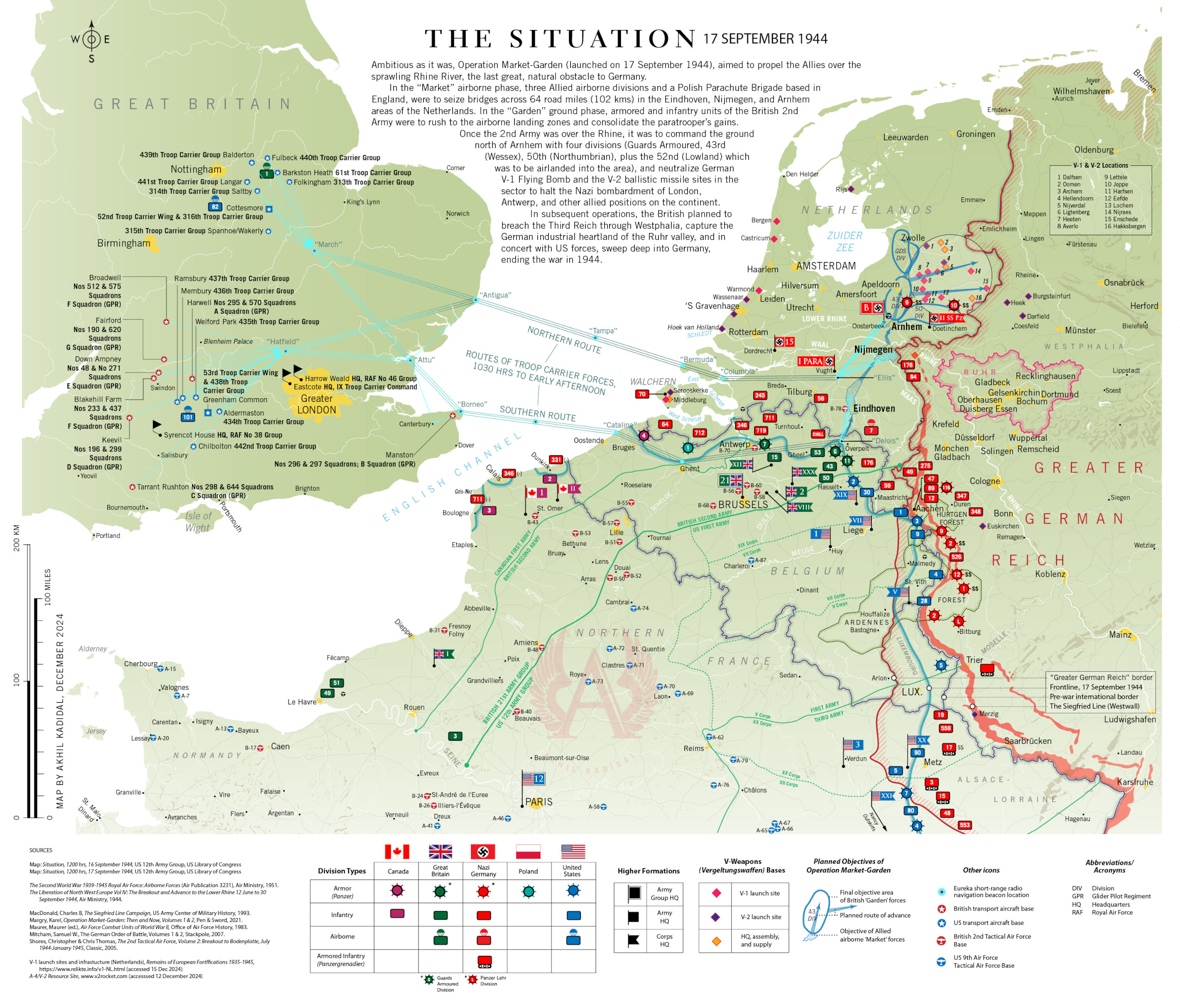

Warfare is a product of the worst of human excesses and in World War II, Operation Market-Garden was almost no different, if not for its nobility of purpose, and civility in battle. The British-US operation was an ambitious effort to hasten the end of the war by the Christmas of 1944. Instead, it went so wrong that eight decades later historians are still trying to understand what failed and why.

Conducted in the last autumn of the war, the operation aspired to propel the Allies through the eastern Netherlands and over the sprawling Rhine River (the last, great natural obstacle to Germany). From there, the Allies had a spring-board from which they could strike into Germany and attack its capital, Berlin. That dream collapsed around the destruction of the elite British 1st Airborne Division at the Dutch city of Arnhem.

That failure, occurring at the height of Allied military fortunes in the war, provided a stunning reminder of the old von Moltke1 maxim that, “no plan of operation survives first contact with the enemy” – Especially, a hastily developed plan that assumed that the Nazis were already beaten.

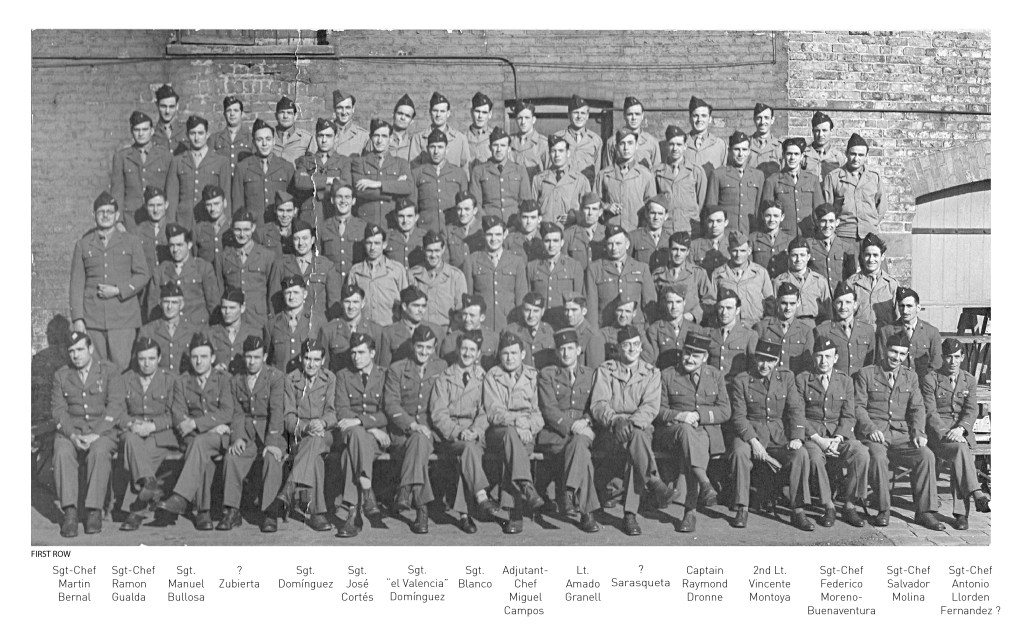

Market-Garden became better known to the general public in the postwar period. In 1946, a British film, Theirs is the Glory, filmed with 1st Airborne Division veterans in the ruins of the actual battlefield, opened to public acclaim. However, the film did little to dispel the public’s misconception that only the British Army was involved in a struggle which in reality, had also cost two US airborne divisions dearly.

A spate of memoirs by British commanders and minor histories followed.

Then came the 1974 history, A Bridge Too Far by the Irish-American journalist, Cornelius Ryan. This book gave the US airborne their dues, while creating a stunning picture of heroism, sacrifice, and stupidity. A later reprint provided this writer’s introduction to the battle, as a teen.

Despite its depth, the book did not provide all the answers. Without detailed maps on the subject, following the complexity of the battles becomes difficult, especially the convoluted battle of Arnhem. For years (until recently, I confess), I failed to grasp what had really happened and where, during obtuse battles fought in esoteric places called Ginkel, Grave, Renkum, Beek, Wolfheze, Son, and Mook.

Could these have also been the names of comic characters of another childhood? They might have been.

A 1977 film adaptation of Ryan’s book, made with a gamut of stars from Hollywood and Pinewood, reinforced some of the deficiencies of the book, including the myth that the operation failed because the 1st Airborne landed on two fully operational Waffen-SS armored divisions.

If Market-Garden has cemented itself in the public consciousness over the decades, it is because of its daring, and because of its humanistic objectives. Allied combat operations, especially in northwest Europe, were acts of liberation, fought to restore democracies and democratic institutions.2 At its essence, Market-Garden aspired to achieve this grand goal.

While the operation caused horror and tragedy, it also brought out the best in people. The heroism and sacrifice of its Allied protagonists triggered enduring gratitude from the Dutch. Surprisingly, it also elicited sentiments of honor, even decency from the Nazi combat cadre, the Waffen-SS — in spite of their moral decline which was nearly complete after five years of war and six years of nationalized racial indoctrination.

The operation’s failure, however, has caused it to be refought hundreds of times in books and films, fed by public curiosity.

Will I do some refighting of my own in the words that follow? A little. My larger objective was to use primary source statistical data (and select secondary sources) to recreate the battles through maps, infographics, and analysis. The intention is to offer a new and clear perspective of the operation.

- The Gamble

- The Politics of Warriors

- Stacked Dominoes

- All Hell Breaks Loose

- Arnhem, the Alamo

- The 8nd Airborne and a Narrow Run Thing

- The US 101st Airborne’s Frontier War

- Point of No Return

- Aftermath

- Footnotes

- Credits & Bibliography

The Gamble

Against a defeated and demoralized enemy almost any reasonable risk is justified and the success attained by the victor will ordinarily be measured in the boldness, almost foolhardiness, of his movements – Dwight D Eisenhower

By the start of September 1944, the Allies found themselves nearly the masters of northwestern Europe. The tattered remnants of Germany’s primary battle force in the region, Army Group B, were in headlong retreat after their defeat in Normandy.

The Allies were in pursuit, sweeping through northern France. Paris fell on 25 August and the Allies approached Belgium. Up to early September, one-third of British General Bernard “Monty” Montgomery’s 21st Army Group3 were clearing German forces from ports along the English Channel while the rest pushed into Belgium.

But the Allied advance was congealing. The Anglo-Americans armies were outrunning their supply lines. Nearly every port recovered from the hands of the Germans was in ruins. This limited the amount of supplies that could be landed.

Many operational ports were also in or near Normandy, which was receding into the distance as the frontlines radiated out towards Germany. The British captured the valuable deep water port at Antwerp on 4 September. But the harbor was unusable because German troops held the approaches, along the Scheldt River estuary, and especially on Walcheren island.

Compounding the problem was growing German resistance.

Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, the commander of the British Army’s XXX (30) Corps would later note (with hindsight), that the Germans were no longer in retreat by September 1944, and that Allied troops were fighting again. (Horrocks interview, World at War, “Pincers,” Episode 19)