1939-Mar 1943)

Bamberger, Cyril, Sgt., 261/185 Sqdns, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM 27074

Broom, Ivor Gordon, P/O, 114 Sqdn, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM 10981

Cheetham, William, The Malta Convoy of August 1942 — HMS Penn, BBC People’s War, A4101625, 22 May 2005.

Hartwell, Roy William, 108 Sqdn, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM9277.

Lucas, Percy ‘Laddie,’ 249 Sqdn, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM10763.

Parry, Hugh Lawrence, F/L, 603 Sqdn, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM8985.

Rae, Jack, F/O, 249 Sqdn, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM27813

Stevens, Joseph V., Civilian

Turner, Carmela, 90th BGH (Nurse), Imperial War museum, Catalog No. IWM27092

Verity, Hugh Beresford, 252 Sqdn, Imperial War Museum, Catalog No. IWM9939

I was very interested to read your notes on Ronald Chaffe. I am currently writing a definitive history of Bristol Rugby Club, and he played one game for us in 1935-36. No official list has survived of the club’s WW2 fallen, but I knew he was one of them. However, I only knew he had died off the coast of Malta, so your notes have been of great value and will be acknowledged in the book. The only other info I have on him is that he attended Cotham School in Bristol and is listed on the war memorial there.

Mark Hoskins

Historian Bristol Rugby

Glad to be of help.

Yeah, Ron Chaffe was a very colorful character. His untimely death was the stuff of a Homeric tragedy. Completely unnecessary.

I have additional information about his time on Malta which could be of interest – although it may not be pertinent to your book.

Thank you so much. Anything else you have would be of interest. I know so little about our WW2 casualties. You may well have a couple of gems I might use.

Hi Mark,

I’m away from home, on assignment, at the moment. I’ll get you more information once I’m back.

Thank you. Absolutely no rush.

Evening, Ronald John Chaffe was my Grandad’s brother. I would love to know more about his time in Malta. I am visiting in December. Thanks, Olivia

Hi Olivia,

Thank you for your message. We can wait for Mark Hoskins to also weigh in on this, but unfortunately, Ronald Chaffee did not get to spend much time on Malta.

He arrived on Malta on 21 Feb 1942, with a group of nine pilots from Gibraltar. Assigned to command No 185 Squadron, he was thrust into his first combat action on the following afternoon.

He was chasing a Junkers Ju88 bomber when German Messerschmitt fighters shot up his Hurricane from behind. He bailed out and members of his squadron saw him in his dinghy about five miles south of Delimara Point. The British had fast rescue boats that were sent to speed out and pull downed pilots from the sea. On this occasion, however, one of the available rescue launches refused to go out because German fighters were around and the Germans were known to strafe the boats. An Air-Rescue flying boat could also not be dispatched at the tome as RAF fighters were too enmeshed in combat and could not provide cover. Therefore, a proper search for Chaffe could only be conducted that evening. The next senior officer in the squadron, Flight Lt. Rhys Martin Lloyd, led a flight of four Hurricanes on the search mission. But it was getting dark and they couldn’t see Chaffe’s dinghy.

Rhys Lloyd tried again after breakfast the following morning, with a force of nine Hurricanes and a Martin Maryland. A squadron of German fighters bounced them. Heavy fighting ensued and the search mission returned to base after combat ceased – having been unable to search for Chaffe. When a second search mission was tried a few hours later, it encountered more German fighters. But a rescue launch was finally dispatched to collect new fliers reported in the water. The launch found two seriously wounded Germans and the body of a third. There was no sign of Chaffe or his dinghy. Sadly, no trace of him was found.

I am very interesting in learning when this book will be published.

Thanks for the interest,Steven.

The book is almost complete, but I’ve been caught up in a side book project on nature for an organization – which has taken a protracted amount of time to finish.

Nevertheless, I plan to wrap up “Malta” by June and hope to move it on to the publishing stage by the end of the year.

Thanks for the information. I would be very interested in purchasing a copy if you will let me know who is selling it.

I’ll post the information on this page when it’s out. Thanks.

Very comprehensive history of the Malta disaster. My father flew Hurricanes there Nov 1941 to March 1942. Lloyd told them on parade that they (pilots) were dispensable.

A very comprehensive history of the Malta disaster. My father flew Hurricanes there from Nov 1941 – March 1942. Lloyd told them (pilots) on parade that they were dispensable. Tragic loss of life.

Thank you for your message. Yes, Lloyd was a complicated, bizarre figure who was almost theatrical in nature. What is your father’s name, if I may ask?